This post was originally published in 2020. It's been updated to reflect the passage of time since World War II ended.

Movies based on true stories are a special breed of entertainment. We know better than to believe every detail or line of dialogue—movies are always a fiction in the broad sense—and that filmmakers who are dealing with real-life events need to take liberties. They might have to guess what certain encounters might have been like, or imagine dialogue in a situation of which there’s no record. Timelines are abridged; the order of events may be shuffled; supporting figures may be melded into a single character. And yet such a film also demands our trust. We may want to believe, even when we know we shouldn’t. Sometimes our skepticism and our awe have to walk hand-in-hand.

But a vivid, enveloping film can draw us close to the spirit of an event or a person in ways that make us want to expand our view. Sometimes we’re drawn to the library or bookstore, so we can read more about what really happened. And movies based on true stories put us in touch with the past in a visceral way. To see cities and towns recreated as they were 20, 50 or 100 years ago, to look at the clothes people wore, to hear patterns of speech that have since become outmoded: all of these things remind us that the past was a real place, peopled with human beings who cared about the same things we do, who faced challenges that nearly broke them and who found delight in the same joys we ourselves treasure. Each of us can live only one life, but movies that draw on history are windows into the selves that we might have been, had we been born in another time or place or circumstance.

Following is our list of the top 10 movies based on a true story, as chosen by TIME staff and a select group of historians. In order to qualify, the central story in a film must be at least inspired by a real story that happened to real people—not just a fictional story set against a real backdrop—and a central character based on a real person must do things that his or her real-life counterpart actually did. Heroes of investigative journalism, bank robbers and mob informants and gunslingers, ordinary citizens who fought for justice: These people can come to seem more real to us through movies. Their lives may be very different from our own, yet the movie screen opens a portal between us. And the more we learn about them, the more we want to learn. — Stephanie Zacharek

Methodology

We began by creating a pool of 70 contenders: every movie that met our own “based on a true story” standard and appeared at the time of the survey on the IMDB top 100 movies list, IMDB’s list of popular movies based on a true story, the AFI top 100, the Rotten Tomatoes top 100 or the All-TIME 100 Best Movies list. Ten TIME staffers and ten historians then ranked each of the 70 films on a scale of one to five—based on preference, not accuracy. After disqualifying movies that had been seen by fewer than half of the respondents, as well as movies with overwhelmingly split votes (i.e. all fives and ones), these are the films with the highest average scores. Survey design and analysis by Emily Barone.

