In 1937, the Carnegie Corporation hired a Swedish man to unravel an American quandary. The foundation had a history of funding initiatives to help the disadvantaged; in the U.S., where enslavement was only 72 years gone, the disadvantaged were disproportionately Black. The issue was often described as, simply, “the Negro Problem.”

But while it was clear that the problem existed, it was also obvious how difficult it was to solve. And so the foundation brought in economist, sociologist and future Nobel Prize winner Gunnar Myrdal to gather information to guide its programs.

Myrdal did much more. Almost seven years later, he produced a two-volume study he dubbed An American Dilemma, exploring, in statistical detail, the evidence of the great American lie—the gap between the nation’s ideals and its racial reality. Myrdal was far from the first to try to illuminate the effects of ongoing institutional racism, the frequent and extreme way it pushed the U.S. away from its core ideals and constitutional promises. And he certainly would not be the last. Alexis de Tocqueville in 1835, W.E.B. Du Bois in 1900 and again in 1935 and the Kerner Commission in 1968, among others, enriched our national understanding of troubles we still face today. But Myrdal and his army of social scientists seemed, for at least a time, to cut through America’s fairytale understanding of itself. The study was one of just a few credited with prompting the Supreme Court to put a legal end to school segregation.

And yet, once again, Myrdal’s subject looms large. The profoundly inadequate question of whether America is a racist country has caused a wave in many elected officials’ deep-as-a-puddle meditations on the nation’s history. Many Americans remain ill-informed about race and near delusional in their description of its reach. The evidence is clear—and was, in a way that all but only the most recalcitrant can deny, made plain again in the extended endurance test that began in March 2020.

Read more: America’s Long Overdue Awakening to Systemic Racism

If the past year has been, as is so often claimed, the one in which the ugly scar of American inequality ripped open so wide that few could deny it, it should also be known as the year when a bold and opportunistic set learned to better talk the talk of needed change. Still, even in a country that prides itself on allowing citizens to speak freely and then act to change public policy accordingly, the renewed attention given to racial injustice has scarcely been matched with parallel action.

The problem is as clear as ever. What America is going to do about it is not.

The same basic information is the backdrop of Myrdal’s work and everything that came before and after. In a country founded on a commitment to equality, white Americans have been the only ones to consistently enjoy the full measure of citizenship. Settlers drove Native Americans from their own lands and then treated them as unwelcome, dangerous guests. Congress barred many others from even entering the country. But it was Black Americans whom the nation enslaved, then so completely marooned that in every major measure of social, economic or physical well-being, millions would—and still do—remain far behind their white compatriots.

When Myrdal’s work was published, Black Americans earned less, were more likely to be unemployed, and led shorter and unhealthier lives. In the North, their housing was crowded and substandard. In the South, many did not have access to anything beyond basic elementary education. Most Black Americans could not vote or borrow the funds to buy property. “Virtually the whole range” of public amenities, from hospitals to libraries, were “much poorer for Negroes than they are for whites,” Myrdal wrote. The majority of Black Americans had little to no assets and were the targets of disproportionate incarceration and exploitative profit-making schemes.

Nearly 80 years later, we find ourselves more than a year into a pandemic, a recession and a reconsidering of the meaning of Black death caused by agents of the state. Last summer’s mass protests have for the most part receded. But increased crime, increased poverty, increased death and increased distress have not. Yet in our litany of collective aches, there is almost no arena in which Black Americans have not suffered more than white Americans.

Black Americans on average earn less with the same (or, in some categories, more) education than white workers, are more likely to be unemployed and are clustered in industries hit hard by the pandemic. Black Americans are more likely to be born premature and to die younger. In fact, life expectancy for a Black boy born in 2020 is a full seven years shorter than a white boy’s. Black women remain more likely to die in or just after childbirth than white women. All Black Americans are more likely to die of cancer than white Americans. The impact of the coronavirus was anything but novel: the death risk for Black Americans is almost two times that of white Americans.

It doesn’t stop there. Black children remain more likely than white ones to attend high-need, low-performing schools, low-quality preschools, and high schools that offer few if any college-prep courses. The Black homeownership rate in the first quarter of 2021 was 29 percentage points lower than that of white Americans. When Black Americans do own homes, those properties are often undervalued by appraisers. That disparity—not saving, spending or even earnings—drives the bulk of the nation’s massive Black-white wealth gap. Black Americans are also more likely to live in “nature”-deprived areas than white Americans and experience more exposure to pollutants. Black incarceration rates continue to outpace those for all other groups, and the effort to restrict Black voter participation, which has been a part of American politics since Reconstruction, has resurged today.

And yet, just as was the case when Myrdal was working, many of those in power have the temerity to express total shock about those vast racial disparities, to confuse the causes of inequality with its effects, and to question what, exactly, is wrong with Black Americans. Or Latino Americans, Asian Americans, Native Americans—take your pick. As distinct as the Black experience is, so many communities throughout the U.S. have their own parallel set of facts.

Read more: How a Road Trip Through America’s Battlegrounds Revealed a Nation Plagued by Misinformation

These problems are not products of the long pandemic. But many were made worse, and perhaps the copious concern about being “woke” to inequality (or deeply opposed to anything like it) has hitched a fast ride on the virus to the cultural forefront. Corporations that only years ago reached massive settlements with the U.S. government for engaging in what federal officials alleged was widespread discrimination have released carefully worded statements declaring that Black lives matter. Promises have been made. They will have to be tracked. In the interim, the Dear Black, Latino, Asian employees, we see you and feel your pain email after a horrible event in the news has become a new genre of corporate communication. The very same impulse is also a feature of a certain set’s social media feeds and the launching point for thousands of online lists of goods created by people of color, to be bought by those who wish to understand themselves as good.

But even among those white Americans who do not live in a state of denial, the call to action has once again grown faint, if it was ever there at all. Few companies have been so public in discussing how employees involved in unfair practices might actually be penalized, or how the obligation to operate with equity in mind will be prioritized above profits. Few organizations or individuals have acknowledged outright that they have engaged in racist practices, or explained how they plan to stop. There aren’t many parents willing to stop arranging their housing around the pursuit of “good schools”—thinly veiled code for white schools—or wealthy people ready to admit the racial consequences of opposing higher taxes on investment earnings. After the nation’s so-called reckoning, to which those who claimed to have awakened brought PowerPoint presentations and brochures, few have stayed behind to fold and stack the chairs.

It is not true that, as the most exhausted among us sometimes assert, nothing has changed. But as the optimistic Myrdal saw in 1944, yet had a hard time putting bluntly, America is not about the business of doing things much differently. When the New Deal reoriented Americans’ relationships to their government, officials south of the Mason-Dixon Line made sure that most of the jobs done by Black Americans were excluded from the new Social Security system. Program administrators barred Black Americans from meaningful access to the homeownership and education programs that ensconced millions of white Americans in the middle class.

In his study, Myrdal found ample proof of Black ingenuity, creativity and grit, producing lives of multidimensional joy and peril. All that’s still there. But perhaps today’s list of dangerous inequities wouldn’t run quite so long or, in some cases, have come to envelop other groups, if sustained action had been taken in response to his findings—something he believed possible. “It is true the average white American does not want to sacrifice much himself in order to improve the living condition of Negroes,” he wrote. “But on this point, the American creed is quite clear and explicit.”

Myrdal died in 1987. He did not live to see the new and creative ways that Americans have developed of telling lies. And he was not immune to the same maladies. Myrdal was optimistic about the nation and dubious about whether Black Americans were equipped to function as full citizens.

I’m told that those of us who aren’t white—a growing share of Americans—can take heart in knowing that our maltreatment is being discussed at all. This is akin to a cruel warden demanding extra pay for services rendered. Those who live with the myriad consequences of inequality are, at this point, unlikely to be impressed by mildly uncomfortable chatter about race in America.

Many are, quite frankly, already busy finding meaning in the American creed, creating new possibilities and erecting work-arounds with the ingenuity and grit that have sustained them thus far. And as was evident in last summer’s protests and the fall’s election returns, Americans, but particularly Black Americans, have and will put in work to make a democracy of equals real.

Read more: Why John Lewis Kept Telling the Story of Civil Rights, Even Though It Hurt

The situation reminds me of the first time I was called the N word to my face—far from the worst moment that being Black in America has brought me, but an instructive one.

A few months before I began kindergarten, my parents emerged triumphant from their battle with banks, real estate agents and the opportunities available to Black people in the U.S. labor market. They bought their first home in a North Texas suburb so new that a wrong turn meant driving on a dirt road.

My parents grew up in the Jim Crow South. They knew how scary so-called economic anxiety can get when one group’s stranglehold on privilege ends. So they didn’t expect things to be easy in the new neighborhood. What mattered to me at the time: my sister and I quickly found friends. There were three white girls next door and a Black and white biracial brother and sister opposite us in the cul-de-sac.

When a new boy showed up—Chad, towheaded and in tube socks—we were glad to include him. He was one more person to make the day’s checkers tournament interesting and one more contender in our bike races to the end of the street and back. But when Chad lost, Chad got mad. Standing near the curb outside our house, he leaped off his bike after a race and said it: He was sick of playing with “stupid niggers.”

It was bad and everyone knew. When Chad hadn’t returned for his bike a half hour later, the Ross girls gathered a toolbox from our garage. With the help of our friends, we broke Chad’s bike down to its parts. Handlebars, pedals, tires, main body, screws and washers, all left in a pile. Chad—who presumed himself smarter and better; who said he wanted to play with us but didn’t like it when we won fair and square; who even as a child turned so automatically to that slur as soon as he saw that we, that day, beat him—would have to figure out how to get it all home. Later, Chad’s father, his son cowering behind him, rang our doorbell to demand that we apologize.

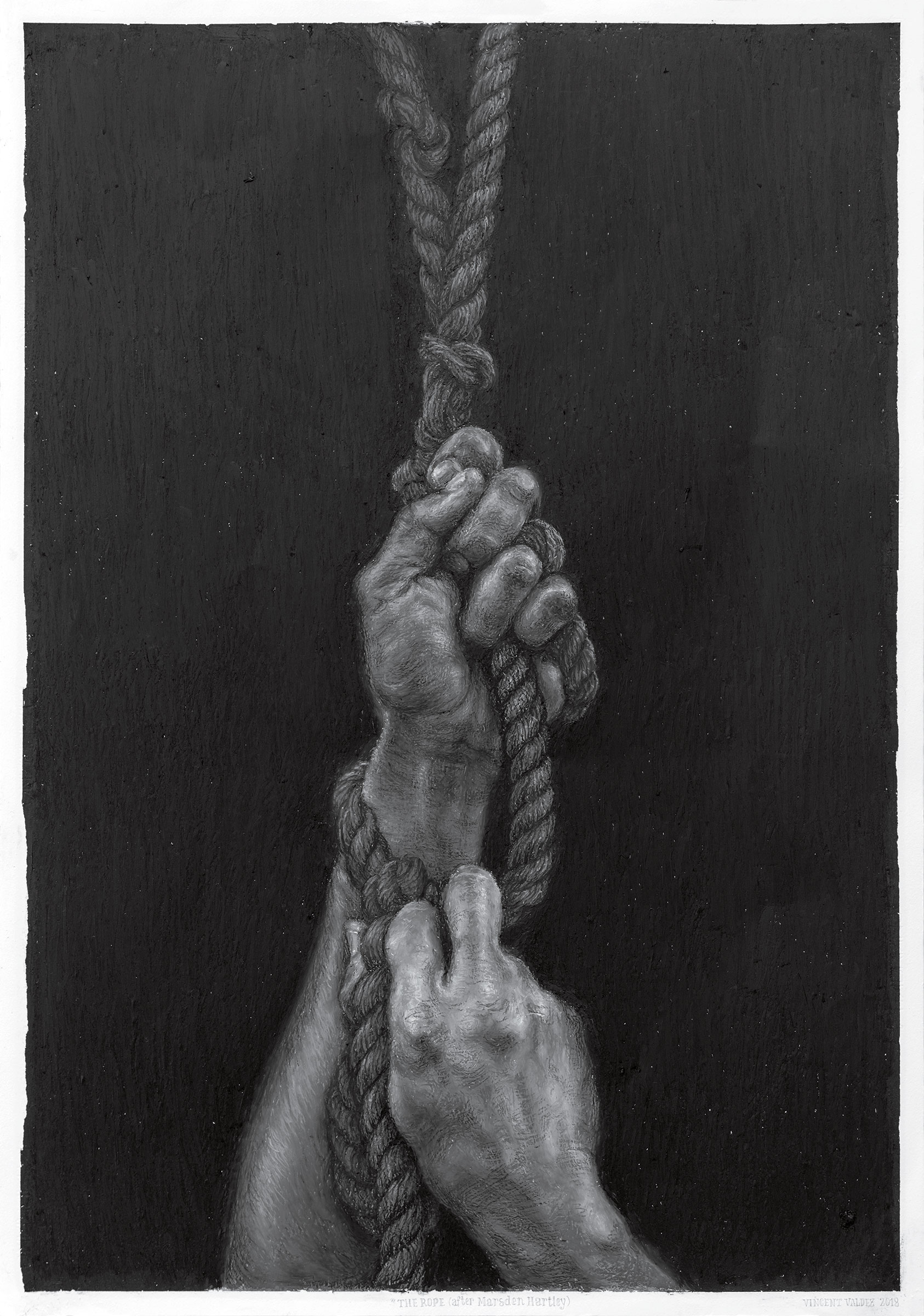

The experiences that accompany life in the body of a person of color are well documented. But even as the notion of white America’s inherent superiority is verbally rejected, very few are willing to use what power they have to shift the systems that have served them well. Some people who are used to winning are having trouble playing fair. But America should not expect people of color to apologize for disassembling the vehicles that support racial inequality.

The people out there with the screwdrivers and wrenches, trying to make the country into what it promised to be, are disproportionately people of color, particularly Black Americans. But if the suffering and loss of the past year is to have meaning, the work of private citizens cannot be enough. We must begin by holding to account those in power—especially the man in the White House.

The phrase talk is cheap is a truism for a reason. We have heard enough. Now let’s watch for what is done.

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness