On the evening of May 2, Anna Wintour will take her place at the top of the carpeted steps leading into New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Wintour, now Condé Nast’s global chief content officer as well as the global editorial director of Vogue, has been hosting the Met Gala for nearly 30 years. She is always happy on this night, a year in the making—but this is still work. And that means every detail must be perfect.

Former Met Gala planner Stephanie Winston Wolkoff—also a former adviser to Melania Trump—describes Wintour as “militant” during the party each year. “Where is everybody? It’s time,” Wintour says to her team. “Where are they? Can you tell me where they are?” The Vogue staff knows. Every guest has a prearranged arrival time, and Wintour’s people know what cars they’ll arrive in, if they’ve left the house, what they’ll be wearing, and if they’ve broken a zipper along the way that needs to be fixed.

Planning the gala typically begins in the early fall with 7 a.m. meetings at the Met every four to six weeks. In past years, the museum’s team has tried to keep the costs and footprint down, though Vogue has pushed the party to become the sort of thing that demands a 4,000-lb. floral arrangement. As with her assistants, Wintour has had a habit of not learning the names of some at the Met that she has worked with—year after year—to plan the party, a former staff member recalls. Sometimes she addresses them as “you” and points; other times she calls them variations on their names. Her directives have often been so absurd the Met team just laughs them off. According to two people familiar with her remarks, at one point Wintour gave them the impression that she found the Temple of Dendur ugly and said she wanted to board it up, but ultimately compromised and simply had Katy Perry’s stage erected in front of it. (“Anna has been in the public eye for 30 years, speaks regularly about her life and work, and yet she has often found herself in a position in which others claim to be telling her story,” a spokesperson for Vogue wrote when asked to comment on this piece. “Anna: The Biography was written without Anna’s participation.”)

At dinner, Wintour notices every detail. When Kim Kardashian wore a custom latex Thierry Mugler dress that redefined tight to the camp-themed party in 2019, Wintour kept saying to Lisa Love, a personal friend and former longtime West Coast director of Vogue, “Can you please tell her to sit down?” Love had to explain that, actually, Kardashian physically could not sit.

“The only thing about the Met that I wish hadn’t happened is that it’s turned into a costume party,” designer Tom Ford says. “That used to just be very chic people wearing very beautiful clothes going to an exhibition about the 18th century. You didn’t have to look like the 18th century, you didn’t have to dress like a hamburger, you didn’t have to arrive in a van where you were standing up because you couldn’t sit down because you wore a chandelier.” (The planners often have to provide backless chairs for guests wearing gowns that won’t fit into regular seats.)

But Wintour loves the over-the-top looks. “It’s that English part of her. She loves a dress-up party,” Love says.

Read More: Lady Gaga Outdid Herself on the 2019 Met Gala Red Carpet

A night of excess and exhibition, the Met Gala is where Wintour flaunts her dominance over an industry that’s predicated on the understanding that there is an “in” and an “out.” In Wintour’s world, people occupy those distinct buckets. Some are always “out”—low-performing assistants, the Met’s event planners who tell her she can’t hang a dropped ceiling over a priceless statue, the Hilton sisters. Some, whose success, power, creativity, and beauty are undeniable, are therefore always “in” (Ford, Serena Williams, Roger Federer, Michelle Obama). Some begin as “in” and get moved to “out” (the late André Leon Talley). Others begin as “out” and become “in” (Kardashian).

Wintour’s longevity as a fashion mega-influencer in a business that is fickle by design is unmatched, and the Met Gala is the ultimate manifestation of her power. But her selection of who’s in and who’s out—who gets her endorsement in the industry, and therefore who gets fast-tracked to success—extends far beyond the guest list.

“As much as she loves a person who has talent,” Talley said before his death, “if she does not love you, then you’re in trouble.”

The Met Gala started as a fundraiser for the Costume Institute in 1948. Called the party of the year, it was a midnight supper for New York society. Wintour began planning it in 1995, a period when the museum wanted to reignite buzz around the Costume Institute, and turned it into an event that had representatives for celebrities calling and asking for invitations. Many were repeatedly denied. The celebrity guest list, carefully curated over the years by Wintour, led the Met Gala to be dubbed the “Oscars of the East Coast,” but that moniker no longer fits: in terms of the red carpet, the Met Gala now surpasses the cultural significance of the Oscars.

