As many Americans prepare to toast their country’s past on the Fourth of July, there’s no escaping that not every facet of that history has been worth celebrating. In fact, for a great number, this very moment may fall into that latter category, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to rock the nation and a growing number of people confront the inescapable facts of past and present racism. June polling revealed that Americans are unhappier now than they have been in decades, and a majority believe the U.S. is heading in the wrong direction.

It is hardly consolation to be reminded that this is not the first low point in American history. But a look back at that past does reveal that, at the very least, even the worst moments contain lessons that can still apply today. And if we listen to those lessons, perhaps a better future will be possible. With that in mind, TIME asked 21 historians to weigh in with their picks for “worst moments” that hold a lesson—and what they think those experiences can teach us.

Here, they explain their choices:

March 16, 1968: The My Lai massacre

On March 16, 1968, U.S. Army soldiers in Charlie Company killed as many as 567 South Vietnamese civilians, including women and children, in what became known as the My Lai Massacre. When the public learned about the massacre in November 1969, with harrowing photographs of dead villagers on major American television networks and in newsweeklies including TIME, it created a firestorm of controversy. Ultimately, however, the perpetrators were never held accountable. The platoon commander Lieutenant William Calley Jr. was initially given a life sentence but, at the order of President Nixon, was put under house arrest instead. He was released three and a half years later. Twenty-six soldiers were charged in military courts but none were convicted. The massacre and its aftermath were in part a reflection of a racist belief that shaped American policy in Vietnam—that, as William Westmoreland, the commanding general in Vietnam, infamously said, “life is cheap in the Orient.” With the COVID-19 pandemic having brought with it a spike in hate crimes against Asians and Asian Americans, My Lai offers a tragic cautionary tale about what can happen if a nation’s leaders choose to look the other way when racism trumps decency.

Mark Philip Bradley is a professor of history at the University of Chicago, and author of The World Reimagined: Americans and Human Rights in the Twentieth Century

Read more about My Lai, on TIME.com

Aug. 28, 1955: Emmett Till’s Murder

Periodically an event so offends our conscience that people have no choice but to take action. The murder of Emmett Till in 1955 was such a moment. Sending a message by taking a Black life was sadly common in Jim Crow America, but when Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, decided to display his lifeless body to be photographed in an open casket for the world to see, it was the catalyst that set the civil rights movement in motion. So many participants cited that Jet magazine photo as motivation: the Greensboro Four who sat to demand service in a North Carolina Woolworth, the young activists of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee who risked their lives to ride for freedom, and Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech on the anniversary of Emmett’s death. Years later, when I met Mamie, she stressed the importance of carrying the burden of history and the weight of memory, no matter how painful or difficult. As another Black man lost to senseless violence activates our collective moral outrage, that burden remains as we strive to reach the full promise of America.

