On a brisk Monday in Houston in early March, dozens of protesters gathered across the street from the giant Hilton hotel hosting CERAWeek, the energy industry’s hallmark annual conference. Their signs accused the corporate executives inside of betraying humanity in pursuit of financial return. STOP EXTRACTING OUR FUTURE, read one. PEOPLE OVER PROFIT, read another. Two days later, inside a standing-room-only hotel ballroom, Jennifer Granholm, the U.S. secretary of energy, offered a different message to the executives: the Biden Administration needs your help to tackle climate change. The scene encapsulated this moment in the fight to address global warming: some of the most ardent activists say that companies can’t be trusted; governments are saying they must play a role.

They already are. The U.S. Department of Energy has partnered with private companies to bolster the clean energy supply chain, expand electric-vehicle charging, and commercialize new green technologies, among a range of other initiatives. In total, the agency is gearing up to spend tens of billions of dollars on public-private partnerships to speed up the energy transition. “I’m here to extend a hand of partnership,” Granholm told the crowd. “We want you to power this country for the next 100 years with zero-carbon technologies.”

Across the Biden Administration, and around the world, government officials have increasingly focused their attention on the private sector—treating companies not just as entities to regulate but also as core partners. We “need to accelerate our transition” off fossil fuels, says Brian Deese, director of President Biden’s National Economic Council. “And that is a process that will only happen if the American private sector, including the incumbent energy producers in the United States, utilities and otherwise, are an inextricable part of that process—that’s defined our approach from the get go.”

Get a print of the Earth, Inc cover here

For some, the emergence of the private sector as a key collaborator in efforts to tackle climate change is an indication of the power of capitalism to tackle societal challenges; for others it’s a sign of capitalism’s corruption of public institutions. In the three decades since the climate crisis became part of the global agenda, scientists, activists, and politicians have largely assumed that government would need to dictate the terms of the transition. But around the world, legislative attempts to tackle climate change have repeatedly failed. Meanwhile, investors and corporate executives have become more aware of the threat climate change poses to their business and open to working to address its causes. Those developments have laid the foundation for a new approach to climate action: government and nonprofits partnering with the private sector to do more—a new structure that carries both enormous opportunity and enormous risk.

Read More: This Mining Executive Is Fighting Her Own Industry to Protect the Environment

Just 100 global companies were responsible for 71% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions over the past three decades, according to data from CDP, a nonprofit that tracks climate disclosure, and pushing the private sector to step up is already showing dividends. Last fall, more than 1,000 companies collectively worth some $23 trillion set emissions-reduction goals that line up with the Paris Agreement. “We are in the early stages of a sustainability revolution that has the magnitude and scale of the Industrial Revolution,” says Al Gore, the former U.S. Vice President who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work on climate change. “In every sector of the economy, companies are competing vigorously to eliminate unnecessary waste to become radically more energy efficient, and focus on the sharp reduction of their emissions.”

Despite that momentum, risks abound. Companies have an incentive to make big commitments, but they need a credible system to set the rules of the road and ensure that those pledges can be scrutinized. Even then, corporate progress is unlikely to add up to enough without clear policy that incentivizes good behavior and/or punishes bad behavior. “To catalyze business, we need governments to lead and set strong policies,” says Lisa Jackson, vice president of environment, policy and social initiatives at Apple and a former head of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “That’s just what the science says.”

Nor are companies built to address the array of social challenges—millions displaced, millions more with livelihoods destroyed, the escalating health ailments—that will arise from climate change and the transition needed to address it. “The private sector has been surprisingly aggressive on climate in the last 12 months,” says Michael Greenstone, former chief economist in Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers. “But that is a very misshapen approach: there’s no real substitute for a coherent climate policy.”

It’s increasingly hard to imagine how we find such a policy in time. In February, the IPCC, the U.N.’s climate science body, warned of a “rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a livable and sustainable future.” Emissions need to peak by 2025 in order to have a decent chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C. In a landmark report outlining the possible levers to cut global emissions, the IPCC found that private sector initiatives, if followed through, could make a “significant” contribution to that goal. The group assessed the impact of 10 private sector initiatives, and found they could result in a total of 26 gigatonnes in reduced or avoided emissions by 2030—equivalent to more than five years of U.S. carbon pollution.

How this partnership between government and industry plays out will shape not just the trajectory of emissions over the coming years and decades but also the future of democratic governance and how society will manage the now inevitable social disruption that will result from climate change.

