Through policies and power, leaders from New Zealand, France, India, China and the U.S. influenced the world more than any others in 2019. Here’s why these six were so important this year.

Xi Jinping, President of China

On Oct. 1, a parade of tanks, troops and nuclear missiles rolled through Beijing to mark 70 years since the founding of the People’s Republic. Standing before the Forbidden City, abode of emperors, China’s Xi Jinping vowed, “No force can stop the Chinese people and the Chinese nation forging ahead.”

Quite a few have tried this year. Nearly 2 million took to the streets to demand democratic reform in semiautonomous Hong Kong, where anti-Beijing candidates won a landslide in district elections. The trade war with the U.S. squeezed China’s growth to a three-decade low. The detention of over a million Muslims in the province of Xinjiang prompted condemnation by the U.N.

None have dented Xi’s resolve. Through propaganda and censorship, the Communist Party he leads has helped Xi turn external pressure into internal strength. His “China Dream” of returning his nation to “center stage” is battered but undiminished.

Still, there’s no denying that the tenor of China’s foreign relations changed in 2019. This was the year Xi went from strongman to bogeyman. In March, the E.U. branded China a “systemic rival.” In July, FBI Director Christopher Wray called the threat to society posed by China “diverse and wide and vexing.” Washington has demonized Chinese telecom firm Huawei and passed legislation in support of Hong Kong’s protesters. A bill still under consideration would sanction Chinese officials for “barbaric” human-rights abuses in Xinjiang, where 1 million Muslims have been detained.

And yet, Muslim leaders from Pakistan’s Imran Khan to Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman court Chinese investment. In November, Xi sipped wine with French President Emmanuel Macron in Shanghai before signing $15 billion worth of bilateral deals. And Taylor Swift opened Alibaba’s extravaganza for Singles Day, where $38 billion was spent.

The missiles and tanks were real enough. But Xi’s power, and fate, remains with what stands behind him: the capitalist might of communist China. —Charlie Campbell

Donald Trump, President of the United States

In his third year as President, Donald J. Trump physically walked into North Korea. He declared a national emergency for the U.S. border with Mexico. He recognized the disputed Golan Heights as a sovereign part of Israel. For any previous residents of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, one of these developments—unprecedented and historic—might have defined their presidency. For the 45th, they amounted to bullet points.

As America’s least orthodox Chief Executive rounds the corner into an election year, he is polishing his list of achievements. Trump has used the power of his office to roll back regulations, drive through a corporate tax cut and boost military spending. He takes credit for supercharging an economy that’s driven unemployment to record lows. He has also continued an uncharacteristically disciplined effort to reshape America’s federal courts, using Republican control of the Senate to appoint conservative judges who will define the laws of the land for a generation.

And yet the Trump presidency may well pivot on his forays into a world that typically interests him the way a shop window does—in passing and for his reflection in it. The year began, after all, in suspense over special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russia’s actions to help Trump’s 2016 campaign. The dense final report was, in its detail, damning: Mueller presented at least 10 times the President may have attempted to obstruct the probe, a criminal offense. But Trump claimed “complete exoneration” on the marquee allegation, that he had sought assistance from a foreign power on his effort to win election. And then, the day after Mueller testified on Capitol Hill, Trump telephoned the leader of another foreign country, Ukraine, and sought assistance on his effort to win re-election by investigating Democratic rival Joe Biden and his son. Thus did the year draw to a close with the U.S. House of Representatives preparing articles of impeachment that, even if voted down in the Senate, will define Trump in history. The question is: Will that matter in the realms the incumbent values most? There is still no person whom taxi drivers, news anchors, hairstylists, foreign leaders and voters talk about more. And for Trump, that may be enough. —Brian Bennett

Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives

The temperature in Washington changed on Jan. 3 when Nancy Pelosi picked up the gavel and became Speaker of the House for a second time. President Donald Trump has yet to recover.

For two years, Trump had benefited from a subservient Republican Congress. Pelosi quickly made clear that divided government would be a different story. Taking the reins in the midst of the longest government shutdown in history, she refused to cave to Trump’s demand for a border wall, waiting him out—and canceling the State of the Union address—until he surrendered. Over the ensuing months, she served as the unorthodox President’s foil, using her mastery of the powers of the Legislative Branch to hold Trump in check.

For much of the year, Pelosi battled the left nearly as much as the right, frustrating progressive activists and far-left members by steering her party toward the center. Even as she’s overseen an unprecedented slate of investigations into the Executive Branch, she’s tried to find ways to work with Trump where possible. At the White House’s request, Pelosi passed a $4.6 billion border bill with funding for the immigration detention centers the left considers concentration camps, and later negotiated a two-year budget agreement that increases military funding. She’s kept trying to make deals with Trump on prescription-drug pricing and infrastructure, even as the President has repeatedly walked away from the table. Of the more than 300 bills the House has passed that sit on the Senate’s doorstep, more than 275 are bipartisan.