Lonnie G. Bunch III is secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

Read more about Emmett Till, on TIME.com

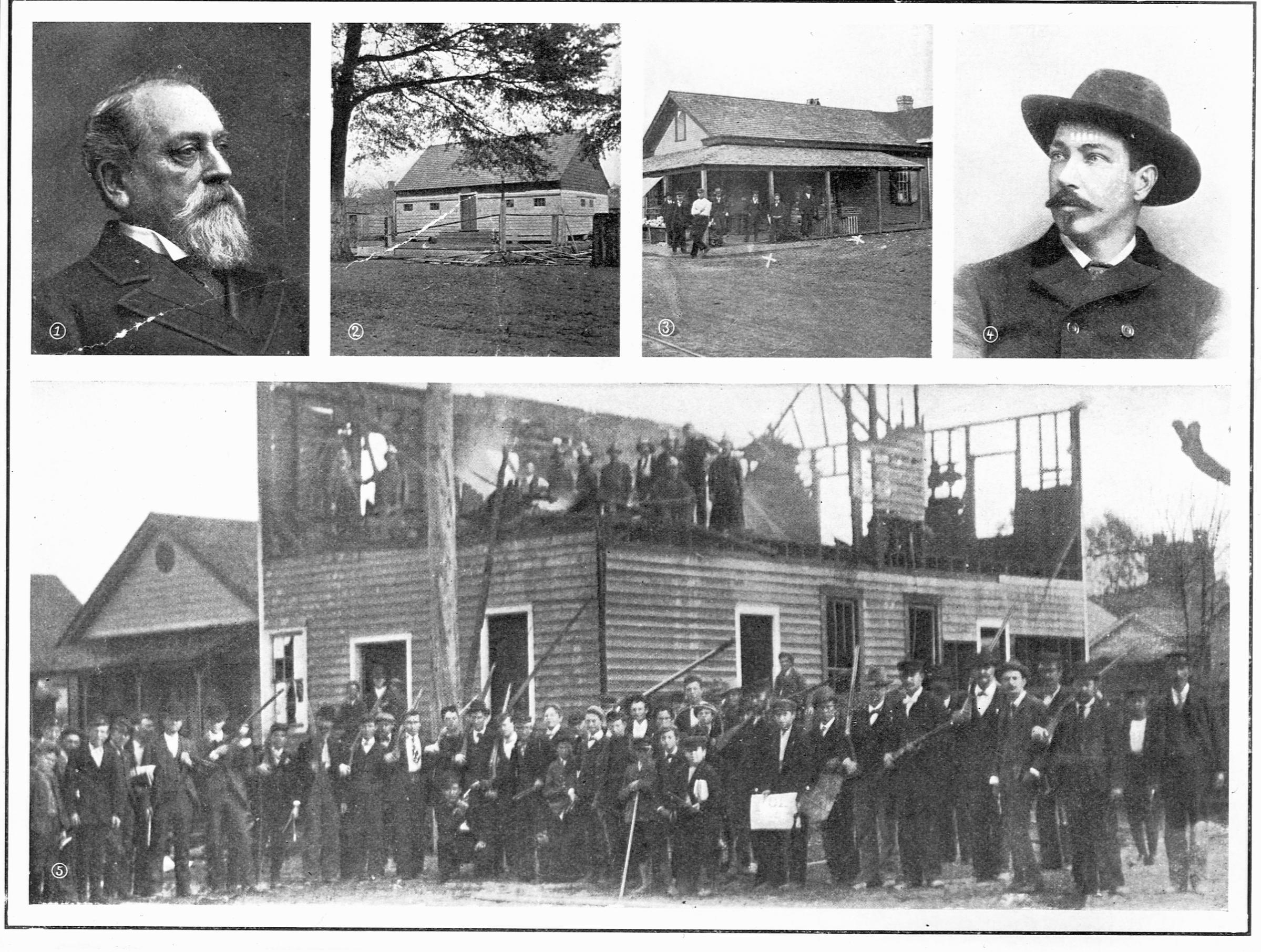

Nov. 10, 1898: The Wilmington Coup

In 1898, Wilmington, N.C., saw the only instance in U.S. history in which a legitimate government was overthrown by a white-supremacist coup. As David Zucchino details in Wilmington’s Lie, the city had a sizeable Black middle class and a multiracial government—but it was not free from the resentment of nearby white supremacists, who stockpiled weapons and promoted false reports of Black violence in the lead-up to the 1898 municipal election. Newspapers stroked white citizens’ fears and, despite numerous warnings, the federal government left Blacks in Wilmington to defend themselves. On Election Day, the white supremacists retook the government by force, made all Black politicians resign and declared a White Declaration of Independence. A riot ensued when Black men attempted to defend themselves; over 2,000 Black citizens were driven out of the city and 60 were killed. When the dust settled, the city’s Black population had dropped from 56% to 18%.

Recently, Black Americans have been outraged by the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. These Black Americans, like those in Wilmington, were citizens of a country where white-supremacist groups openly carry military-style weapons, and where forms of voter disenfranchisement exist in almost all 50 states. One thing I think we can learn from that moment is that we need white Americans to be just as outraged as Black Americans are. My students, who are predominantly African American, want to learn from this history — but at the end of the day, they can’t do it alone.

Alysha Butler is a history teacher at McKinley Technological High School in Washington, D.C., and the Gilder Lehrman Institute’s 2019 National History Teacher of the Year.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

1779: Smallpox in the American West

At the same time that the American Revolution was raging in the East, a smallpox pandemic occurred in the West that affected the course of American history.

Breaking out in Mexico City in 1779, it reached New Mexico and then spread along the networks by which horses had dispersed northward, devastating thriving and wealthy Native American tribes as it traveled along the Columbia River to the northwest coast and across Canada to the shores of the Hudson Bay.

The death tolls were staggering. This massive outbreak occurred in a region that was not yet “American,” but American history has always been shaped by events beyond the borders of the U.S. This event is a reminder that, even today, power and prosperity cannot guarantee immunity to disaster, and the heartland of America cannot escape the impact of developments thousands of miles away.

Colin G. Calloway is a professor of history and Native American studies at Dartmouth College, and author of The Indian World of George Washington: The First President, the First Americans, and the Birth of the Nation.

Read more about the history of smallpox, on TIME.com

March 3, 1873: The Comstock Act

Anthony Comstock was a dry-goods salesman from Connecticut who made combating sex in print his life’s work. He tirelessly lobbied until Congress in 1873 passed “an Act for the Suppression of Trade in and Circulation of Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use.” The most common such “literature,” however, was not pornography but advertisements for contraception. As the 19th century progressed, women—especially native-born, white, middle-class women—had decided to limit their fertility. In 1800, the average Protestant white women had seven or eight children; by 1900, she had 3.5. Comstock and other elite men were aghast, mainly at the idea that immigrants might out-populate white Protestants. The Comstock Act made information about birth control almost impossible to find.

The first real blow against the law came in Comstock’s home state. In Griswold v. Connecticut, the Supreme Court ruled that married couples had a “right to privacy that included the right to make decisions about childbearing and contraception free of government intervention.” The case provided precedent for Roe v. Wade, which was decided in 1973, a full century after passage of the Comstock Act. But during the intervening decades, women never stopped seeking to control when and under what circumstances they bore children—the most high-stakes decision of their lives. With the exception of the World War II period, the birth rate continued to decline among all groups. The fight over “Comstockery” made it clear that controlling fertility is a cause for which women will never stop fighting.

