Lori Alhadeff is haunted by the fact that she did not send her 14-year-old daughter to school with a bulletproof backpack. The mother of three had wanted to buy one but never got around to it. By Feb. 14, 2018, it was too late. Her first child, Alyssa, was fatally shot trying to hide under a classroom table at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla. “I wish to this day that I did give that protection to Alyssa. It could have saved her life,” Alhadeff says. “Obviously, I regret that.”

After the massacre, which killed 16 others, Alhadeff bought bulletproof backpacks for her two sons, who are now 14 and 12. “I have peace in my heart for my two boys, at least, that I’m doing everything in my power to protect them,” says Alhadeff, who won’t let her sons go to school without the backpacks.

With more than 69 people killed so far in mass shootings in the U.S. in 2019, thousands of Americans like Alhadeff are seeking security through an explosion of products marketed to those scared of being shot or of losing loved ones to gun violence. Backpacks that double as shields are sold by major department stores, including Home Depot and Bed, Bath & Beyond. There are bulletproof hoodies for children as young as 6; protective whiteboards and windows; armored doors and anchors designed to keep shooters out of classrooms; and smart cameras powered by artificial intelligence that alert authorities to threats. In Fruitport, Mich., officials are building a $48 million high school specially designed to deter active shooters, with curved walls to reduce a shooter’s line of sight, bulletproof windows and a special locking system.

In 2017, U.S. schools spent at least $2.7 billion on security systems, and that’s on top of the money spent by individuals on things like bulletproof backpacks, the IHS Markit consulting firm reported. Five years ago, in 2014, the figure was about $768 million, IHS said. But school shootings haven’t decreased in frequency, and critics of the growing industry in bullet-resistant items say the only beneficiaries of these so-called security measures are the people making money off of them.

“These companies are capitalizing on parents’ fears,” says Shannon Watts, a mother of five who founded the gun control advocacy group Moms Demand Action following the 2012 Sandy Hook massacre that killed 20 first-graders and six educators.

In September, as students were returning to school, Sandy Hook Promise, a gun violence prevention nonprofit led by family members of Sandy Hook victims, released a video that used biting satire to highlight the bulletproof industry and the country’s failure to prevent mass shootings. It shows cheerful children returning for classes and using their new clothes and back-to-school supplies to save themselves and others from a shooter. One boy shows off his new skateboard, then uses it to smash a window and escape; a girl demonstrates how her new socks can be used to tie a tourniquet; another uses her jacket to lock a set of double-doors. The message is clear: these shootings should be prevented before kids get to the point of using tube socks to save classmates from bleeding to death.

But with efforts at gun control legislation stalled as the Senate refuses to take up a House-passed bill that would require background checks for private gun sales, even critics of the booming security industry concede it’s unlikely to slow down. “There’s not a parent in the country who isn’t worried that their child will be the next victim of gun violence,” Watts says.

According to the Gun Violence Archive, there have been more than 330 mass shootings—in which at least four people other than the shooter were injured or killed—so far this year in the United States. This summer alone, 31 people were killed in back-to-back mass shootings in El Paso, Texas and Dayton, Ohio and another 10 died in attacks in Gilroy, Calif. and Odessa, Texas. In the aftermath of each tragedy, companies saw striking growth in profits. “It’s a business fueled by fear,” says Sean Burke, president of the School Safety Advocacy Council, which works with school districts and police departments.

TuffyPacks, an online retailer selling ballistic shields that are inserted into backpacks, reported up to a 500% increase in sales after the shootings in El Paso and Dayton in early August, which coincided with back-to-school shopping season. “Every time shootings occur, we see spikes in sales,” says TuffyPacks CEO Steve Naremore, 63, of Houston, Texas, who insists his company’s $129 inserts are no different from other safety equipment, like fire extinguishers and bicycle helmets. Guard Dog Security, a competing company that sells bulletproof backpacks that weigh up to 4.5 pounds and can cost up to $299, couldn’t keep up with the orders. “They were selling out faster than we could get it back in stock,” says Yasir Sheikh, its 34-year-old CEO. Sheikh—who like Naremore declined to disclose revenue figures—launched his company in 2009 but didn’t see a huge demand until Sandy Hook.