On Dec. 10, Pelosi announced the House’s articles of impeachment of Trump. An hour later, she unveiled an agreement on the President’s plan to update the North American Free Trade Agreement. The split screen epitomized her yearlong high-wire act. Pelosi resisted Democrats’ calls for impeachment until the Ukraine scandal forced her hand. As the year ends, the results-oriented leader finds herself in just the situation she’d tried to avoid: a partisan impeachment of a President unlikely to be chastened by it. The founders’ vision for checks and balances has forced her into a historic confrontation, with unforeseeable consequences. “If we had not done this,” she tells TIME, “just think of how low our democracy would have sunk.” —Molly Ball

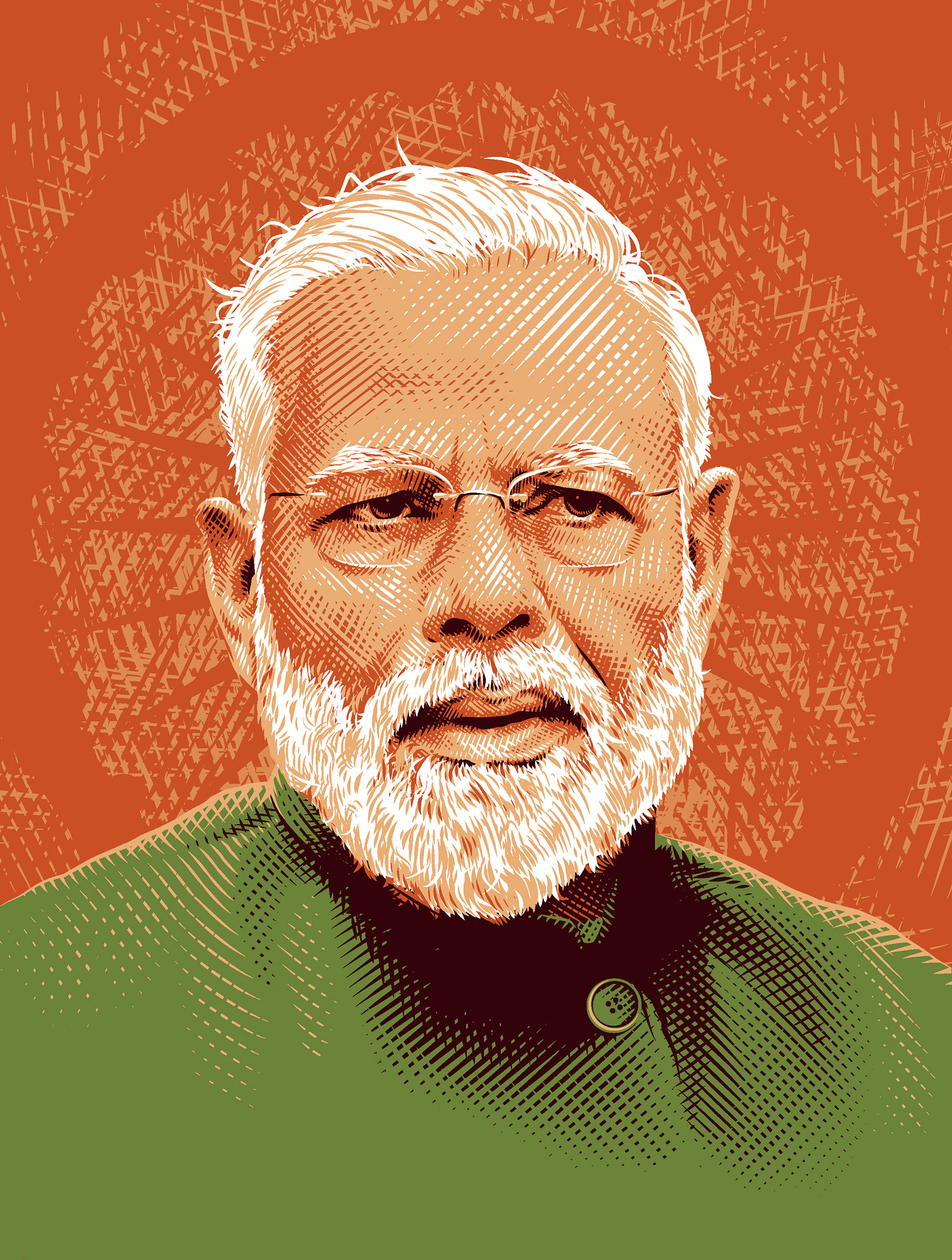

Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India

For decades after the British departed the Indian subcontinent, its history was one of painful cleavings. The 1947 Partition is a bland label for a division that produced two countries, 15 million refugees and at least a million deaths. When Pakistan, founded as a Muslim homeland opposite a secular India, itself split in two, the war that created Bangladesh in 1971 undid the assumption that a common faith alone could bind a nation. But in 2019, Narendra Modi began his second term in office having revived the premise in India.

