Creators can be cagey about the sources of their ideas, but there’s nothing mysterious about the genesis of Steve Carell and Greg Daniels’ new comedy. The development team at Netflix got wind of President Trump’s plans to create an independent branch of the military called Space Force, decided it would make a good premise for a sitcom and contacted Carell to gauge his interest. Carell, in turn, recruited Daniels, with whom he’d collaborated on one of the most successful network comedies of the 21st century: The Office. “It was really based on nothing,” Carell said in a promotional interview, “except this name that made everybody laugh.”

You can tell. Space Force, whose 10-episode first season comes to Netflix on May 29, is exactly what you’d expect from a show conceived around a conference table, then executed by two network TV veterans with a budget befitting their track record but no personal connection to the premise. Carell stars as General Mark Naird, a proud Air Force lifer whose fourth star comes with the unenviable assignment to grow the President’s pet project Space Force into something more than a punchline. Thankfully, the closest the series gets to showing or even naming Trump are frequent references to “POTUS.” And POTUS demands boobs—er, boots—on the moon, STAT.

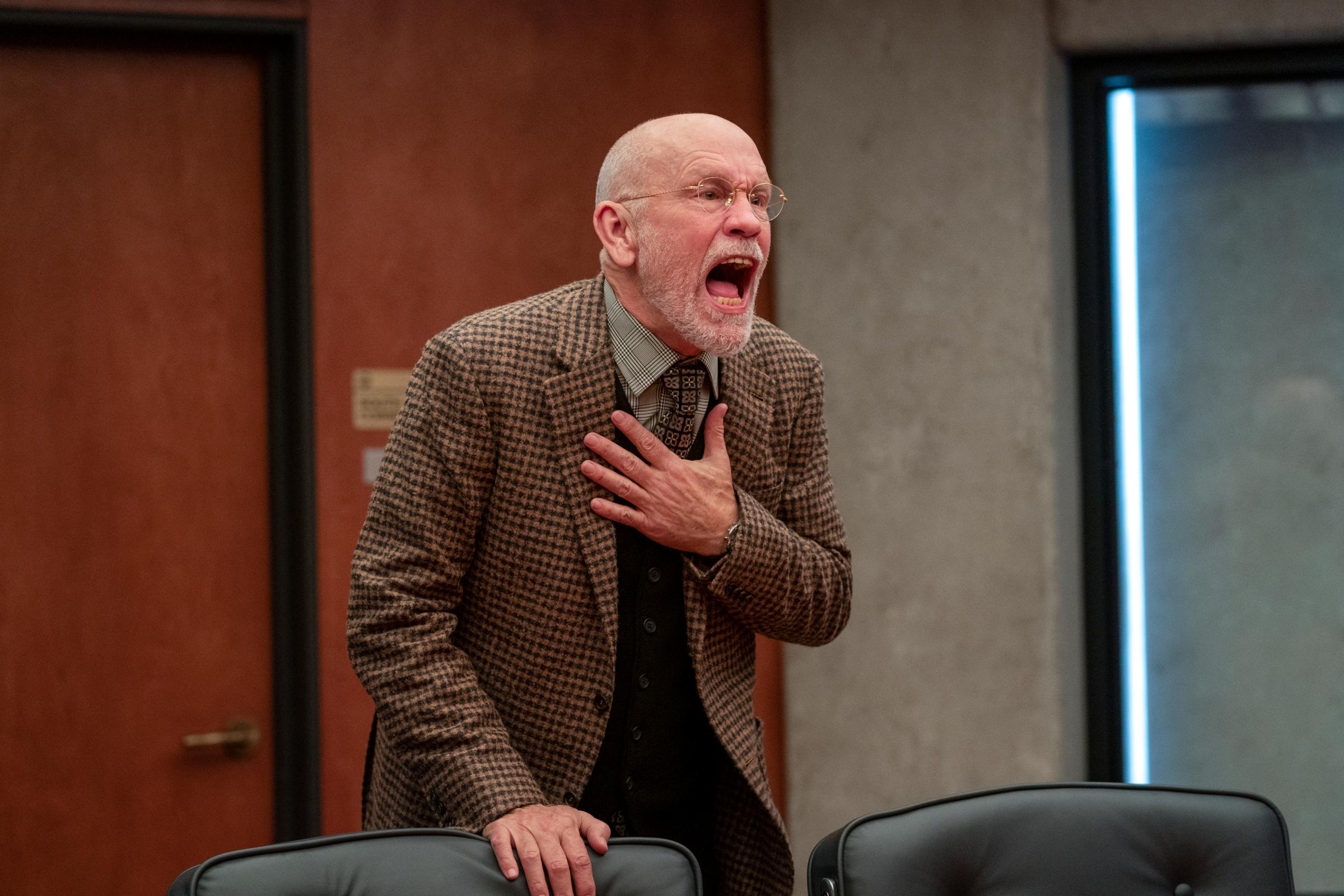

A prototypical Carell character, Naird is abrasive on the outside—in this case, he’s a stiff, impatient, xenophobic, anti-intellectual company man who speaks in an exaggerated gravelly growl—but kind within. By day, his default response to any obstacle is to bomb it; by night, he helps his sullen teenage daughter Erin (Diana Silvers) with her homework. But the show’s core is his relationship with Space Force’s lead scientist Dr. Adrian Mallory—a tweedy, perpetually exasperated John Malkovich type wisely underplayed by the real John Malkovich. The militarization of space makes Mallory apoplectic, but the buddy-comedy vibes are strong in this workplace sitcom, so he’s also inexplicably loyal to Naird. The real villain is the arrogant, competitive bully Naird left behind at the Air Force, Kick Grabaston (Noah Emmerich).

The production values are a giant leap ahead of Carell and Daniels’ last project. Instead of the purposely nondescript Dunder Mifflin cube farm, there’s a big, Brutalist Space Force campus, complete with mission control, labs, private offices and outdoor exercise space, plus scenes set everywhere from a congressional hearing to a simulated lunar colony. Yet characters spend a disproportionate amount of time interacting with or simply staring at an enormous screen in the control room. It all feels as different from The Office (and other workplace comedies of eras past) as the pioneering single-camera Office did from the multicam sitcoms that preceded it.