The demand that follows mass shootings prompted Vy Tran, 25, to quit her job and use $100,000 in savings and retirement funds to start selling homemade bulletproof hoodies. Her company, Wonder Hoodie, began as a side business, which she launched after her next-door neighbor, a mother of two, was shot dead in their Seattle neighborhood during an attempted robbery in 2016.

Panicked after the killing, Tran says she searched online for body armor to protect her mother and younger brother, but the products she found were either too expensive or too heavy. So Tran, a health and safety consultant, decided to make them herself, using Kevlar that she ordered online. Tran was making an average of one or two hoodies a week until 58 people were killed at a Las Vegas music festival on Oct. 1, 2017 in the worst mass shooting in modern history. Sales spiked, and there were suddenly 10 to 15 requests pouring in every day.

“I couldn’t keep up with the orders,” says Tran, who hired a team to help her. Wonder Hoodie has since fulfilled almost 1,000 orders for hoodies that cost up to $600 and weigh up to 9 pounds.

It’s not just young and new CEOs leaping into the growing field of gun safety products, and the merchandise isn’t all body armor. Chris Ciabarra and Lisa Falzone of Austin, Texas, launched Athena Security, a smart camera system, after they sold their first tech startup for $500 million in 2017. Athena’s software detects 900 different types of guns and can send an alert and video feed to law enforcement if it senses a threatening movement, like someone pointing a gun, according to Ciabarra. More than 40 schools, malls and businesses in the U.S. use Athena’s software, which charges $100 a month for each camera it monitors. Since schools and malls typically have 100 cameras building-wide, Athena could make more than $100,000 a year monitoring just one school. The weapons detection program has been installed in one of the two New Zealand mosques where a suspected white supremacist opened fire in March, killing 51 worshippers. After the massacre, New Zealand’s prime minister banned assault weapons. But that’s not likely to happen in the United States, says Ciabarra. Even presidential candidates during the fourth Democratic debate Tuesday night couldn’t seem to agree on how to manage assault weapons. Rep. Beto O’Rourke and South Bend, Ind. Mayor Pete Buttigieg clashed on the best way to get the weapons off the streets, whether by banning the sale of assault weapons or also instating mandatory buyback programs.

“We’re not going to change the law and forbid guns. It’s not going to happen,” Ciabarra says. “People will have weapons.”

When Mike Lahiff, a former Navy Seal, launched ZeroEyes, a competing gun-detection system based in Philadelphia, he and his team of fellow veterans saw it as a continued service to the country. Lahiff, a 38-year-old father of four, hopes the U.S. will find a way to reduce gun violence and put him out of business. “If the active shooter problem goes away, and that’s the end of the company, then great,” he says, “that’s a win for me.”

***

While mass tragedies spark surges in sales, most of the bulletproof products on the market today, including backpacks and hoodies, would not withstand the force of the assault-style weapons commonly used in high-casualty attacks. Killers used assault-style weapons in the Sandy Hook and Parkland school shootings, as well as in El Paso and Dayton. The products would, however, protect against most handguns—the weapon of choice in the majority of U.S. gun murders in 2018, according to newly released FBI data. Handguns were used in nearly 65% of the roughly 10,000 gun murders that year, while rifles were used in about 3% of the cases, statistics show.

But spending hundreds of dollars on a hoodie or backpack is not a viable option for many people, particularly those living in lower-income neighborhoods plagued by gun violence. In St. Louis, for example—which has the highest murder rate among major cities in the nation, according to FBI data—more than 65,000 people are living below poverty, and the median household income is about $44,000, according to estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau. Even across the nation, many Americans are not prepared to handle a sudden expense of $400 or more, like replacing a broken car engine or visiting an emergency room without insurance, according to a recent report by the Federal Reserve. Nearly 30% would have to borrow or sell something to pay for the expense, and 12% would not be able to cover the expense at all, the report says.

Bulletproof products may make consumers feel safer, but they may be putting people in more danger, according to school safety experts like Michael Dorn, a former police chief for the Bibb County School District in Georgia who’s now the executive director of Safe Havens International, a nonprofit that advises schools on security. Dorn worries that in a shooting situation, students with bulletproof backpacks may expose themselves to greater risk by standing in place and holding up their packs for protection instead of running away. “A focus on the armor could result in death because people don’t focus instead on things they need to do like lock a door,” says Dorn.