Rachel Devlin is an associate professor of history at Rutgers, and author of A Girl Stands at the Door: The Generation of Young Women Who Desegregated America’s Schools

Read more about the history of contraception, on TIME.com

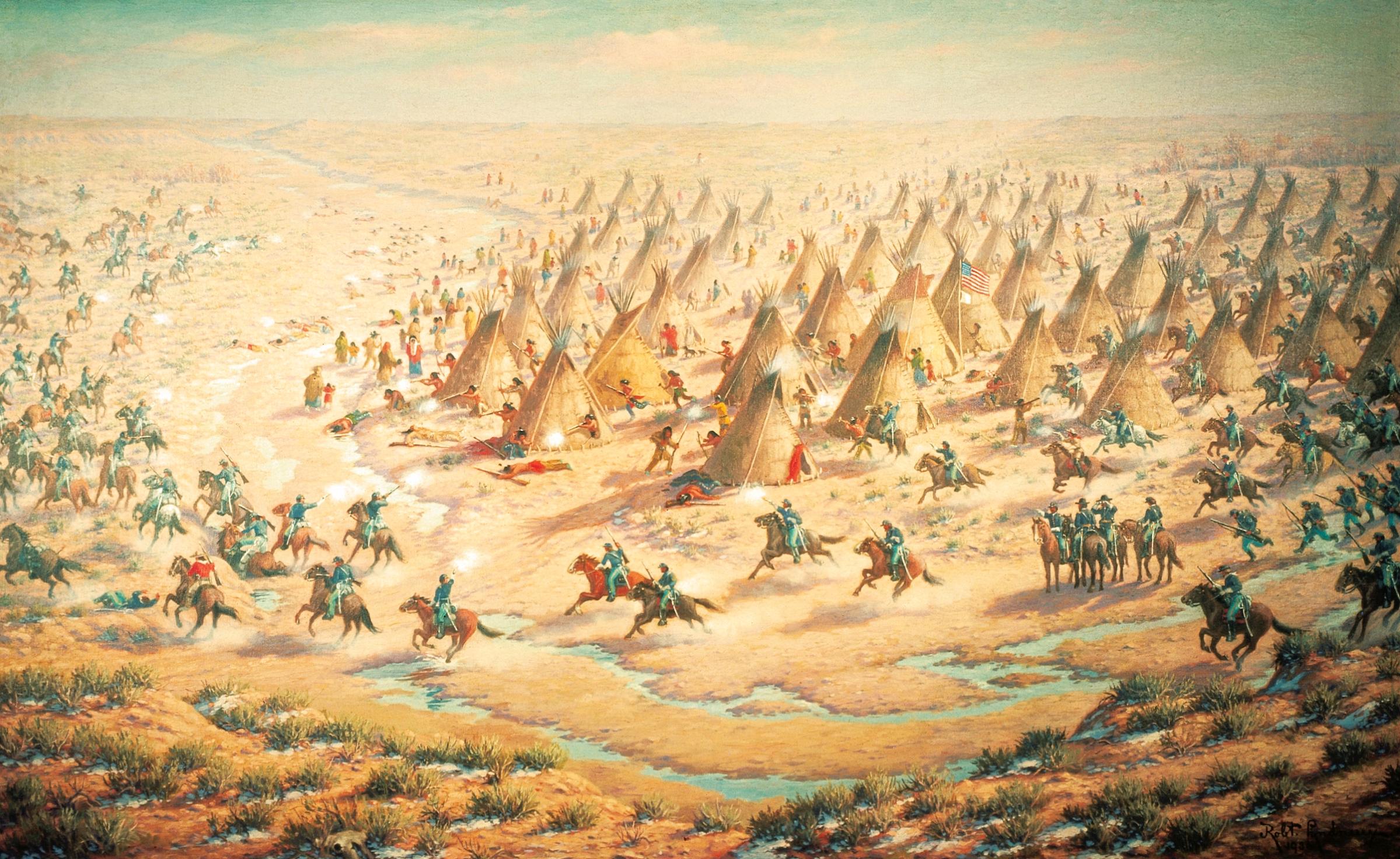

Nov. 29, 1864: The Sand Creek Massacre

On Nov. 29, 1864, a regiment of Colorado volunteer cavalrymen attacked an encampment of Cheyenne and Arapahos at Sand Creek, 180 miles southeast of Denver, killing about 200 people, mostly women and children. John Chivington, the pistol-packing minister who led the assault, described it as a glorious Union victory against “red rebels” who had sided with the Confederacy. But rumors of atrocities soon surfaced and led to congressional inquiries that cast the raid as a shameful slaughter of pacified Indians. Captain Silas Soule testified that troops shot, scalped and mutilated noncombatants. Two months later he was murdered in Denver. For years, Colorado memorialized the massacre as a battle and honored the soldiers as heroes. Tribal and white scholars, activists and descendants finally overturned that narrative in the 1990s. The lesson of Sand Creek is that life matters only when truth matters. The tragedy also reminds us of the courage of history’s whistleblowers and of our responsibility to carry on their work.

Vincent DiGirolamo is an assistant professor of history at Baruch College, CUNY, and the author of Crying the News: A History of America’s Newsboys.

