Even before the President-elect finally began getting the daily briefing from U.S. intelligence services on Nov. 30, Joe Biden would start his day at his home outside Wilmington, Del., with a two-page rundown on the world. The document was prepared by his own foreign policy and intelligence experts, who several times a week also provide a focused brief on one area of a globe already familiar to the former Vice President and chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. But an additional benefit of the sessions, with longtime advisers like incoming National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan and Secretary of State—designee Antony Blinken, was that they felt almost … normal.

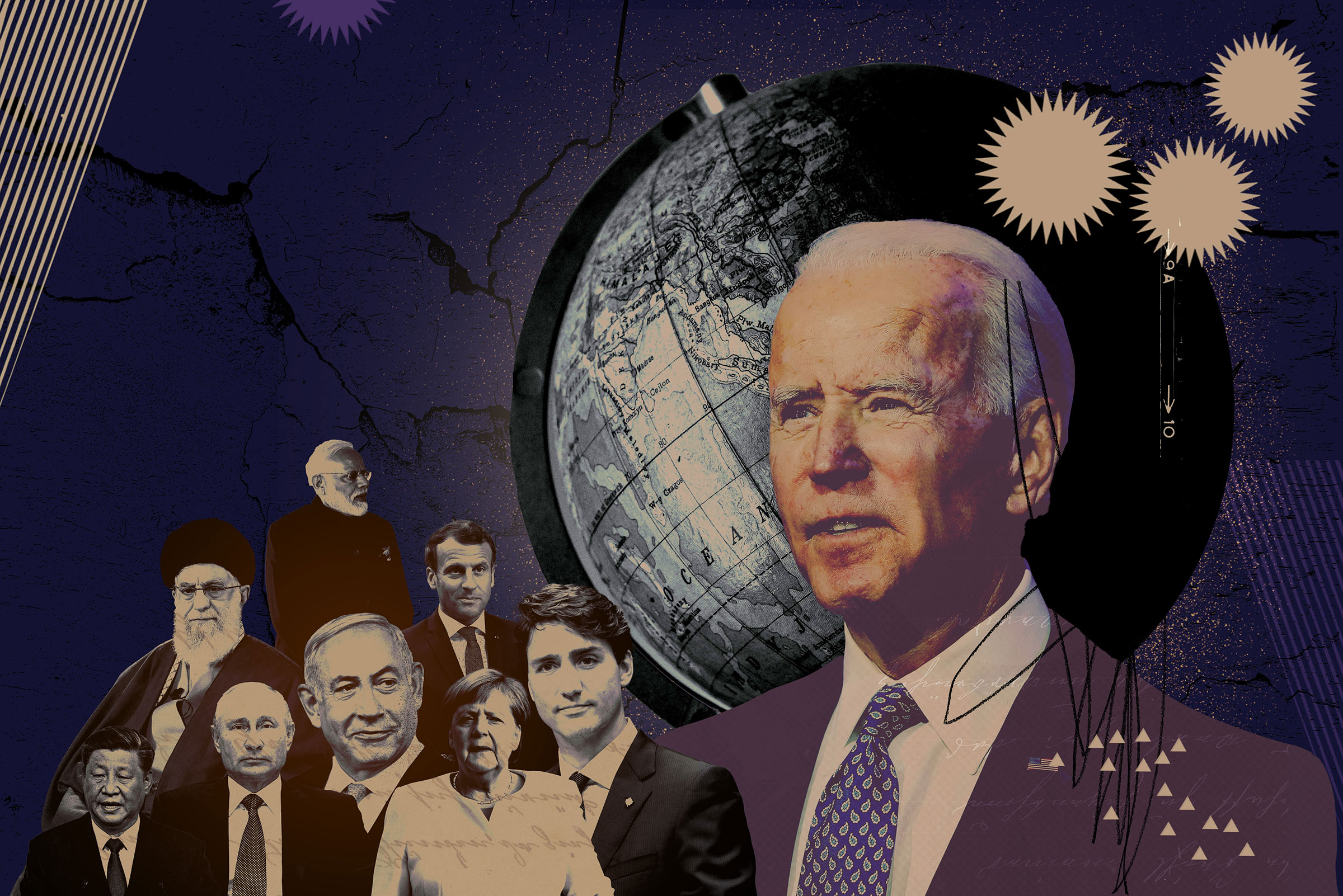

Which is what much of America and the world is craving. For many worn out by President Donald Trump’s disruptions, Biden’s taking the helm of U.S. foreign policy raises the reassuring prospect that the world might go back to the way it was. Even Republican graybeards who have worked with Biden—and Blinken and Sullivan—quietly say they hope for a return to good order on the foreign front. Among America’s allies overseas, the response to Biden’s election “was the collective breathing of a huge sigh of relief,” says former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. “You could sense the unknotting of shoulders all the way from Seoul to Sydney.” Biden himself sounded a reassuring note when he took the podium in Wilmington on Nov. 24 and declared, “America is back.”

