More than three decades after the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the first World AIDS Day on Dec. 1, 1988, the world’s leading global health organization faces another public health crisis in COVID-19. On this World AIDS Day, those who raised awareness of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, find devastating similarities and haunting differences in America’s response to both crises.

In 1981, scientists recorded the first cases of a rare pneumonia, usually found among immunosuppressed patients, among a group of gay men in Los Angeles, and noticed more cases appearing among gay men in San Francisco and New York City, as well as cases of the rare cancer Kaposi sarcoma. In 1982, the CDC gave those cases a name, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and scientists confirmed the virus that causes it, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), in 1984. AIDS patient deaths in the U.S. steadily rose from 122 in 1981 to more than 50,000 at the peak of the AIDS epidemic in the U.S. in 1995. Since the beginning of the epidemic, about 75 million worldwide have become infected with HIV, nearly 38 million are living with it today—including roughly 1.2 million in the U.S.—and about 32 million people worldwide have died of AIDS-related illnesses, according to the United Nations.

From the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, comparisons have been drawn between it and the spread of AIDS. Many have pointed out the stark public response differences between the two outbreaks and how the lag in outcry over the deadliness of AIDS cost lives.

“The people who were suffering from HIV and AIDS, especially in the early days, were shunned,” says Henry Waxman, a former congressman from California who chaired a House subcommittee on Health and the Environment in the early days of the AIDS epidemic (and who is not related to the author of this TIME article). “When we found out about this disease, we didn’t even know its name because no name had been given to it, but it affected gay men primarily, was geometrically multiplying with people, [among] people who didn’t want to talk about it, because of the those who were involved, who suffered from it. and those people who are gay men faced a very different situation in the early ’80s than they do now… [The COVID-19] pandemic, as awful as it is, is a very different situation. We had trouble getting money to do anything to fight back against the AIDS epidemic, but we’ve had no problem at all getting money to fight back against COVID, which is, is a very good thing.”

Prominent figures involved in the response to the AIDS crisis in the U.S. in the 1980s and 1990s say that the delay in scientists identifying the virus that causes AIDS is a major factor in the difference between the responses to AIDS and the COVID-19 pandemic. Days after reporting that a ‘viral pneumonia’ was spreading in Wuhan, Chinese public health officials knew they were dealing with a novel coronavirus and the genome of the virus had been sequenced, while in contrast, it took years it took to identify HIV as the cause of AIDS.

“When HIV was first recorded, it was first recorded in the U.S., and largely among gay men and then injecting drug users, persons with hemophilia, heterosexual partners with people who had it, but the cause wasn’t really discovered for two years,” Jim Curran, who headed up the CDC’s task force on AIDS in the 1980s, explains. “So it would be a little like people dying of COVID without a virus being isolated, and so there was a lot of uncertainty and unknown about who had it or who didn’t have it. By the time the virus was discovered, the epidemic was already widespread throughout the world… Cases were doubling every five or six months. Initially, it was very difficult to get people’s attention.”

AIDS and COVID-19 spread in very different ways, and both public health crises required unique responses geared towards different populations: AIDS prevention measures focused on education around condom use, socializing safely and safe sex, compared to COVID-19 prevention involving education about social distancing and wearing masks.

“The major differences [between getting infected with HIV and COVID-19] are the modes of transmission and the duration of infection; HIV is transmitted through sexual contact, in blood, and mothers to newborns but on other hand it lasts forever and it’s inevitably fatal,” Curran says. “In the absence of therapy, when you’re infected, you’re infected for life. On the other hand, it’s not transmitted through the air like coronavirus, but coronavirus can be beat in three weeks for the most part, in most people, unless they die.”

Curran says the initial federal response to AIDS was hindered by “neglect,” but not any kind of White House attempts to interfere with the data that the CDC publishes. “If the CDC had important information, it was never modified.”

“Public health is always political, but shouldn’t be partisan during a pandemic,” says Curran. “It’s political because you have a new problem occurring, and you have to get all of the populations engaged in dealing with it.”