Read more about the Sand Creek Massacre, on TIME.com

Jan. 28, 1969: The Santa Barbara Oil Spill

On Jan. 28, 1969, a Union Oil rig off Santa Barbara, Calif., suffered a blowout. Three million barrels of crude eventually blanketed 35 miles of coastline. An estimated 3,500 sea birds and countless marine animals, smothered by sticky goo, perished; images of their suffering seared the nation. Among the reporters and politicians who anxiously surveyed the carnage was President Richard Nixon, who translated what he’d seen into bipartisan policies including the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. In his 1970 State of the Union address, he acknowledged that the “question of the ’70s” was whether Americans could “make our peace with nature and begin to make reparations for the damage we have done to our air, to our land, and to our water.” He could see that if we didn’t make that peace, we’d have to live with the ugly consequences. Fifty years later, at a moment when a different Republican president seeks to roll back environmental protections, including those regulating offshore oil drilling, Nixon’s exhortation is more urgent than ever.

Darren Dochuk is a professor of history at the University of Notre Dame, and author of Anointed With Oil: How Christianity and Crude Made Modern America

Read TIME’s original coverage of the oil spill, in the TIME Vault

1969: Attacks on the Black Panther Party’s breakfast program

In 1969, the Black Panther Party’s Free Breakfast for Children Program fed tens of thousands of hungry kids in cities across the U.S. But, fearing the Panthers’ growing popularity, the FBI and local police tried to stamp the program out. In Baltimore, police raided the breakfast with guns drawn. In Chicago, police broke into the church that hosted the breakfast at night and smashed and urinated on the food. In Harlem, the police started rumors that the food was poisoned.

The FBI won the battle in some places because parents became afraid to send their kids to the breakfast. In other places, the tactic backfired as the community claimed the Panthers as their own. In future years, the Panthers renamed and expanded their community-based “survival programs” and, ironically, the USDA used the Breakfast Program as a model for a federal school breakfast program.

The Black Panther Party was explicitly militant, but it also had a visionary program of mutual aid. The FBI did not want people to understand that nuance, but we can only reckon with our history if we do. Looking at today’s movement for Black Lives, it’s equally important not to get lost in rhetoric, and to look instead at what activists are actually doing in their communities.

Nan Enstad is a professor of community and environmental sociology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and author of Cigarettes, Inc.: An Intimate History of Corporate Imperialism

Read more about the Black Panther Party, on TIME.com

June 19, 1865: Juneteenth’s promise denied

Juneteenth reflects freedom delayed and denied. The holiday is still celebrated as the day on which freedom came to enslaved Texans, by order of a proclamation from Union Major General Gordon Granger. But that moment, even while full of joy, was also a low point—a reminder of how incomplete that progress was. The newly freed Texans wouldn’t have been able to act as free people without Union troops’ enforcement protections. Nor did the proclamation offer citizenship, land or restitution for generations of toil. Instead, it offered a vision of freedom in which freedpeople still worked for, lived under and remained subject to white people. Black Americans suffered state and extralegal violence, coercion and exploitation, but they celebrated their day of jubilee as a claim on full freedom. Juneteenth is a quintessentially American holiday that evokes the struggle to realize the democratic ideals enshrined in the Constitution. The holiday reminds us how far we have come but also how much further we still have to go in making those ideals a reality for all Americans.

Shennette M. Garrett-Scott is an associate professor of history and African American studies at the University of Mississippi, and author of Banking on Freedom: Black Women in U.S. Finance Before the New Deal