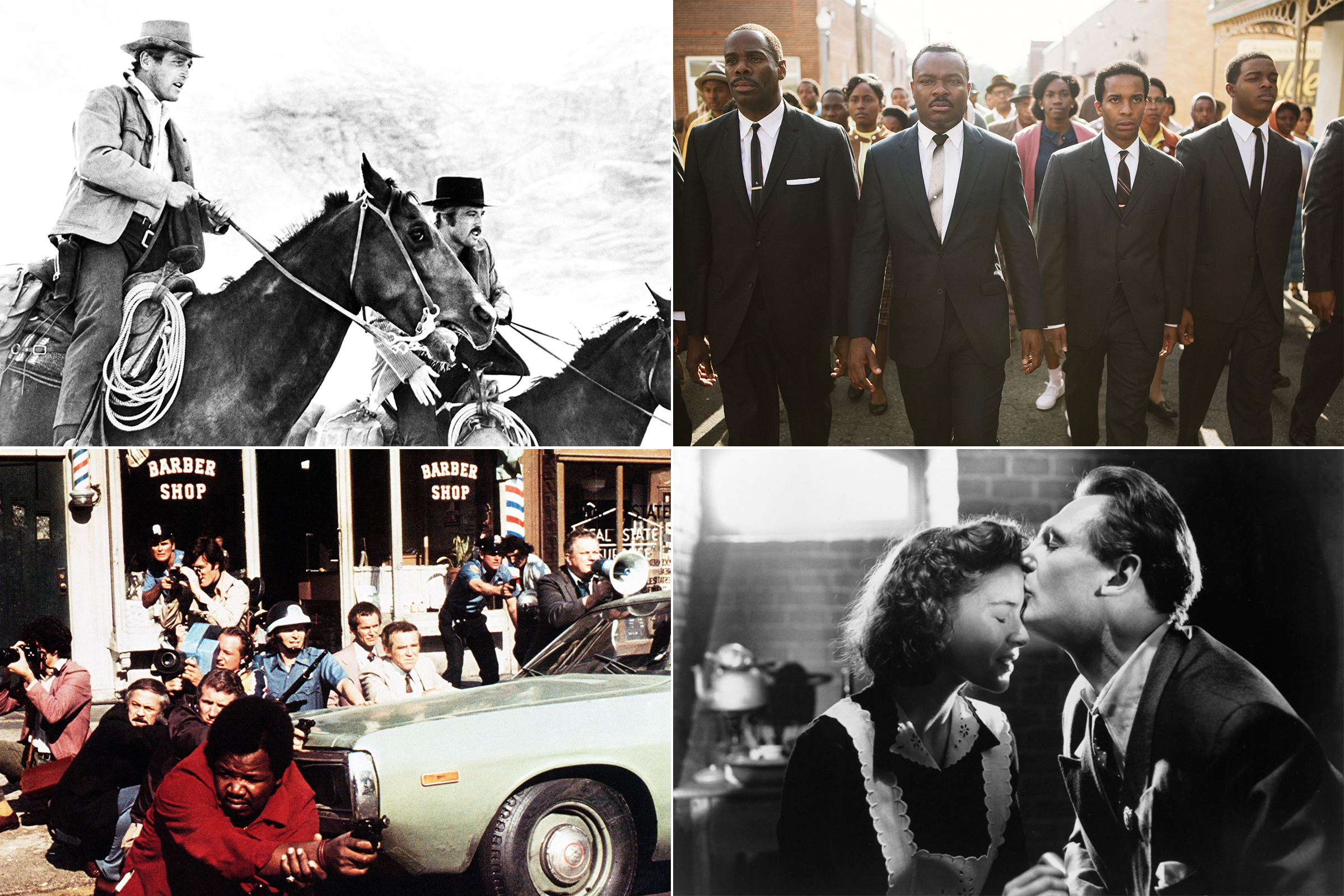

10. Selma (2014)

On March 7, 1965, as voting-rights demonstrators attempted to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., during a march to the state capital in Montgomery, they were met by heavily armed police. The day would—known as “Bloody Sunday,” after 17 marchers were hospitalized and 50 treated for lesser injuries—would become a key moment in the fight against racist voter suppression in the U.S., as televised images of the attacks on the marchers stunned the country. But the protesters (led by Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Hosea Williams and other civil rights leaders) did not give up.

These events are the backdrop for the Ava DuVernay-directed film Selma, which, with its re-creation of the months leading up to the marches, illustrates the complexities of social justice movements and their leaders. For Joseph P. Reidy, Emeritus Professor of History at Howard University, the film’s strength lies in both depicting the debates between leaders like King and John Lewis, and the stories of unsung local heroes “immortalized in contemporary newsreels,” which fueled public outrage and forced President Lyndon B. Johnson to condemn the violence inflicted on the marchers. “Beautifully crafted and impeccably acted,” Reidy says, “Selma offers a memorable tribute to the ordinary people whose extraordinary courage helped to reinforce a basic right of American democracy: the vote.” — Suyin Haynes

9. The French Connection (1971)

The complex drug trafficking scheme known as the French Connection was cooked up by Corsican gangsters in the 1930s: poppy seeds were shipped from Turkey and Lebanon to Marseille, a major French seaport, where they were processed into heroin, before being shipped out to U.S. By the 1960s, up to 44 tons were being moved in the U.S. yearly, prompting then-President Richard Nixon to dramatically crack down on drugs—and providing plenty of fodder for Robin Moore’s 1969 nonfiction book about some of the NYPD’s busts during the time, The French Connection. Two years later, director William Friedkin’s Oscar-winning film of the same name debuted, with a slightly fictionalized twist on the thrilling real-life drug seizures.

While Friedkin took some liberties with the film, including its iconic car chase, he was committed to keeping the story fairly realistic. To aid with this, he brought on Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso, the NYPD detectives who provided the inspiration for the film’s protagonists, Detective “Popeye” Doyle (played by Gene Hackman) and his partner Buddy “Cloudy” Russo (played by Roy Scheider). Egan and Grosso served as technical advisers on set for the entirety of production, as well as both acting in small cameos in the film. “The French Connection conveys the seediness of New York in the late ’60s and early 1970s,” says historian Amity Shlaes. “For those of us who love N.Y., the film was, until this year, a marker that showed how far the city had come after the 1970s lows. Now the film proffers hope: the city came back from decline before. The rough fraud cop played by Gene Hackman reminds us of something else: questionable policing is nothing new.” — Cady Lang

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

8. Schindler’s List (1993)

Filmmaker Steven Spielberg wanted the cast of his adaptation of Thomas Keneally’s 1982 historical novel to keep something in mind: “We’re not making a film, we’re making a document,” as he put it. Up until that point, there had been documentaries and European films about the Holocaust, but not a modern Hollywood blockbuster.