The products may also be distracting officials and parents from focusing on long-term solutions to gun violence, like adequate training and stronger gun laws, critics say. School districts investing in these products are doing so, in many cases, knowing they’re not real fixes, according to Ken Trump, a school safety expert and president of the consulting firm National School Safety and Security Services. “They rely on the hardware, the technology, the gadgets, so they can focus less on the human side,” he says.

Researchers have found some evidence that so-called red flag laws, which allow courts to take guns away from potentially dangerous people, may help stop mass shootings. A recent study by the University of California Davis School of Medicine cited 21 cases in which such a law in California was used to help prevent potential mass shootings in the state. The measure exists in 16 other states and Washington, D.C.

Rather than buy body armor or conduct active shooter training drills, school officials and parents should focus more on early intervention strategies, including student-threat assessments and better student supervision, according to gun control advocates and safety experts. Dorn, who has an 11-year-old son, says he wouldn’t let his child carry a bulletproof product to school, even if it was free. “I teach him how to be alert and react rather than rely on something that’s so statistically unlikely to do any good,” he says.

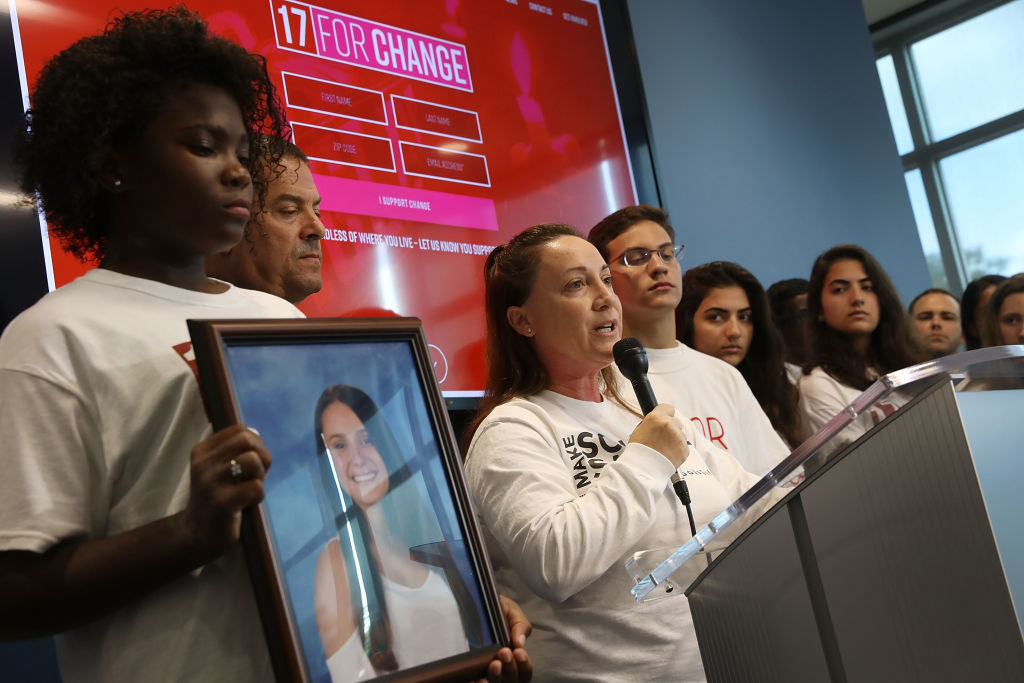

Alhadeff knows the backpacks she bought for her sons are only the last layer of protection. To improve safety in other ways, she launched a national nonprofit, Make Our Schools Safe, and won a seat on the local school board, where she’s pushed for legislation to make schools safer. In February, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy enacted “Alyssa’s Law,” named for Alhadeff’s daughter, which requires every public elementary and secondary school in the state to install a silent panic alarm button. When pressed, the alarm would immediately alert local law enforcement, reducing emergency response times. On Oct. 4, a bipartisan version of the bill was introduced in Congress.

“Before the shooting, my biggest fear was whether my children would do well on their tests,” Alhadeff says. “It’s sad and unfortunate that our society has come to this.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com