To understand how we got here, it’s helpful to look back to a remarkable coincidence of history. Climate change entered public consciousness at the same time that, in the U.S., the zeitgeist turned against government’s playing a robust role in society. In 1988, when then NASA scientist James Hansen offered his now famous warning that the planet was already warming as a result of human activity, and TIME soon after named the “Endangered Earth” as “Planet of the Year,” American voters had spent eight years hearing President Ronald Reagan tell them that government lay at the root of society’s problems.

So it’s perhaps no wonder that in the decades that followed, government attempts to tackle a new problem, unprecedented in scope and scale, encountered roadblocks. That effort began in earnest in 1992 as heads of government from around the world gathered in Rio de Janeiro to inaugurate a new U.N. framework to address climate change. Every year since, with the pandemic-related exception of 2020, countries have met to hash out solutions to the problem. But, in the first two decades of talks, a comprehensive solution failed to break through. In the U.S., the lagging climate policy can in large part be attributed to the then pervasive free-market ideology, which dictated that businesses exist to make a profit. From the 1990s, and into the new century, fossil-fuel companies as well as heavy industry spent millions denying the existence of the problem and funding organizations that opposed climate rules. Other firms remained on the sidelines of an issue that seemed unrelated to their core business. The results in the political arena were clear. President Bill Clinton tried to pass an energy tax in Congress, but a concerted lobbying effort from manufacturers and the energy industry doomed the plan. George W. Bush publicly questioned the science of climate change and appointed executives from the oil and gas industry into senior positions in his Administration. Barack Obama pursued comprehensive climate legislation that would have capped companies’ emissions in 2009; the legislation failed to make it to the floor of the Senate after a prominent group of businesses condemned it.

But around that time, many business leaders began to feel pressure to do something on climate for the first time. Prioritizing environmental, social, and corporate governance concerns in investing, or ESG for short, had risen from a niche idea in the early 1990s to a mainstream approach to investment two decades later. At that point, a growing flow of reports from financial institutions warned of the economic consequences of inaction. And key voices in the business community—from Michael Bloomberg to Bill Gates—took the message on the road, telling CEOs to take climate change seriously. From 2012 to 2014, the value of investment in the U.S. earmarked for sustainable funds that took into account ESG issues close to doubled, to nearly $7 trillion, according to data from the U.S. SIF Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for sustainable investment strategies.

To foster this momentum, government leaders sought to bring business into the policymaking conversation. Their goal was to create what is often referred to as a virtuous cycle: if they could get commitments from the private sector on climate issues, they argued, it would, theoretically, push government to do more, which in turn would push companies to double down. In 2015, that approach was put into practice as a group of business leaders showed up in Paris to talk with government officials. The result: CEOs declared their commitment to reducing emissions, and the final text of the Paris Agreement created a formalized framework for involving private companies in the official U.N. process.

Just a year later, the U.S. elected Donald Trump as President and began to unravel the country’s environmental rules. Five months into office, he announced that he would take the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement. Within hours, 20 Fortune 500 companies declared that they were “still in” the global climate deal and would cut their emissions in hopes of keeping the U.S. on track. By the time Trump left office, more than 2,300 American companies had joined the coalition. For many pushing climate action, working with the private sector became the best path forward. “More and more power is distributed in societies,” Antonio Guterres, the U.N. Secretary-General, told me in 2019, explaining his extensive outreach to the business community on climate. “If you want to achieve results, you need to mobilize those that have an influence in the way decisions are made.”

The most important private-sector push came from the institutional investors at the center of the global economy, who control trillions of dollars in assets and are invested in every sector and essentially every publicly traded firm. When you own a little bit of everything, the scenarios portending climate-driven economic decline are terrifying. “We’re too big to just take all of our hundreds of billions, and try to find a nice safe place for that money,” Anne Simpson, then-director of board governance and sustainability at CalPERS, California’s $500 billion state pension fund, told me in 2019. “We’re exposed to these systemic risks, so we have to fix things.”

