As Pete Buttigieg addressed supporters off a back porch in Marshalltown, Iowa, the Devil was whispering his name. “Pete,” the Devil hissed into a microphone. “You’re sooo smart, Pete.”

Buttigieg ignored the heckler, plowing forward with his stump speech about American decency as his husband Chasten looked on. “Pete,” the Devil whispered. “I want the heartland, Pete.”

The man in the devil costume was Randall Terry, an antiabortion activist. He had traveled to Iowa to torment the 37-year-old mayor of South Bend, Ind., the early breakout star of the 2020 Democratic presidential primary. “There’s never been a poster boy for homosexuals” before, Terry says. “There’s never been a homosexual that you’d go, ‘Wow, I’d be proud of him.’ He’s the guy. That’s why he’s such a threat.”

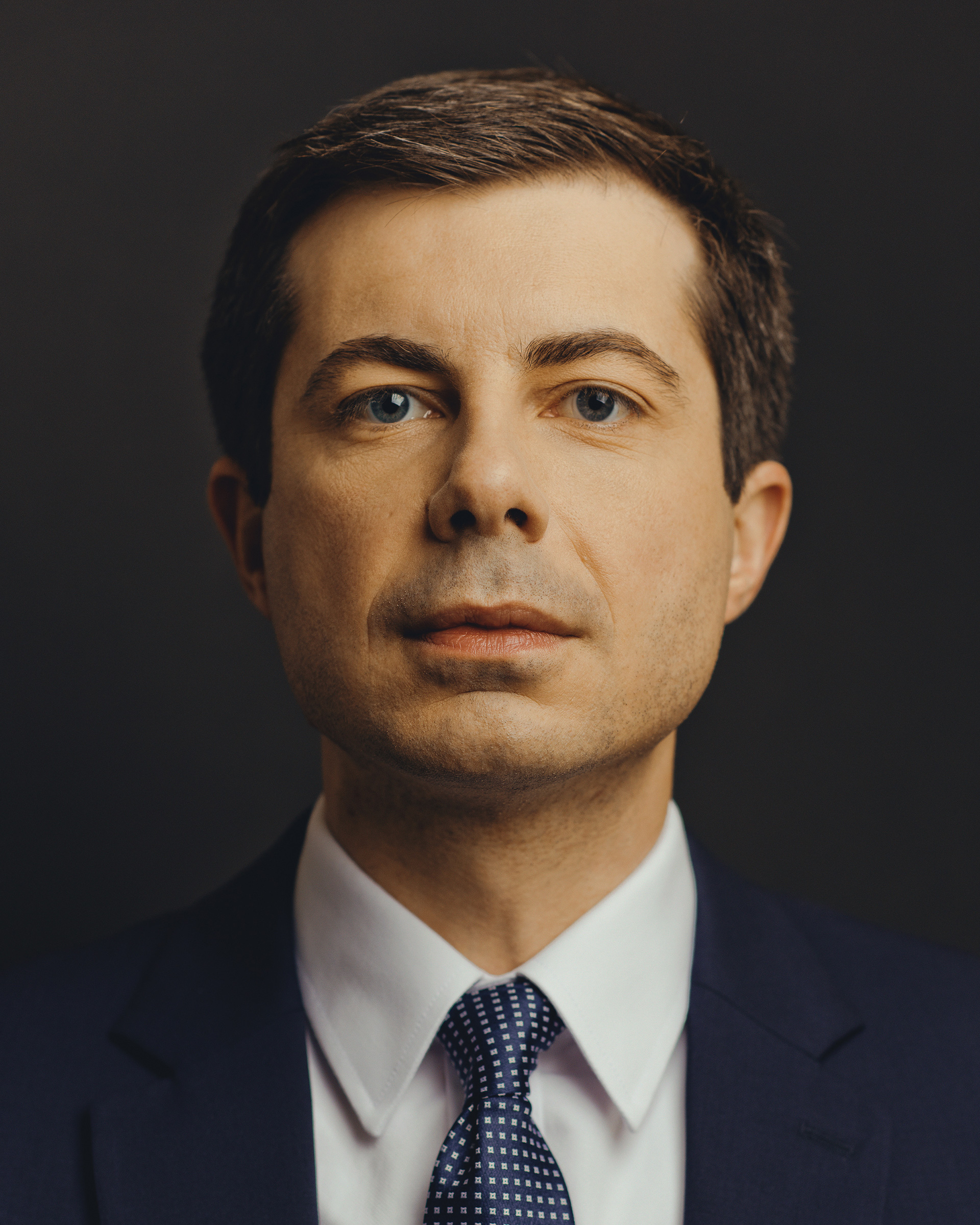

Four years after the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed his right to marry, Buttigieg has become the first openly gay person to make a serious bid for the presidency. And Terry is hardly the only right-winger worried about the rise of “Mayor Pete.” Buttigieg’s saying that “God doesn’t have a political party” prompted evangelical leader Franklin Graham to tweet that being gay is “something to be repentant of, not something to be flaunted, praised or politicized.” Concerned by the campaign’s rise, right-wing provocateur Jacob Wohl was recently caught trying to fabricate sexual-assault allegations against Buttigieg to slow him down.

But to some Americans, Buttigieg may just be the man to vanquish America’s demons. In a field of more than 20 candidates—including six Senators, four Congressmen, two governors and a former Vice President—Buttigieg (pronounced Boot-edge-edge) has vaulted from near total obscurity toward the front of the Democratic pack, running ahead of or even with more established candidates and behind only Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders.

Buttigieg is a gay Episcopalian veteran in a party torn between identity politics and heartland appeals. He’s also a fresh face in a year when millennials are poised to become the largest eligible voting bloc. Many Democrats are hungry for generational change, and the two front runners are more than twice his age.

Watch: How Mayor Pete Buttigieg became a surprise contender in the 2020 Democratic primary