But the truth is harder. Biden and his foreign counterparts know the world can’t go back to the way it was. Relations with China are at a half-century low. The NATO alliance is weaker than it has ever been. North Korea, which Trump alternately threatened and wooed, is now the long-range-missile-wielding, self-declared nuclear power that decades of American Presidents sought to prevent. On top of it all, Biden is taking the reins as the world struggles with a global pandemic, the economic, social and political fallout of which remains unclear.

If the world Trump leaves behind poses an enormous challenge for Biden, though, it also presents an opportunity. In fact, Biden inherits the greatest chance to remake American foreign policy since at least 9/11 and perhaps since the end of the Cold War. From the ashes of Trump’s norm-torching “America first” presidency, multiple Biden aides say, there’s a chance to reinvent America’s approach to problems that have long vexed multiple Administrations. In conversations with TIME, the aides say they have a policy blueprint for Biden’s first 100 days, the next 100 days and beyond, that fixes what they can and makes the most of what they can’t.

The immediate strategy, Sullivan tells TIME, “starts with renewal at home and builds to reinvesting in alliances and rejoining institutions.” On the first day of Biden’s presidency, Sullivan says, the U.S. will rejoin the Paris climate accord and the World Health Organization. Then the U.S. will focus on getting a handle on the pandemic at home, in hopes of showing that the once global superpower can get its own house in order. The core of the strategy thereafter, Sullivan says, is to rally allies that represent “half the world’s economy” to address common challenges like China, North Korea, Russia or Middle East instability.

How to do that is where the real challenge of remaking American foreign policy for the post-Trump era begins.

Biden’s team has had a surreal start, denied transition briefings for two weeks because of the incumbent’s refusal to acknowledge the election results and the need to convene remotely during the pandemic. “We’ve had to work together with people we’ve never met together in person,” says Julie Smith, Biden’s former Deputy National Security Adviser who’s now with the transition team. “I don’t know how tall anybody is. I don’t know how short anybody is. All I’ve seen is their kitchen.”

In some ways that’s appropriate: America’s new start abroad must begin at home, Biden’s aides say. In his attempt to deal a death blow to what he termed the “deep state,” Trump axed or left unfilled hundreds of positions at the State Department, the Defense Department and other agencies and cut the National Security Council (NSC) staff in half. He eliminated, shrank or downgraded entire offices, like the NSC’s pandemic cell, which Sullivan intends to rebuild. Dozens of ambassador posts remain vacant.

Rebuilding offers Biden the chance to remake a famously calcified foreign policy bureaucracy. “We’re going in with a bit of a clean slate in these institutions, because the damage is so severe,” says Smith. “We obviously have to build back the workforce,” she says, but they can also revamp structures that were designed “70-plus years ago.”

Conversations with Biden’s staffers summon the same sense of regret and opportunity abroad. In China, the Middle East and Europe, Trump upended foreign policy dilemmas that had hamstrung the U.S. and its allies for decades. For years American diplomats struggled to figure out how to stop China from cheating on international rules of commerce without starting a trade war, how to make peace between Arabs and Israelis without selling out the Palestinians, and how to get Europe to shoulder the costs of its own defense without weakening the nation’s alliance with them.

In each case, Trump blew the problem up with no long-term solution and at real cost: America is in an expensive trade war with China, the two-state solution to Israeli-Palestinian conflict is moribund, and NATO is struggling. But each case also now offers Biden a chance to reframe the problem, and perhaps approach it with a new, more effective strategy.

The knock on Biden, and his team, is that they won’t seize the opportunity, but through a combination of reflex and inertia will seek to revert to past policies despite all the change in the world. “I know some of these folks. They took a very different view,” Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said Nov. 24 on Fox News. “They led from behind; they appeased. I hope they will choose a different course.”

And it’s not clear what strategies, beyond alliance building, can work. Gérard Araud, a former French ambassador to the U.S., U.N. and Israel, has worked with many members of the incoming Biden team as far back as the Clinton Administration. He predicts they’ll be challenged—and likely chastened—by “the new balance of power” set by China’s rising economic and military strength and Russia’s growing adventurism, which has handed Moscow the upper hand in places like Syria, Ukraine and Libya. America’s rising isolationism after years of foreign entanglements will make building consensus at home hard too. Trump’s withdrawal from the world builds on “the inheritance of Obama, who didn’t go to Ukraine, who didn’t go to Syria,” Araud says, reflecting the wider “fatigue of the Americans towards intervention.”

When it comes to rebuilding at home and abroad, however, Biden brings something many are desperate for: empathy. On a trip to Brazil back in 2013, then Vice President Biden noticed a blue star on the lapel of then Ambassador Thomas Shannon Jr., who greeted him on the windy tarmac in Rio. That small symbol linked Biden and Shannon as parents of children serving in war zones, and Shannon explained that his son was serving in Afghanistan. Days later, as he boarded Air Force Two for home, Biden doubled back, dug into his pocket and handed Shannon, a practicing Catholic, a thumb-size silver rosary, saying, “This got Beau safely out of Iraq. I hope it gets your son out of Afghanistan.”

Such moments matter in diplomacy, especially now as America tries to rebuild its reputation as a global leader while withdrawing in both Afghanistan and Iraq. Just as important, though, is experience. Even some of Biden’s political opponents say that is his strongest suit. Ambassador James Jeffrey, Trump’s former Syria envoy who retired in November, calls the incoming team “highly capable, competent patriots” of the “Kissingerian school” who will act in the interest of keeping America safe rather than hewing to a particular ideology. Biden, he says, is a “natural, if blunt, diplomat” who was unflappable under rocket fire that hit the U.S. embassy compound in Baghdad in 2010 during one of the then Vice President’s visits to the Iraqi capital. “I’ve never seen anybody as calm,” he recalls.

For his part, Biden seems to appreciate the opportunity he’s been handed. Introducing his foreign policy team on Nov. 24, the President-elect declared, “We cannot meet these challenges with old thinking and unchanged habits.”

NATO, Russia and Europe

Rebuilding alliances may be central to Biden’s global strategy, but in Europe, as elsewhere, the world has changed. German Chancellor Angela Merkel left her first meeting with Trump convinced that Europeans had to start taking care of themselves, recalls the State Department’s former No. 3, Ambassador Thomas Shannon. Trump’s assault on the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and especially Article 5 of its charter, which pledges that an attack on one nation is an attack on them all, undermined faith that Europe and the U.S. would stand together against common enemies.

Over the ensuing four years, European allies have upped their defense spending, and that’s not a bad thing: U.S. complaints that Europe underfunds its own defense go back decades. France, moreover, has boosted its counterterrorism presence in Africa, to the relief of U.S. commanders there.

But European burden-sharing has come at a cost. None was more pleased by Trump’s moves than Russian strongman Vladimir Putin, whose revanchist agenda in Ukraine and elsewhere in Eastern Europe has challenged the West. As NATO weakened, Putin insinuated Russia into European politics, supporting Moscow-friendly candidates with a mixture of money and disinformation.

Heavy U.S. sanctions and an opening on nuclear-weapons diplomacy give the Biden team a chance to reset relations with Moscow. The New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or New START, expires Feb. 5, 2021. If it sunsets, it will be the first time in the effort to limit the nuclear stockpiles in the U.S. and Russia since 1972. Moscow has hinted it may be ready to deal.

At the same time, Biden has moved to restore faith in NATO in calls with Merkel, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and French President Emmanuel Macron. “They know that he wants to revitalize alliances,” says Julie Smith, of Biden’s foreign policy team. “They’re counting on him to do that.” —W.J. Hennigan and Kimberly Dozier

The Price, and Potential, of a Separate Peace

Trump fundamentally changed the game in the Middle East. He cut off aid to the Palestinians, embraced an Israeli plan to take control of most Palestinian territory and recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. At the same time, Trump wooed Gulf states by getting tough on Iran. The gambit yielded the Abraham Accords—the United Arab Emirates’ recognition of Israel in return for halting the threatened seizure of West Bank territory. Bahrain and Sudan followed by normalizing relations with the Jewish state.