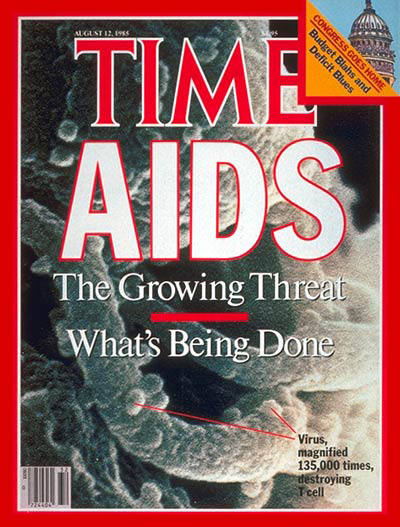

In contrast to 2020’s almost round-the-clock media coverage of COVID-19, it took a high-profile celebrity case to make the general population realize how widespread HIV/AIDS was becoming. The first major turning point in AIDS awareness came on July 25, 1985, when actor Rock Hudson, a friend of the Reagans, revealed he had AIDS, and died two months later. President Reagan began to take this public health crisis more seriously after learning of Hudson’s diagnosis, a former physician of Reagan told the New York Times in 1989. As TIME described the dramatic shift in mainstream public perception on HIV/AIDS in the Aug. 12, 1985 issue:

[I]t was the shocking news two weeks ago of Actor Rock Hudson’s illness that finally catapulted AIDS out of the closet, transforming it overnight from someone else’s problem, a “gay plague,” to a cause of international alarm. AIDS was suddenly a front-page disease, the lead item on the evening news and a frequent topic on TV talk shows. There seemed no end to the reports.