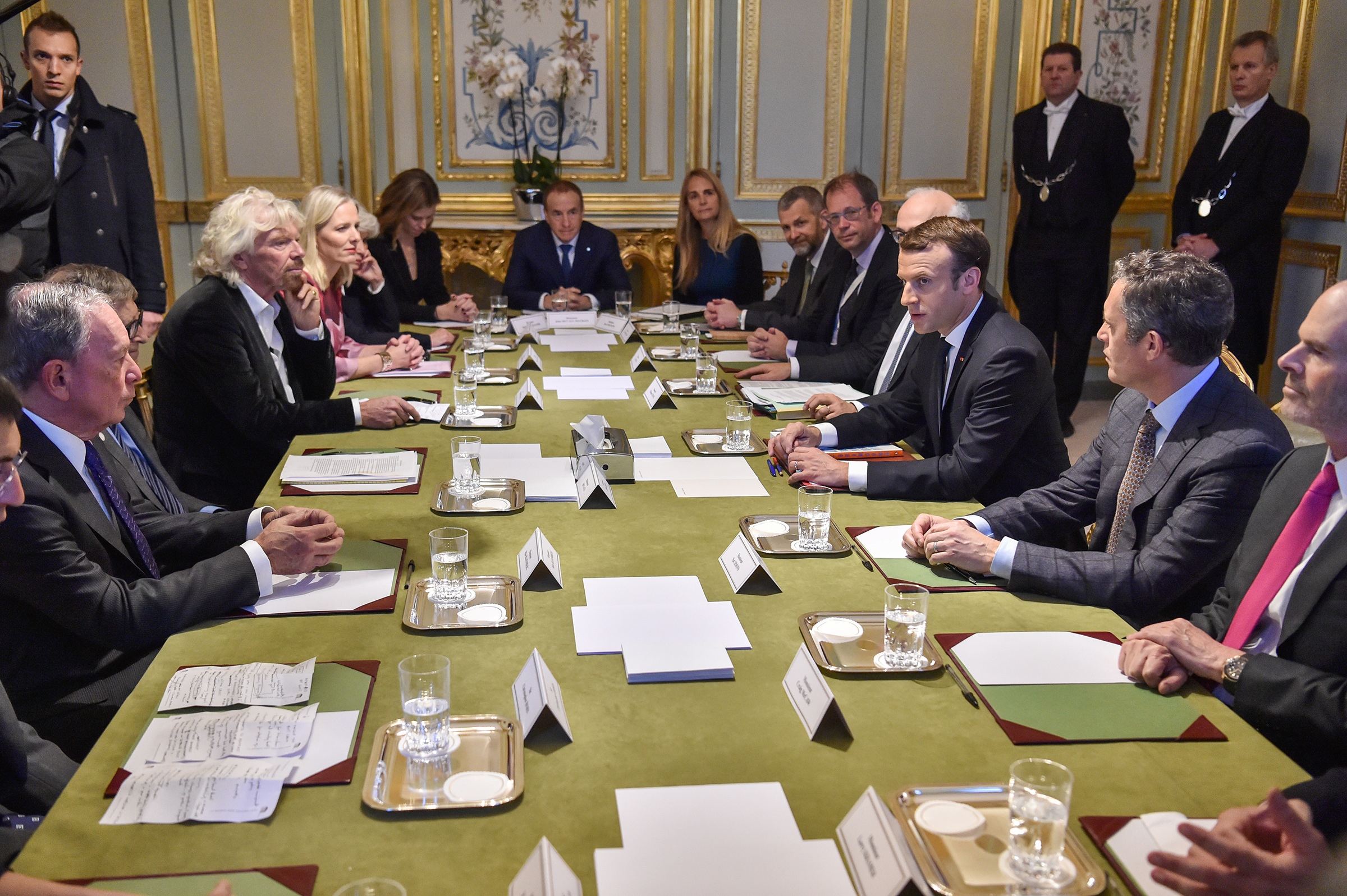

With the U.S. government on the sidelines, these investors joined together to send a signal. When French President Emmanuel Macron hosted a climate summit in Paris in December 2017, he brought together a group of investors controlling $68 trillion in assets to launch Climate Action 100+. In the beginning, this consortium used their status as high-profile investors to push emissions reductions in 100 publicly traded companies through one-on-one engagements with high-level executives.

“All of this made for a reorganization of the politics of climate,” says Laurence Tubiana, a key framer of the Paris Agreement who now heads the European Climate Foundation. “It has now crystallized into something new: a strong coalition between business, financial institutions, investors, and governments.”

All these threads came to a head last year in Glasgow at the U.N. climate conference. Walking around the Scottish Events Center last November, it would have been easy to forget that the conference was ostensibly for government officials. An attendee could easily spot, among the 40,000 attendees, high-profile business leaders mingling in the hallway. And by many accounts, the most significant news involved the private sector. Six major automakers joined with national governments to declare that they would produce 100% zero-emissions passenger vehicles no later than 2035. A group of financial institutions representing $130 trillion in assets committed to aligning its investments and operations with the Paris Agreement.