Those moves came at a price, all but killing the long-sought “two state” solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The incoming Administration recognizes putting peace talks between Israelis and Palestinians back on track will be hard. Biden says he won’t reverse the Trump Administration’s moves on Jerusalem, but beyond that, his incoming team’s goals seem modest: reaching out to both sides to “just try to preserve the possibility of a two-state solution, [and] not allow for further erosion or deterioration,” Biden’s incoming National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan says.

Biden has plenty on his hands nearby, dealing with Iran, which already turned up the heat by again expanding its nuclear program and now threatening to bar inspectors if U.S. sanctions aren’t lifted by February. Nevertheless, Tehran indicated its willingness to talk to the Biden team. Sullivan signaled openness to lifting sanctions to salvage the 2015 agreement, adding, “We have proven to Iran over time that we can put sanctions back on after they have been relaxed in ways that create enormous economic pressure.” —K.D. and W.J.H.

Remaking the Rules for China

For years, Beijing rewarded attempts to welcome it into the global, rules-based order by building military bases in the South China Sea and, according to Washington, cyberstealing U.S. technology and U.S. government personnel records, and cyberattacking the Pentagon. The disappointments continued during Trump’s term, with China effectively ending Hong Kong’s autonomy decades early and expanding its crackdown on minorities like the Uighurs.

Trump’s team waged solo economic war, slapping on tariffs, sanctioning Chinese officials and labeling companies like Huawei and TikTok as national-security threats, all to limited effect. China is now one of the biggest traders, funders, infrastructure builders and preferred lenders in Africa, Latin America, and Central and Southeast Asia. In November it minted a 15-country free-trade alliance, the world’s largest, that includes Australia and New Zealand.

Trump negotiated a bilateral trade deal that threatens more tariffs if China doesn’t buy $200 billion in U.S. goods and services over the next two years, which hands Biden some leverage. But Trump’s attendant China-bashing has helped fuel historically high anti-China sentiment among Americans, making future compromise with Beijing harder politically.

Biden is looking for a new approach on China: after a 2011 visit he declared that “a rising China is a positive, positive development, not only for China but for America and the world writ large.” Now his team will spend its opening months rounding up a hands-across-the-water mix of democratically minded Pacific and European allies to check China’s expansionism. The size of their combined markets—more than half the world’s economy— will lay down “a marker that says, if you continue to abuse the system in the following ways, there will be consequences,” says Biden’s incoming National Security Adviser, Jake Sullivan.

That will require undoing some of the damage of the past few years, to offset China’s growing regional influence without devolving into conflict. “If we invest in ourselves, invest in our relationships with our allies, and play this key role in international institutions,” Sullivan says, “there is no reason why we cannot effectively manage the China challenge in a way that avoids the downward spiral into confrontation.” —K.D. and W.J.H./Washington and Charlie Campbell/Beijing

North Korea, Going South

Not all of Trump’s broken foreign policy pottery can be mended. North Korea is more isolated, desperate and dangerous today than it has ever been. The U.S. estimates the North has enough nuclear material for two dozen or more weapons and long-range missiles that can reach the continental U.S. The pressures of international sanctions, natural disasters and the coronavirus pandemic have worsened living conditions for regular citizens and prodded the authoritarian government to engage diplomatically with outside nations. But Trump’s strategy of flattery and face-to-face summits led to no disarmament, and official U.S.—North Korea talks stalled last year.

Every U.S. President for 30 years has tried to avoid this destabilizing situation, but there is no going back now. Biden must try to improve Washington’s frayed relations with regional allies South Korea and Japan, and collectively apply pressure to get Pyongyang back to the negotiating table. Trump made that harder, depicting South Korea and Japan as free riders and demanding billions of dollars to pay for the 80,000 U.S. troops in the two countries.

The incoming Administration will start building a plan with Seoul and Tokyo before approaching Pyongyang, Biden’s aides say. “What you’ll see is much more of a united front,” says Colin Kahl, who served as Biden’s National Security Adviser from October 2014 to January 2017 and now works on his transition team. “Making real progress on these issues in the medium to long term is exponentially greater if we’re working alongside our allies, but also managing our allies’ relations with one another.” —W.J.H. and K.D./Washington and Steven Borowiec/Seoul

With reporting by Charlie Campbell/Beijing and Leslie Dickstein and Simmone Shah/New York

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to W.J. Hennigan at william.hennigan@time.com