These are independent reviews of the products mentioned, but TIME receives a commission when purchases are made through affiliate links at no additional cost to the purchaser.

When I think of my childhood, I think of all the trappings of the late 1980s and early ’90s—beatable video games, quick-melting Popsicles, dares and double-dares and double-dog-dares. But what was just as present as all these were the color-splashed covers of comic books, the thin periodicals trapped between plastic and cardboard, lined up in a box in my older brother’s room. A superhero Rolodex. He treated them like my mother treated her record collection. Sacred. Special. Celebrated like trophies, revered like jewels. Like ancient artifacts to be peered at and preserved.

Truthfully, I never had my own. And because of that—because they were always at a distance—I thought of them as something to be careful with. Something off-limits to me. My brother, Allen, made it clear that they weren’t to be touched. So, of course, like any good little brother, I disobeyed. I remember sneaking in and sliding an Amazing Spider-Man comic from its sleeve, then flipping through the pages of panels, far more interested in the pictures than the words. Spider-Man shooting intricate web patterns on walls and lampposts. Spider-Man swinging, soaring through the sky from building to building. Spider-Man. . . winning.

But as I got older, Allen, whom I’d catch gingerly turning the pages of his comics, started to talk to me about what he was reading, started to give his little brother some insight about the words on those pages, specifically as they pertained to Peter Parker. He explained that what made Peter different from all the other superheroes was that he was just a regular kid. This was a big deal to me but an even bigger deal to my older brother—who thought of himself as so regular that he was irregular.

Read More: Jason Reynolds: YA Books Make Us Feel Safe to Be Who We Really Are

Allen had challenges. He struggled in school due to a learning difference, and the resources to help back then weren’t nearly what they are now. A round kid with a heavy hand and a meek personality, he’d been teased and bullied most of his adolescent years. And because of the tormenting of his real-life villains, which sometimes played out physically, he found life was better lived inward. Safer in the shell. He was more than shy or introverted. He was afraid. Afraid of people. Of new things. New experiences. Afraid he’d make a mistake and be laughed at. So while Spider-Man, for me, meant heroic victory, meant shooting invisible webs at my mother and pretending to climb the walls, for Allen, Peter Parker meant possibility. He meant the underdog getting over. He meant vindication for the outsider.

Peter Parker, my brother explained, was the first superhero teenager who acted like a teenager. He was an orphan, raised by his uncle Ben and aunt May, which for us felt normal, not because we were orphans—we weren’t—but because it wasn’t uncommon for people in our family to be raised by extended members. Peter was awkward, a bit uncomfortable in his own skin. My brother (and I, later) also felt this way, begging our mother for name-brand, ill-fitting clothing, doing anything to fit in. Peter was also insecure in a way that caused him to feel inadequate, lonely. This, too, was my brother’s story. He struggled with believing that his life was one of worth, because so many people had told him otherwise.

Peter Parker was my brother, Allen. And Allen was Peter. And because of that familiarity, that representation, Allen could then become Spider-Man. He—a boy who actually loved insects, especially spiders (I have stories!)—could mask up, and use the super powers he’d been given due to the toxic bite life had delivered.

Read More: The Definitive Ranking of Every Single Spider-Man Movie

Spider-sense. Allen could intuit bad things, villains who meant him harm.

Wall climbing. He knew how to escape. Anything. Everything.

Web shooting. When Allen wasn’t running, he could connect things. He had an invisible tether, a personality that once he (reluctantly) let loose, would pull you in. Would stick.

And above all these super powers, Spider-Man also helped my brother—a struggling student—to read, which, to me, is the most important weapon of all.

I’ve spent my life believing the Amazing Spider-Man is in my corner, because he built up and fortified my personal superhero. Those pages brought power to my older brother’s life and showed him, showed us both, that a teenager could be more than a sidekick, and that a hero doesn’t have to be perfect. As a matter of fact, Peter Parker, the stumblebum from Queens, showed us that it’s how the imperfections are used that determines one’s heroism.

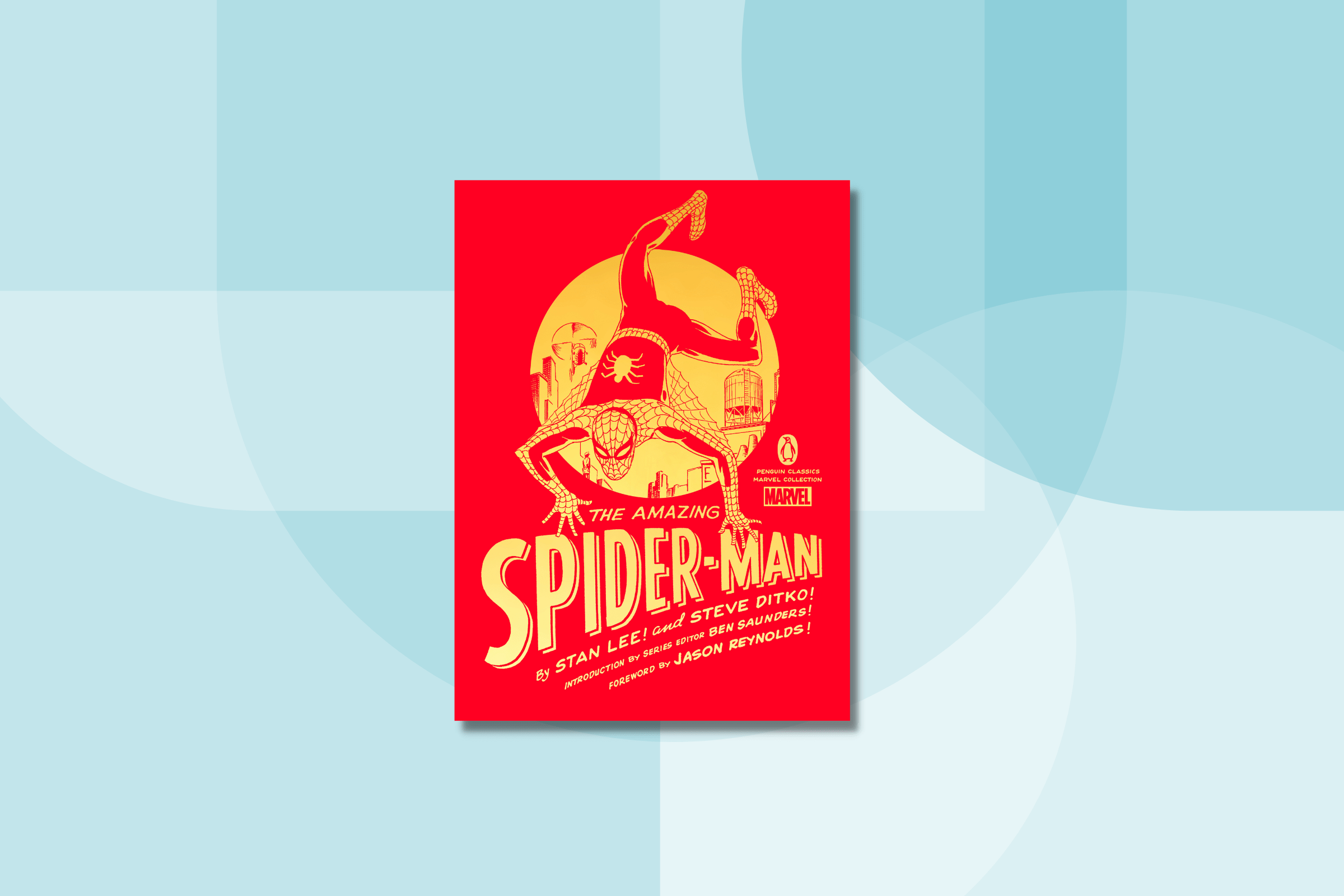

From THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, to be published on June 14, 2022 by Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Foreword copyright © 2022 by Jason Reynolds.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com