By this time in 2019, it was obvious that 2020 was going to be a pivotal year for streaming media. Disney+ and Apple TV+ had just launched. Heavily hyped new platforms HBO Max, Peacock and, er, Quibi were preparing for their own debuts. The freshly conglomerated ViacomCBS seemed poised to overhaul its fragmented streaming strategy. (We’ll have to wait until 2021 for the result of that consolidation: a post-CBS-All-Access subscription service called Paramount+.) Established platforms Amazon Prime, Disney-owned Hulu and the monolithic Netflix would face their biggest competition yet.

What we didn’t know, of course, was that COVID-19 would hit the U.S. about 10 weeks into the year, with immediate, life-altering effects. Suddenly, the luckiest among us were stuck at home with lots of free time on our hands—time we might otherwise have spent in movie theaters or subway cars or restaurant dining rooms. So, we watched TV. Which increasingly means that we streamed it. And the abrupt shift in viewers’ attention, combined with the industry-wide changes we’d already anticipated, made for a singular year in streaming. Here, in eight items, are the conclusions I’ll take with me into 2021.

Netflix was tested—and came out stronger than ever

A few years ago, Netflix switched on its content firehose, spewing out hundreds of new originals annually and leaving no doubt that Peak TV was upon us. This approach felt excessive—not to mention unfeasibly expensive—at the time; it’s not like Amazon Prime or Hulu was ever going to challenge a production slate of such a scale. But Netflix’s focus on building a robust library makes perfect sense now, with media conglomerates snatching back decades’ worth of licensed programming for their own proprietary services. Since November 2019, the saturation strategy has been put to the test with the launches of second-generation streaming services from corporate titans with money to burn: Disney+, HBO Max, Apple TV+, NBCUniversal’s freemium offering Peacock.

Yet it was Netflix that we turned to, more than any other streamer, when COVID lockdowns confined millions of us to our homes. Even as several cornerstones of its collection—including Friends, now an HBO Max exclusive—departed for the new services to be launched by their copyright holders, Netflix achieved record-setting growth in the first quarter of the year, adding nearly 16 million subscribers. The company warned shareholders, in the spring, of a slowdown later in 2020 because such a pace wasn’t sustainable. That prediction proved accurate: Netflix gained just 2.2 million subscribers in between July and September, even falling a bit short of an internal projection of 2.5 million, in its smallest quarterly increase since 2016.

Still, with more than 195 million subscribers worldwide—and projections suggesting that it will pass the 200 million mark before 2021—as well as a near-monopoly on Nielsen’s weekly streaming top-10 list, Netflix has retained its industry-leader crown amid a year of unique challenges. By increasing and diversifying its original programming, the service has positioned itself as a viable alternative to traditional TV as a whole. In other words: its long game is working. Viewers who once shelled out for cable plus a premium channel or two might now make Netflix the center of their televisual universe, throw in a few subscriptions to Disney+ or Prime or even niche services like Criterion or Acorn, and still save money—a calculation that’s more important than ever for households squeezed by the COVID economy.

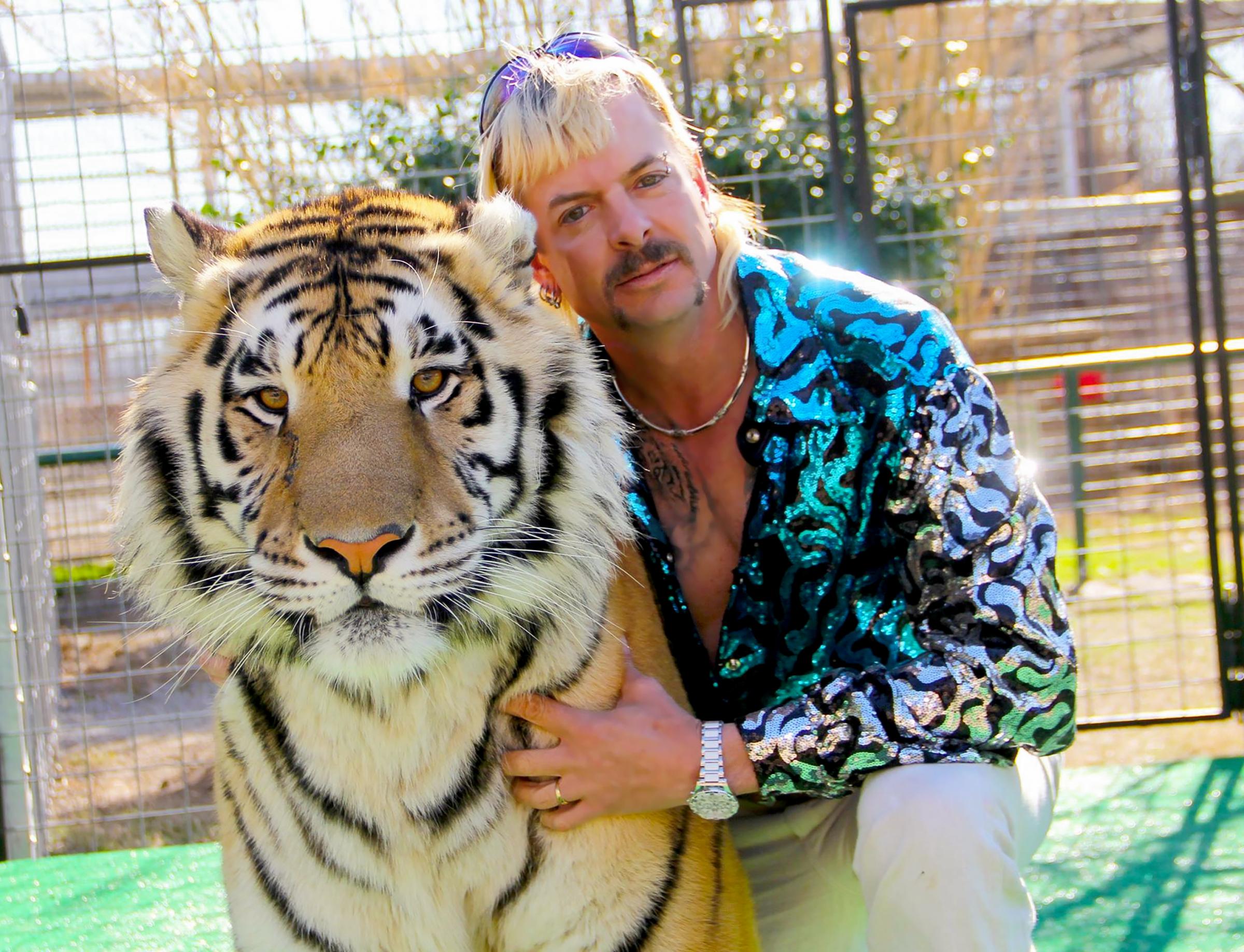

In less quantifiable (especially if you’re skeptical of the platform’s self-reported viewership stats) terms, Netflix had an unprecedented impact on the culture in a year when all entertainment was home entertainment. Slate’s Willa Paskin calls this not-entirely-positive development the “Netflix Moment,” with the service functioning as “the backdrop of everything, driving the market, setting the tone, and increasingly becoming the default place for audiences to find content.” Netflix action movies like Extraction, The Old Guard and Spenser Confidential filled the void when multiplex spectacles got pushed to 2021. Tiger King captivated news-weary viewers early in the pandemic, making Joe Exotic and Carole Baskin household names; now, Amazon is developing a series based on their story that stars Nicolas Cage. The Queen’s Gambit started a chess fad. A few years back, many critics were pronouncing the death of the monoculture. Well, it turns out the afterlife looks a lot like Netflix.

Meanwhile, Netflix’s biggest competitors—Disney and WarnerMedia—are stepping up their games for 2021

To call the ongoing struggle for the future of home entertainment the “Streaming Wars” has always been a bit misleading. It’s cable providers that have been hit hardest by the rise of streaming, not the deep-pocketed corporate monoliths like Disney, Amazon, NBCUniversal parent Comcast and WarnerMedia parent AT&T that own major streaming platforms (of course, some of those monoliths own cable providers as well). By 2019, more Americans subscribed to a streaming service than to cable, and recent studies have found that the average consumer pays for around four such subscriptions. Which suggests that the proliferation of platforms, and thus viewing options, has helped to reinforce the streaming business as a whole.

