One of the biggest challenges of this unsettling time is the isolation we feel as we’re separated from friends and family, all the people for whom we care most deeply. But just being alone is only part of the difficulty. Our sense of remoteness is intensified by a pall of unease we can’t define: Loss and sorrow are also in the air. We fear losing—or we may have already lost—people we love. And when we work up the courage to look beyond our individual personal spheres, we see that many people who have made our world better, in big and small ways, have vanished before we were ready to let them go.

But not even sorrow is one-dimensional. There can always be at least a glimmer of joy in remembering things that people gave us while they were here. In his jubilant and revivifying memoir, I Remember, the artist and writer Joe Brainard tabulated all the little things that can come to shape how we think about life. It’s a book of large truths disguised as small ones: “I remember,” he writes, “those times of not knowing if you feel really happy or really sad. (Wet eyes and a high heart.)”

We have no roadmap for this new territory. But we all, at one time or another, have reason to mourn. Maybe we can be better at celebrating life even as we’re saddened by its loss. That’s the goal of this list: to acknowledge the remarkable and joyful lives of some of those we have lost. It’s not comprehensive, nor is it meant to be. These are just some of the people who have been taken from us, even as they have left us much to remember them by. Let’s think of them with wet eyes and a high heart. —Stephanie Zacharek

Romi Aneja

This Mother’s Day, my mom was sedated and on a ventilator. On a day when we would usually shower her with gifts and take her out to lunch, my family huddled around our phones and tablets as the nurse showed her to us over video chat. All we could do for the mom who gave us everything is tell her how much we loved her and hope that somehow, she could hear us.

Nine days later she lost her battle to COVID-19. She was 64. My mom had also been fighting rheumatoid arthritis for many years. This meant she was immunocompromised and part of a population that is especially vulnerable to this disease. But though her hands and joints would flare up periodically, nothing would stop her from making her children’s favorite foods when they visited or hugging and holding her granddaughter tight.

She was a bright light in her community. She loved to laugh, joke and get together with her many friends. My mom was one of those people that just drew others to her. Wherever she went she made friends, and she never neglected to keep in touch with them.

As a wife and mother, she had endless love for us. One of the most important things a mother can do is pass on her best traits. I can only hope that the kindness, compassion and generosity she has shown us over the years remains with us as we mourn her passing and celebrate her life. —Arpita Aneja

——-

Arpita Aneja is a video producer for TIME

Mary Agyeiwaa Agyapong

Firefighters and hospital staff at the Luton and Dunstable University Hospital in Luton, England held a minute of silence on April 16, after 28-year-old Mary Agyeiwaa Agyapong—a pregnant nurse who worked at the hospital—died of COVID-19 while her baby was saved.

Agyapong, who also went by her married name, Mary Boateng, tested positive for COVID-19 on April 5 and was hospitalized two days later. Agyapong underwent an emergency C-section shortly after she was admitted, and gave birth to a baby girl. The new mother died on April 12.

Her daugher, who was named Mary in memory of her mother, is “doing very well” according to hospital officials. Agyapong’s husband is currently self-isolating and has been tested for COVID-19.

“Mary worked here for five years and was a highly valued and loved member of our team, a fantastic nurse and a great example of what we stand for in this Trust,” David Carter, CEO of Bedfordshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, said in a statement.

Agyapong completed her last shift on March 12 and had not returned to work in the subsequent weeks. While working, she had not been treating COVID-19 patients. It is unclear where Ms. Agyapong contracted the virus and whether she had any pre-existing medical conditions that put her at higher risk

Since her passing, a GoFundMe page for Agyapong’s family and newborn child has raised more than $200,000 by April 17. The campaign creator, Rhoda Asiedu, wrote “it is humane for us to take care of them in every way we can during this heavy and trying time.” She added, “we will forever miss you.” —Melissa Godin

Marylou Armer

On April 3, police officers from across Northern California solemnly lined up their vehicles to honor Marylou Armer, a police detective in Santa Rosa who is the first known law enforcement officer in the state to die of complications from the coronavirus. As a helicopter whirred above, a line of black-and-whites stretching to the horizon traveled more than 50 miles, escorting a hearse that drove her body from a hospital in Vallejo to a cemetery in Napa.

“Marylou made a difference, as a detective and as a person,” Santa Rosa Police Chief Rainer Navarro told the Sonoma Index-Tribune. “She exude[d] the professionalism and the character that I think every person in our department carries.”

Law enforcement officers throughout the country have been struck by the virus, as they have continued to go to work amid the pandemic. Acknowledging these circumstances, local officials described Armer’s death as occurring in the line of duty. The detective tested positive for COVID-19 in early March and died on March 31, leaving behind her husband and daughter. She was 43.

“Marylou was a bright light in this organization,” Navarro said in a video statement. “Marylou was always proactive and there with a smile. She was a thoughtful and committed public servant who loved helping people and loved the people she worked with.”

Armer began with the department as a field evidence technician in 1999 and went on to become a sworn officer in 2008. Her latest assignment was working for the city’s domestic violence and sexual assault team.

She grew up in the San Diego area, where she took part in a police department explorer program as a teenager. A fellow explorer, Alejandra Sotelo-Solis, now the mayor of National City, Calif., recalled Armer as one of few young women of color who took on a leadership role in the program. In a Facebook post, she described Armer as a “true role model” and reminded her constituents to, please, stay home.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom also praised Armer in a public statement, and ordered Capitol flags flown at half-staff in her honor. “Amid the current fight against COVID-19, Detective Armer selflessly and courageously served her community and the people of California,” he said. “We extend our heartfelt condolences to her family, friends, colleagues and members of the Santa Rosa community as they mourn her loss.” —Katy Steinmetz

Tawauna Averette

Tawauna Averette died without ever being able to hold her baby daughter in her arms.

Averette, a nurse with Kettering Health Network in Ohio, was first sickened by COVID-19 at the end of October while she was pregnant with her seventh child, according to the Dayton Daily News. Although she was initially hospitalized and released, Averette’s symptoms worsened and she was readmitted just one day after coming home.

The veteran mom gave birth to her daughter, named Skye, in the ICU via C-section six weeks early due to health concerns, per the outlet. It was the only time Averette was able to see her daughter in person. Averette died on Dec. 8 of complications related to the coronavirus. She was 42.

“She got to Facetime with [Skye] while she was in the hospital, but that was very, very, hard for her,” her husband of 14 years, Charles Averette, told the Daily News. Although the baby is home and doing well, Charles said the family is devastated over the loss of their matriarch. “It’s hard. She was everything for us, and we don’t have her no more.”

Kelly Albes-Fisher, who described herself as Averette’s longtime friend in an interview with the Daily News, said that Averette was a hardworking person who often juggled two to three jobs. She was a dedicated mom and Cincinnati Bengals fan who also was very political and loved to debate.

Averette shared her COVID-19 health struggles on Facebook while she was hospitalized, and spoke candidly about the loneliness and fear she felt about the virus and being separated from her family. She also reminded her followers to stay safe. “Y’all know I have been an advocate for safety and precautions for Covid since it first came out,” she said in a Nov. 9 update. “All I did was go to work and come home…please get tested and make sure you know who you are around…wear masks and please please wash your hands!!!!!!!” —Kathy Ehrich Dowd

Peyton Baumgarth

Like many eighth graders across America, Peyton Baumgarth loved making YouTube videos, playing Pokémon GO and spending time with his family. On Halloween, Peyton’s young life was cut short after he died of complications related to the coronavirus. He was 13.

“Peyton was a wonderful young man, who always had a smile to share with you. He was so very sweet and caring and FUN,” Mary Payne, who describes herself as Peyton’s mother’s best friend, wrote in a GoFundMe she set up for his family after his death. “This is a devastating loss that leaves a tremendous hole in the heart of every person that knew Peyton.”

Peyton was the first person under age 18 to die of complications related to the coronavirus in the state of Missouri, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, citing state health data. His mother, Stephanie Franek, told News 4 in Missouri that she tested positive for COVID-19 on Oct. 26 and that Peyton began showing his own symptoms of the virus a short time later.

Dr. Lori VanLeer, superintendent of Peyton’s school district, said in a letter to parents after his death that his family “asks that we all remember to wear masks, wash hands frequently and follow guidelines. COVID-19 is real and they want to remind students and parents to take these precautions in and outside of school.”

“This is just something that no parent should ever have to do,” Franek also told News 4 of her son’s passing. “I don’t even know how to take a breath, let alone get through the next days and weeks and months and years without him.” —Kathy Ehrich Dowd

Aileen Baviera

Aileen Baviera was a professor, a government analyst, the head of an NGO and a public speaker. But she will be remembered as an expert who studied China for the sake of her home—the Philippines.

Baviera got her start as one of the Philippines’ foremost China watchers in 1979, when she began her graduate studies at the University of the Philippines, specializing in contemporary China. Later, she became one of the first researchers to receive a Chinese government scholarship to spend two years as a foreign student in Beijing. She also worked part-time at the Chicago Tribune’s Beijing bureau, compiling clips of Western media reports on China.

In 1980, she returned to the Philippines and worked as a government researcher at the Department of Foreign Affairs. From there, she ventured back into academia, teaching at Ateneo de Manila University and the University of the Philippines, where she earned a Ph.D. in political science in 2003. She then served as dean of the university’s Asian Center from 2003 to 2009. Her colleagues and students remember her for her balanced insight on Philippines-China relations and influential ideas about the social and economic issues common to the two developing countries.

“She shared her network with us her students and was responsible for making the study of international relations in the Philippines accessible to as many people as possible,” Ederson Delos Trino Tapia, one of Baviera’s former students, says. He is now a public administration professor and dean at the College of Continuing, Advanced and Professional Studies at the University of Makati in Manila. “I will never forget Aileen’s impact on my life as a young international relations student.”

Baviera died at age 60 on March 23 at the San Lavaro Hospital in Manila after contracting the coronavirus. She had attended an academic conference in Paris where one participant was diagnosed with COVID-19, her university said.

She was founding president of the Asia Pacific Pathways to Progress, an NGO that promotes peace and cultural understanding through international dialogue and cooperation.

“She was an exacting but generous mentor to the next generation of social scientists and strategic thinkers in the country and in Southeast Asia,” the organization wrote in a Facebook post. “She was a dear friend and an exceptional individual.” —Hillary Leung

Gianmarco Bertolotti

Gianmarco Bertolotti was my baby brother and my best friend. He was only 42 years old and worked for Lenox Hill Hospital as a mason in the healthcare union and was an essential worker. He was admitted to Mount Sinai hospital after visiting an urgent care – he was told he had a double lung infection. One week later, my heart was forever broken as my beautiful brother passed away from COVID-19.