What sort of emissions reduction does this all add up to? The truth is no one really knows. An analysis of more than 300 member companies of the Science Based Targets initiative, a leading voluntary program for corporations to set emissions reduction targets in line with the Paris Agreement, found that, on average, each company succeeded in reducing their direct emissions annually by more than 6% between 2015 and 2019. But the global framework for emissions reduction centers on country-level commitments, and in its most recent report, the IPCC noted the ability to track corporate progress separate from national-level commitments remains “limited.”

The multilateral system for addressing climate change inaugurated in Rio, created by government for government, has evolved into something else. And, in the assessment of many activists, the result has left out concerns about justice in the transition. In Glasgow, activists and civil-society groups complained about being excluded from negotiating rooms while business leaders were ushered onstage. “It now looks more like a trade summit, rather than a climate convention,” says Asad Rehman, who organized for the COP26 Coalition, a climate-justice group. These activists worry about what the resulting government decisions look like when they’re made hand in hand with businesses. “The very people who created this crisis are now positioning themselves as the people who will solve it,” says Rehman. “The decisions being made seem very much to be locking us into a particular approach to solve the crisis—and, of course, that approach is not necessarily in the best interest of the people.”

Last December, just a few weeks after returning to the U.S. from Glasgow, I caught a flight from Chicago to Washington, D.C., on what United Airlines billed as the first flight operated with an engine running on only a lower-carbon alternative to jet fuel. As we approached Reagan Airport, Scott Kirby, the airline’s CEO, told me about the coalition—including companies like Deloitte, HP, and Microsoft—he has formed to help bring the fuel to market. “This is not just about United Airlines; this is about building a new industry,” Kirby told me. “To do that, we’ve got to have a lot of airlines participate, we’ve got to have partners participate… and we’ve got to have government participate.” Kirby had chosen Washington as the destination for this flight for a reason: to truly deploy the technology would require some help from the U.S. government.

The Biden Administration has been eager to serve as a partner, proposing a tax credit for sustainable aviation fuel and using the bully pulpit to tout United’s work—and aviation is just the tip of the iceberg. The administration has sought to partner on climate with companies across the country and across industries.

It almost goes without saying that Biden has been the most aggressive U.S. president yet on the climate issue. His administration has introduced or tightened more than 100 environmental regulations; worked with activists to address the inequalities worsened by climate change; and put climate at the center of “Build Back Better,” its signature $2 trillion spending package that failed to pass Congress last year. He has worked with activists to address the inequalities worsened by climate change. But engagement with the private sector offers a different avenue to push for emissions reduction, and, administration officials say, it has been a key part of his climate strategy. “That’s him availing every tool he’s got,” says Ali Zaidi, Biden’s Deputy National Climate Advisor, of Biden’s private sector engagement. “One of those superpowers that he has is the ability to meet people where they are and bring them along.”

That approach is also based in a sense of realism: the technologies we need to cut emissions over the next decade exist today and any reasonable consideration of how the world can cut carbon emissions means deploying those technologies as quickly as possible—largely by getting companies to adopt them. We need “to take the technology that DOE has spent so many years working on and actually get it in the hands of consumers,” says Jigar Shah, who runs the department’s Loan Program Office.

I met Shah, who previously ran a clean energy investment fund, in a small conference room in Houston where he had been taking meetings with a range of companies to convince them to do business with his agency—and more broadly the federal government. Shah has $40 billion at his disposal to invest in promising companies and projects. The idea, he says, is if business and government work together, they can move quickly to build a low-carbon economy by restoring the country’s ability to do big things. “We actually haven’t done these big things for 30 years,” he says. “America truly has sort of lost this general understanding of, like, how does an airport add a runway? How does a road get widened? Who makes the decision on upgrading our wastewater treatment plant?”

The business-oriented approach to climate change permeates the Biden Administration. Last September, I watched in the back of the room in Geneva as John Kerry, Biden’s Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, pitched the Administration’s approach to CEOs of some of the world’s biggest companies, presenting more than 30 slides detailing a new government program to catalyze production of clean technologies, in sectors ranging from air travel to steel manufacturing. Instead of government mandates, Kerry proposed that companies themselves take the lead by making deals to purchase clean technology. “Because we’re behind, we have got to find ways to step up,” he told the gathered CEOs.