The event has not been without controversies, which have only increased buzz around the annual tradition. In 2018, Scarlett Johansson walked the “Heavenly Bodies” carpet in one of the more demure evening gowns of the night, by Marchesa, but still caused quite a spectacle. It was the first major red-carpet appearance for the label since designer Georgina Chapman’s husband, Harvey Weinstein, had been brought down in a defining story of the decade.

On Oct. 5, 2017, the New York Times had published Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey’s report about Weinstein’s long history of paying off sexual harassment and assault accusers. It was followed five days later by an explosive story in the New Yorker by Ronan Farrow, which contained additional damaging accounts of sexual assault and harassment by Weinstein.

Weinstein had long been a known bully, but someone working closely with Wintour at the time said there was no indication that she knew about the allegations detailed in the Times and the New Yorker. Nonetheless, her loyalty to certain people ran deep, and she and Weinstein seemed to have a relationship that went beyond a typical industry friendship. Weinstein had feverishly courted her favor since the mid-’90s, desperate for both her approval and for Vogue to cover his films. Their decades-long relationship was why Wintour repeatedly made the allowance—afforded to no one else—for him to split the cost of a table at the Met Gala with Tamara Mellon, the Jimmy Choo co-founder. And why he was among a small group of guests Wintour made sure were discreetly pulled out of the line queued up before the red carpet so they didn’t have to wait. It also seemed to explain why Wintour had to be talked out of having lunch with Weinstein at his invitation after the Times story broke (to avoid the possibility of being photographed together). And presumably why it took a full eight days after the Times story came out for her statement denouncing his behavior to appear in the paper.

“Behavior like this is appalling and unacceptable,” she told the Times. “I feel horrible about what these women have experienced and admire their bravery in coming forward. My heart goes out to them, as well as to Georgina and the children. We all have a role to play in creating safe environments where everyone can be free to work without fear.”

Before she issued that statement, Wintour cut off contact with Weinstein and set up a call with his wife, whose fashion career she had been supporting for more than a decade. The day after the gala, on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert, Wintour commented directly: “Georgina is a brilliant designer, and I don’t think she should be blamed for her husband’s behavior. I think it was a great gesture of support on Scarlett’s part to wear a dress like that, a beautiful dress like that, on such a public occasion.” A dress that Wintour, as she does for most of her guests, had likely approved.

Over the decades, Wintour has seemed to view it as her job to rehabilitate her favorite designers felled by scandal. When John Galliano, one of her all-time favorite designers, was fired from Christian Dior after being filmed spewing an antisemitic tirade at a bar in 2011—saying, “I love Hitler”—Wintour sprang into action. Before she managed to place him in a job at Maison Martin Margiela (now Maison Margiela), she was the one who called Parsons to ask if Galliano could have a faculty appointment. The school was prepared to give him a three-day class to teach, but was forced to cancel it after a wave of backlash.

Her move to rescue Marchesa was also controversial. In one essay, The Cut’s then-editor-in-chief Stella Bugbee wrote, “This is not a designer with Galliano-level talent. Chapman’s career was funded and made possible by affiliation with her powerful husband and his equally powerful fashion-editor friend. Now that editor has ensured her return to the very red carpet where so many actresses were pushed to wear her dresses, despite her affiliation with a known bully and abuser. This is how Anna Wintour chooses to use her power.”

Wintour’s alliances with powerful men came under further scrutiny when, following Weinstein’s downfall, Vogue’s favored photographers Mario Testino and Bruce Weber were also accused of sexual misconduct as part of the #MeToo movement. This time, however, Wintour took a different course of action, announcing that month that, despite them being her personal friends, Vogue would stop working with them right away.

The ability to make decisions about who matters is the great source of Wintour’s power—along with her ability to put people in the “out” bucket in an instant. “If you get frozen by her, that’s it. She’s a Scorpio, you’re done,” says Love. “It’s that cold.” It’s why, with Wintour in control, fashion designers, writers, editors, photographers are never safe. What if they get frozen out?