But Buttigieg’s greatest political asset may be his ear for languages. He speaks eight, including Norwegian and Arabic, but he’s particularly fluent in the dialect of the neglected industrial Midwest. Buttigieg is a master of redefinition, a translator for a party that has found it increasingly difficult to speak to the voters who elected President Donald Trump. The son of an English professor and a scholar of linguistics, he roots his campaign in an effort to reframe progressive ideas in conservative language. “If the substance of your ideas is progressive but there’s mistrust about them among conservatives, you have three choices,” Buttigieg tells TIME, sitting on his living-room couch in South Bend. “One is to just change your ideas and make them more conservative. The second is to sort of be sneaky and try to make it seem like your ideas are more conservative than they are. And the third, the approach that I favor, is to stick to your ideas, but explain why conservatives shouldn’t be afraid of them.”

His platform is “Freedom, Security and Democracy,” which wouldn’t sound out of place coming from a Bush-era Republican yet actually harks back to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. But in order to maintain his momentum, Buttigieg will have to do more to flesh out those ideas. Unlike many of his opponents, he hasn’t posted any detailed policy proposals on his website. He’ll also have to convince Democratic voters that his experience running South Bend (pop. 102,245) is adequate preparation for running the world’s most powerful country. And he’ll have to make inroads with black and Hispanic voters who have so far appeared unimpressed with his campaign.

Buttigieg likes to say he has more government experience than Trump, and more military experience than any President in 25 years. And Trump’s victory in 2016 proved that many Americans were willing to elect a President without a traditional Washington résumé. But some voters long for stability after three years of chaos, and it’s not clear whether the Trump presidency has made it easier or harder for outsiders.

The same assets that have propelled Buttigieg so far could ultimately thwart his rise. His youth is appealing to many voters, but it also means he’s green. The idea of electing the first gay President thrills liberals, but it also rallies opponents. As a white man, Buttigieg may appeal to more traditional voters, yet women and voters of color are the heart of the Democratic coalition. He’s running as a healer, not a fighter, at a moment when the party seems to be in a fighting mood. “As a woman of color, it’s very difficult for me to hear ‘We can unite across our differences,’” says Democratic operative Jess Morales Rocketto. “On one side you have people who want to live in a white-supremacist country, and on the other side you have people dying at the hands of white supremacists.”

In many ways, Buttigieg is Trump’s polar opposite: younger, dorkier, shorter, calmer and married to a man. His success may depend on whether Democrats want a fighter to match Trump, or whether Americans want to “change the channel,” as Buttigieg puts it. “People already have a leader who screams and yells,” he says. “How do you think that’s working out for us?”

On a Sunny Monday morning, Buttigieg is musing about redeeming American credibility abroad, sipping from his coffee mug emblazoned with JFK’s face, when his husband plops onto the living-room couch, picks up the blanket next to him and throws it on the floor in mock disgust. “Do we have to have this hideous blanket?” he said. The blanket is full of dog hair. “Can we put our nice blanket there?”

The hair comes from Truman, their hound mix, and Buddy, their tubby rescue puppy. When I first met Buttigieg in 2017, he told me he named Truman after a famous saying often attributed to the 33rd President: “If you want a friend in Washington, get a dog.”

But you live in South Bend, I said. When are you planning on moving to Washington? He didn’t reply.

The house looks like it’s occupied by moderately tidy people who travel a lot. Coats are piled on the bannister, and old sneakers and a pair of Crocs are lined up next to the kitchen door. A tiny photo of Pete and Chasten with Cher peeks out from behind wedding save-the-dates posted on the fridge. The kitchen walls are a too-bright yellow. The mayor painted them himself, which he says was a mistake.

Buttigieg met Chasten Glezman, then a Chicago grad student, on the dating app Hinge in 2015. They talked over FaceTime for a few weeks before Chasten drove to South Bend for their first real date, at an Irish bar famous for its Scotch eggs. Less than three years later, Pete proposed in gate B5 of Chicago’s O’Hare airport, the exact spot where Chasten had first noticed his dating profile.

Their marriage is at once banal and extraordinary, infused with the exuberant contentment of two people who once thought they would always be alone. Chasten handles the dogs, the shopping, the cooking. Pete does the dishes, laundry and garbage. Chasten hates taking the bin out to the curb. Pete hates the way Chasten folds T-shirts. Chasten gets grumpy when they go too long without food, and Pete doesn’t get it. “You’re like, ‘Oh, here, I packed a bag of almonds and a thing of beef jerky,’” Chasten says. “I hate nuts, and he eats nuts all the time.”

“High in protein, good for you,” Pete counters.

“See!” Chasten says. “I want a meal, and he’s like, ‘We’ll just have a handful of nuts.’” Also, he tells his husband, “You do chew really loudly.”

Both men grew up closeted in conservative Midwestern communities. “Being gay was not culturally acceptable where I grew up, mostly for a lack of understanding,” Chasten says. “And so my family and I were just at a crossroads, and we didn’t really know how to talk to one another.” When he came out after his senior year of high school, tensions at home forced him to spend months crashing on friends’ couches and sleeping in his car. His parents ultimately changed their minds, welcomed him back home and now fully support their son and his marriage.

Pete took a lot longer to come to terms with himself. As a child, “he was an observer,” recalls his mother Anne Montgomery. “Each time he went to a new school, he’d sit there and watch who was doing what and why.” In high school, he was elected senior class president and played Theseus in a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the voice of sanity and order in a world gone mad. He won the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library’s Profiles in Courage contest for an admiring essay about Bernie Sanders—20 years before challenging the Vermont Senator for the Democratic nomination.

Alone with the knowledge that he was, as he put it, “really strongly attracted to other young men,” he threw himself into his studies, teaching himself languages and musical instruments and reading James Joyce. One Harvard roommate recalled he had learned circular breathing in order to hold a note on the didgeridoo. He lived with a handful of guys in a suite nicknamed the Château because of its fancy moldings and exposed brick walls. He was the roommate who would sip whiskey instead of chugging beer, and insist on a real Christmas tree in the dorm room. He dated women occasionally but never joined his roommates’ discussions of their sex lives.