So it’s not entirely accurate to position other streaming services as a threat to Netflix. Still, it’s worth noting that none of the company’s rivals has attracted nearly as many subscribers. While Disney+ racked up 86.8 million paying customers globally in its first year, HBO Max—which only launched in May—boasts just 12.6 million activations in the U.S. These aren’t bad numbers at all; both services say they’re beating expectations. But, enviable libraries aside, neither Disney+ nor HBO Max launched with a quantity or diversity of new originals to rival, or even rattle, Netflix. That might have diminished the sense of urgency viewers (especially those who weren’t parents of Disney-obsessed kids) felt around signing up. Deadline reports, for instance, that while Max is free for HBO subscribers, only 30% had activated their accounts by early December.

Yet Disney and Warner, both companies whose theatrical release slates were thrown into chaos by the pandemic, have plans to double down on their streaming offerings in the coming year. Warner Bros. has announced that all 17 movies on its 2021 schedule—including big-budget spectacles such as The Suicide Squad and Dune, as well as prestige fare from the likes of Angelina Jolie and Lin-Manuel Miranda—will debut on HBO Max the same day they hit theaters. (This is a big, scary deal for a film industry built around blockbusters.) Considering the spike in activations and engagement that coincided with news that Wonder Woman 1984 would premiere on Max this Christmas, this could very well be a game-changer for the service.

Not to be upstaged, Disney, in a widely publicized investor call on Dec. 10, unveiled a plan to roll out 50 new Marvel, Star Wars, Pixar and Disney animated and live-action series in the next few years. If the company’s projections turn out to be correct, though of course there’s no guarantee that they will, Disney+ will surpass Netflix in subscribers sometime around 2024—and some analysts predict this could happen much sooner.

Intellectual property is more important than ever

If Disney seems more sanguine than Warner about debuting features in theaters next year, its streaming strategy and HBO Max’s overlap in one crucial way: both companies are gorging on existing intellectual property. The 50 new programs in the works for Disney+ include 10 Star Wars shows and 10 in the Marvel universe, as well as plenty of Disney and Pixar movie spin-offs. Disney’s streaming content for adults, which lives on Hulu in the U.S., already includes The Hardy Boys, Animaniacs and a handful of grownup Marvel series, among others. Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is in development.

HBO Max, meanwhile, already offers streaming originals from DC Comics, Looney Tunes and Sesame Street; more from those franchises is on the way, plus a Friends reunion special and new takes on Gossip Girl, Gremlins, Hanna-Barbera cartoons, The Boondocks. That’s in addition to HBO proper, which in many ways remains TV’s creative standard bearer. The network is now at work on Game of Thrones prequel House of the Dragon, a Parasite miniseries, an adaptation of the Last of Us video games and even—in a move that illustrates just how desperate television is to capitalize on known quantities—a True Blood reboot.

HBO isn’t the only prestige network that’s been dragged into the IP wars. Absorbed into Disney when the latter bought 21st Century Fox in 2019, FX got its own hub on Hulu this year—an addition that vastly improved Hulu’s stable of originals and significantly increased the potential audience for FX shows. Soon, FX on Hulu will house an adaptation of hit comic Y: The Last Man and a series in the Alien franchise from FX stalwart Noah Hawley. Any of these HBO or FX shows could be as great as Hawley’s Coen Brothers riff Fargo (except, probably, True Blood 2.0), but it would be hard for them to feel as fresh as era-defining auteur projects like The Sopranos or Atlanta.

The other big streamers are hardly sitting out the IP arms race, either. Netflix made hits, this past year, out of The Baby-Sitters’ Club books, an Unsolved Mysteries revival and The Haunting of Bly Manor, the second season of a homegrown classic-ghost-story-adaptation anthology. Amazon, whose long-awaited Lord of the Rings series is expected to debut in 2021, has gone big on crowd-pleasing genre fare, with adaptations ranging from superhero comic The Boys to the cult UK sci-fi series Utopia. NBCUniversal’s Peacock, which launched in July, seems to be building an identity almost solely by transforming beloved TV shows of the past into franchises. The platform finally managed to draw some attention to one of its “originals” with November’s Saved by the Bell revival, and new takes on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Law & Order, Battlestar Galactica, Punky Brewster and more are reportedly in the offing.