Read more about Juneteenth, on TIME.com

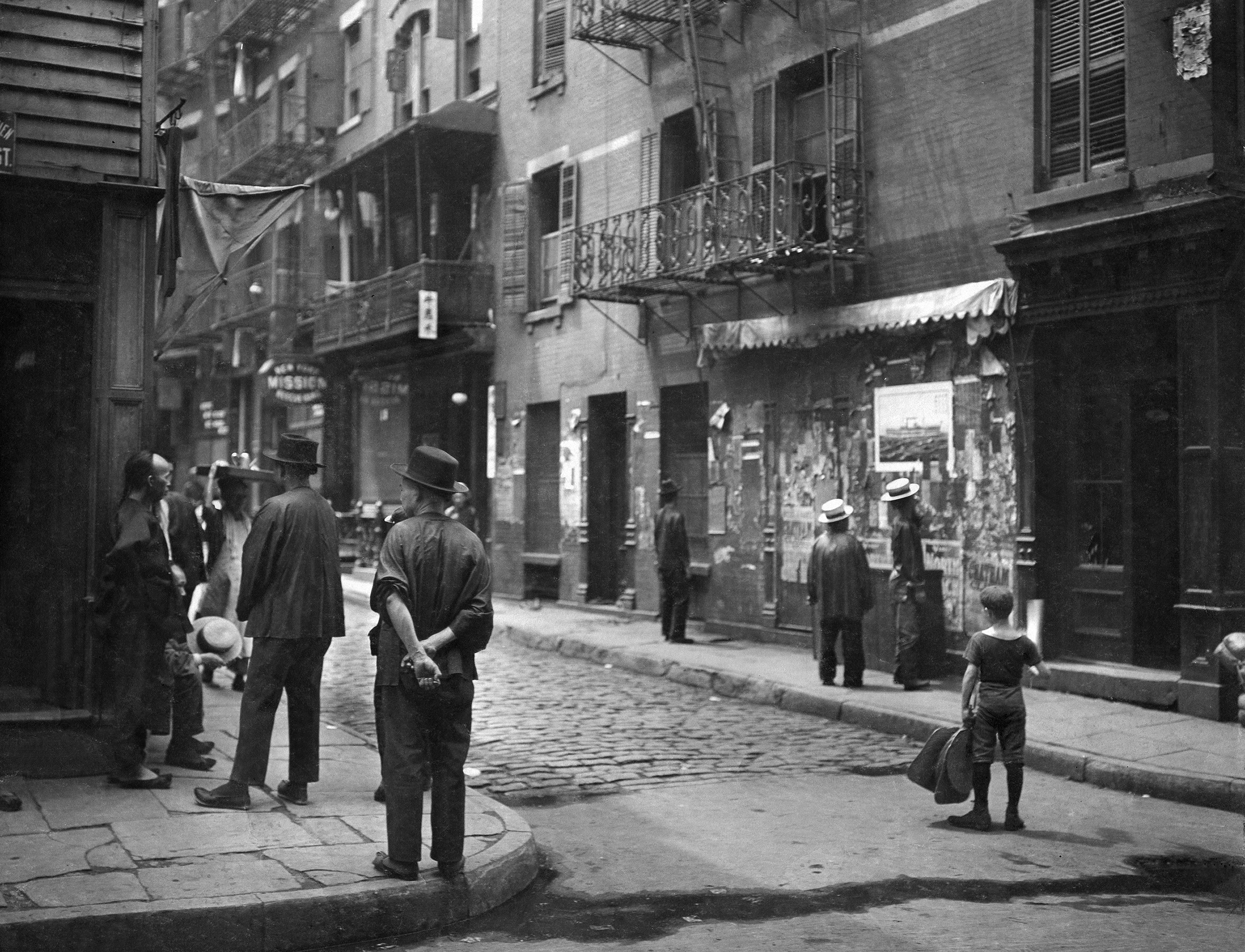

1956-65: The Chinese Confession Program

In 1882, the U.S. made Chinese people its first targets of enforced immigration restriction. As a result, most who immigrated during the period of “Chinese exclusion,” including my grandfather, did so through a complex system of faked documentation. When FDR repealed those the laws in 1943 he called them “a historic mistake,” but most Chinese Americans continued living in the shadow of their false identities, vulnerable to discovery and deportation. These historic problems came to a head in 1956, when the INS and FBI enacted the Chinese Confession Program, offering Chinese Americans citizenship in exchange for admitting they’d lied—and informing on others. The playwright David Henry Hwang has described the investigations, when raids for evidence of immigration fraud shut down San Francisco’s Chinatown, as “government terrorism.”

Only in the years after, however, can we see that the Confession Program was a turning point. Though Chinese Americans still experienced discrimination, they were not treated as “enemy aliens” or rounded up for deportation. The federal government had decided to accept this particular racial minority as legitimate U.S. citizens, and once-severe levels of legal discrimination diminished. This kind of treatment has not been extended to all groups—but the history shows that it is possible.

Madeline Y. Hsu is a professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin, and author of The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority

Read more about the history of violence against Asian Americans, on TIME.com

1662: Virginia’s Act XII

In December of 1662, the men who comprised Virginia’s General Assembly decided to resolve what they saw as a growing problem in the colony. Englishmen were having children with African-descended women, both free and enslaved. Some English fathers enslaved those children, but others treated their mixed-race children like free persons. While their decisions to free their children were consistent with English law, free mixed-race children blurred the racial divide forming in Virginia by the 1660s. In the eyes of the General Assembly, this inconsistency could not stand.

To fix the problem, they implemented Act XII, which declared that “Negro women’s children [were] to serve according to the condition of the[ir] mother[s]”— in direct contrast with paternal descent laws that prevailed in England. This law made enslavement a heritable condition and was instrumental in the formation of a racially divided society in which African descent signified bondage. It also financially incentivized acts of sexual violence against enslaved women.

The racial divisions of the world that we live in today can feel natural and inflexible. This law, however, stands as incontrovertible evidence that a racially divided society wasn’t natural at all, that it had to be made, and that it needed to be shored up year after year by laws and violence. These English men had to create new tools to build the white supremacist society they envisioned. We too can create new tools with which to change it.

Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers is an associate professor of history at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South

Read more about slavery in Virginia, on TIME.com

1911 and 1991: The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire and the Hamlet fire

The 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire was one of the worst U.S. industrial disasters, but we should consider it alongside another workplace catastrophe. On Sept. 3, 1991, a fire at the Imperial Foods chicken-processing plant in Hamlet, N.C., killed 25 workers and injured 56 who were trapped behind intentionally locked fire doors—an eerie echo of the conditions that led to 146 deaths in New York City in 1911. Most victims of the Hamlet Fire were women and many were African American. Most were single mothers, leaving over 50 children orphaned.

Though the Triangle Shirtwaist incident was followed by a wave of labor protection laws, as Bryant Simon explains in The Hamlet Fire, by 1991 national deregulation, anti-unionization, lax enforcement of safety standards and systemic racism created the conditions for another devastating event. Today, when the most precarious labor continues to fall disproportionately on women of color, and when the government has pushed a host of deregulation measures that have weakened protections for workers, it is vital to re-prioritize the regulations that protect workers’ pay, safety and rights to organize. Only then will we be able to live up to the words of one Hamlet Fire survivor: “putting money before life will never happen again.”

Katherine M. Marino is an assistant professor of history at UCLA, and author of Feminism for the Americas: The Making of an International Human Rights Movement

Read more about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, on TIME.com

1933-38: The New Deal’s exclusion of farmworkers

As America’s farmworkers suffered hunger, sickness and dislocation during the Great Depression, FDR’s New Deal legislation did little to improve their welfare—in fact, in many ways it left them worse off than they were before. At the time, Southern Democrats with an interest in preserving Jim Crow dominated Congress. Meanwhile, many farmworkers were people of color. Consequently, unlike most urban industrial workers, farmworkers were omitted from the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, the National Labor Relations Act and Social Security Act of 1935 and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. And due to complicated state residency laws, migrant farmworkers, even as American citizens, were excluded from public aid. This situation condemned them to a life in America without a place to enact their rights.

This is still the case today. Despite their contributions as “essential workers” in our food-supply chain, people who work on farms continue to experience the enduring consequences of the federal government’s refusal to afford them real security through extended labor and social protections. The impact of the New Deal on farmworkers is a reminder that policy decisions are often advanced in ways we don’t recognize as inherently exclusionary, and that such policies’ impacts can last far longer than the moment for which the laws were created.

Verónica Martínez-Matsuda is an associate professor of labor relations, law and history at Cornell University’s ILR School, and author of Migrant Citizenship: Race, Rights, and Reform in the U.S. Farm Labor Camp Program

Read more about the history of farmworker rights, on TIME.com

1930s: Repatriation of Mexicans

As unemployment rose to record levels during the Great Depression, Mexican migrants and Mexican Americans were simultaneously blamed for taking jobs from U.S. citizens and, paradoxically, for living off public welfare. In response, immigration officials started deportation campaigns to rid the country of unauthorized migrants, while those who could not be deported because they were legal residents or citizens were pressured to leave “voluntarily.” With the support of the Mexican government, county officials in the United States often sponsored trains to return ethnic Mexicans to the border. The number of repatriated Mexicans is hard to know but estimates range from least 350,000 to as high as 2 million, out of which 60% are believed to have been American citizens—most of them children. However, only a few years after the final episode of repatriation in 1939-40, U.S. officials were desperate to bring Mexican workers back to replace American citizens who had gone to fight in World War II. The repatriation campaigns show us that the problems for which migrants are often blamed are not solved by their deportation. This moment is a reminder of the importance of not seeing those who live among us as “others” who can be welcomed or shunned based only on the need for their work.

Ana Raquel Minian is an associate professor of history at Stanford University, and author of Undocumented Lives: The Untold Story of Mexican Migration

Read more about the repatriation program, on TIME.com

May 24, 1924: The Johnson-Reed Act

On May 24, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Johnson-Reed Act, which established the harshest immigration restrictions in U.S. history. The law banned Asians, who were already subject to exclusion laws, from naturalization entirely, and established immigration quotas that radically reduced the numbers of permitted Southern and Eastern European migrants, who were deemed less “white” than other Europeans. The Johnson-Reed Act used immigration restriction as a tool of racial engineering. It is no surprise that the Ku Klux Klan supported the law, and Adolf Hitler found inspiration in it.

Following WWII, policies that inspired the Nazi regime did not reflect well on the United States. Congress passed cosmetic reforms in immigration policy in 1952, and in 1965 followed that with the law that is seen as the Civil Rights Act of immigration—but even that law brought new quotas and maintained grounds for exclusion. And current immigration policy has been defined by exclusions, walls, deportations, removals and detentions. This story has not ended. We need to reckon with how much of U.S. history has been defined by whiteness—and we have an urgent responsibility to define our values going forward. Do we want to return to those roots, or to care for each other in all the fullness of our differences?

A. Naomi Paik is an associate professor of Asian-American studies at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and author of Bans, Walls, Raids, Sanctuary: Understanding U.S. Immigration for the Twenty-First Century

Read TIME’s original coverage of the law, in the TIME Vault

May 18, 1896: Plessy v. Ferguson

In some ways, the Supreme Court’s 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld Louisiana’s statute mandating segregation in all public facilities, was the nail in the coffin. Since 1876, the courts and Congress had steadily eroded the Reconstruction Amendments’ promises to African-Americans: suffrage, equal protection of the law and due process before the law. But the Plessy opinion and its embrace of “separate but equal” let African Americans know once and for all that, despite the Constitution’s guarantees, their fundamental rights would not be protected.

Plessy v. Ferguson was not overturned until 1954, and only because of decades of dedicated work by civil rights attorneys and organizers. From Plessy, we know that the letter of the law, and even the Constitution, is insufficient and potentially even meaningless if it is not applied fairly or consistently. We also know that some laws, like the Louisiana segregation statute, contravene basic principles of the Constitution. Democracy requires that we do more than rely upon or simply follow the law; we have to insist upon virtuous laws, and passionately reject oppressive ones. History teaches us that if we sit idly by, even the most noble laws can be distorted by bigotry—and bigoted laws, left unchecked, can lead to immense suffering.

Imani Perry is a professor of African American studies at Princeton University, and author of May We Forever Stand: A History of the Black National Anthem

Read more about Plessy v. Ferguson, on TIME.com

1865: Restitution denied

In October of 1865, Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, Commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, undertook a journey to coastal South Carolina. The prewar plantation owners who had fled their property there early in the Civil War now demanded the restoration of their estates, and President Andrew Johnson was eager to oblige the barely remorseful traitors. But a major obstacle stood in that path: Gen. William T. Sherman had issued possessory titles to these lands to formerly enslaved people. Howard was there to get the freed people to accept labor contracts with their former owners instead of the land they’d been promised. In the decades that followed, tensions between the white planters and the Black laborers in the Lowcountry alternately flared and fizzled. In an ironic twist, freed people and their descendants did end up gaining title to some of that land later in the 19th century—as numerous plantation families gave up trying to maintain their estates without enslaved laborers—only to see the land pass into the hands of developers in the 20th century. Besides betraying his vow to make treason odious, Johnson had frustrated the freed people’s aspirations for land, and in doing so destroyed an early chance to address the economic and social inequality that originated in slavery. When America breaks its promises, the repercussions can last for centuries.

Joseph P. Reidy is professor of history emeritus at Howard University, and author of Illusions of Emancipation: The Pursuit of Freedom and Equality in the Twilight of Slavery

Read more about reparations, here on TIME.com

Aug. 19, 1953: Operation Ajax

The British long exercised colonial power in Iran through the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. In 1951, as British colonies began to wrest their freedom from the empire, Iranian prime minister Mohammed Mossadegh nationalized the oil company in a similar act of anticolonial defiance. In response, the British turned to the U.S., appealing to American fears of Soviet influence. So, in August 1953, in “Operation Ajax,” two intelligence agencies, MI6 and the CIA, overthrew the popular, democratically elected Persian government. The Shah became a U.S.-backed autocrat, who Iranians saw as a puppet using American arms and policing techniques to loot Persia’s oil wealth. This was the colonial regime the revolution in 1979 overthrew. In 1953, the U.S. colluded in inventing a covert mode of pursuing colonialism in an ostensibly post-colonial world. More such actions followed in the region and elsewhere, stoking backlash against a hidden American hand continuing where the British and French had left off. The interventions were covert to evade the check of both American and global public opinion. When we tout America’s democratic traditions, we must understand that their effective functioning depends on our watchfulness and active curiosity.

Priya Satia is a professor of history at Stanford University, and author of Empire of Guns: The Violent Making of the Industrial Revolution

Read TIME’s cover story on Mohammed Mossadegh, here in the TIME Vault

April 27, 1721: Smallpox in Boston

On April 27, 1721, His Majesty’s Ship Seahorse sailed into Boston Harbor leading a convoy of ships from the West Indies. Unknown to Bostonians, the cargo included smallpox; several sailors had caught the dreaded disease in Barbados. When the infected seamen went ashore to carouse in Boston’s pubs they started a chain of transmission that within nine months killed eight percent of the city’s residents — the equivalent of 56,000 Bostonians today. To combat the disease, some townspeople put their faith in a procedure then new to Western science: inoculation. To spur a mild form of the disease and confer immunity, a physician would insert pus from smallpox blisters into an incision in a healthy person’s arm. Eighteenth-century anti-vaxxers responded with outrage; one even threw a grenade through the window of inoculation’s greatest proponent. That early smallpox inoculation technique was a key step toward lifesaving vaccines, but in Boston, public-health measures proved more effective in slowing the disease, a lesson that resonates today. Vaccines eventually eradicated the disease—but in the short term, quarantines, self-isolation and school closings saved more lives than inoculation.

Erik R. Seeman is a professor of history at the University at Buffalo, and author of Speaking with the Dead in Early America.