Designer Isaac Mizrahi enjoyed Wintour’s support for three decades, even though it seemed to wax and wane as the years went on. Mizrahi was forced to close his label in 1998 after he lost financial backing; though he eventually relaunched, he wrote in his memoir I.M. that he was left “jealous of others [Anna] paid attention to.” Finally, at one of his shows in the early 2010s after the relaunch, he was waiting for Wintour to take her front-row seat. After 20 minutes, it became clear she wasn’t coming, and they let someone else have it. “It was a blow,” he wrote. “I took it as a sign that my years as a couturier were waning.”

Her interest in designers can be painfully fleeting. Zang Toi received her support beginning in 1989. “She fell in love with what I do. I was the first Asian designer that was championed by Anna Wintour,” says Toi, who is Malaysian. One of Wintour’s market editors came to see his very first collection, which included just 13 pieces. She took Polaroid pictures to take back and show Wintour, and the magazine ended up borrowing three looks. They sent two back and asked to keep the third, a bright-orange and pink baby-doll dress, which they photographed in Morocco for a story about young designers in the February 1990 issue.

Toi’s clothes started appearing in the magazine regularly. Wintour came by herself to Toi’s 200-sq.-ft. studio to see his second collection, taking notes the whole time. He was grateful for Wintour’s support. In fact, he found her warm. “She gave us great press in the first year. That cemented my reputation,” says Toi, who started attracting a clientele of very wealthy, private-jet-owning women. Wintour even personally sponsored Toi for a competition for young designers in 1990, which he won.

Their friendly relationship continued through the mid-90s. He recalled her always coming to see his collection a few days before his show, and she never told him to do anything to his clothes. One day, however, she couldn’t make it. Two members of her team went to see Toi’s collection, but he missed their visit, which had been rescheduled for a time he was supposed to be at lunch with an editor from Harper’s Bazaar.

When he got back from lunch, his assistant told him, “They loved the collection, they thought it was beautiful, but they told me two dresses were not very Vogue. Don’t show them.” Toi didn’t think anything of it. He had around 45 looks in the show; so what if Vogue didn’t like two of them?

Toi said Wintour didn’t attend his show that season, but Vogue had requested seven or eight front-row seats. Toi left the offending dresses in the show. From then on, he couldn’t get Wintour or her team to come to his shows or to see his collections in his studio. The last time the two saw each other was at a Bill Blass fashion show around 10 years after Toi had fallen out of favor. Toi had been stopped by reporters when Wintour appeared. She looked at him for two minutes, saying nothing, and then walked off with her bodyguard.

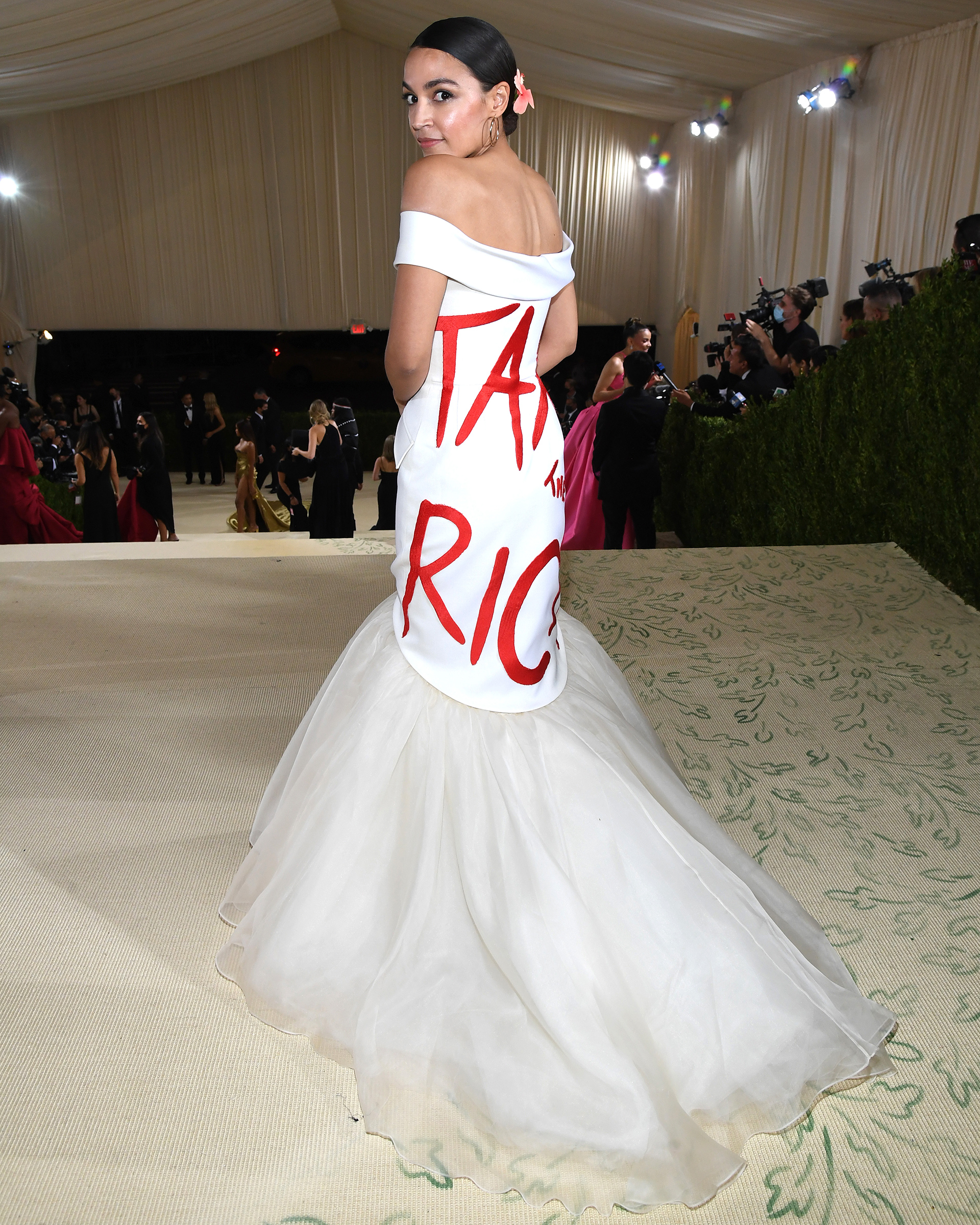

Anyone who attends the Met Gala this year will know that they are, at least for now, “in.” But being blessed by Wintour does not always translate to positive feedback outside of the industry. Last year, U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez attended for the first time, wearing a white gown by Aurora James that read “TAX THE RICH” in red on the back. For a politician whose every move draws debate, entering Wintour’s world, even just for a night, stirred up a swarm of critics, among them New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd, who wrote, “A.O.C. wanted to get glammed up and pal around with the ruling class at an event that’s the antithesis of all she believes in, a gala that makes every thoughtful American feel like Robespierre …”

It’s a sentiment that echoes how people feel about exclusionary practices across every category of life in America. In 2020, with social justice protests sweeping the globe, Wintour’s leadership of Vogue, particularly practices that led to a decades-long lack of diversity in its pages and on her staff, came under harsh scrutiny. On June 4, 2020, she sent her staff an email—quickly leaked to the New York Post’s Page Six—in which she confessed, “I know Vogue has not found enough ways to elevate and give space to Black editors, writers, photographers, designers, and other creators. We have made mistakes too, publishing images or stories that have been hurtful or intolerant. I take full responsibility for those mistakes.” Less than a week later, the New York Times published an article headlined “Can Anna Wintour Survive the Social Justice Movement?”

While there are those who think she should be fired or forced to resign, Wintour’s influence remains profound and unmatchable. She ended the disastrous year of 2020 with a promotion, announced in mid-December, to Condé Nast’s chief content officer, giving her oversight of all magazine brands, including the New Yorker and every international title. It seemed that no amount of bad press could shake her ascendancy. The mere mention of Wintour’s name remains enough to prevent advertisers from pulling money from Condé Nast magazines. Her phone call is all it takes to get a brand to sponsor a museum exhibit for millions of dollars. She is, in a capitalist society, exactly the kind of person a company like Condé Nast wants to keep at all costs, no matter how exclusionary her leadership style has been.

At 72 years old, Wintour surely has a plan for her exit from Condé Nast and for her future—but, aside from telling friends maybe she’ll do something where she’s being paid for her advice instead of giving it away for free, she hasn’t told them what it is. Sally Singer, who worked for Wintour for nearly 20 years, explains Wintour’s vision for Vogue, which perhaps mirrors the one she had for herself. “There was never an idea that Vogue was an editorial project alone,” she says. “It was an intervention into the fashion world.”

Wintour has built her own kingdom. And the world’s most beautiful, most powerful people are living in it. The rest are just looking on.

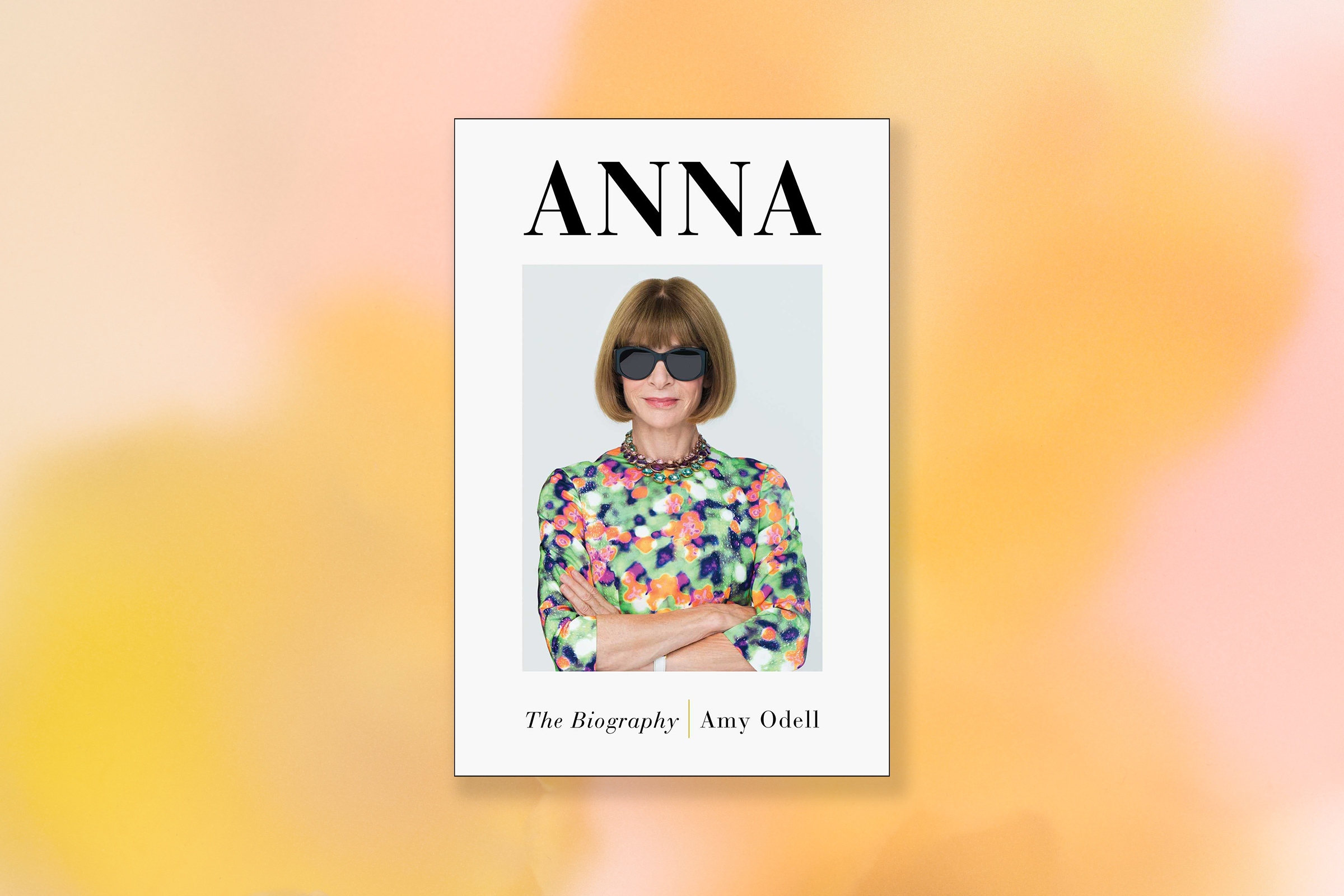

Excerpted from Anna: The Biography by Amy Odell. Copyright © 2022 by Amy Odell. Reprinted by permission of Gallery Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Home Losses From L.A. Fires Hasten ‘An Uninsurable Future’

- The Women Refusing to Participate in Trump’s Economy

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Dress Warmly for Cold Weather

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: No One Won The War in Gaza

Contact us at letters@time.com