It’s fair to ask whether IP mania is really such a bad thing. After all, the TV space is expanding too fast for all of the ideas to be new, and adaptations of hyped “properties” aren’t necessarily more artistically ambitious than hacky but technically original concepts (compare HBO’s transcendent My Brilliant Friend to Netflix’s abysmal Space Force, then despair over how many more people watched the latter). What has worried me since Disney+ was announced is a larger trend where franchise extensions and other mega-budget tent poles from media conglomerates crowd out the small, weird cable and streaming series that have made Peak TV more than just a trash heap of monetized content. I take no pleasure in confirming that, as corporate streaming services proliferate, each with its own IP to exploit, this shift appears to be very much underway.

The pandemic accelerated cable’s inevitable demise

The writing has been on the wall for cable—expensive, inconvenient and limited in its customization options as it is—for years. But the early months of the pandemic were especially rough on that business, as everything from canceled pro sports seasons to expanded appetites for binge viewing cut into their core business. Meanwhile, the launches of HBO Max, Peacock, Disney+ and Hulu’s FX hub have provided stronger footholds in streaming for such popular cable channels as ESPN, TBS, USA, TNT and MSNBC. And when the subscription service discovery+ launches on Jan. 4, it will feature content from four of the 10 most-watched cable channels: HGTV, Food Network, TLC and Discovery Channel. “This,” an ad exec told Digiday,” is for cord cutters.”

In November, Forbes reported that cable will have lost something like 6 million subscribers in 2020 alone. Such a powerful trend would be extremely tough to reverse at this point, especially considering that major entertainment companies have mostly stopped trying to turn back the clock and shifted focus to monetizing their shows via streaming. So, who loses in the long run? Smaller channels and entertainment companies that relied on cable bundling to survive, as well as viewers who don’t have broadband internet, smart TVs or a basic understanding of streaming technology.

As cable languishes, streaming is going to get more expensive

One of the best reasons to cut the cord has always been the relative affordability of streaming. For those who choose to hang on to cable, monthly costs continue to climb, with the average bill now soaring into the triple digits. But streaming is getting more expensive with each passing year, as well. In October, Netflix announced that it would start charging $1 more per month for its standard plan and $2 more for premium options. Disney+ followed, weeks later, with news of its own $1 monthly price hike beginning in 2021.

These are pretty modest, reasonable increases. (Viewers who look to Hulu+ Live TV for a combination of streaming convenience and live access to linear broadcast and cable programs have more to complain about. They recently got word of a whopping $10/month, or 16-18%, increase.) But industry analysts expect that they’re only the beginning. After all, these price corrections represent both streaming’s new role as an alternative (rather than a supplement) to cable and the huge sums of money that leading services spend on original programming. Netflix regularly takes on debt in order to expand its offerings and become indispensable to potential lifelong subscribers. And competition between Netflix and Disney+, in particular, seems likely to result in even bigger content spends for both platforms. Sooner or later, these corporations, and the ones struggling to keep pace with them, will have to pass their skyrocketing costs on to customers.

Reality and lifestyle TV are more crucial than ever

Conventional wisdom holds that in the mid-2000s, a renaissance in scripted television beat back the scourge of reality TV. But the truth is, while AMC, FX and premium channels invested in the kind of prestige-y programming that the chattering classes love to chatter about, the cost-effective reality genre kept thriving on Bravo, TLC and the broadcast networks for whom ancient-in-TV-years franchises like The Bachelor and Survivor remain perennial hits. Lifestyle channels such as eager-to-please Food Network and particularly HGTV, for their parts, appeal to both sides of a polarized country with shows that soothe its many anxieties. So it makes sense that, in recent years, streaming services—notably Netflix—have used original reality and lifestyle programming to lure cable subscribers who care less about appointment television than about having access to a 24/7 stream of design, food, DIY and Real Housewives content. (That helps to explain why, for instance, Netflix and Amazon have each created their own Project Runway knockoff.)

These investments have paid unexpected dividends in pandemic-stricken 2020. Whether you think of this lightweight nonfiction programming as part of a relatively benign pendulum swing away from dark, dense dramas and toward “peak comfort” or as one variety of the brain-numbing audiovisual muzak that is “ambient TV,” if not a little bit of both, there’s no denying that it was everywhere this year. With so many Americans stuck at home, in their off-hours as well as during the workday, HGTV and the Food Network saw enormous ratings jumps. Wellness TV is a thing now. And audiences ate up just about every flashy nonfiction show Netflix had to offer, from beloved stalwarts (The Great British Baking Show, Queer Eye) to supremely silly debut series such as Gwyneth Paltrow’s The Goop Lab, Indian Matchmaking and Too Hot to Handle.

The trend shows no sign of letting up. Earlier this month, Disney announced that reality TV’s first family, the Kardashian-Jenners, had signed a multi-year deal to create exclusive content for Hulu and its counterparts around the world, with the first examples rolling out in 2021. Before that, discovery+ will launch with 50 originals, including spin-offs of TLC’s 90-Day Fiancé, Food Network’s Chopped, HGTV’s House Hunters and (too) much more. Honestly, I’m exhausted just thinking about it all. The only upside is that, if there’s a ceiling to reality and lifestyle content, it will likely come into view by the end of next year.

Second-generation streaming services (even the ones that aren’t Disney+) are starting to find their respective niches

OK, so cable is in a death spiral, IP rules everything around us, Warner is kicking movie theaters while they’re down, Netflix is our streaming overlord—at least until Disney+ really gets going—and the COVID-damaged marketplace is saturated with reality and lifestyle fluff. Anything positive to report on the streaming front?

Actually, yes! The best news I’ll take away from the year in streaming is that, wearying though the past 14 months of major subscription-service launches have been, at least they’re finally starting to pay off in worthwhile shows. Apple TV+ had a disappointing first few months in late 2019, as The Morning Show and other expensive originals (with the exception of the wonderfully weird Dickinson) failed to impress. But this year it’s carved out a niche with some of TV’s best new comedies—Ted Lasso, Mythic Quest, Central Park—and a fantastic slate of documentary series (Visible: Out on Television, Home) and features (Beastie Boys Story, Boys State, Fireball: Visitors From Darker Worlds). HBO Max also started out slow but has built momentum with more-playful-than-HBO originals like bubbly thriller The Flight Attendant, bruising Britcom I Hate Suzie, wild doc Class Action Park and Let Them All Talk—a Steven Soderbergh feature that sends Meryl Streep, Candice Bergen and Dianne Wiest across the ocean on the Queen Mary 2.

Fans of international TV, in particular, should be thrilled by the increased options. Along with Suzie, standouts on Max include the sharply written British comedies Stath Lets Flats and Pure, the acclaimed Spanish drama Veneno and Crunchyroll’s exuberant Japanese anime Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken! Peacock has specialized in English-language imports (many of them from the UK-based Comcast subsidiary Sky), offering brainy thriller The Capture, the racially charged alternate history epic Noughts + Crosses and more. Watching all of it would be impossible, but if ever there was a year to try, 2020 would’ve been the one.

Quibi is a cautionary tale for entertainment startups everywhere

More good news: Quibi failed. I’m not saying this to be snarky, though I’ll admit that the prospect of watching 10 minutes’ worth of a movie while waiting in line at the grocery store never appealed to me. But in an overcrowded streaming market, it’s a relief to see bad ideas flame out quickly so something better can emerge. The brainchild of DreamWorks co-founder Jeffrey Katzenberg and former Hewlett Packard CEO Meg Whitman, Quibi raised an astonishing $1.75 billion before launching in April with an enormous catalog of expensive, celebrity-packed but mostly uninspired short-form series. (It wasn’t ideal, either, to debut a product tailored to the urban commute during a pandemic.) The debacle always felt like an exercise in entrepreneurial hubris, as a feedback loop of baby boomers poured money into an idea whose many major flaws most smartphone users under 50—i.e., Quibi’s target audience—could easily have spotted. A premium mobile streaming service still seems inevitable, whether I’m excited for it or not. But the disaster that was Quibi suggests that to succeed, its founders will need to understand what viewers raised on free video platforms like Instagram, YouTube and TikTok want. That’s a valuable lesson for upstart entertainment ventures—and one that every company, new and old, in the streaming space will eventually have to absorb.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com