Gianmarco loved deeply, smiled often and had no enemies. He loved the city of New Orleans, his father’s cooking and his self-renovated apartment in Astoria, Queens. He was unique and pure and a really good listener. He was adventurous, from trying new (often pretty disgusting) delicacies to exploring new cities and locales. Some of my happiest memories involve him singing and dancing, full of life and love. He was good with his hands and created breathtaking art. I remember how Gianmarco would run to my grandmother, holding her hand and offering support for her to walk—he at 6′ 2,” her less than 5′.

He had friends that he just met and ones he’d known over 35 years. Since his passing, I’ve discovered that so many people loved my brother just as much as I did. He didn’t judge, was laid back and music truly moved his soul. He loved a good debate, was loyal and loved his family with all his heart.

Gianmarco loved to read and learning excited him. He was diverse in his interests and just a really good dude. Since we’d lost our mother 6 years ago and our grandmother 2 years ago, my father, Gianmarco and I had been a team, one that is now forever broken. I’ve learned that Gianmarco had a special way about him that forged a lasting bond with everyone he met. His impact was profound and I’m devastated knowing that such a sweet soul was truly meant for so much more. —Monique Bertolotti

———-

Monique Bertolotti is Gianmarco’s sister.

Rafael Leonardo Black

It was not uncommon to see figures as disparate as Andy Warhol, Adam and Eve, Latin American dictators and giraffes all sharing space in one of Rafael Leonardo Black’s drawings. The artist populated his work with characters from history and myth alike, creating surrealist, hyper-detailed tapestries that challenged any linear or conventional Western approach to history.

After creating these works mostly for himself and friends for decades, Black broke out in 2013 at age 64, when he was invited to put on his debut solo show, which was met with acclaim. Black was still working diligently on his art in the weeks before his death on May 15 from complications related to the coronavirus, which was compounded by an ongoing battle with diabetes. He was 71.

“When he opened his mouth, art came out,” says Rose Murphy, Black’s longtime friend and the wife of his nephew Jean.

Black was born in Aruba on January 6, 1949, and moved to the U.S. with his sister when he was 17. He majored in art history at Columbia and immersed himself in the local art and music scenes during a countercultural explosion, going to galleries every Saturday morning and seeing young talents like Jimi Hendrix and David Bowie at local venues at night.

As a classmate, he was incredibly intellectually curious and well-read. “He had a photographic memory about things,” says Tej Hazarika, a college friend. “He was so scholarly and always wanted to go deeper into topics.”

Black dropped out in 1970. For the rest of his life, he would live a minimal, solitary lifestyle and take on odd jobs to pay the bills. When he wasn’t working for money, he was pouring himself into his artwork. His specialty medium was lead pencils, which he would sharpen by hand with an X-acto knife.

His work was often minuscule and teemed with real and fictional characters and artistic artifacts: Duchamp’s urinal hanging next to the head of Coco Chanel; surrealist André Breton next to actor Buster Keaton. The artworks were so dense and detailed that at his 2013 show, each piece of art was accompanied by a magnifying glass and a guide with labels and annotations. “Each composition is like a symphony or a novel,” Hazarika says. “They were powerful slices of myth and reality.”

If Black was pleasantly surprised by his late-career success, he wasn’t expecting or even hoping for it. “He wasn’t interested in the money, the fame or fortune,” Murphy said. “I don’t think he ever thought about selling his art. He just did it.” —Andrew R. Chow

Lillian Blancas

Lillian Elena Blancas’s long-held dream of becoming a judge was realized on Dec. 12 when she won a runoff election for a position on Municipal Court 4 in El Paso, Texas. But Blancas will not be able to fulfill the role she fought so hard to secure to serve the community she loved. Her victory came five days after her death of COVID-19. She was 47.

“She was an amazing human being, a dedicated public servant, and a tireless advocate for her clients and our community,” close friend Amanda Enriquez, a local Assistant District Attorney, told the El Paso Times. “Her personality and laughter filled up every room she entered and she was the most selfless friend I could have ever asked for. I will miss her so very much.”

According to local news outlets, Blancas was hospitalized for the second time on Nov. 9 after she was first diagnosed with COVID-19 in October.

Blancas had more than 10 years of experience as a lawyer in El Paso, where she was born and raised by immigrant parents from Mexico. Throughout her career, she served as a part-time criminal law magistrate, public defender, an assistant district attorney and was a mentor to aspiring criminal defense attorneys who wanted to represent low-income people, according to a Q&A with Blancas and the Times earlier this year. She also just opened her own law practice in 2019.

“She was brilliant, hilarious, kind and generous. And she was one of those attorneys that you would go to if you had questions about the law or about how to handle a case correctly,” attorney Heather Hall told El Paso Matters.

Blancas won the initial election for the municipal judgeship on Nov. 3, but did not earn the 50% of the vote needed to avoid the Dec. 12 runoff. The El Paso City Council will now have to vote to appoint a judge in Blancas’ place, according to local news outlets.

Blancas was already sickened by COVID-19 after her initial victory, but was still able to express her desire to secure the position she passionately believed could make a difference in the lives of others.

“Thank you to each and every El Pasoan that voted for me. I am extremely humbled and grateful for your support,” Blancas wrote on her campaign’s Facebook page on Nov. 4. “My work is not yet done.” —Jasmine Aguilera

John Bompengo

Congolese photographer and video journalist John Bompengo dedicated his life to covering some of the most tumultuous events in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s recent history, from political uprisings to ethnic violence and Ebola outbreaks.

Unflappable in the face of danger, and always ready to crack a joke, Bompengo finally encountered a situation he couldn’t talk his way out of: COVID-19. On June 20, he died of complications from the disease in Kinshasa, after spending a week under hospital care. He was 52 and is survived by his wife and nine children.

Bompengo, a 16-year veteran of the Associated Press and a frequent producer for the UN-backed news service Radio Okapi, was a multi-talented journalist who easily shifted from radio to print to video as the situation demanded. He was a regular presence at any news event, and was always willing to share advice and resources with his fellow journalists, particularly those just getting started. Many consider him a mentor.

“Before Bompengo, being a photographer in DRC was not considered a respectable job,” says video producer Adolph Basengezi, who adds that glimpsing Bompengo’s byline on a photograph in an international newspaper inspired him to go into journalism. “We used to think that to be a good photographer, you had to be a Westerner. Bompengo showed the world that we can do the work as well, that the DRC has good people and talent too.” —Aryn Baker

María Teresa de Borbón-Parma

Despite being a descendent of Spanish royalty, María Teresa de Borbón-Parma made a name for herself in her own right, forging a career as an academic and political activist.

After studying at the Sorbonne in Paris, she reportedly served as a professor there and at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, and developed a reputation as an outspoken socialist and a defender of women’s rights. For her views, historian Josep Carles Clemente dubbed her “The Red Princess” and described her “vehement defense of the most needy and of democracy.”

As the daughter of Francisco Javier de Borbón-Parma, a member of a cadet branch of the Spanish royal family, she also carried on her heritage by supporting Carlism, which advocates an alternative succession for the Spanish throne. Members of the Carlist movement claimed that Francisco Javier was the legitimate Spanish ruler, and he laid claim to the Spanish crown in 1952, although he was not widely recognized as Spain’s ruler.

Her brother, Sixto Enrique de Borbón, said she died at age 86 in Paris from COVID-19, in a message posted on Facebook on March 26.

“Don Sixto Enrique is saddened, and asks you to pray for his sister’s eternal rest,” the message said, according to a TIME translation from the original Spanish.

A funeral service was held for her in Paris, where she was born. —Tara Law

Lorena Borjas

When the coronavirus crisis infiltrated her beloved New York City, Lorena Borjas sprang to action like she always did. In mid-March, the pillar of the city’s trans Latinx community set up a fund to help trans people who had lost their jobs to COVID-19. Yet on March 30, Borjas, 59, lost her own life to complications from the virus.

“Lorena was like a mother for many in the transgender community,” Bianey Garcia, one of many people aided by Borjas over the years, tells TIME. “She used to help anyone.“

Borjas had been a prominent community organizer and health educator for decades, working to end human trafficking, which she herself survived, according to the Transgender Law Center.

Her community health work included an HIV testing site Borjas set up in her own home, and a syringe exchange program for trans women using hormone injections. In 2012, she and activist Chase Strangio co-founded the Lorena Borjas Community Fund, which helped cover bail and pay legal fees for LGBTQ immigrants.

Lynly Egyes, 38, legal director of the Transgender Law Center, tells TIME she first met Borjas while working for the Sex Workers Project at the Urban Justice Center. At the time, Egyes remembers she was representing two incarcerated transgender women; Borjas “just showed up” with a much-needed birth certificate for one of the women, pulling it out of the Mary Poppins-style roller bag she always carried with her. “You never knew what was in there,” Egyes laughed.

“She’s made the world better so selflessly, so humbly, without often any type of recognition,” Egyes added. “I think she taught everyone she knew about how to be a better person.” —Madeleine Carlisle

Eve Branson

Announcing the sad news of his mother’s death, Richard Branson said there would not have been a Virgin Group without Eve Branson.

Describing her as “a force of nature” in a blog post, the multibillionaire credits his mother with giving him the first £100 he needed as seed money to start his company. And it’s obvious she further served as an impactful role model for the mogul: “When I was growing up she was always working [on] a project; she was inventive, fearless, relentless—an entrepreneur before the word existed,” he wrote.

Although Branson said his mom “lived many remarkable lives,” it was a singular disease that led to her death after she contracted COVID-19. She died on Jan. 8 at age 96.

In a biography that rivals her son’s, Branson described just some of her accomplishments in his post: “She took glider lessons disguised as a boy, enlisted in the WRENS during World War II, toured Germany as a ballet dancer after the war, acted on the West End stage and worked as a pioneering air hostess on the treacherous British South American Airways routes.”

Later, she founded The Eve Branson Foundation in Morocco, aimed at supporting the lives of families and communities in the Atlas Mountain.

A mother to three, a grandmother to 11 and great-grandmother to 10, Branson says his mom was fiercely dedicated to family, and supported them in part through notes of encouragement. “Isn’t life wonderful?” she wrote in a poem to Branson that he shared in his tribute. “Every hour, every minute, must be lived to the full.” —Kathy Ehrich Dowd

Freddie Brown Jr. and Freddie Brown III

On March 26, Sandy Brown lost her 59-year-old husband to the coronavirus. Three days later, she lost her only son, 20, to the same invisible foe. She announced the devastating news on Facebook and offered a prayer, asking that the lives of Freddie Brown Jr., and Freddie Brown III be seen as sufficient sacrifice for the angel of death. “Take no more spouses or children from their families,” the mother pleaded. Their deaths, she said, mean “My entire immediate family is gone!”