Read more about the history of epidemiology, on TIME.com

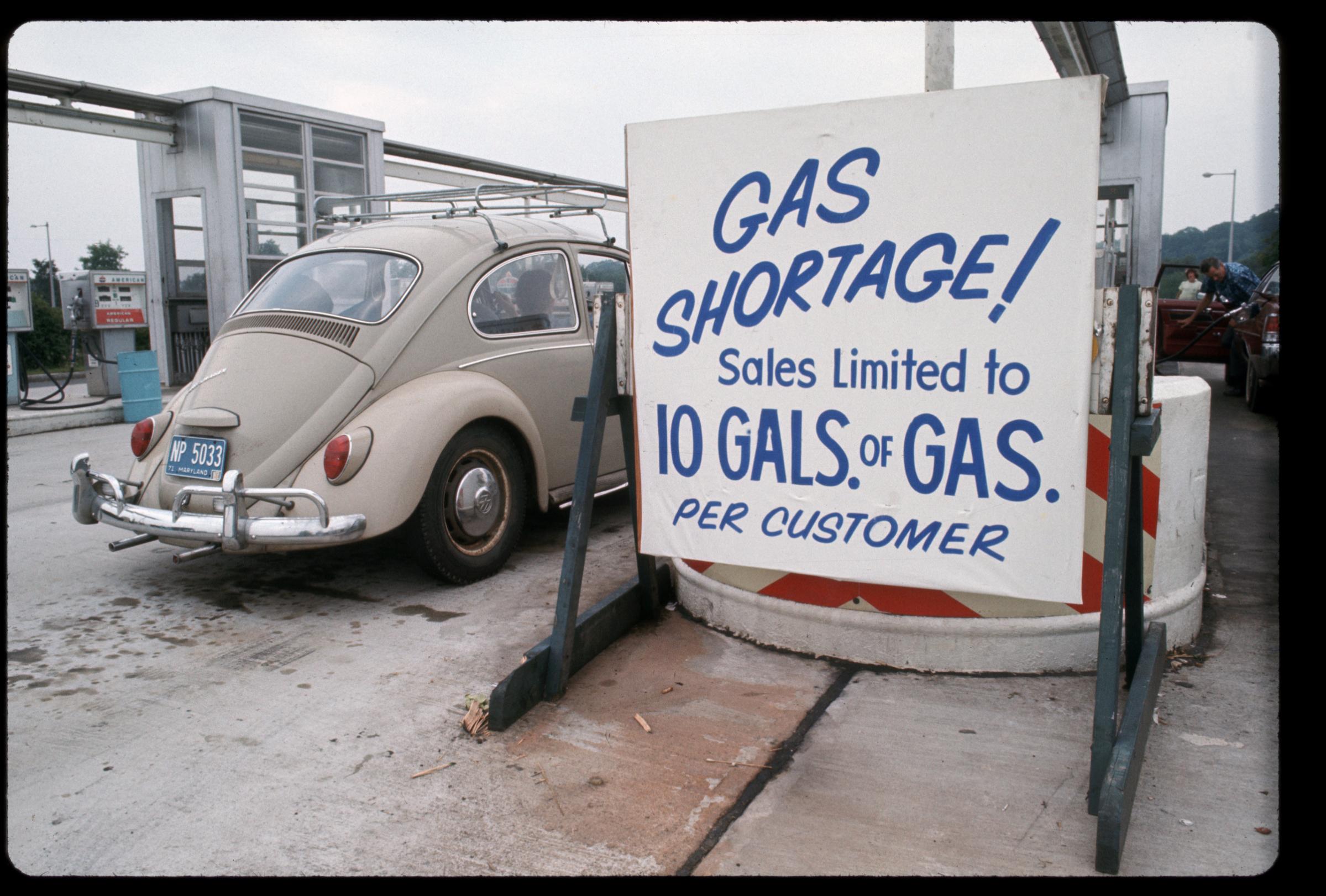

Oct. 20, 1973: The Arab oil embargo

The Energy Crisis of the 1970s left Americans with an ambiguous legacy. At the time of the 1973-74 Arab oil embargo, the crisis was understood as a symptom of the West’s decline following decolonization, the end of the gold standard, the failure of the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal and more. By the time we marked the 40th anniversary of the embargo, Americans had repurposed the tale to celebrate capitalism’s triumph over both the Soviet Union and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries—but the long-term story may still turn out to be a sad one.

After the embargo, Americans expended more effort finding new sources of hydrocarbons (offshore, fracking) and defending existing sources in the Persian Gulf than rethinking our addiction to oil. Unfortunately, we were too successful: we found enough oil and gas to wreck our climate and created a financial incentive not to limit consumption until it’s perhaps too late. The self-defeating consequences of our response to the Energy Crisis suggest it’s dangerous to be obsessively focused on economic growth. Many people believe such growth is the only way to save liberal capitalism, but prioritizing it over everything else means putting our generation’s well-being over that of our grandchildren.

Anand Toprani is an associate professor of strategy at the U.S. Naval War College, and author of Oil and Great Powers: Britain and Germany, 1914-1945. The views he has expressed here are his own and not necessarily those of the U.S. Government.

Read TIME’s original coverage of the embargo, in the TIME Vault

1793: Yellow Fever in Philadelphia

In 1793, more than 10% of the U.S. capital city’s population died from a poorly understood viral infection. Philadelphia’s Yellow Fever epidemic disproportionately affected older and poorer people, and upended the city’s economy as wealthy people fled and the government scattered. It also intensified conflicts over immigration, racism and slavery, and turned the spotlight on medical experts as well as leaders of the city’s growing Black community, as both free and enslaved Black Philadelphians provided essential support to the sick and dying throughout the city. Legacies of that moment included new public health and sanitary infrastructure—including Philadelphia’s first waterworks—and the westward shift of the population away from the city’s densely packed neighborhoods and into new suburbs, as well as a rich set of medical and political reflections on the experience of the epidemic, including a defense of Black people’s critical role. What ought to arrest our attention about the epidemic, though, is that its impact sounds so familiar in the midst of COVID-19: epidemics expose longstanding patterns of discrimination and inequity, which both immediate and longer-term responses amplify rather than reduce.

Karin Wulf is a professor of history and director of the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture at William & Mary, and author of Not All Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia

Read more about the historical overlap between public health and discrimination, on TIME.com

A portion of this list appears in the July 6, 2020, issue of TIME

Correction, July 6

The original version of this article misstated the name of one of the contributors. She is Karin Wulf, not Karin Wolf.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com