The supersize cast is another flex—one that backfires. Comedy greats are relegated to disappointingly small roles: Lisa Kudrow (who plays Naird’s wife), Jane Lynch (an imposing Joint Chief) and Fred Willard as Naird’s fragile father, in what must have been one of his final roles, only get a few scenes apiece. Others are misused. Jimmy O. Yang, who was hilarious as Silicon Valley’s vengeful Jian-Yang, plays it straight as Mallory’s deputy. It’s nice to see Daniels reunited with Ben Schwartz, who never failed to send me into hysterics as Parks and Recreation’s unctuous Jean-Ralphio—but Space Force saddles him with the same stale millennial-social-media-slash-publicity-guru character that has been obligatory on shows like this for more than a decade. Less recognizable actors like Tawny Newsome (Sherman’s Showcase, Brockmire), who plays an ambitious young pilot made to fly Naird around like an air chauffeur, don’t get enough time in the spotlight to shine. And that’s only about half the cast; there are so many characters, it takes more than half the season to get to know anyone besides Naird and Mallory.

Space Force has its moments, to be sure. In the premiere, our hero makes a show of pushing a giant launch button… and then we see it’s not plugged into anything. Cut to Mallory discreetly hitting the actual launch button. There’s a decent running gag in the fact that, just as the Air Force has airmen, soldiers are called “spacemen.” But, as with the other Daniels series that premiered in May, Amazon afterlife comedy Upload, even the highlights feel like holdovers from an earlier era of network sitcoms. Both shows make use—often to their detriment—of the larger budgets and longer runtimes streaming services allow without adapting to the medium’s constraints. Storytelling that’s less serialized than episodic is possible on streaming, yet the overarching plot of Space Force’s first season is so minimal and its episode formats so similar—they could all have titles along the lines of, “Naird and Mallory Play War Games,” “Naird and Mallory Hunt for a Spy in Their Midst,” etc.—that things can get repetitive when you watch more than one at a time.

Maybe the problem isn’t just the medium. Maybe Peak TV has changed popular tastes since the heyday of The Office and Parks and Rec, to the extent that a creator whose specialty is sitcoms in which relatively small casts of well-written characters wring humor out of everyday workplace scenarios might be forced into developing higher-concept material. Maybe the years when it was possible to make crowd-pleasing apolitical comedy about American politics are over. Or maybe Space Force was just never a viable idea outside the boardroom. Whatever the reason, Daniels and Carell might turn out to have made another hit, but they haven’t made another classic.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com