Liam Neeson stars as the real businessman Oskar Schindler, credited with saving more than 1,000 Jewish people by putting them to work in his munitions factory in Brünnlitz, in what’s now the Czech Republic. In reality, there was more than one list, written not by Schindler, but by a Plaszów camp orderly named Marcel Goldberg, that had the names of those cleared to be transported to Schindler’s factory—but that departure from fact did not mar the movie’s impact. The film was hailed not only by critics—it won the Academy Award for Best Picture—but also by Holocaust survivors, who found its depiction of what they went through and the brutality of the Nazi regime so realistic that it inspired many to share their own memories, thus enabling historians to preserve their stories for future generations. Though World War II ended nearly 80 years ago, the film’s lesson is a timeless one. “It is about the actions of someone who refused to go along with the evil,” says historian Julian Zelizer. “That’s a basic message, but one that resonates loudly in our day and age.” — Olivia B. Waxman

7. The Sound of Music (1965)

Julie Andrews running through the Austrian hills as Maria in the 1965 filmThe Sound of Music is perhaps one of the most well-known opening scenes in cinema history. Based on the memoir of the real Maria, the movie tells the story of a free-spirited nun sent to become a governess for seven musical children, just before the start of World War II. As in the film, Maria married Georg von Trapp (who was 25 years her senior in reality) and the family toured Europe in 1937 as the von Trapp family choir. The following year, they fled Austria, which had been annexed by the Nazis, and made their way to New York, where they held their first American concert in December 1938.

The Sound of Music debuted on Broadway in 1959 and the hit film was released six years later, largely remaining faithful to the true story, although the real Georg was said not to be as cold-hearted as his film double, and Maria was said to sometimes have a bit of a temper, contrary to Julie Andrews’ ever-cheery depiction. “In addition to providing a showcase for the meteoric talents of a young Julie Andrews, The Sound of Music also gives an excellent example of the slow creep of authoritarianism and bigotry,” says Danielle Bainbridge, assistant professor of theater and performance studies at Northwestern and host of the PBS Digital Studios series The Origin of Everything. “The insidious but steady integration of Nazi symbolism and ideology throughout the film, interspersed with upbeat musical numbers about rainstorms and young love, reveals dictatorships for what they truly are.” — Suyin Haynes

6. 12 Years a Slave (2013)

Black British director Steve McQueen’s triple Academy Award-winning 12 Years a Slave, starring Chiwetel Ejiofor and Lupita Nyong’o, is “a raw, horrifying and essential document,” declared TIME’s film critic. Ejiofor stars as Solomon Northup, a free African-American man who was living in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., when he was lured away and kidnapped in 1841 and sold into slavery in Louisiana. The film was based on Northup’s own 1853 memoir Twelve Years a Slave, which documented his treatment on the plantation and his eventual freedom and reunion with his family, as well as on input from historians and researchers.

“12 Years a Slave meets the high bar for historical accuracy as well as artistic excellence,” says Manisha Sinha, Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut, who recommends the film to her students as a source for their work. “It is for the most part extremely faithful to the original narrative of Solomon Northup, which I had taught in my class for years before the movie came out. I think he would approve.” — Suyin Haynes

Read more: 13 True Stories That Would Make Oscar-Worthy Movies

5. GoodFellas (1990)

“As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster,” declares Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill, protagonist of Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas, the 1990 classic crime film charting the rise and fall of a mafioso and his network in Italian-American Brooklyn. Viewers of the film, however, are left with plenty of reasons why a life in the mob might not be quite so desirable.

Billed as “the fastest, sharpest 2 1/2-hr. ride in recent film history,” by TIME’s film critic on its release, Goodfellas was based on the 1985 Wiseguy: Life in a Mafia Family by crime reporter Nicholas Pileggi, who also co-wrote the screenplay for the film. Pileggi’s book detailed the life of the real Henry Hill and his associates Thomas DeSimone and James “Jimmy” Burke. Their characters inspired those played by Joe Pesci and Robert deNiro in the movie, which featured the real 1978 Lufthansa heist at JFK Airport, thought to have been planned by Burke. “Goodfellas demythologizes organized crime, giving an audience primed by Coppola, Brando and Pacino a look at a world that was messy, bitter and unromantic,” says Jason Herbert, creator of Historians at the Movies and a PhD candidate at the University of Minnesota. “Plus, that garlic shot.”— Suyin Haynes

4. Spotlight (2015)

Starring Mark Ruffalo, Rachel McAdams and Michael Keaton as members of a real team of investigative journalists at the Boston Globe,Spotlight shows the efforts of reporters to uncover the history of systematic sexual abuse within the Archdiocese of Boston. The film is largely faithful to true events and based on real people; in January 2002, the Boston Globe Spotlight investigations team published their first story in a series of articles exposing the cover up of the abuse by Roman Catholic priests. Marty Baron, the current editor of the Washington Post, was the editor of the Globe at the time the film takes place, and is portrayed by Liev Schreiber in the film. “What is especially striking about the film is how well the director and writers effectively conveyed the real-life story of this group of courageous journalists—while carefully and delicately unveiling the personal lives of the victims of abuse,” says Keisha N. Blain, associate professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh. “By centering these difficult stories, in a moving, respectful and honest way, I think Spotlight is one of the best movies ever produced.” — Suyin Haynes

3. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

Paul Newman and Robert Redford stole hearts and set a new standard for the buddy film when they portrayed notorious real-life outlaws Robert “Butch Cassidy” LeRoy Parker and Harry “The Sundance Kid” Longabaugh in 1969’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. While the film begins with the disclaimer that “most of which follows is true,” in reality, the film takes plenty of creative liberties in the service of creating a rollicking, if not quite historically accurate, Western. Even the central relationship was really more of a casual working partnership than the best friendship portrayed in the film, according to Cassidy’s sister Lula Parker Betenson, and the film’s famous ending is still the subject of historical debate: did the two men die in Bolivia or, as Cassidy’s sister and great-nephew contend, did Cassidy escape?

Those questions, however, don’t detract from the movie’s impact—or that of the character of Etta Place, played by Katharine Ross, says Stephanie Coontz, emeritus faculty of history and family studies at The Evergreen State College. “I loved that the guys were so charmingly incompetent and self-deprecating in some areas, without being feckless buffoons. It was the first time I’d seen men willing to admit a woman into their adventures and allow her to be a real friend to one of them without any rivalry between them,” Coontz recalls of seeing the movie when it came out. “I reacted to the movie less as a history student, which I was at the time, than as a product of my own time—a young woman who was fed up with the gender stereotypes I’ve been brought up with.” — Cady Lang

2. All the President’s Men (1976)

A younger generation might know Bob Woodward for his exhaustive chronicles of the Trump Administration in his books Fear: Trump in the White House and Rage. But nearly half a century earlier, he was uncovering the secrets of another president: Richard Nixon. In 1972, he and Washington Post colleague Carl Bernstein began to investigate a break-in at the Democratic National Convention. After exhaustive research, they found that the break-in was part of a massive campaign of political espionage and sabotage on behalf of Nixon and against his opponents; the Watergate scandal soon brought about the downfall of Nixon’s presidency. The journalists and editor Ben Bradlee, says Barbara A. Perry, Gerald L. Baliles Professor and Presidential Studies director at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, are “genuine American heroes.”

Just four years after the break-in, Alan J. Pakula’s film was released, with Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman playing Woodward and Bernstein, respectively, in their dogged hunt for the truth. Pakula and screenwriter William Goldman finessed their journalistic pursuit into a nerve-wracking detective story with shadowy garage basement face-offs. Unlike Woodward and Bernstein’s book of the same name, the film focuses less on the actual details of Watergate, instead homing in on the personalities and procedures behind one of the biggest investigations of the 20th century, and important real-life supporting characters like Washington Post’spublisher Katharine Graham are left out. Its picture of the impact of the investigation, however, is very real. The film nabbed eight Oscar nominations; 20 years later, longtime Post writer Ken Ringle called it “the best film ever made about the craft of journalism.” — Andrew R. Chow and Cady Lang

1. Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Al Pacino has played many criminal masterminds over the course of his career, but John Wojtowicz isn’t one of them. On a scorching 1972 summer day, the Vietnam War veteran made a clumsy attempt to rob a Brooklyn bank, only to be penned in with hostages for a 14-hour standoff. Sidney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon depicts the agonizing time spent inside the bank, during which Wojtowicz agonized over his actions and unexpectedly bonded with some of his captives. Among our pool of 10 historians and 10 TIME staffers, everyone who had seen the film ranked it either “great” or “fantastic”—and, points out historian Annette Gordon-Reed, Pacino’s “explosive performance” also created a bit of history, in the form of the 1970s catchphrase “Attica! Attica!”

After the film’s release, Wojtowicz complained in a letter written from prison that the film was only “30% true,” although he also called Pacino’s depiction of himself “flawless.” However, some reporters have cast skepticism on Wojtowicz’s version of events, saying that his stated motive—to pay for a gender-reassignment surgery for his lover Liz Eden—was a cover for a mafia plot. Whether or not the movie was accurate, Wojtowicz is right about one thing: Pacino is undeniably fantastic, imbuing the character with pathos and pent-up frantic energy. The film would make Wojtowicz a folk hero to many—and actually did help fund Eden’s real-life surgery. — Andrew R. Chow

Correction, Nov. 20.

The original version of this story misstated Solomon Northup’s last name in three instances. It is Northup, not Northrup.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com