Read More: Biden Wants an American Solar Industry. But It Could Come at an Emissions Cost

Kerry’s approach echoes the realism of the Biden Administration’s. The truth is that in 2022 Big Business has the power to influence—and halt—much of what the government does. “I’m convinced, unless the private sector buys into this, there won’t be a sufficient public-sector path created, because the private sector has the power to prevent that,” Kerry told me in September. “The private sector has enormous power. And our tax code reflects that in this country. And what we need is our environmental policy to reflect the reality.”

It makes sense then that from the outset the Biden Administration’s climate-spending plan has focused primarily on carrots rather than sticks. That is, it included a laundry list of rewards for companies doing positive things—namely tax credits for clean energy and subsidies for technologies like electric vehicles. Meanwhile, the two key policies that would have penalized businesses for their emissions—a fee for methane emissions and a tax when power companies failed to meet emissions-reductions targets—were abandoned after industry pushback. Despite those concessions, the most influential trade groups that lobby in Washington on behalf of big businesses still refused to back the overall legislation—because it required an increase in corporate taxes. It’s a reality that climate advocates readily decry as hypocrisy, and an indicator that business isn’t serious about climate change.

In the coming weeks, as negotiations for a revamped climate-spending bill accelerate, businesses will have another chance to show they are serious about climate policy. It brings to mind a key moment in a panel I moderated in April last year with Granholm, and a handful of top corporate executives’ work to reduce their companies’ emissions. “You are visionaries and you are leading, and there’s so many thousands of other businesses that can learn from your example, and there are a lot of members of Congress that could learn from your words. And it’s not to get political, but sometimes folks just need to hear,” she told them. “To the extent you can, we’d be really grateful because we feel like our hair is on fire.” They can still help, but the clock is ticking.

Even before Joe Biden took office, the American auto industry had begun to adopt the President-elect’s ambition of a rapid transition to electric vehicles. Within weeks of the election, GM dropped a lawsuit that sought to block more stringent fuel-economy standards. Two months later, it said it would go all electric by 2035. Meanwhile, Biden committed to a federal-government purchase of hundreds of thousands of electric vehicles. Since then, the U.S. auto industry has become an electric-vehicle arms race, with companies left and right announcing new capital expenditures to advance the national electric-vehicle fleet. GM says it will spend $35 billion in the effort over the next few years. Ford says it’s spending $50 billion.

“The biggest thing that’s happening here is there’s a realization, on the part of both labor and business now, that this is the future,” Joe Biden said as he stood with auto industry executives, union leaders and administration officials on the White House lawn last August.

Last year, I traveled to Ohio and Tennessee to see firsthand how the pressing questions about this transformation were playing out on the ground in the cities and towns that have relied on the auto industry for decades. In conversations with workers and local officials, I could sense excitement, but also consternation. Building an electric vehicle requires less labor than does its old-fashioned counterpart, and there’s no guarantee that new jobs created will be covered with a union. “There’s just going to be a lot less people building cars,” Dave Green, a GM assembly worker who previously led a local UAW branch in Ohio, told me at the time.

The green transition will also displace oil, gas, and coal workers. Entire cities in flood and fire zones will be dislocated. Diseases will spread more quickly. How will society manage such problems, accounting for a diverse array of interests, without a comprehensive, government-led approach to the transition? Not well, if past transitions are any indicator. Inequality soared during the Industrial Revolution, and the U.S. is still dealing with the economic fallout of globalization in the 2000s, when many blue collar jobs were outsourced.

To make up for the slow pace of government policy to guarantee an equitable transition, many activists have set their sights on influencing corporations directly. In 2019, for example, hundreds of Amazon employees walked out of work, insisting that the company do more to address climate change. Across a range of industries, corporate leaders now say that climate change is a top concern for recruits. Consumers, too, have begun to push companies to change, largely through the power of their dollars, by refusing to buy from companies with poor labor and environmental practices. “It’s not perfect,” says Michael Vandenbergh, a law professor at Vanderbilt University Law School who served as chief of staff at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under Clinton. But “it will buy us time until the public demands that government actually overcome some of the democracy deficits that we face.”

As challenging as it may be in these polarizing times, overcoming that democracy deficit is necessary, not just to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels but also to protect those most vulnerable to the effects of climate change and to the necessary changes ahead. It’s for that reason that the upswing in climate-activist movements—from the youth’s marching for a Green New Deal to the union members’ joining with climate activists to push for a just transition—matters beyond any policy platform. Climate change will reshape the lives of people everywhere. A truly just transition will require people to engage in the fight to fix it.

—With reporting by Nik Popli and Julia Zorthian.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com