In May, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won a months-long election in a landslide that established Modi as the most powerful Prime Minister in more than a generation. But as Modi has consolidated power, India’s Muslims—who make up 14% of the country’s population—are questioning whether they count as Indian anymore. The BJP exalts Hindu nationalism, the identity politics of a religious majority that has been emergent for decades but for which Modi’s unprecedented majority marks a historical high watermark.

When the Dalai Lama spoke with TIME in the Himalayan foothills where he lives in exile from Tibet, he repeatedly praised India’s tradition of multifaith harmony. The country’s 1.3 billion people include not only Hindus and Muslims, but also Christians, Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists. But Modi has abandoned that tradition, becoming instead a hero to Hindu extremists. In August, the Prime Minister revoked the constitutional autonomy of Kashmir, India’s only Muslim-majority state, imposing a curfew and imprisoning political leaders. His government is pushing through new measures that could make it easier to imprison and deport Muslims who cannot prove their Indian citizenship, even if they have lived in the country for generations.

Abroad, however, Modi retains the image etched early in his first term, of a populist economic reformer toting a yoga mat. In September a crowd of some 50,000 attended a “Howdy Modi” rally in Houston, with President Trump in the front row. But India’s renown as the world’s largest, most vibrant democracy is being tested by Modi’s divisive politics. Now, with an enormous mandate, he can govern almost as he pleases. —Billy Perrigo

Jacinda Ardern, Prime Minister of New Zealand

The gesture was simple, but the effect was profound. Less than 24 hours after a far-right extremist massacred 50 worshippers in two Christchurch mosques in March, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern put on a black hijab to meet members of the Muslim community, hear their fears and share in their grief. In one photograph of the encounter, the young leader’s brow is lightly creased and her mouth turned down, an uncanny expression of empathy mixed with strength. The obscenity of the slaughters has been compounded by being livestreamed. But here was a still frame that, as it spread beyond the heartbroken island nation, would endure as an emblem of compassion, tolerance and resolve.

When Ardern took power in October 2017 at the age of 37, it was as the world’s youngest female leader. She advanced a range of progressive policies, with a particular focus on the environment. Under Ardern, New Zealand’s government banned single-use plastic bags, planted 140 million trees and passed a bill to set a net-zero target for CO emissions by 2050. She also extended paid parental leave and took six weeks off herself after giving birth while in office—a rare example of a head of state taking parental leave of any length.

Yet it was in her response to tragedy that Ardern emerged as an icon. The purpose of terrorism is to scare and divide. And so the Prime Minister reassured and united. She immediately made herself available to her fellow citizens, particularly those who felt most vulnerable. She kept attention focused on the affected by refusing to utter the killer’s name. And she channeled the grief and rage of her country into meaningful change, pushing through reforms of gun laws only days after the attack.

New Zealand votes again in 2020, and despite Ardern’s popularity her party is trailing in the polls. While she remains in power, she is intent on using it against the scourge of far-right extremism, urging fellow heads of state to join the Christchurch Call, a pledge to work together to stem terrorist content online. But whatever the election brings, the world has seen what leadership looks like. —Dan Stewart

Emmanuel Macron, President of France

When Emmanuel Macron was elected in May 2017, he strode into his victory celebration not to the sounds of “La Marseillaise” but to Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” the anthem of the European Union. Now, halfway through his five-year term, the French President has finally emerged as the de facto leader of the Continent.

With German Chancellor Angela Merkel drifting toward retirement, and Britain searching desperately for Brexit, the French leader has seized on seemingly every simmering transnational issue as though he were an indispensable part of its solution: climate, global trade, Iran sanctions, Russian aggression and China’s superpower rivalry.

A theater actor in his high school days, this year Macron has cast himself as a global decision-maker. In November, he bluntly pronounced NATO dysfunctionally “brain dead,” again suggesting that the E.U. needs its own military alliance. In Beijing that same month, he reviewed Chinese troops with President Xi Jinping and sealed trade and climate deals, rendering the E.U.’s new trade commissioner a bit player.

Feeling empowered in Europe, Macron also seems to be done with courting President Donald Trump. During a joint press appearance in London on Dec. 2, Macron turned the tables on his U.S. counterpart, cutting short an offhand comment about ISIS fighters. “Let’s be serious,” Macron snapped, with a hint of exasperation that left Trump uncharacteristically flustered.

At home, however, Macron faces enduring fury. Having struggled through the violent protests of the Yellow Vest revolt of 2018, he is back to his reform agenda, vowing to end sweetheart pension deals that France can no longer afford. He was rewarded with the biggest national strikes in many years in December, and a full-blown resurgence of the Yellow Vests may be on the horizon. Among the hundreds of thousands of strikers who poured into the streets, some of them chanted “Macron dégage!” or “Macron out!”

Voters will get their chance to make that a reality in 2022. Until then, France’s President will be busy cementing the role he always saw for himself—at the helm of Europe. —Vivienne Walt

This article is part of TIME’s 2019 Person of the Year package. Read more from the issue and sign up for the Inside TIME newsletter to be the first to see our cover every week.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com, Molly Ball at molly.ball@time.com and Billy Perrigo at billy.perrigo@time.com