The men lived in the Flint, Mich., area, where the younger Brown had played on the football team at Grand Blanc High School, despite suffering from asthma. He graduated in 2018 and, according to his mother, planned to enroll at Michigan State University this fall.

To remember the defensive lineman, the Grand Blanc Bobcats shared a quote on social media, plucked from the 1979 Nobel Peace Prize lecture of Mother Teresa: “Let us always meet each other with a smile, for the smile is the beginning of love.” That, the team said, was Freddie. Clinton Alexander, the team’s head coach, described Brown as “one of the kindest players I have ever had the pleasure to coach.”

Brown, Jr., served as an elder at a local church, which was feeling the loss of both men, as well as a third church member who had succumbed to the coronavirus at the end of March. According to his obituary, Brown Jr., was also an athlete, attending Southern Methodist University on a basketball scholarship. He went on to work as a produce clerk at a shopping center for 32 years. He was a snappy dresser. And, like his son, he also had an enduring habit of greeting people with a smile. —Katy Steinmetz

Araceli Buendia Ilagan

Araceli Buendia Ilagan first registered as a nurse in Florida in 1982 and was there, on the front lines, until the very end.

According to Jackson Memorial Hospital, where she worked in the intensive care unit, she completed a shift in Miami on March 24. Three days later, Buendia Ilagan died due to complications from the coronavirus. She was 63.

On social media, coworkers described her as a mentor, a loyal caretaker and a fount of knowledge. Buendia Ilagan was a 5 ft., 1-in. “giant,” a fellow nurse named Garfield Phillpotts wrote on Facebook. He described her as passionate and protective, as someone who had a knack for knowing other nurses’ patients even better than they did. The veteran healthcare professional “would have been the perfect general to help lead us through this fight.” Instead, he lamented, she was among the first to fall.

According to the Miami Herald, the woman known as “Celi” to friends was the second healthcare worker in South Florida to succumb to COVID-19. The Filipina-American trained at a campus of St. Louis University in the Philippines in the late 1970s, records show, and later studied to become a nurse practitioner at Barry University in Florida.

“Araceli dedicated nearly 33 years of her life treating some of our most critically ill patients,” Jackson Memorial Hospital said in a statement. “During her long and storied career, she also mentored and trained other nurses, and was a champion for the profession.” Buendia Ilagan and others like her, the statement said, are “true heroes.” —Katy Steinmetz

Lisa Burhannan

Even from her hospital bed after contracting the coronavirus, Lisa Burhannan continued to host Zoom meetings and do the hard work that benefitted some of the most vulnerable members of her Harrisburg, Pa. community.

Burhannan dedicated her life to mentoring young women, helping the recently incarcerated transition back to life on the outside and supporting victims of violence, among many other passionate causes. She served as a Harrisburg chapter coordinator for Crime Survivors for Safety and Justice (CSSJ), an organization dedicated to helping victims of violence through their healing process, and was involved with other local and national organizations that helped people in need, including Breaking the Chainz, and Mothers in Charge.

Burhannan died of COVID-19 on June 11. She was 50.

“Already, there’s been a huge void for our work in Pennsylvania,” says Aswad Thomas, CSSJ’s managing director. “I had a moment yesterday where I couldn’t call Lisa, and I struggled a little bit…It’s going to be challenging moving forward without Lisa’s presence.”

CSSJ is now designing an annual award in Burhannan’s name.

Kevin Dolphin, founder of Breaking the Chainz, a nonprofit that runs prevention programs to keep people out of prison, knew Burhannan for 40 years. He describes her as selfless, outgoing, endearingly rough around the edges and one who took a tough-love approach to those she pushed to better themselves. People close to her say she survived domestic violence and lost one of her own children to gun violence.

“Lisa became a first responder in a way,” says Dolphin, who adds that together they would respond to incidents of violence in their neighborhood to comfort family members. “She gave her heart to those who were crime victims.”

“Lisa is the definition of a survivor,” says Thomas. “The definition of a leader in the community and dedicated to making change.” —Jasmine Aguilera

Revall Burke

On March 17, Revall Burke spent his day as a poll worker in the Illinois primary at the Zion Hill Baptist Church in Chicago’s 17th Ward, as he had done so for years. Fifteen days later, on April 1, he passed away from complications related to coronavirus. He was 60.

His death has resurfaced a debate over whether the state should have held its primary, which took place just four days before Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker issued a stay-at-home order to stem the virus’ spread.

At the time, Gov. Pritzker said he did not have legal authority to shut down the election and instead encouraged people to vote by mail. NBC 5 reports that at least four voters or poll workers, including Burke, tested positive for COVID-19 after the primary (although it is not clear when or where they contracted the virus).

A spokesman for the Chicago Board of Elections Commissioners tells TIME voters and poll workers who may have come in contact with positive cases of coronavirus at their precincts are being notified.

“He was loving and caring, a family man,” his son Malcolm Burke told Chicago Patch of the hardworking and health-conscious ex-Marine and father of six. “Everybody felt his presence in the room, because he always brought positive energy.”

“He never complained about anything. He kept a smile on his face,” Burke’s friend Mickey Powell told WGN9. “You never saw Revall frown, never.”

Burke had worked as a city employee for 15 years, most recently as a parking enforcement aide, the Chicago Sun Times reports.

He had also been a precinct captain in Chicago’s 17th ward’s Democratic organization for years, “serving our residents and working the election polls,” David Moore, the 17th ward alderman, wrote on Facebook on April 6.

“Stay safe and stay home,” Moore also wrote. “Do it in remembrance of this good brother.” —Madeleine Carlisle

Floyd Cardoz

When Floyd Cardoz opened Tabla in Manhattan’s Flatiron district in 1998, it was a rarity — a modern Indian restaurant with the creative precision of fine dining yet none of the pretense of a staid tasting restaurant. A place like Tabla asked diners to forget what they thought they knew about Indian cuisine — standard curries, doughy naans — and surrender to new interpretations. A spirit of celebration and warmth was pervasive; Cardoz was both fearless about expectations and passionate about his heritage, combining traditional Indian cooking with American, Italian and French twists and techniques.

The restaurant is now part of his legacy. He died on March 24 due to complications from COVID-19 after returning to New York from a trip abroad in early March. He was 59.

At Tabla, a broad, sweeping wooden staircase welcomed diners to a space that was raucous with noise and fragrant with dishes like his take on a clam pizza, or halibut with watermelon curry. (The main floor even hosted a casual “Bread Bar.”) That was Cardoz’s sweet spot: surprising customers and fellow culinary pioneers like critic Ruth Reichl, business partner Danny Meyer and restaurateur David Chang with dishes that challenged perceptions of what Indian cooking could be.

“He was a super-taster, big-hearted, stubborn as the day is long, and the most loyal friend, husband, and dad you could imagine. My heart is just broken,” Meyer said after his death.

Cardoz, born in 1960 in Mumbai, India, trained partially in Switzerland before landing in the U.S. in 1988. After Tabla, he worked at two more restaurants in New York before launching the cozy, hip downtown spot Paowalla (later reimagined and renamed Bombay Bread Bar) and two destinations in Mumbai. At Paowalla, colorful murals decorated the interior’s brick walls, and dishes like bacon-stuffed naan, masala-spiced popcorn or burrata in daal were meant to be shared, epitomizing his style of open-armed hospitality. (His New York locations are now closed.)

He became a food celebrity after winning Top Chef Masters in 2011, where his Indonesian-style short ribs won the day, and also wrote a popular cookbook in 2016, Flavorwalla, filled with spiced-up riffs on family-friendly classics like chicken soup. His latest venture, the imaginative Bombay Sweet Shop, launched this spring. He leaves behind his wife, two sons, five siblings and a trailblazing culinary legacy. —Raisa Bruner

Anthony Causi

There’s a common misconception about sports journalists: that they’re mostly a collection of repressed misanthropes, the guys (yes, mostly guys) who could never make varsity, but who somehow found a way to make an easy living going to ball games. And while this stereotype might be true in rare cases, for the most part, the traveling pack of sports journalists who type the words and shoot the pictures at arenas and stadiums across the country are passionate professionals who work odd, long nighttime and weekend hours far away from their families. The best of them would never complain about their fates—it’s still a hell of a way to make a living—but the job involves its fair share of inglorious gruntwork.

And in those moments after the games, before they have to head back to another faceless hotel room to rest up for the next event, sports journalists often only have each other to lean on. The pack forms a family. They’re good, funny people. They’re guys—and, more commonly these days, women—with whom you’d love to share a late-night beer.

So the April 12 death of New York Post sports photographer Anthony Causi, at age 48 after battling Covid-19, was a particular gut punch to that Big Apple family, which is competitive in the photo pits and press boxes, but particularly tight off the field. Causi was a favorite son. He was the person who, before or after a game, would drop his 50 pounds of photography equipment and insist on snapping a group shot of his colleagues and their families, if they happened to be at the field. “He was always looking to make people happy,” says Post sports columnist Mike Vaccaro, who had the unenviable task of eulogizing his friend in print after his death (Causi carried the Post’s back page). “I know it sounds too good to be true. But it really was.”

Causi, who leaves behind his wife and two children, won the respect of his colleagues and the athletes he covered because he combined kindness with sheer talent. His work speaks for itself: The shot of Derek Jeter touching the “I want to thank the Good Lord for making me a Yankee” sign, Serena Williams at a US Open evening appointment, Megan Rapinoe flashing hardware at a ticker-tape parade, Jeter’s comically unenthusiastic response to Alex Rodriguez joining the Yanks in 2004. Tributes to Causi came pouring in, from Jeter and A-Rod and Conor McGregor, and the New York pro sports teams.

“Great sports photographers are like great point guards,” says Vaccaro. “They have to anticipate what’s going to happen two or three plays ahead.” Vaccaro points to his favorite Causi picture: of Eli Manning hugging his daughters at MetLife Stadium in December, after he played his final game as a New York Giant. “You can see all the other photographers in the background,” says Vaccaro, “not getting the picture Anthony managed to get.”

Among his colleagues, one moment stands out: at spring training in 2016, New York Mets outfielder Yoenis Cespedes took to arriving at the Florida facility in a variety of tricked-out cars. A Polaris Slinghot one morning, a Black Lamborghini the next. The photogs took to staking out the Mets parking lot each day, waiting to snap a shot of the next vehicle. “Only Anthony had the freaking balls to ask Cespedes for a ride,” says Christian Perez, a cameraman for the SNY cable network. Cespedes said yes. So he and Causi went streaking out of the parking lot at about 60 miles per hour. Causi got the shot. He always did. —Sean Gregory

Rabbi Romi Cohn

He was condemned to die at age 13, but his life was spared.

Rabbi “Romi” Cohn explained this as he performed an opening prayer for the U.S. House of Representatives in January. It was the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, and Cohn, a man credited with saving the lives of 56 Jewish families, was there, in part, to remind everyone of the Holocaust that many others didn’t survive — including his own mother and four siblings.

The man known more formally as Avraham Hakohen Cohn died on March 24 after being hospitalized with the coronavirus in his adopted New York City home. He was 91.

Born in 1929 in what is now Slovakia, Cohn was just a teenager when his family slipped him across the border into Hungary as those around him were being forced into concentration camps. Returning home after Hungary started mass deportation, he successfully worked to help Jewish refugees evade the Nazis, supplying them with housing and false papers, according to the Jewish Partisan Educational Foundation. After the war, he moved to the United States and became a successful real estate developer on Staten Island. Cohn was also a passionate mohel, a figure who performs ritual circumcisions; he performed some 35,000 and did so for free. He also trained more than 100 other mohels, on the condition that they also refuse payment.

“Rabbi Cohn lived an incredible life of service,” his congressman, Rep. Max Rose, tweeted upon the news of his death. “His legacy reminds [us] to never accept bigotry,” Rose previously tweeted less than two months earlier, to commemorate his constituent’s prayer at the U.S. Capitol.

That day in January, Cohn was also there to impart a blessing on America’s leaders and lawmakers, people who would soon be struggling to save American lives amid the pandemic that took his own. “May the Lord deal kindly and graciously with you,” the rabbi told them. “May the Lord bestow his favor upon you and grant you peace.” —Katy Steinmetz

John Horton Conway

For most people, there may be no greater oxymoron than “recreational mathematics.” But most people aren’t John Horton Conway, the John von Neumann Professor in Applied and Computational Mathematics at Princeton University, who died from complications relating to COVID-19 on April 11 at age 82.

Conway was best known for inventing the “cellular automaton” Game of Life, which is a two-dimensional grid in which each square interacts with adjacent squares according to certain rules until complexity results. Sounds dry—as long as you overlook the fact that its system-building dynamics explain, well, everything in the world, including life itself.

The mere names of Conway’s books and fields of study capture the playfulness in his genius. He was the co-author of On Quaternions and Octonions and The Sensual (Quadratic) Form. He studied knot theory, tangle theory, surreal numbers and lattices in higher dimensions. As Peter Doyle, professor of mathematics at Dartmouth University and a friend of Conway’s, said in a Princeton news release, “People invariably describe Conway as the inventor of The Game of Life. That’s like describing Bob Dylan as the author of ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’.”

Conway might actually be more notably remembered for co-developing the Free Will Theorem of quantum mechanics in 2004, positing nothing short of the idea that if humans have the freedom to choose which experiments they will run with elementary particles, then the elementary particles have similar free will, able to choose their rate and direction of spin. Doubt that? OK, prove he was wrong.

Then, too, there was Conway’s love of magic tricks, colorful models to illustrate mathematical concepts and the cards, dice and even Slinkys he would sometimes carry with him both for play and for proving principles. “Recreational mathematics” fairly lived within Conway—and it died a small death with his too-soon passing. —Jeffrey Kluger

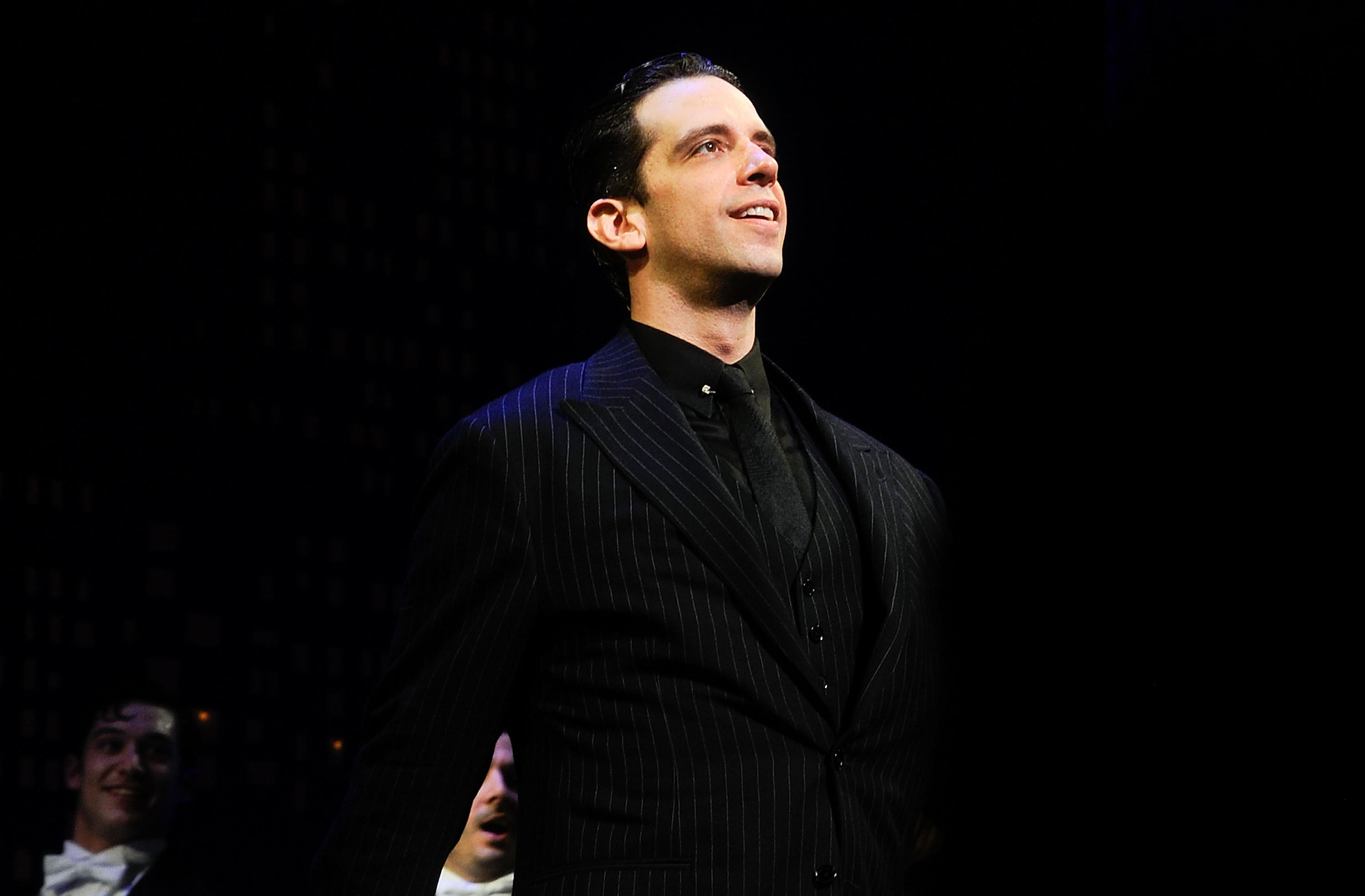

Nick Cordero

Before COVID-19, actor Nick Cordero was in the prime of his life. His wife had recently given birth to their first child, and the young family had moved west after Cordero accepted a role in a play in Los Angeles.

The pandemic changed all that. Cordero, who according to his wife had no preexisting health conditions, contracted the disease in March. He spent the rest of his life in the hospital, facing secondary lung infections, mini-strokes and an amputation—and, as his wife Amanda Kloots shared his daily progress on social media, became one recognizable face of a global crisis.

On July 5, approximately 95 days after he fell ill, Cordero died. He was 41.

Friends remembered Cordero, who was nominated for a Tony Award in 2014 for his portrayal of a tap dancing gangster in Bullets over Broadway, as a vivacious performer, and family recalled a devoted father and husband. “He was everyone’s friend, loved to listen, help and especially talk,” said Kloots.

But as states press forward with reopening, close friend Zach Braff also had a message for the public. “Don’t believe,” the actor wrote on Twitter, “that Covid only claims the elderly and infirm.” —Billy Perrigo

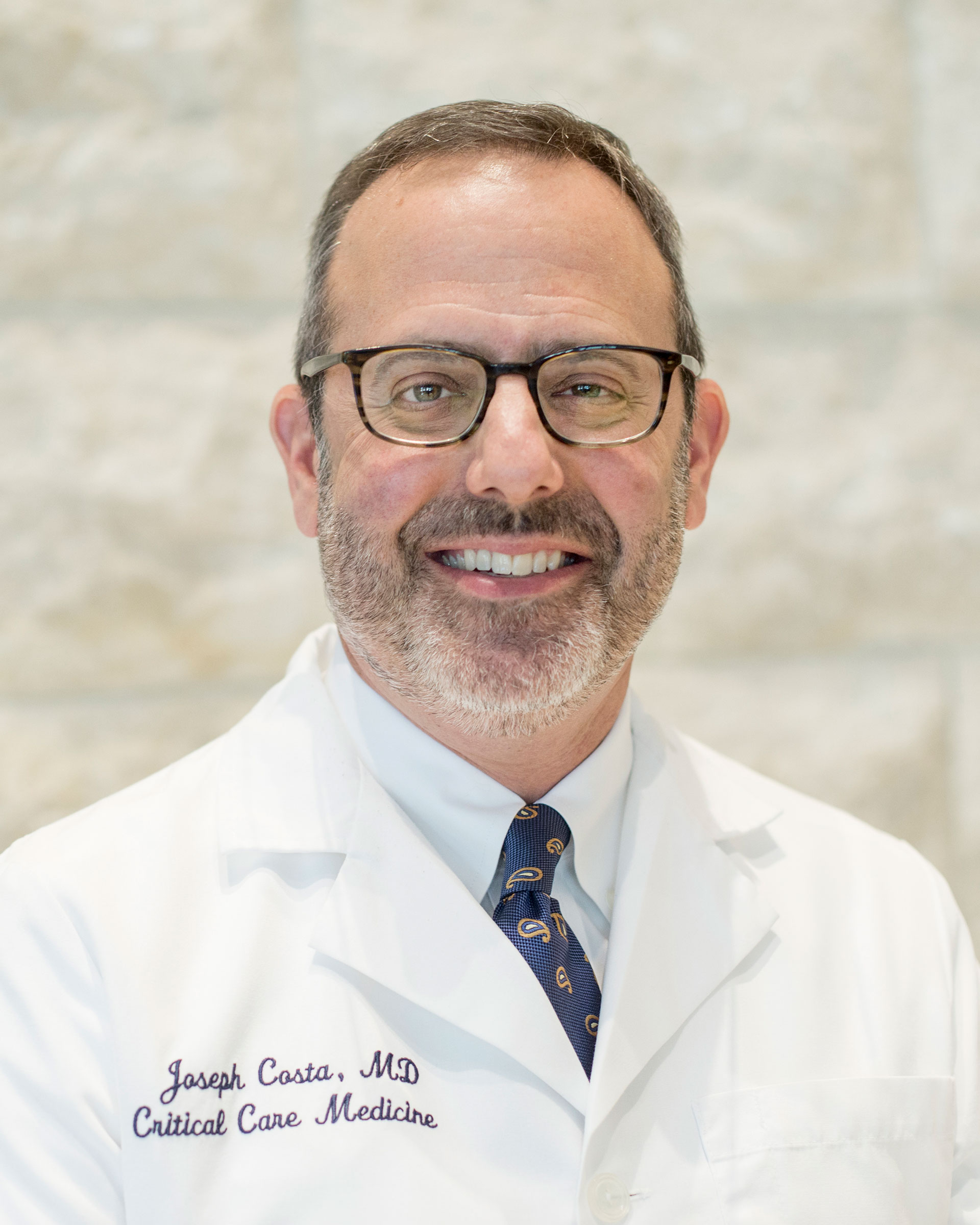

Dr. Joseph Costa

Wrapped in the arms of his husband and encircled by about 20 hospital staff members wearing personal protective equipment, Dr. Joseph Costa, 56, was surrounded by his “family” when he took his final breaths in the very ICU he supervised.

“Those who cared for Joe were his best friends,” David Hart, Costa’s husband of 28 years, told the Baltimore Sun.

Costa, the Division Chief of Critical Care at Mercy Medical Center in Baltimore, worked more than two decades at the hospital, specializing in critical and pulmonary care. But more than that, he was an “older brother” to the nurses and staff who worked closely with him, hospital leaders said in a joint statement.

According to Hart, Costa “lived through his brain,” and was a voracious reader with “stacks and stacks” of books at home. Fluent in both German and Italian, he spent much of the last three years engrossed in Italian literature. Costa was also a pianist, and had recently learned to play the mandolin.

But more than anything, Costa loved being a doctor. Even Hart admitted his husband was a bit of a workaholic, always putting his patients and colleagues first until the very end. The dedicated physician felt it was his duty to work alongside his staff to treat the hospital’s sickest patients, voluntarily working on holidays or grueling overnight shifts—especially amid the pandemic.

Despite suffering from a rare underlying autoimmune disorder, Costa “selflessly” continued to work on the front lines battling the disease. Hart told the Sun that his husband was the bravest man he ever knew.

In a tribute posted to Mercy Medical’s Facebook page, former patients and colleagues flooded the comments with memories and condolences. “I really respected him not only as a physician but as a genuinely kind and caring person,” wrote one former colleague. “He will be greatly missed.” —Paulina Cachero

Julie Davis

The day she heard about the Columbine mass shooting in 1999, Julie Davis decided to become a teacher. “She started saying, ‘Maybe if I could impact a child’s life in a positive way, we would have less tragedies in schools,’” her daughter, Leanna Richardson, recalls to TIME. Although she already had accounting and business degrees, Davis went on to get a bachelor’s in education and teach for more than sixteen years.

Davis had been teaching third grade in person at Norwood Elementary School in North Carolina—one of her favorite activities in the world—until she got a headache on Sept. 24. She swiftly quarantined at home and a test revealed she had contracted COVID-19. Only ten days later, on Oct. 4, she passed away from complications related to the virus. She was 49. In addition to her daughter, she is survived by her grandson, husband, son, sister, two brothers and parents.

Davis was a funny, bubbly and fiercely selfless person who “never did anything halfway,” Richardson shares. “She loved with her entire heart…she would go out of her way for anyone.”

“Students absolutely loved being taught by Mrs. Davis,” Vicki Calvert, interim superintendent of Stanly County Schools, said in a statement. “Her personality was infectious and she brought joy into the lives of the students, staff, and community.”

And Davis adored her students right back. “She loved nurturing them and teaching them and watching them grow,” Richardson says, adding that her mom was always planning a lesson, grading papers or talking to students. “She never stopped.” —Madeleine Carlisle

AshLee DeMarinis

AshLee DeMarinis loved to teach—and felt a special bond with the seventh- and eighth-grade special education students who needed her help the most.

“She loved the connection with the kids,” her sister, Jennifer Heissenbuttel, tells TIME.

DeMarinis was a little nervous about returning to John Evans Middle School in Potosi, Missouri, this fall to start her eleventh year teaching, Heissenbuttel says, but she planned on still teaching despite the potential risks associated with the pandemic.

But in late August, before the students had even returned, DeMarinis was hospitalized for complications related to COVID-19. She died three weeks later at age 34.

“Her commitment and passion for her students and community to succeed should be an inspiration to all of us,” Potosi Superintendent Alex McCaul wrote in a letter announcing her death. “Ms. DeMarinis touched many lives as an educator and will be missed dearly by our community.”

Heissenbuttel says her sister helped her students and the community in ways large and small. If a child in her class couldn’t afford to have a birthday party, she’d throw it for them. She was active in Potosi’s St. James Catholic Church and she would also buy groceries for low-income families around town.

While she grew up in Queens, N.Y., DeMarinis moved to the Midwest to attend school. She also loved to travel.

“She always liked to go to new places. She loved taking road trips, doing new things,” says Heissenbuttel. “She was adventurous.” —Madeleine Carlisle

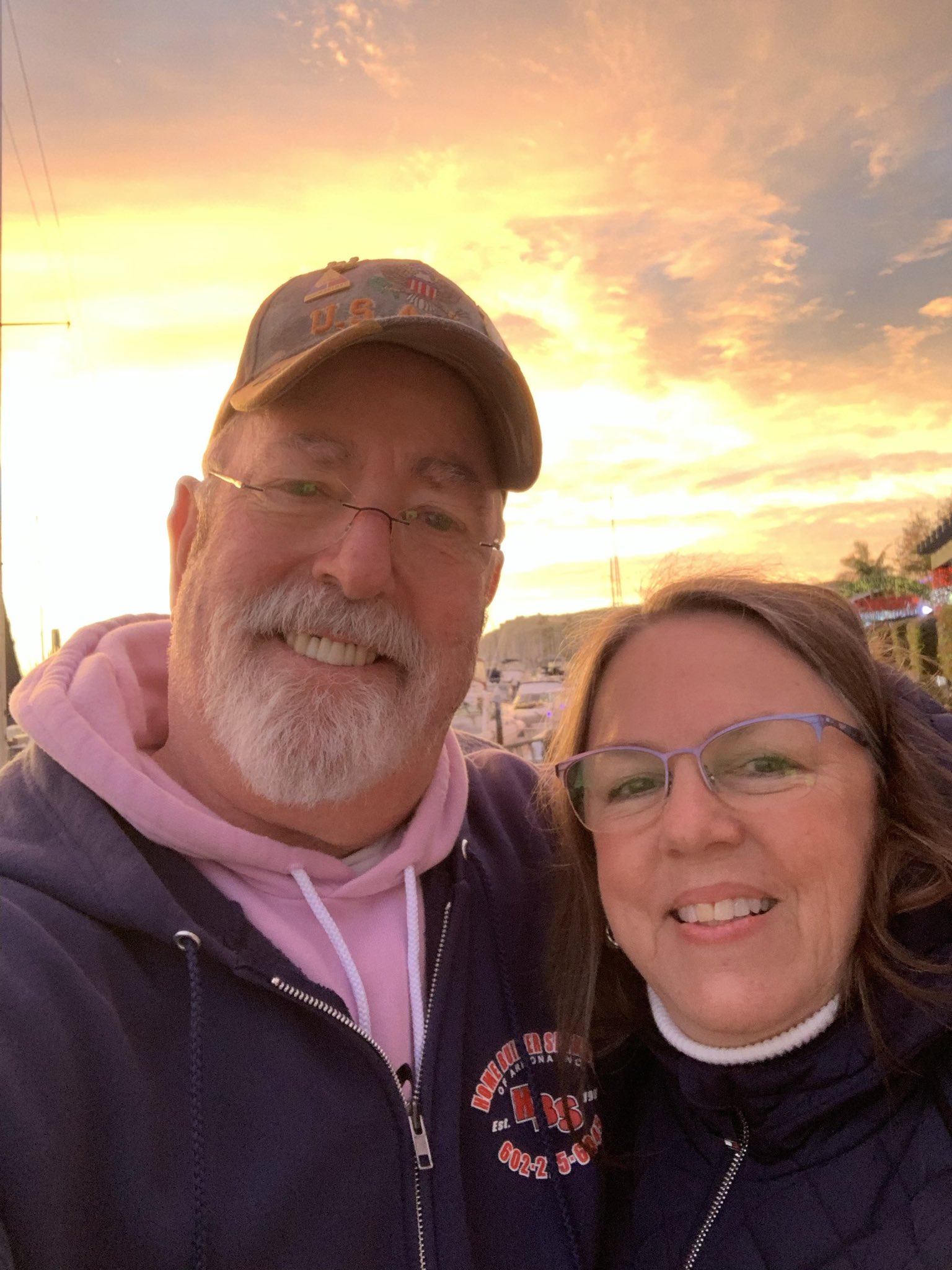

Lonnie Dench

As one half of the open-hearted couple who famously welcomed a random teen into their Arizona home for Thanksgiving, Lonnie Dench was renowned for helping give rise to one of the most heartwarming holiday traditions known to the internet.

Now, the annual custom is how he’ll be remembered by many it inspired.

On April 5, the husband of the grandma who went viral for accidentally inviting the teen to celebrate the holiday with her family in 2016 died from complications from the coronavirus.

Jamal Hinton, the now 20-year-old who spent every Thanksgiving afterward with Lonnie and Wanda Dench since Wanda mistakenly sent him a text meant for her grandson four years ago, announced on Twitter on April 1 that Lonnie had passed away.

“As some of you may have already found out tonight Lonnie did not make it… he passed away Sunday morning,” Hinton wrote. “But Wanda told me all the love and support he was receiving put a huge smile on his face so I thank every single one of you guys for that!”

People looked forward to their meaningful connection each year. “We just sit at the table for a couple of hours and talk the whole time and tell stories and see how we’ve been,” Hinton told TIME in November of the group’s shining hospitality example.

News of Lonnie’s passing comes a week after Hinton tweeted that both Lonnie and Wanda had COVID-19 and that Lonnie was in the hospital with pneumonia in addition to coronavirus. Wanda is under a two-week quarantine, Hinton and his girlfriend, Mikaela Grubbs, said in a YouTube video.

Hinton also recently shared a brief video of Lonnie with Wanda, which demonstrated his fun and generous spirit. “We miss you Lonnie,” Hinton wrote.

Wanda also confirmed Lonnie’s death to local news site AZFamily, describing him as the first to welcome people on Thanksgiving and the last to say goodbye. “He had the truest heart of love, like no other,” she said in a statement to the outlet. “He did so many acts of kindness that no one ever heard about. He was my hero. And I’m a better person because of him.” —Megan McCluskey

Marguerite Derrida

Through her painstaking translations, she brought examinations of Russian folk tales and Austrian psychoanalysis to France.

Now, her work is part of her legacy. Marguerite Derrida, a prominent French psychoanalyst and translator, reportedly died of the coronavirus on March 21 in a Parisian retirement home. She was 87.

She translated the books of Melanie Klein, an Austrian-British psychoanalyst studying children, as well as Russian authors like Vladimir Propp, a scholar focused on the structure of Russian folk tales—bringing their works to a wider audience. She also worked as a clinician after attending the Psychoanalytic Society of Paris.

Ms. Derrida was also known for her marriage to Jacques Derrida, deemed by some as the world’s most prominent philosopher. On Twitter, Philosophy Matters praised her as a “brilliant and dynamic woman” in her own right, who was also “very kind.” The Institute for Advanced Studies in Psychoanalysis also lamented that with her death, “a whole world is leaving.”

From the beginning of her life, Ms. Derrida was surrounded by intellectuals. Born in Prague, her father, Gustave Aucouturier, served as editor-in-chief of Agence France-Presse, an international news agency. Her brother, Michel Aucouturier, eventually became a renowned French expert in Slavic studies.

It was Ms. Derrida’s brother who introduced her to Jacques Derrida in 1953. Four years later, they married in a non-religious ceremony in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Mr. Derrida was studying at Harvard University. In the late 1960s, the couple moved to a modest home in the Parisian suburb Ris-Orangis where Ms. Derrida began studying anthropology with André Leroi-Gourhan.

In the decades that followed, Mr. Derrida’s philosophical work gained international attention. He became known for deconstruction theory—the notion that language and ideas carry contradictions and thus, should not be embraced wholeheartedly. He died in 2004.

The couple is survived by their two sons, Pierre Alferi and Jean Derrida, who have become notable thinkers in France, carrying forward their parents’ intellectual legacy. —Melissa Godin

Dr. Jim Dornan

Dr. Jim Dornan was likely best known in the United States as the father of Fifty Shades of Grey actor Jamie Dornan, but to the people of Northern Ireland he was a “true visionary” and leading ob/gyn who dedicated his life to helping many people and worthy causes. The elder Dornan died on March 15 in the United Arab Emirates after contracting COVID-19, according to multiple reports. He was 73 and had previously been diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 2005.

“Jim was a wonderful man,” MP Ian Paisley Jr. told the BBC after Dornan’s death. “His ambition, expressed often to me, was to see Northern Ireland and its people flourish and be the best. No obstacle was ever insurmountable for him and he was a great source of encouragement.”

Dornan was also President of NIPANC, a pancreatic cancer charity in Northern Ireland, which confirmed his death and coronavirus diagnosis on social media. His first wife, Lorna, died of pancreatic cancer 1998 when Jamie Dornan was 16. He also leaves behind his second wife, Dr. Samina Dornan, and two daughters, Liesa and Jessica.

The veteran doctor delivered many babies over the years, published numerous research papers on maternal and fetal health issues, and chaired the Health and Life Sciences department at the University of Ulster. He was also president and a founding member of the TinyLife, a charity that aids premature and vulnerable babies in Northern Ireland, which noted that his “inspirational and groundbreaking work has impacted the lives of babies worldwide.”

“It is with deep shock and profound sadness that we hear of the passing of our much loved and highly esteemed colleague,” a spokesman for the Belfast Trust told Belfast Live. Dornan reportedly worked with the Trust as a consulting ob/gyn for more than 25 years. “His contribution to Obstetrics and Gynaecology both nationally and internationally was immense. Jim’s encouragement, zest for life and a real humanness endeared him to us all and to the many, many women he cared for over the years and we will miss him.” —Kathy Ehrich Dowd

Roml Ellis

Since the start of the COVID-19 outbreak, essential workers who have always worked behind the scenes to keep American society moving have shifted into the spotlight as they’ve been called upon to continue working during the pandemic. One of these workers was Roml Ellis of Jeffersonville, Indiana, who worked as a UPS employee for 36 years.

At the time of his death, he was working as a supervisor at Worldport, UPS’ worldwide air hub based at Louisville Muhammad Ali International Airport, according to WDRB, a Louisville-based news source. Although he had no known preexisting health issues, he died on April 4 after testing positive for COVID-19, Clark County Health Department in Indiana confirmed to WHAS. He was 55. UPS declined to comment to TIME on his death.

Growing up in Louisville, Ellis always dedicated himself to anything he set himself to, whether it be his studies or football, Tim Murphy, Ellis’s friend since elementary school, told TIME. A teammate of Ellis’ through elementary school and high school, Murphy said that while Ellis was reserved, he had a sly sense of humor and was always someone you could count on.

“You could trust in what he’d say. If he said he would do it, he would do it,” Murphy said.

Ellis’ dedication later carried him to a football scholarship at Georgetown College, and he later graduated from the University of Louisville, according to his obituary.

Later in life, Ellis’ priority shifted to his three sons, according to Murphy, and his dependability served him well as a father. “There was always a sense of calm around him, because there was never any doubt that he would keep up his end of the deal.” —Tara Law

Helen Etuk

Helen Etuk greeted nearly everyone she met with a smile. “She was so happy,” her older brother Jeff Ayisire tells TIME. “We would just call her a gentle soul.”

A senior at the University of North Texas (UNT), Etuk was dedicated to her studies, her family and her Christian faith. On track to graduate in 2021, she planned on continuing to medical school to become a pediatrician. “That was her drive, to just go ahead and help kids,” Ayisire says. “And of course her biggest goal was to get to the point financially where she [could] help my mom to never work again.”

But Etuk never had the chance to reach those goals. She died on Jan. 12 from complications related to COVID-19. She was 20.

“She was somebody who’s just about love and forgiveness and peace,” says Ayisire. “Someone that was strong of faith. Even to her last breath, she was always telling us to be strong, and just continue to love and believe in God.”

In the fall, Etuk returned to attending in-person classes after UNT reopened, promising her family she’d be extra careful to take social distancing measures since she suffered from lupus, a disease of the immune system. But she developed a bad cough in October, Ayisire says, and returned home to Arlington, Texas, to be safe. Her condition soon worsened, and she lost her sense of taste and smell. She then became unable to walk down stairs without being carried. Etuk was hospitalized in early November, and never returned home.

Etuk is survived by her mother, five brothers, and three sisters. Her family is raising money for a scholarship to UNT in her name, to honor her love of learning. Her mother also hopes to create a nonprofit to help support people suffering from lupus, Ayisire says. “Those are some things we’re trying to do to have her legacy live on.” —Madeleine Carlisle

Adeline Fagan

Even when life was a challenge, Adeline Fagan chose to focus on the good things to happen each day.

“After a great day at work, or even a terrible day, I could always count on her to come home and be like, ‘Maureen, do you want to watch Moana?’” Maureen Fagan, one of Adeline’s three sisters, tells TIME. Although Adeline was endearingly uncoordinated, they would sing and dance together to Disney songs to blow off steam, Maureen says.

But their ritual ended for good on Sept. 19, when Adeline died after a long battle with COVID-19. She was 28 years old, and two years into her residency as an OB/GYN in Houston.

Although Adeline’s work mostly involved delivering babies, she had begun to treat COVID-19 patients in the ER. On July 8, Adeline came home from work feeling sick. By Aug. 3, she was placed on a ventilator. On the morning she died, her parents were there to hold her.

The Fagan family is sharing Adeline’s story with the hope that the public will more fully understand the seriousness of COVID-19, and that even young people are susceptible to the virus.

“This most likely could have been prevented,” Maureen says. “A 28-year-old, who really only had the underlying condition of asthma, is dead.”

Maureen plans to follow in Adeline’s footsteps and become a doctor as well. “I want to try to fill those shoes and continue on the legacy that she’s left behind,” Maureen says.

Adeline’s father, Brant Fagan, also encourages the public to be more like Adeline.

If you can do one thing, be an ‘Adeline’ in the world,” he wrote in a public message on the day of Adeline’s passing. “Be passionate about helping others less fortunate, have a smile on your face, a laugh in your heart, and a Disney tune on your lips.” —Jasmine Aguilera

13 Felician Sisters From One Michigan Convent

Thirteen religious sisters from the same convent have died from the coronavirus, with twelve passing in the span of a month.

The women, aged 69 to 99, were all members of a Felician Sisters convent in Livonia, Michigan.

On Good Friday, the virus took the life of Sister Mary Luiza Wawrzyniak, 99. By the end of April, eleven other sisters had passed. A thirteenth sister, despite an initial recovery, passed away in June.

“The sisters in Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mother convent in Livonia—as well as all of us in the province—are still very much dealing with the loss of so many sisters,” Suzanne Wilcox English, Executive Director of Mission Advancement for the Felician Sisters of North America, tells TIME.

The sisters, all of whom were longtime members of the convent, lived, prayed and worked together. Prior to their retirements, the women had worked as school teachers, college professors and principals; librarians, nurses and organists.

Sister Wawrzyniak had “served as the ‘sunshine person’ for the local ministry sending feast day and birthday cards to the Sisters in the infirmary,” an obituary reads; Sister Victoria Marie Indyk, 69, led nursing students on regular trips to the Felician Sisters’ mission in Haiti. Sister Rose Mary Wolak, 86, spent eight years working as a secretary in the Vatican’s Secretariat of State; Sister Thomas Marie Wadowski, 73, once led a second-grade class to win a national prize in a Campbell’s Soup commercial competition.

For many sisters, who normally pray alongside those who are dying, having to socially distance during a time of grief was difficult. “Normally, we will share stories about the sister we have lost during the vigil, the night before the funeral, but we have been unable to do so,” says English, who adds that “their collective impact on the community has been, and continues to be, very deep.” —Mélissa Godin

Alan Finder

Alan Finder wore many hats during his three decades at the New York Times. As both a reporter and editor, he covered New York City government, international news, sports, higher education, labor, transportation and much more.

But no matter the subject, Finder approached his stories with the same even-keeled work ethic and attention to detail. He challenged power structures and gave voice to the disenfranchised; he was beloved by colleagues and served as an essential mentor to several generations of budding journalists. He died at 72 on March 24 after battling coronavirus for several weeks.

On Twitter, Times editor and reporter Richard Perez-Pena called him “the greatest colleague I’ve ever had and one of the best people I’ve known” and also noted that “Alan was a font of sanity, decency, wisdom, humor and calm in a crazy, often harsh business.”

Finder was born in 1948 in Brooklyn and started his career as a local cub reporter for the Bergen Record in Hackensack, N.J. After a four-year stint at Newsday he joined the Times in 1983, where he distinguished himself for his diligent approach to covering highly technical and corruption-plagued realms like housing, labor and transportation.

When Joan Nassivera arrived at the newspaper in 1988 as an editor, the first story she edited was one of Finder’s. “He understood who pulled the wheels of power and how these people intersected—and could explain it all to the average reader and make it interesting,” she said. “He treated editors as equals or better, even though he didn’t really need any help.”

In 1994, his reporting deflated New York City’s claim that it was giving more city contracts to women- and minority-owned companies. The next year, he uncovered the grotesque practices of New York City’s sweatshops, writing about 12-hour-days and fire doors sealed shut by large padlocks.

Over the next decade-plus, Finder would prove his flexibility, serving as a sports editor, then an education reporter, then an editor on the international desk. He took many journalists under his wing, offering them invaluable advice or just an open ear.

“He was a guy who people looked to for guidance and for help,” said Patrick McGeehan, a New York Times reporter who called Finder a friend and colleague for more than a decade. “It was not at all uncommon to see him huddled with someone, talking very quietly.”

When Finder died he was still working editing shifts at the Times, but was spending more time with his wife Elaine, daughter Lauren, and son Jacob. “He didn’t take himself seriously, and he took his job seriously enough to be one of my two favorite editors ever,” Nassivera said. “But what he did take seriously was his family.” —Andrew R. Chow

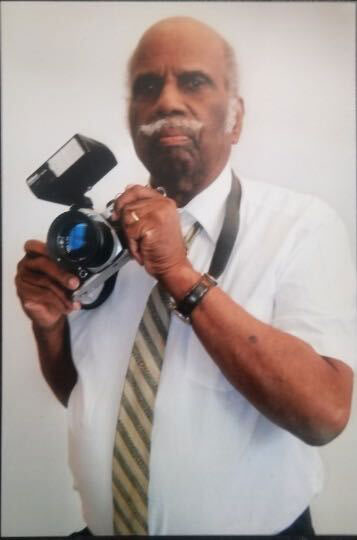

Theodore Gaffney

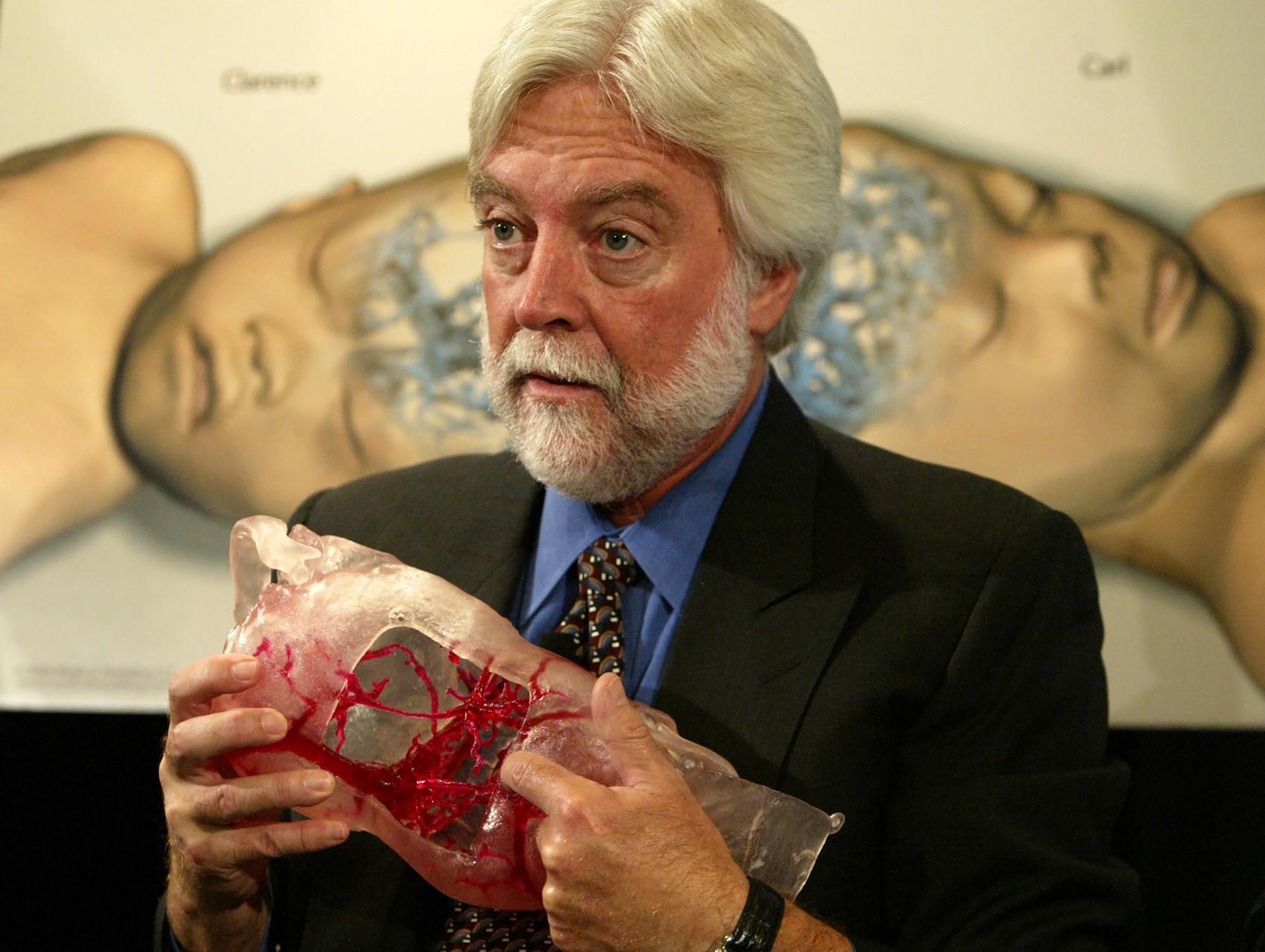

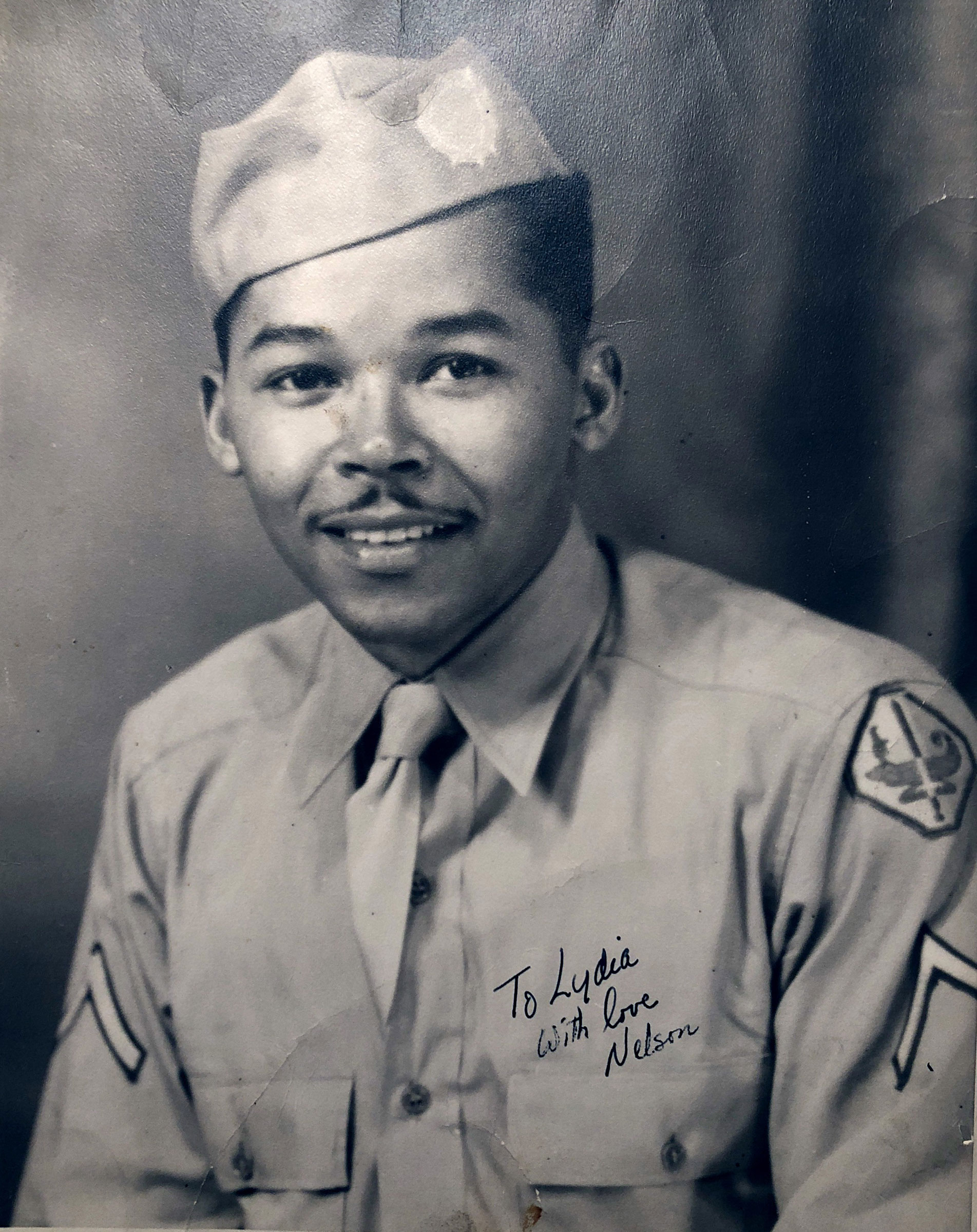

When Jet magazine asked the photographer Theodore Gaffney to travel with the Freedom Riders in 1961 to document their journey to Birmingham, he agreed without thinking twice. “I didn’t think anybody was going to be violent because there was nothing violent about me,” he said in the 2011 “Freedom Riders” Interview Collection.

Gaffney ended up with a front-row seat to one of the most significant events of 20th-century American history. The Freedom Riders, who traveled the American South to challenge the segregation of buses and terminals, revealed American injustice to the world, charted a course of nonviolent action that would lead to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and galvanized a new generation of civil rights leaders. Along the way, they were met by vicious mobs and eventually federal intervention. And Gaffney was there to capture it all. On Easter Sunday, the longtime photographer died at age 92 from the coronavirus.

“He was interested in documenting the struggle of people of African descent here in the U.S.,” his wife, Maria Santos-Gaffney, tells TIME. “He would say, ‘If you don’t believe you can change things, you won’t know until you try.’”

Theodore Gaffney was born Nov. 22, 1927 in Washington, D.C. He was the descendant of slaves who worked on a plantation near Gaffney, S.C., his cousin Patricia Johnson told the Washington Post.

When Gaffney came of age, he enlisted in the Army and entered active duty just after World War II. After his service ended, he took classes at Catholic and Howard Universities and developed an interest in photography.

As a photographer, he spent much of his time photographing politicians and activists on Capitol Hill. In 1956, he found himself the subject of news when pro-segregation Sen. Olin Johnston ordered a Senate guard to seize his film after Gaffney took a picture of Johnston and NAACP representative Clarence Mitchell.

Five years later, when Gaffney was 33, Jet asked him to join the Freedom Riders. The rides would soon turn violent as mobs targeted the buses. Gaffney says his position made him especially vulnerable, since their attackers did not want their violence documented. At one point, white supremacists boarded the bus and began beating activists. Gaffney snapped two pictures and then slipped his camera back into his pocket.

“I was wondering if I was crazy,” he said in the 2011 interview. “I don’t know how they train you to be nonviolent when you’re getting your head beaten. I was afraid I might not come back.”

Gaffney made it out safely and resumed work on Capitol Hill. He was retired and living in Brazil when he met his wife in 1986.

“While in Brazil, he would be out and about all day long, going to the historic sites, talking to young people, trying to encourage them to get educated,” Santos-Gaffney says. The pair was married two years later; they moved to the U.S. and had two children, Theodore and Walter Santos-Gaffney.

Even in his last weeks, Santos-Gaffney says her husband retained his inquisitive spirit. “He was reading everything he could get his hands on,” she says. “His mind was very active.”—Andrew R. Chow

William Garrison

After 44 years behind bars as a juvenile lifer, William Garrison was set to be released from the Macomb Correctional Facility in Michigan on May 6.

But just three weeks short of that date, on April 13, he died of complications from the coronavirus. He was 60 and one of 39 inmates to die from COVID-19 in Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) facilities as of April 28.

Garrison’s sister Yolanda Peterson supported her brother during his decades behind bars, and had been preparing a room for him in her home for when he was released; it was approved by a parole officer just one day before his death. “My brother shouldn’t have died in there like that,” Peterson told the Detroit Free Press. “He was looking forward to getting out.”

At 16, Garrison was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison without parole in 1976. He was recently resentenced, following a 2018 Supreme Court ruling that banned life-without-parole sentences for minors, and was offered parole in February. However, he turned it down because he felt the court had done him an injustice with his original sentence, according to MDOC spokesperson Chris Gautz.

Garrison had accrued “more than 7,000 days of good time credit” while incarcerated, “and thought he should be allowed to be freed without parole,” Gautz tells TIME. “This was just an unfortunate case all the way around.”

Garrison was later identified among prisoners “vulnerable” to COVID-19 as it began spreading in jails and prisons across the U.S., and was included in an MDOC list of parole-eligible inmates who could have been released early. Although he had consented to be paroled on those grounds, Garrison died while waiting to hear if the county prosecutor’s office would appeal his release.

Other Macomb inmates have since said Garrison’s cellmate had been sick prior to his death, Yolanda Peterson claims. MDOC spokesperson Chris Gautz says that Garrison had not reported any symptoms or illness (he was tested for the coronavirus only after his death) and that his cellmate has since tested negative.

Becky Hahn, Garrison’s attorney, told the Free Press he was passionate about advocating for incarcerated people and helping them with legal matters: “I really do think that if he was here, he would want his death to shed light on the dire situation that those others are facing in MDOC.” —Josiah Bates

Vickey Gibbs

Even as Rev. Vickey Gibbs was ill in a hospital bed, stricken by the coronavirus, the pastor’s cell phone continued to be flooded with messages from her congregants. “There were still so many people calling or sending texts, asking, ‘Can you call me today? Can we pray today?’” Cassandra White, Gibbs’ wife, tells TIME.

Gibbs, an associate pastor at Resurrection Metropolitan Community Church in Houston, was an indispensable church leader, quick to provide members with prayers, homemade food, or her signature warm smile.

“Her not being here is not only a huge loss for me and my family, but it’s a huge loss for many who relied on her,” White says.

After her death, on July 10 at age 57, tributes to Gibbs poured in on a Facebook page dedicated to her memory.

Over the course of nearly 40 years at the congregation, Gibbs became an invaluable pillar of the church, developing diversity and inclusion curriculums and helping to establish a gospel ensemble focusing on African American worship music.

On June 7, as the country erupted into protests over the deaths of Black Americans including Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd, she delivered an impassioned final sermon, decrying the insidious fractures that plague the U.S. Gibbs challenged church members to confront inequality and injustice head on.

“We can begin to create the change that we say we seek,” she said during the sermon. “We must be the bridge to equality by demanding change.”

Gibbs is survived by her wife, two daughters, and her 18-month-old grandson. Ever a meticulous planner, Gibbs left behind a detailed list of things that White should do in the event of her passing. “In one of the lines she wrote, ‘I apologize, I was hoping we would have more time together,” White says. Gibbs also requested to tell “Boo”—her nickname for her grandson—that she loved him every day. —Paulina Cachero

Annie Glenn

Sometimes a life ends on a little whiff of poetry. So it will be for Annie Glenn—widow of astronaut and Senator John Glenn—who died of complications from COVID-19 at age 100 on May 19. When Glenn’s virtual memorial service is held on June 6 it will be presided over by the pastor of the Broad Street Presbyterian Church in Columbus, Ohio: the Reverend Amy Miracle.

In many ways, Glenn’s life was its own sort of century-long miracle. It was miraculous that she met her future husband literally in the playpen, when she was three and he was just 19 months old. (Their parents were part of a local cards club.) It was miraculous that they married 20 years later, in 1943, and remained together for 73 years until Senator Glenn’s death in 2016.

“I have never known a world that didn’t include Annie,” he told me when I spoke with him before his second flight to space, at age 77, in 1998.

And it was miraculous too that Annie Glenn survived and thrived in a national spotlight for decade upon decade while suffering from a stutter so paralyzing that when she was a young woman, she would write down her destination and hand the paper to a bus driver rather than attempt to speak her stop. Glenn eventually overcame the problem after undergoing intensive therapy in the 1970s, and went on to campaign for her husband during his presidential run in 1984. She was honored with the Department of Defense Medal for Outstanding Public Service in 1998, but more important was the annual award named for her by the National Association for Hearing and Speech Action, in 1987.

It is a story often told—and a true one—that before John Glenn went off to war in 1944, he told his then-new wife that he was just going down to the corner store for a pack of gum. He would repeat that little ritual over the years before military missions, test-piloting flights and his two trips to space. Widowed for four long years after a marriage of more than seven decades, Annie has now, at last, joined John at their corner store. —Jeffrey Kluger

Fred the Godson

Fred the Godson’s lyricism often seemed to emanate from a different era of hip-hop. The compact Bronx wordsmith constructed his verses with a keen attention to cadence, puns, punchlines, assonances and homonyms; he was revered by many rappers and producers as one of the sharpest writers in the rap community.

“I always try to bust my brain to think about things nobody would think about, so I can prove to people I belong in this joint,” he said on the radio show The Breakfast Club in 2011.

After a decade-long career, Fred the Godson died on April 23 from complications of the coronavirus. He had been in the hospital for several weeks; on April 6, he posted a picture of himself wearing an oxygen mask on Twitter, writing, “Please keep me in y’all prayers!!!” He was 41, according to his manager David Evans.

Born Frederick Thomas in the South Bronx, Fred the Godson grew up in poverty, with a father who struggled with crack cocaine use. When he was a child, a fire in his apartment forced his family—which included his parents and five siblings—into a two-room shelter.

As a high schooler, Fred the Godson was a firsthand witness to New York’s golden age of hip-hop in the ‘90s, in which the Notorious B.I.G., Nas and Jay-Z all rose to prominence out of low-income neighborhoods. Fred the Godson idolized that slick-talking, verbose trio and rapped casually himself, but was hesitant to pursue it as a career: “I looked at rappers like superheroes,” he said in a 2012 interview. “I have rappers on this pedestal that was so high, I never thought that I could reach it myself.”

But as he progressed as a wordsmith, lacing his rhymes with metaphors and witty homonyms, he quickly realized his skill far outpaced that of many in the field. His first two mixtapes, Armageddon and City of God, became cult favorites in an era when mixtapes were still a dominant part of the hip-hop landscape. In 2011, he landed on the cover of XXL Magazine as part of their annual Freshman Class, alongside Kendrick Lamar, Meek Mill and Mac Miller.

Over the next decade, Fred the Godson would deliver hundreds of voluminous, pugilistic verses on his own mixtapes and other artists’ projects. He collaborated with Diddy, Pusha T, Busta Rhymes, Fat Joe, Meek Mill and many other high-profile artists. He continuously resisted signing with a label: “There’s a lot of rappers I know that are signed and don’t make as much as me,” he said in a 2017 interview.

While he didn’t receive the chart success of his aforementioned colleagues, he became a respected underground veteran. His verses were stuffed with double entendres and wordplay that made listeners rewind their tapes. These included: “No label, the block signed him/ Flow off the noodle, I’m top rhymin’ [top ramen]’”; “These A&Rs are comedians like Jerry/ Cause everything they sign fell [Seinfeld]”; “Professionals built the titanic, but amateurs built the arc/ Yeah I nailed it, the hammer is in the park/ My flow they cut and paste, my grammar is very sharp.” =

He was especially active over the past six months, releasing three tapes: God Level in November, Training Day with SNL alum Jay Pharaoh in January, and Payback in March. But in early April, he was taken to the hospital, where he died several weeks later. His numerous health isses, including kidney failure, high blood pressure and diabetes, put him at higher risk after contracting the coronavirus.

The radio personality Sway Calloway said that Fred the Godson “personifies what a true MC is.” The DJ Clark Kent called him “easily one of the most dangerous MC’s around.” And the rapper Kemba, who is also from the Bronx, said he looked up to Fred the Godson as an aspiring lyricist. “Everyone thought he was the best,” he wrote on Twitter. “I was trying to be as good as he was.” —Andrew R. Chow

Mariah and Adan Gonzalez

For his fifth birthday, little Raiden Gonzalez is wishing for Hot Wheels and dinosaurs. But more than that, he is wishing for his parents, who died less than four months apart of COVID-19 earlier this year.