After graduation, Buttigieg went to Oxford on a Rhodes scholarship, then did a brief stint at the consulting firm McKinsey, analyzing grocery-store pricing. He moved back to Indiana and joined the U.S. Navy Reserve in 2009, before the repeal of “Don’t ask, don’t tell.” He remembers his fellow officers tossing the word gay around as an insult, the way middle schoolers once did.

In 2010, at the age of 28, he ran his first political campaign, for Indiana state treasurer, and got crushed, losing by 27 points. But the following year, Buttigieg ran for mayor of South Bend and won. He was professionally ascendant but personally adrift: friends were starting to meet serious girlfriends, get married, have kids, and Pete’s personal life amounted to watching The Simpsons alone with a beer after work. He was deployed to Afghanistan in 2014, halfway through his first term as mayor. When he came back six months later, he says, he realized that if he had died overseas, he would have never known what it was like to be in love.

In 2015, just as Buttigieg was beginning to come out privately to friends and family members, Indiana’s then Governor Mike Pence signed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which allowed local businesses to discriminate against LGBTQ people. Later that year, at the height of his re-election campaign, Buttigieg wrote an op-ed in the South Bend Tribune to announce he was gay. It was more of a personal calculation than a political one, he says: given his job, he couldn’t openly date until his constituents knew the truth. He feared it would cost him re-election, but he won with 80% of the vote.

It was a sign of how rapidly public opinion on LGBTQ issues has changed. In 1996, only 27% of Americans supported same-sex marriage; today 67% do, including 44% of Republicans. Some of Buttigieg’s fellow officers who had used gay as an epithet in his presence reached out to express their support. “I bet some of them still go back and tell gay jokes because that’s their habit, you know?” he says. “Bad habits and bad instincts is not the same as people being bad people.”

All this informs his belief that it’s still possible to reach across America’s political divide. “We’ve got to get away from this kill-switch mentality that we see on Twitter,” he says. He has seen once disapproving parents dance at their gay son’s wedding and homophobic military officers take back their words, and so he believes in the power of redemption and forgiveness. “This idea that we just sort people into baskets of good and evil ignores the central fact of human existence, which is that each of us is a basket of good and evil,” he says. “The job of politics is to summon the good and beat back the evil.”

For the mayor of a place like South Bend, politics gets a little more complicated. When Buttigieg was elected in 2011, his mandate was to turn around a dying city. South Bend had been in decline since 1963, when the Studebaker auto company left, taking thousands of jobs with it. Buttigieg got to work. He made downtown more walkable, improved infrastructure for filling potholes and plowing snow, and brought new companies to South Bend through partnerships with Notre Dame. “Mayors in the past had kind of a can’t-do attitude,” says veteran South Bend Tribune columnist Jack Colwell. “When people came to talk to Pete, he’d say, ‘How can we help you get this done?’”

In interviews with local residents, nearly all said Buttigieg had done a generally good job as mayor, though some said he had blind spots on issues affecting black and Hispanic residents. Early in his tenure, Buttigieg fired a popular black police chief who was under FBI investigation for wiretapping white officers who had been suspected of using racist language. And while most residents say the city improved under his leadership, the gains have not been evenly distributed. South Bend still has a persistent racial wealth gap: black households earn roughly half of what white households make, and the black poverty rate is almost twice the national average, according to a 2017 Prosperity Now report commissioned by Buttigieg’s office. Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, the researcher who compiled the report, said Buttigieg was the first mayor of any city to ask him to do this. “He didn’t solve racial economic inequality,” says Asante-Muhammad, “but what city has?”

One of Buttigieg’s main goals was to improve the city’s housing stock. South Bend had a glut of abandoned homes left over from the Studebaker heyday, and Buttigieg announced a plan to either tear down or fix up 1,000 in 1,000 days. Almost immediately, black residents expressed concern. Most of the vacant homes were in black and Hispanic neighborhoods on the town’s West Side. While no families reported being evicted because of the policy, some locals had bought or inherited vacant homes intending to fix them up, then faced heavy code-enforcement fines or even lost the properties they had purchased. Regina Williams-Preston, a teacher whose family has lived on South Bend’s West Side for years, had purchased several abandoned homes in order to renovate them later, but says she lost them to Buttigieg’s policy after her husband got sick and they couldn’t make the repairs.

In the wake of Buttigieg’s campaign boom, Williams-Preston has been escorting national reporters around South Bend, pointing out the areas where his housing policy failed. “He was young and bright and had a lot of really good ideas,” she says, driving through neighborhoods with rundown houses next to overgrown lots. “But he didn’t have the lived experience, the ability to really connect with real people who have real issues and real problems that life hasn’t dealt the best hand.”

Other black leaders in South Bend say Buttigieg listened to the concerns of the community and adjusted when he was wrong. “I trust him,” says Stacey Odom, founder of a local organization that helps families on the West Side repair their homes. “I asked him for five different things, and he gave them all to me.” Buttigieg created an office of Engagement and Economic Empowerment to help address the wealth gap, and issued an executive order on diversity and inclusion in response to local demands, Williams-Preston said. When local leaders asked for $3.5 million to renovate the Charles Black community center, Buttigieg came up with $4.5 million, according to Cynthia Taylor, the center’s director. “You’re gonna have to invite him in, you’re gonna have to sit him down, you’re gonna have to show him the issue,” she says. “Because he definitely will listen.”

Williams-Preston, who’s now running to replace Buttigieg as mayor, says he sometimes seemed insufficiently angry about the inequities in South Bend. She’s looking for a President who has “a deep passion for justice, a deep drive for equality.” She voted for Sanders in 2016 and describes herself as a “Berniecrat.” But as she drives her minivan around the West Side, pointing out grassy areas where vacant houses once stood, she’s wearing a Pete button on her jacket.

Buttigieg may be a loyal son of South Bend, but he keeps angling for a job transfer out of town. In 2017 he ran for chair of the Democratic National Committee. After he lost, he asked his old friend Mike Schmuhl to move back to South Bend to help him run his political-action committee. He never actually told him he was planning to run for President. “It was unspoken,” Schmuhl says.

There are two main types of presidential candidates: those who run on policy and those who run on personality. Buttigieg says he’s a “policy guy,” but he’s definitely a personality guy. His campaign is more about who he is (young, gay, Midwestern, technocratic) and what he represents (social progress, generational change, an olive branch to “flyover country”) than what he’ll do if he’s President.

So far Buttigieg has embraced a few big ideas, such as abolishing the Electoral College and expanding the Supreme Court. (Both would require an improbable constitutional amendment.) But when it comes to the policy issues dominating the primary so far, he has staked out only general positions. On health care, he favors “Medicare for all who want it.” He supports an “intergenerational alliance” to fight climate change and calls the Green New Deal “the right beginning.” He said he wants to “do some math” around Senator Elizabeth Warren’s plan to make college free and forgive student debt. Warren, for her part, has 11 policy proposals on her website. Buttigieg has zero.

“Every good policy that I’ve developed in my administration happened not because I cooked it up on the campaign, kept the promise intact and then delivered it,” he says, “but because I stated a priority in one of my campaigns, interacted with my legislative body and my community, and developed something that really served people well.”

Does this mean that he thinks policy is less important than narrative? “Maybe I’m saying the narrative is policy,” he responds, in a typical attempt at reframing. “Narrative is how you get people to embrace the policies you’re putting forward.” His campaign plans to release more detailed policies this week.

“Running a campaign based on narrative has long been a privilege reserved for men. And Buttigieg’s maleness and whiteness has undoubtedly benefited him, even as women and people of color become increasingly central to the Democrats’ 2020 coalition. He knows this and acknowledges that “it’s hard for me to even be able to see some of the ways in which whiteness or maleness may have made my life go differently,” adding that it has likely affected the way he’s been covered by the national media.

At the same time, Buttigieg’s sexuality has imbued his campaign with a sense of historical promise. After the valedictorian at Brigham Young University, a conservative Mormon school, came out as gay in his commencement speech in April, he cited Buttigieg as his inspiration. (“I know that kid is going to make it easier for somebody else,” Buttigieg told BuzzFeed News.) Buttigieg’s campaign has also gotten a boost from a network of wealthy LGBT donors.

The millennial mayor’s call for generational change could also prove to be a powerful one. Even as young voters stay enamored with Sanders, older voters seem attracted to Buttigieg’s youth: according to an April 29 Morning Consult survey, his highest polling numbers come from baby boomers. “I like the idea of a millennial,” says Alice Mayer, 62, who voted for Sanders in 2016, as she waited for Buttigieg’s speech in South Bend. “He’s looking at the future, while Bernie’s been there, done that.”

Buttigieg has spent years thinking about how Democrats can reclaim the language of patriotism from Republicans. “The real challenge for the Democratic Party, and its presidential candidates in particular,” he wrote in a 2003 column in the Harvard Crimson, “is to figure out how to reverse the Right’s stranglehold on our political vocabulary.” Soon after, he wrote another column urging Democrats to reclaim words like compassion, strength and morality, arguing that “establishing a new vocabulary is not the point; we need to take the old vocabulary and make it make sense again.” More than any health care plan or climate-change policy, Buttigieg wants to change how Democrats talk. “The landscape can be moved,” he says. “But to move it, I don’t think you just run in and beat people over the head with your way of talking about your ideas the way you always have.”

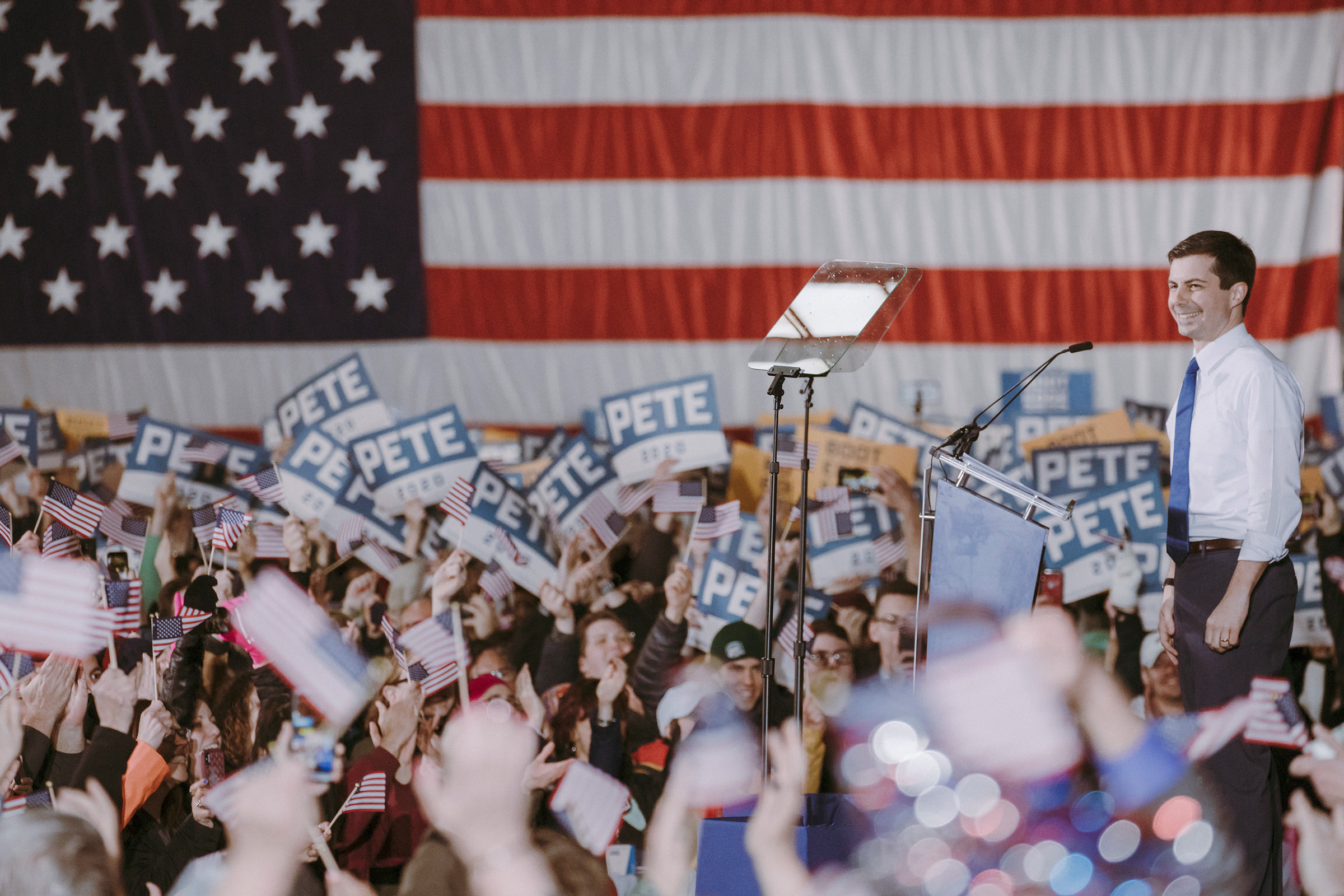

When Buttigieg announced his exploratory committee in January, in a drab conference room at a Washington Hyatt, his staff was mostly just Schmuhl, his high school buddy turned campaign manager, and Lis Smith, a New York operative who helped Buttigieg run his long-shot campaign for DNC chair. Three months later, the staff has swelled to nearly 50 as Buttigieg bounces between rallies in Iowa and New Hampshire, fundraisers with bundlers and TV appearances everywhere.

Buttigieg has been ubiquitous by design. The campaign’s goal is to “break down the wall that exists between presidential candidates and the media, and therefore the public,” Smith says. The Buttigieg campaign has no digital department, according to Schmuhl, because it weaves digital media into everything it does. Instead, the campaign has an “experience team,” which focuses on everything from events to content. The campaign shared its logos and designs in catchy Instagrammable images, complete with a color palette so that fans can spread the Buttigieg brand on social media. It’s also rethinking the value of paid television advertisements, reasoning that most millennials watch TV through streaming services on their computers and phones.

Despite these new strategies, some of the old truths still hold. It remains almost impossible to win the Democratic nomination without significant support from black voters, and the Morning Consult poll found negligible black support for Buttigieg. The mayor is working on his outreach, eating lunch with the Rev. Al Sharpton at the famous Harlem soul-food joint Sylvia’s and scheduling a swing through South Carolina for early May. But winning voters of color may be difficult for a white guy running against two black Senators, Kamala Harris and Cory Booker, as well as Joe Biden, who served as Barack Obama’s running mate and has long-standing relationships in black communities.

In a primary divided between candidates who want to fight Trump and candidates who talk about uniting the country, Buttigieg is in the latter camp. That puts him out of step with the party’s activist base, who clearly want a fighter. Warren, for example, used the word fight 25 times in her announcement speech; Buttigieg didn’t mention it once. His husband says he’s never heard him raise his voice in anger. “We’ve almost fetishized fighting,” Buttigieg explains, sitting in his living room between an antique British musket and an old Soviet spying device, both relics of old and painful wars. “There is a point where you become so absorbed in fighting that you begin to lose track of winning.”

In the end, Buttigieg’s biggest gamble is his bet that voters are sick of a divided America and hungry for reconciliation. He believes independents and moderate conservatives could get behind a happily married Christian veteran. And he may be right. “Pete has a way of rallying people and getting them to come along with him,” says Jake Teshka, former executive director of the St. Joseph County GOP and the only Republican on the South Bend city council. “That’s what makes him dangerous as a candidate for the rest of the Democratic field. I can’t sit here and tell you that if he makes it through and he’s on the ballot in 2020 that I would vote for Pete. But I also can’t tell you that I won’t.”

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity