Linda Brown, who died this week at 75 after a lifetime as a sometimes-reluctant national icon associated with the landmark desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education, became a public figure because of where she went to school. She was forced as a child to travel two miles across Topeka, Kans., to attend an all-black elementary school rather than going to the white school that was mere blocks from her home. It was that journey, and the obvious discrimination behind it, that drove her father to launch the lawsuit that culminated in the 1954 Supreme Court ruling that separate was inherently equal.

Historian and activist Mary Frances Berry, former head of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, had something in common with Brown. Berry made a similar trek across her home city of Nashville in the early 1950s, peering in the windows of the all-white school as she passed and marveling at how nice it looked inside. And she remembers seeing the newspaper come out with a headline announcing the decision in Brown.

“I said to my teacher, ‘Does that mean all the children will go to school together next year?’” she recalls. “She said to me, ‘Not so fast, Mary Frances, not so fast.’ I guess she was right.”

But, as the world remembers Linda Brown’s legacy, Berry points out that the “not so fast” narrative that surrounds the case is only part of the story. It’s true that the court’s decision that the ruling should be implemented “with all deliberate speed” did not in fact translate to quick or painless desegregation in schools or elsewhere; in fact, in more recent years, much of the progress that was made in American schools in the wake of Brown was erased. As the integration pioneer James Meredith, who broke the racial barrier at the University of Mississippi, put it to TIME this week, the decision “did not deliver what it promised.”

“Brown was important not because it desegregated schools, because the schools today are segregated. We call it ‘racially isolated’; that’s a euphemism. Most black kids and brown kids go to schools where most of the kids are black and brown,” Berry says. “If we think we have to test Brown’s importance by whether it desegregated the schools permanently, the answer would be no.”

But, Berry argues, the overall impact of the case is much broader than it would appear to be if one were looking at school integration data only.

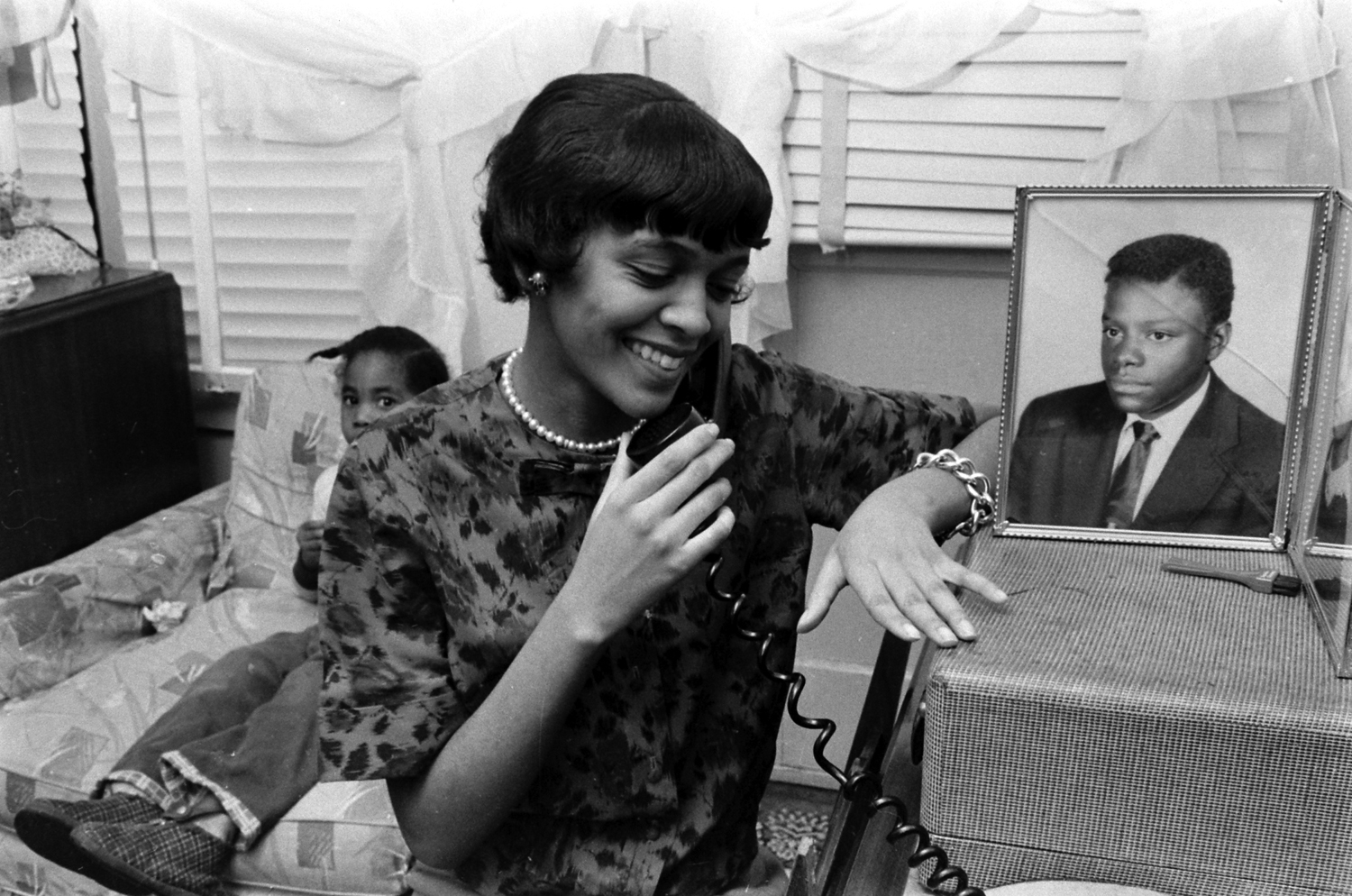

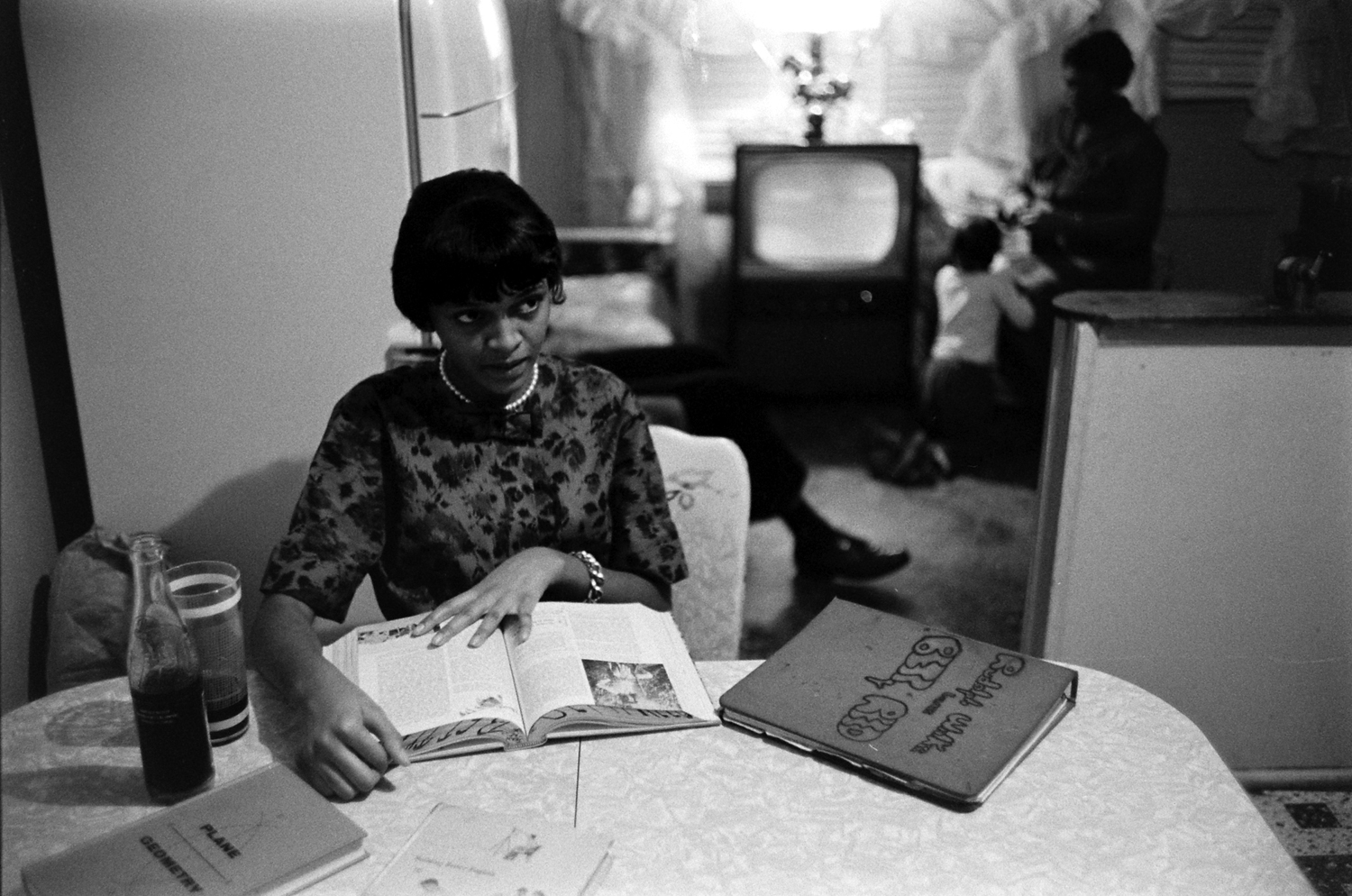

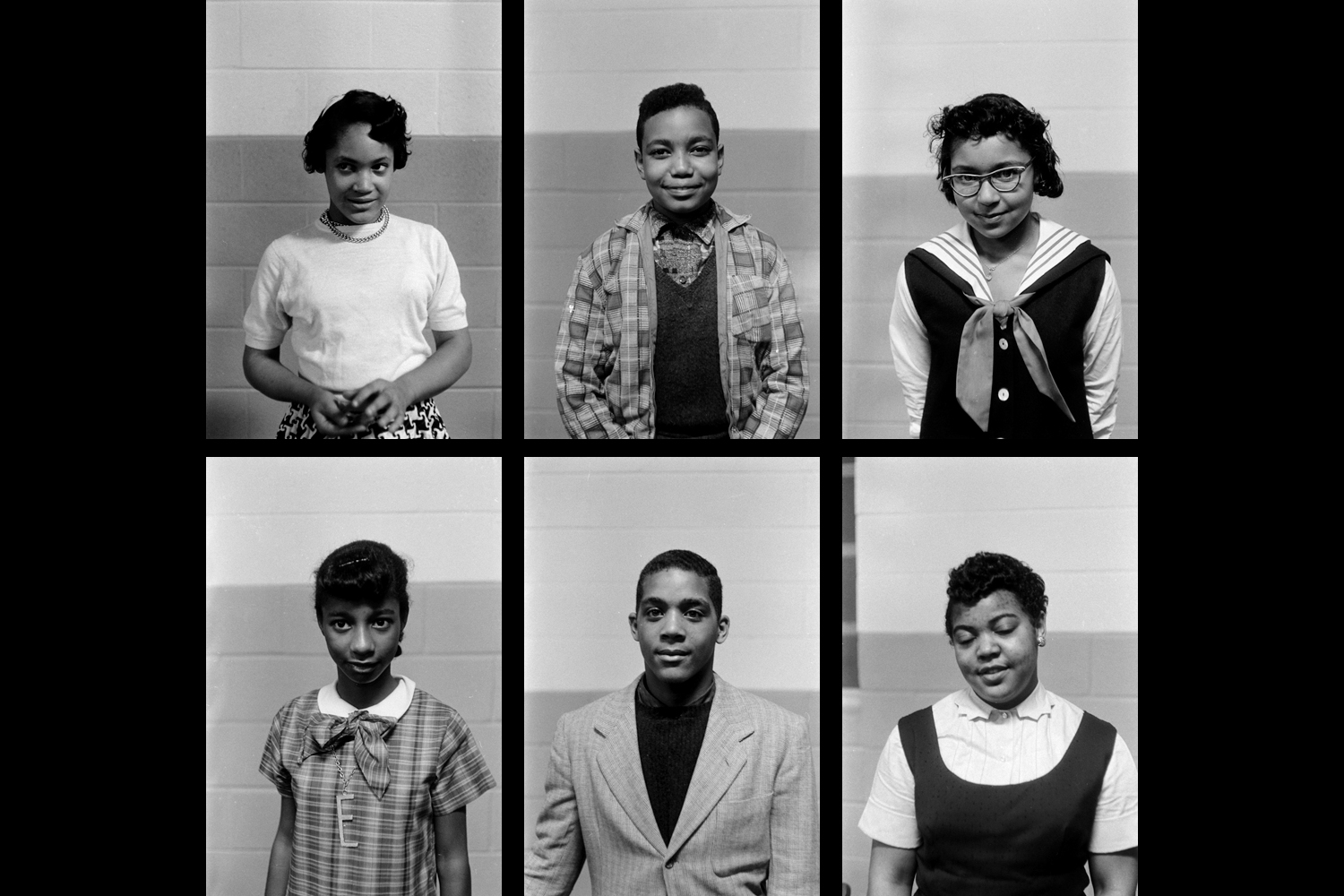

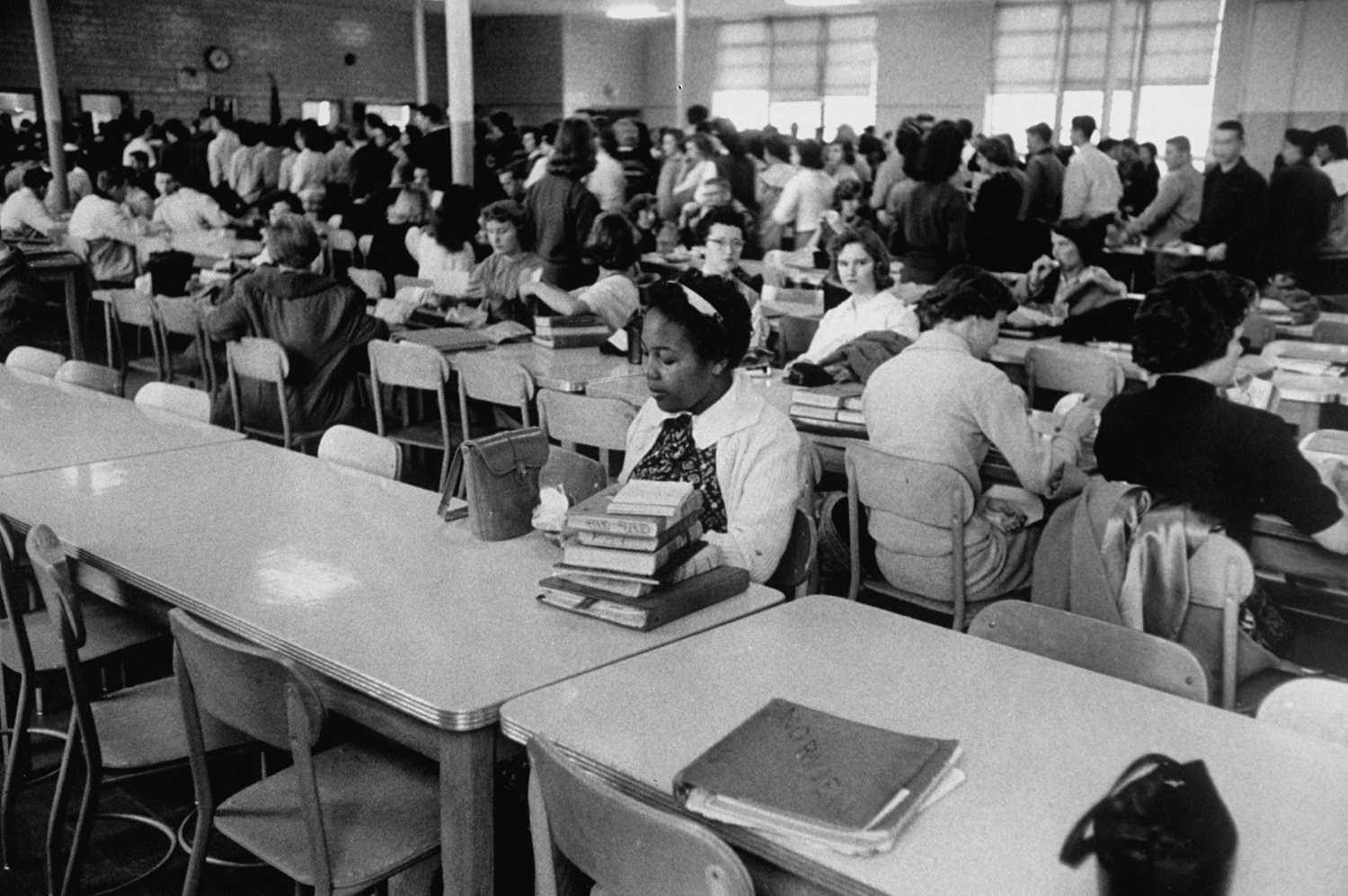

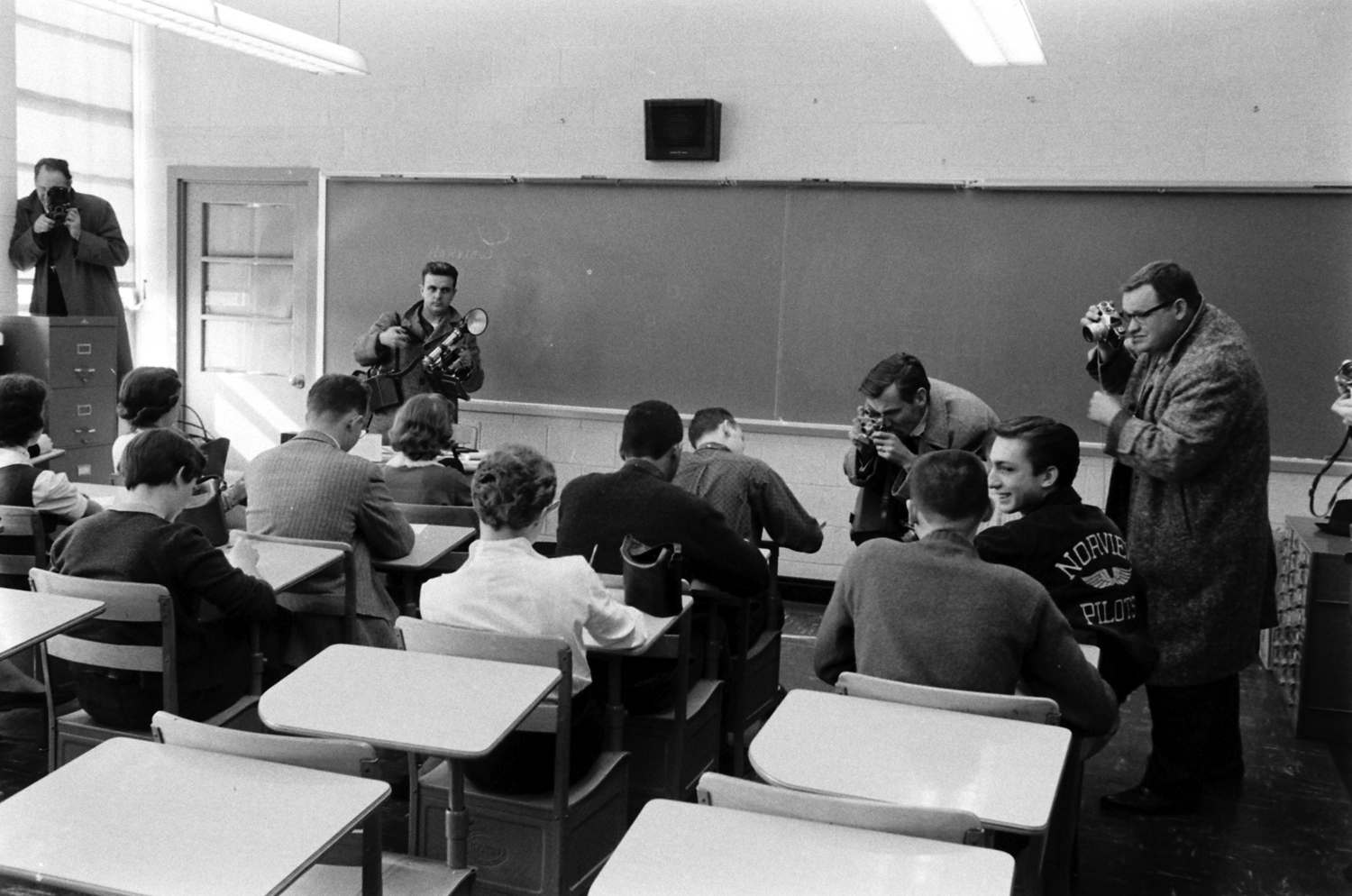

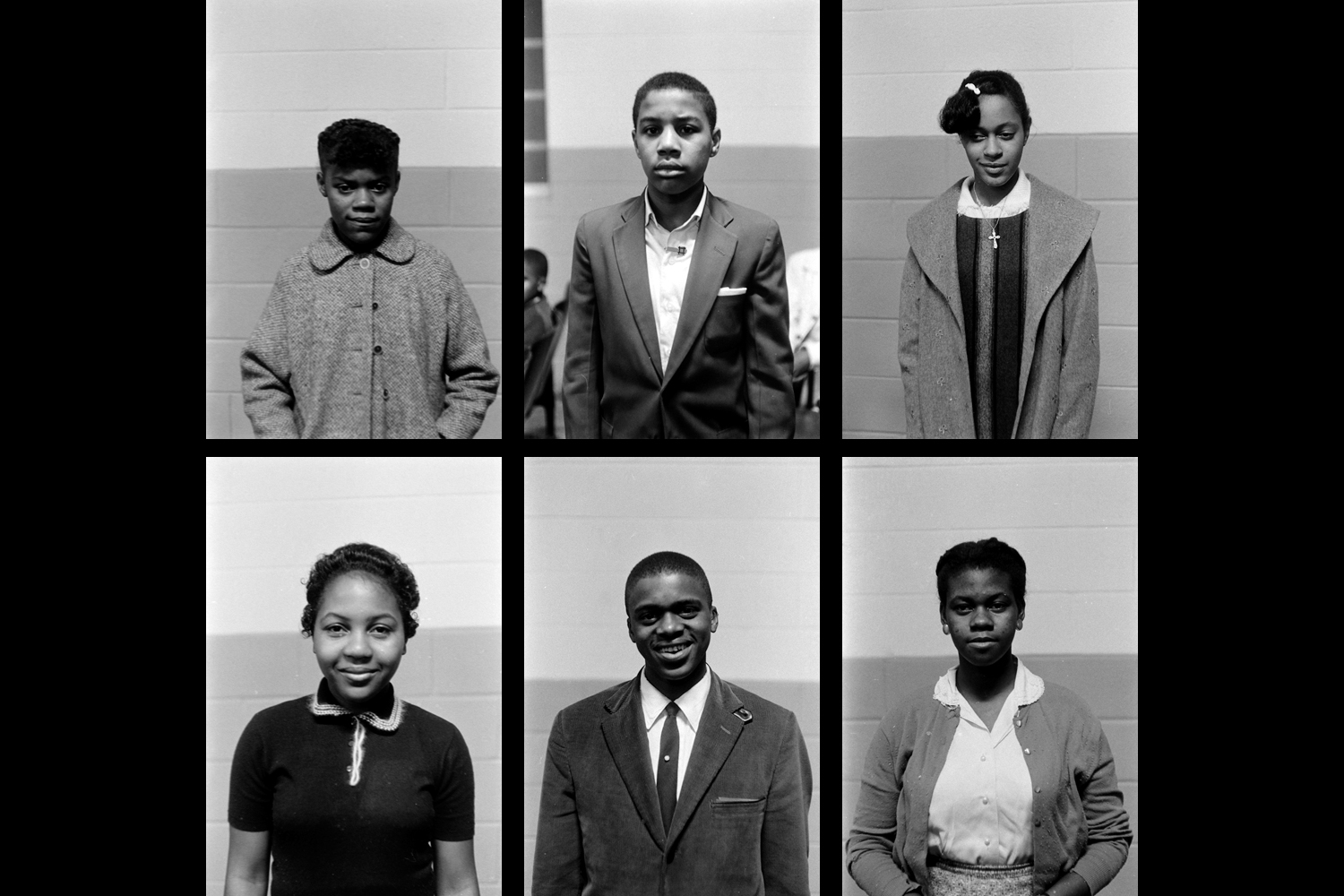

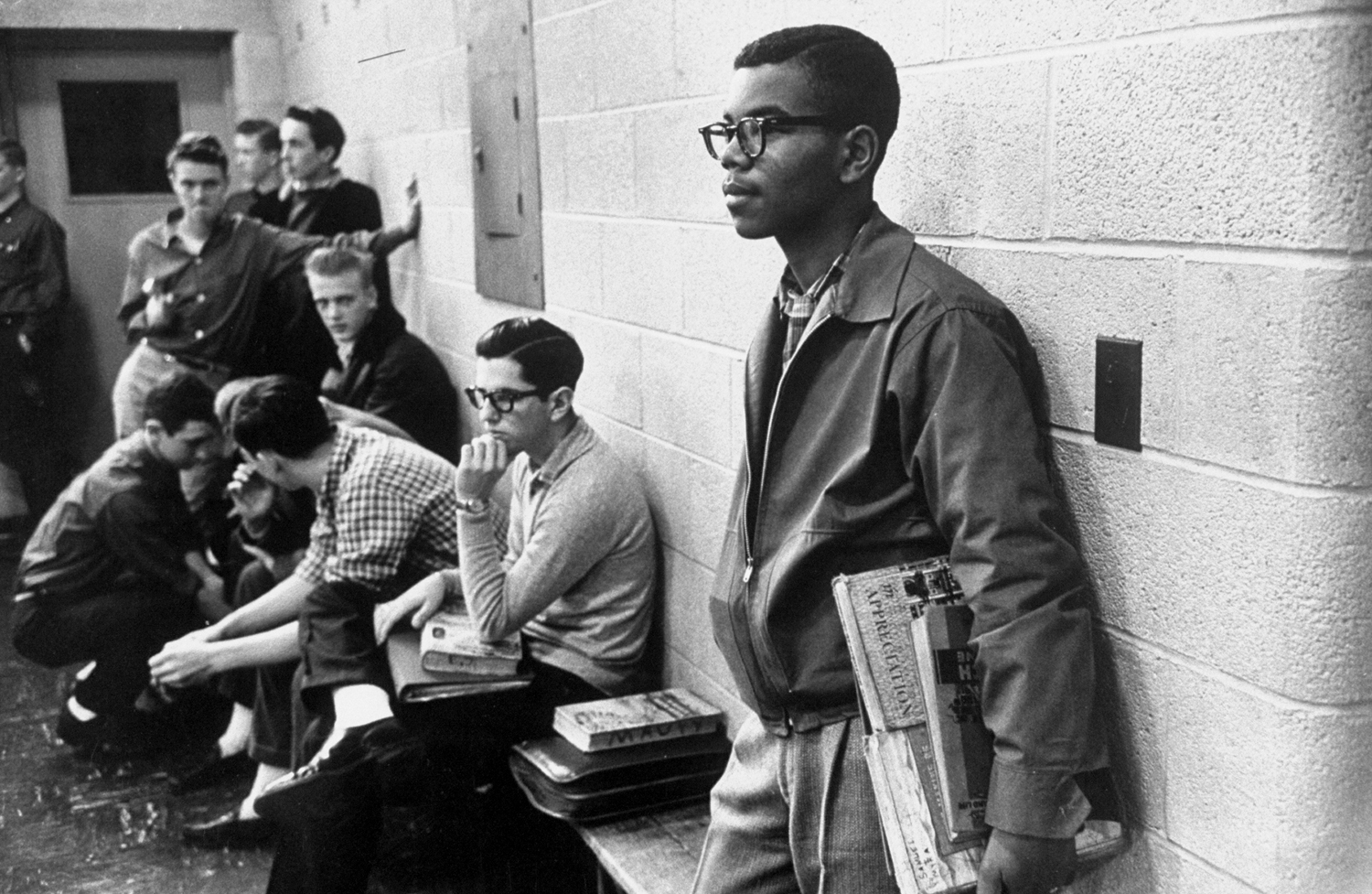

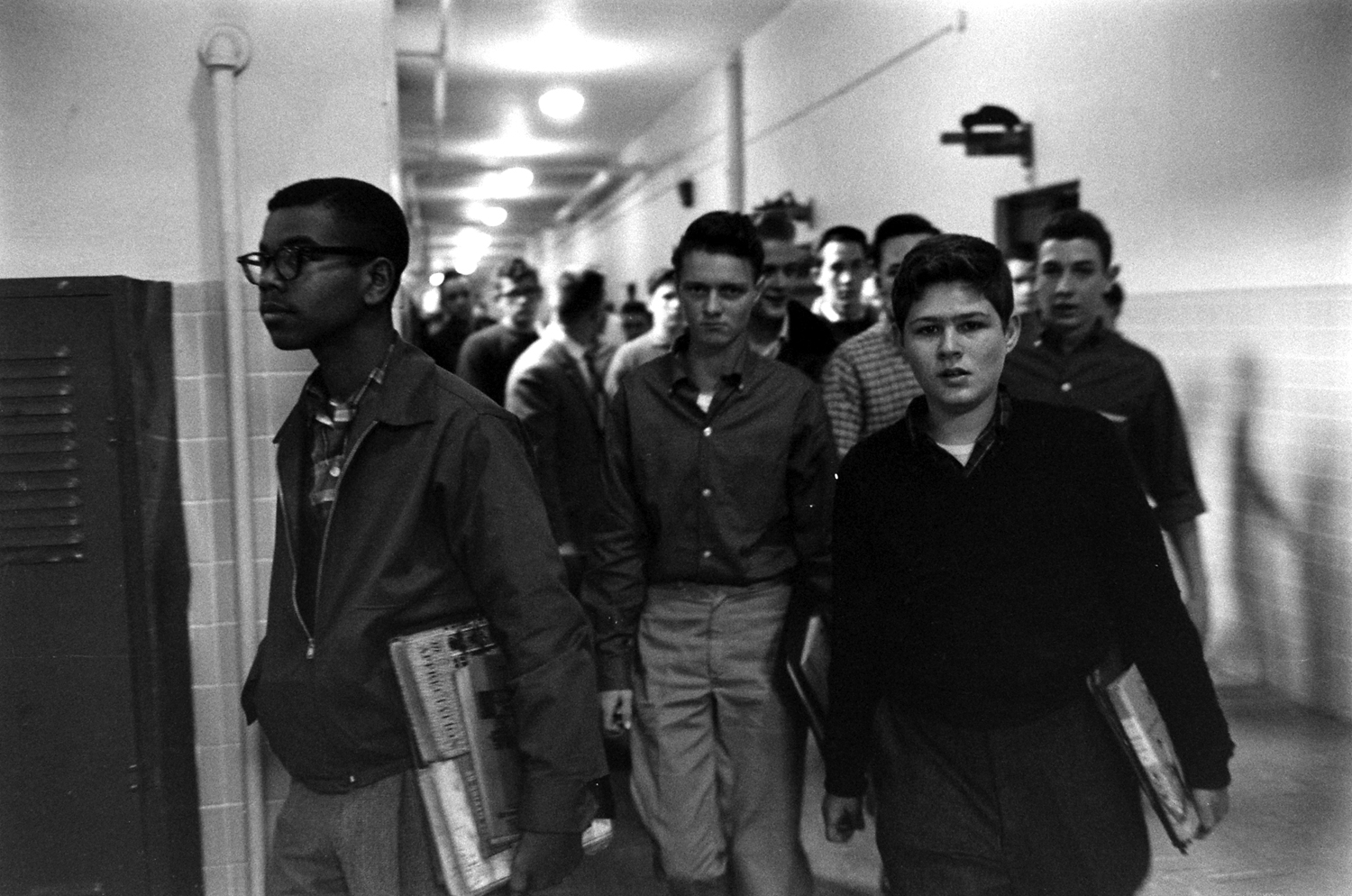

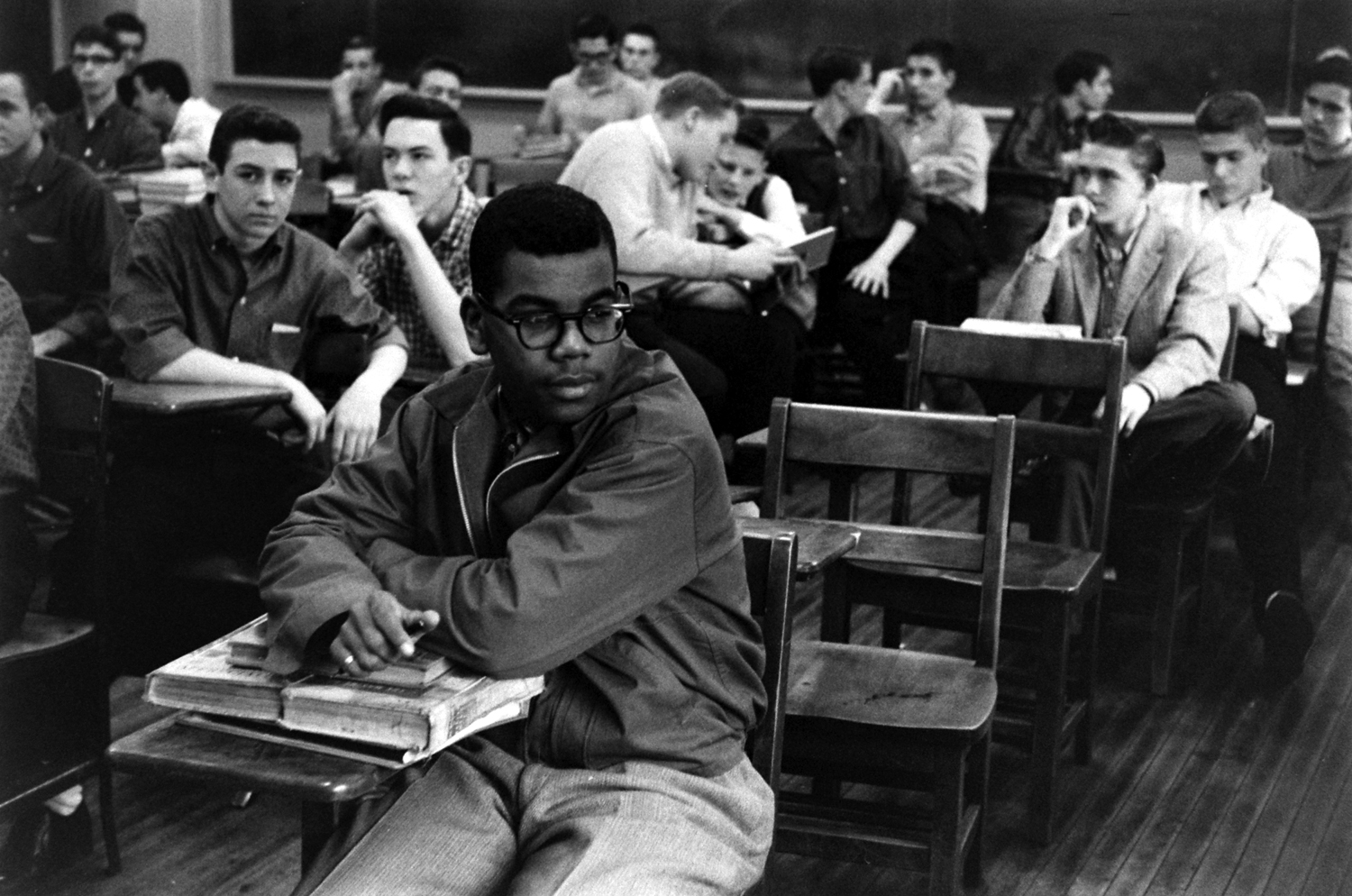

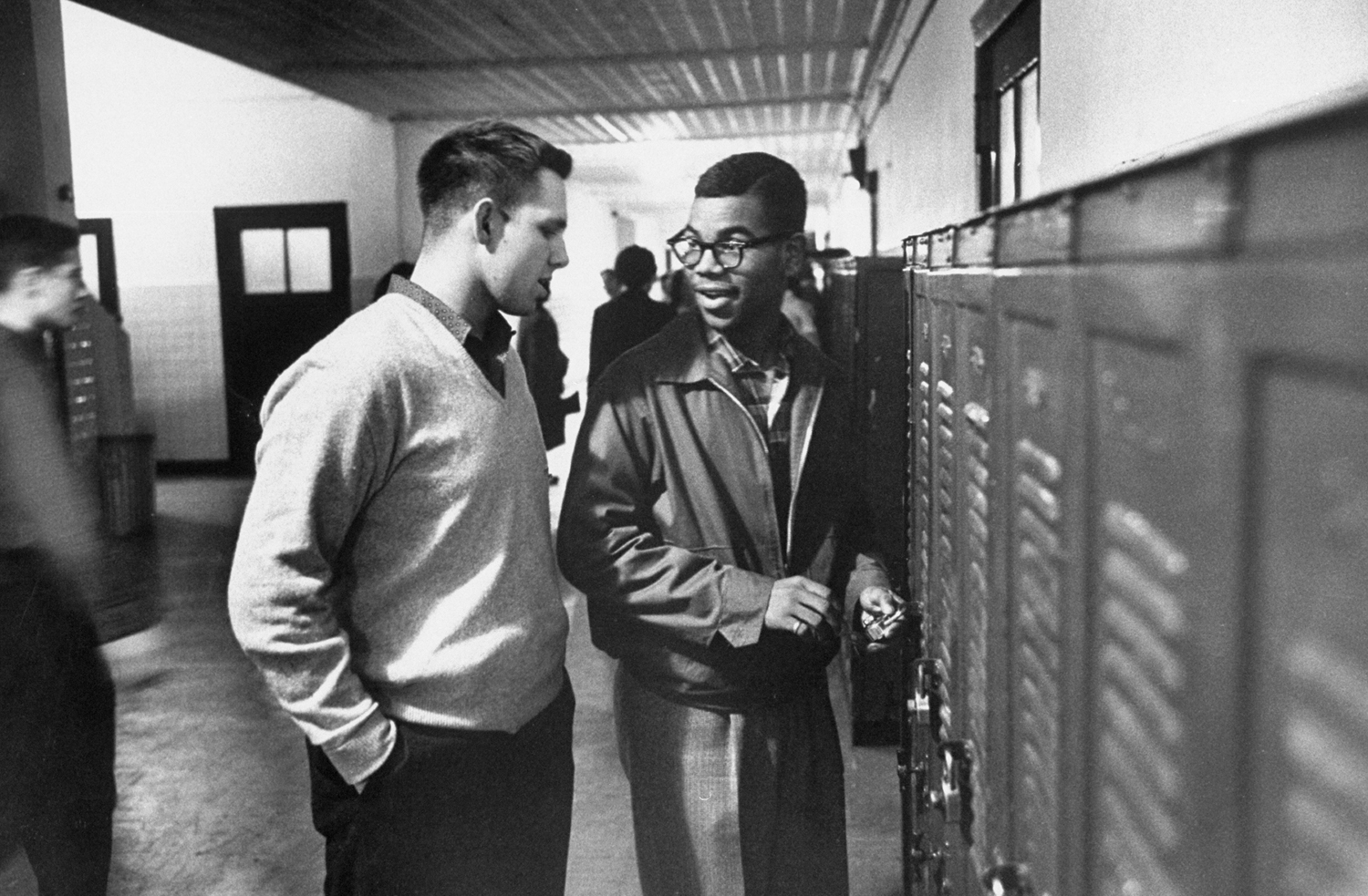

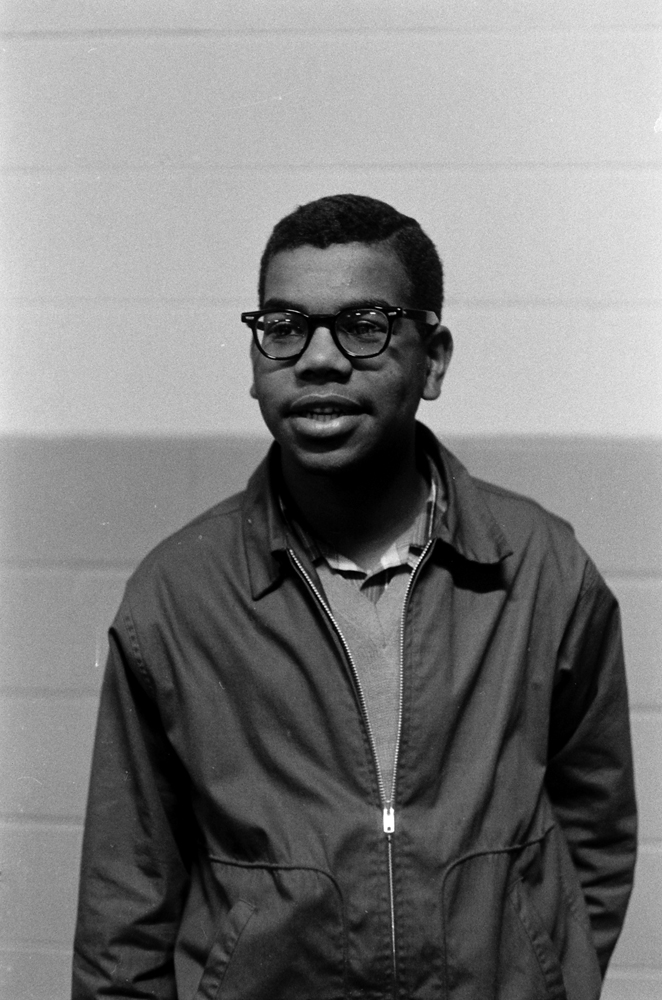

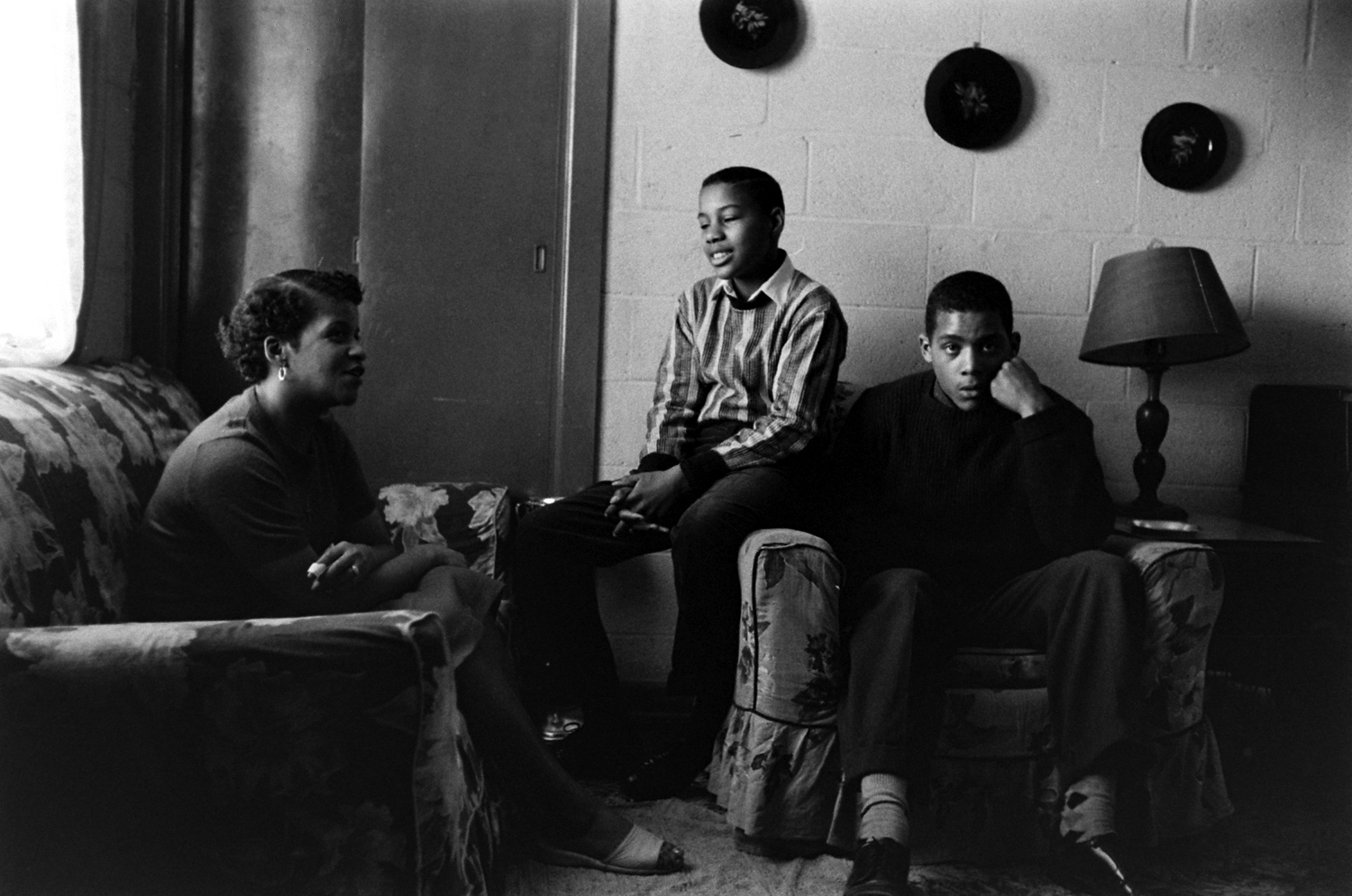

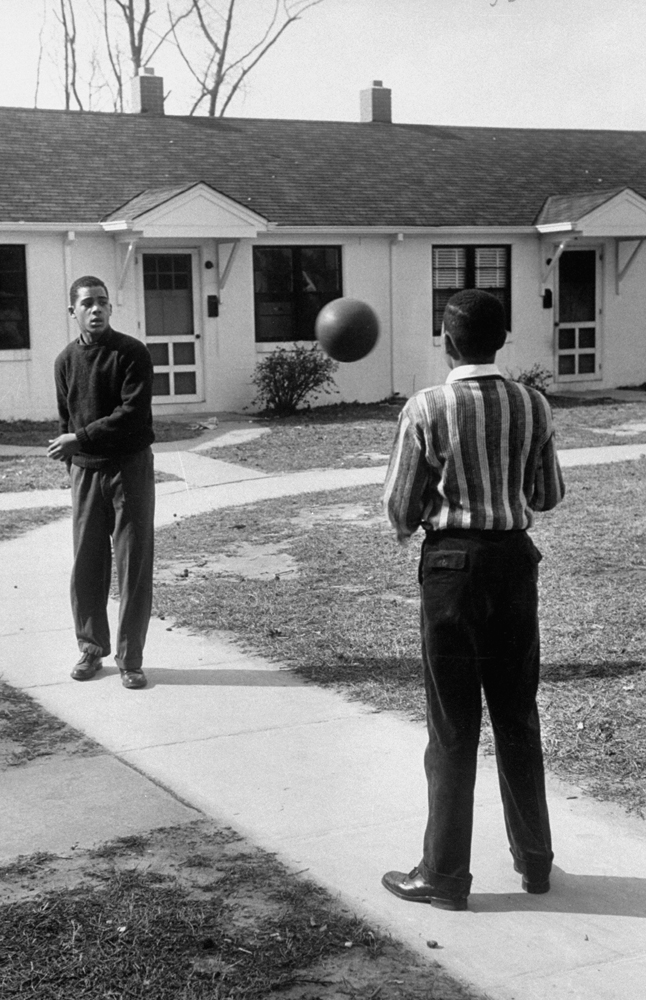

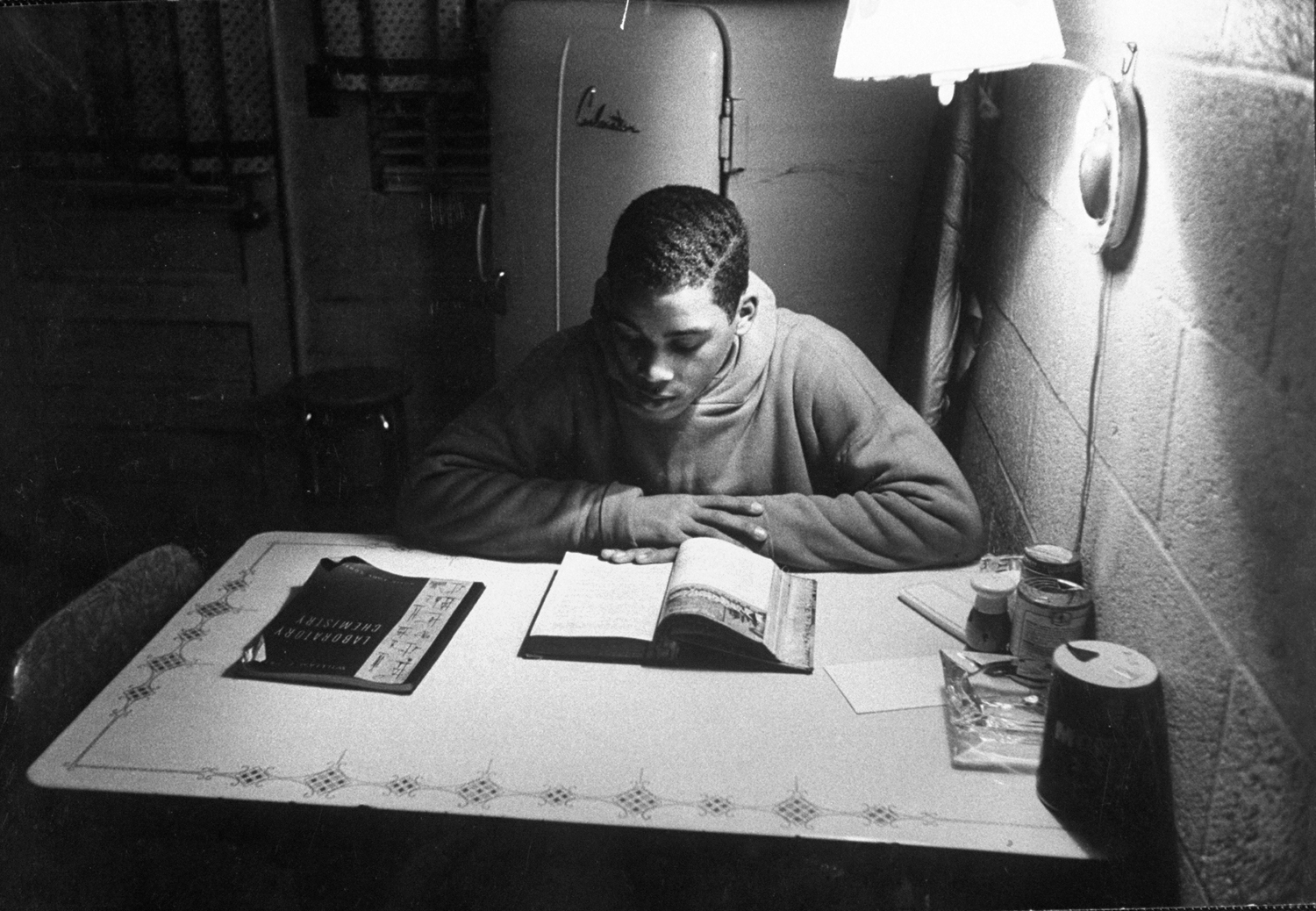

After ‘Brown v. Board of Education’: Portraits of Integration, Virginia, 1959

For one thing, even as segregation remains the practical truth in many parts of the country, a huge amount of the stigma attached to the idea of separate education—the feeling of inequality that was inherently attached to the idea that school segregation was necessary—was lifted by the case.

Secondly, it was only about a year after the Brown ruling that Rosa Parks made her stand and thus precipitated the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott, which in turn led to the 1956 Supreme Court case Gayle v. Browder. In that case, as Berry points out, the justices affirmed a lower court decision that segregated transportation was unconstitutional, based in part on the precedent that had been set by Brown. The Brown decision also served as a legal underpinning for civil rights laws that would be passed in the decade that followed.

Thirdly, the reaction to the case—the harsh stand many took against integration, even in the face of federal enforcement—galvanized a movement to demand equality.

“The hostility to implementing Brown led many of us, young people like me and others, to be willing to engage in nonviolent direct action,” Berry says. “I think it was absolutely crucial not just in schools but for the whole fabric of American life.”

That massive impact is why it’s all the more notable that the promise of Brown has not truly been fulfilled in American schools, even though data show that—on top of the moral imperative for equality—integration leads to better educational outcomes. Among the myriad ripples caused by Linda Brown’s childhood struggle, Berry says, education is ironically “the great missing piece.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com