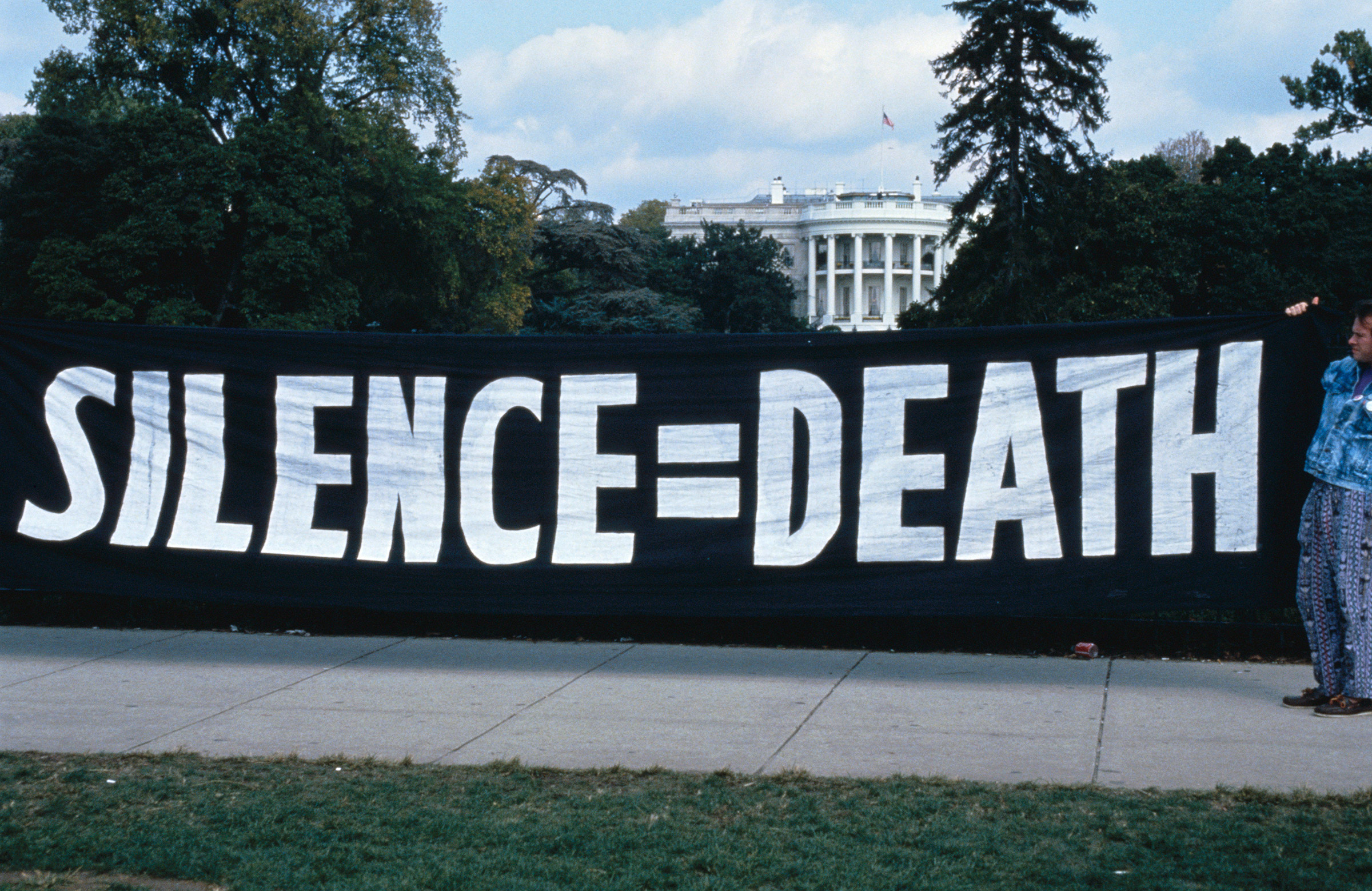

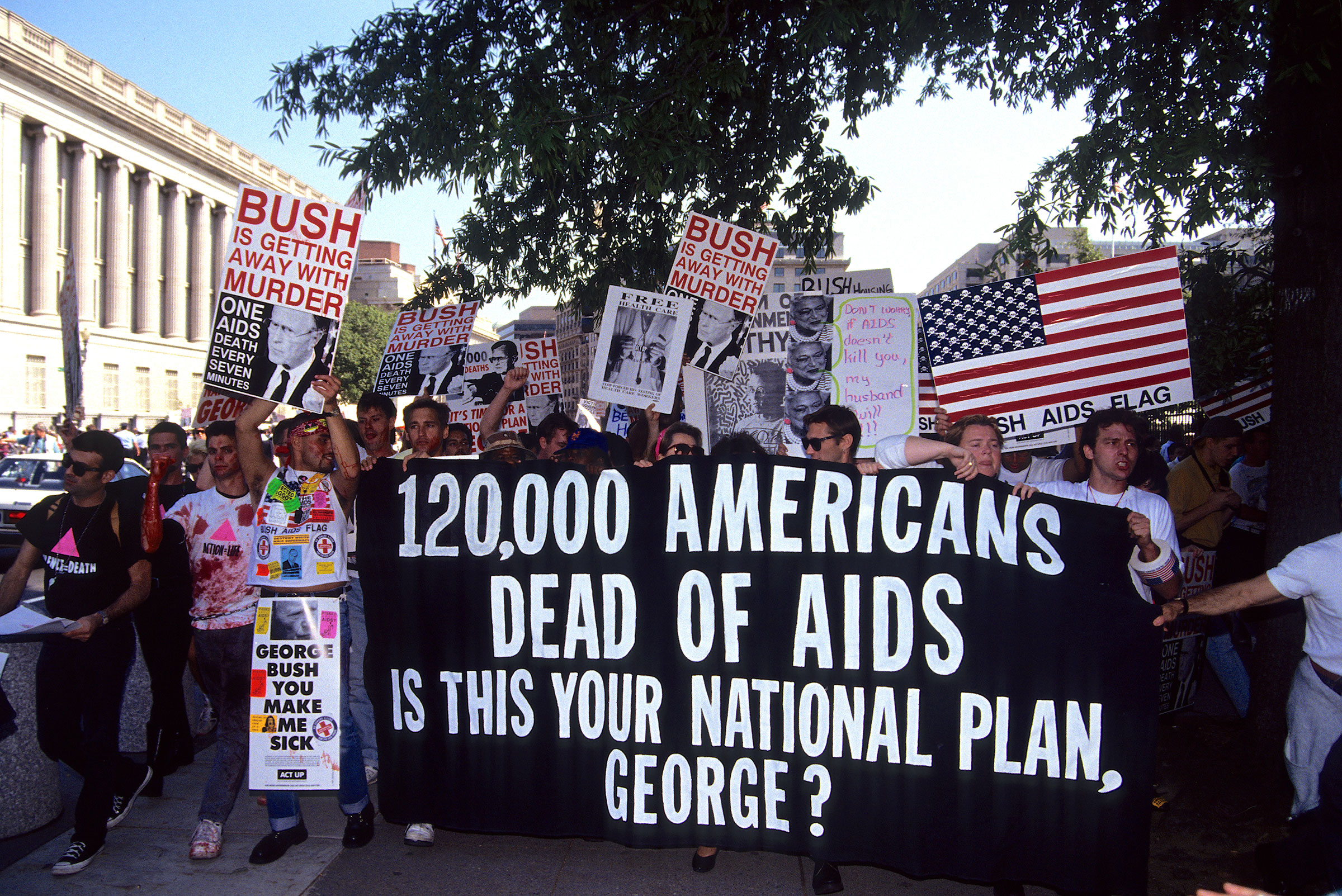

AIDS patients and advocates in groups like ACT UP also aimed to draw attention to the climbing death rate through bold actions, from spreading the ashes of AIDS victims over the White House lawn and organizing funeral processions carrying the bodies of AIDS victims.

And yet, it was a non-celebrity AIDS victim who spurred the landmark legislation of the peak of the AIDS crisis after nearly a decade of resistance to federal funding for AIDS research: The death of 18-year-old hemophiliac Ryan White on April 8, 1990, six years after making headlines in 1984 for contracting AIDS through a blood transfusion. Ronald Reagan, who didn’t publicly mention AIDS until 1985, four years into the crisis, eulogized Ryan White in the Washington Post. Then-Atlanta congressman John Lewis told the New York Times, “There is no way we can go around anymore saying this is an issue just affecting the gay community. In recent days, the life and death of Ryan White brought it home to many, many people.”

Four months after the teen’s death, President George H.W. Bush signed the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act, the largest federal HIV care and treatment program. The AIDS crisis also is one factor that led to landmark legislation the Americans with Disabilities Act signed by President George H.W. Bush a month prior in July 1990.

While there are many differences between the AIDS epidemic and the COVID pandemic, prominent figures in the public health response see a parallel between the lack of strong national leadership initially and resistance to proven public health solutions. Today, opponents of mask wearing, which helps prevent the spread of COVID-19, say they violate their personal freedom and don’t want governments to tell them what to do, while back then, there were a combination of moral objections to the proven public health solutions and fear of stigma attached to them.

Eric Marcus, the founder and host of the Making Gay History podcast, remembers that there was “pushback from gay people over the recommendations that gay people stop having sex or have safe sex. And there were people who said, ‘Well, you can’t tell us what to do.’ So that’s very familiar in the middle of the COVID epidemic[s].”

“There was understandably great skepticism: ‘Where is that info going?’ ‘If I go get tested, what happens with that information?” as Jim Bunn, the co-creator of World AIDS Day, describes the fears of getting tested back then. A large part of the motivation behind starting World AIDS Day in 1988 was to make it more socially acceptable to talk about topics shrouded in misinformation, prejudice, and fear, and shift the discussion from AIDS as spreading among highly stigmatized groups to emphasizing its risk to the population more broadly as a sexually-transmitted disease.

After all, the hesitance to getting tested among gay men was tied to the stigma of the virus. Back then, for example, William Dannemeyer, an ultraconservative California Republican congressman, spoke about quarantining AIDS patients on an island in the South Pacific.

“If you’re a gay man, facing losing your job, losing your health insurance and maybe even being rounded up to be put on an island, you’re not going to particularly cooperate with public health forces, to have contact tracing to try to limit the spread of this disease,” Waxman says.

Additionally, much like methods to contain COVID-19 have received public and political pushback, practices that had proven effective in slowing the spread of AIDS faced intense scrutiny. In its Feb. 15, 1988, issue, TIME highlighted criticism of a new NYC plan to give drug users sterile needles, quoting Harlem pastor Rev. Calvin Butts arguing that “To distribute needles is to cooperate with evil. It is a step to legitimatizing heroin use.”

Two years later, at the Sixth International Conference on AIDS, experts still marveled at the still “hostile” resistance to efforts to educate young people about safe-sex practices, especially from conservative U.S. Senator Jesse Helms (R-NC).

“Wide use of condoms and distribution of sterile needles to addicts could stall the epidemic. But efforts to encourage such measures have been hampered by conservative politicians, who are squeamish about sex education and clean-needle programs,” TIME reported in the July 2, 1990, issue.

In the Feb. 16, 1987, issue TIME reported, “Conservative leaders see it as a summons to chastity or monogamy. Many people, dealing with the absolute death sentence that AIDS imposes, consider it a vague sort of retribution, an Old Testament-style revenge…An Atlanta executive concludes, ‘We are paying for our sins of the ’60s, when one-night stands and sex without commitment used to be chic.'”

Another tragic similarity between AIDS and COVID-19 is how each has disproportionately affected Black and Latino populations. By and large, the highest rates of new HIV cases are in the southern states that did not to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. The highest rates exist where the poorer, rural medical centers are less equipped with the latest drugs and treatments, and which treat patients who can’t afford them. “Communities of color and African-American communities have never gotten the resources that they need to fight the epidemic effectively,” says Dan Royles, historian and author of To Make the Wounded Whole: The African American Struggle against HIV/AIDS. “The changes that would be necessary are systemic.”

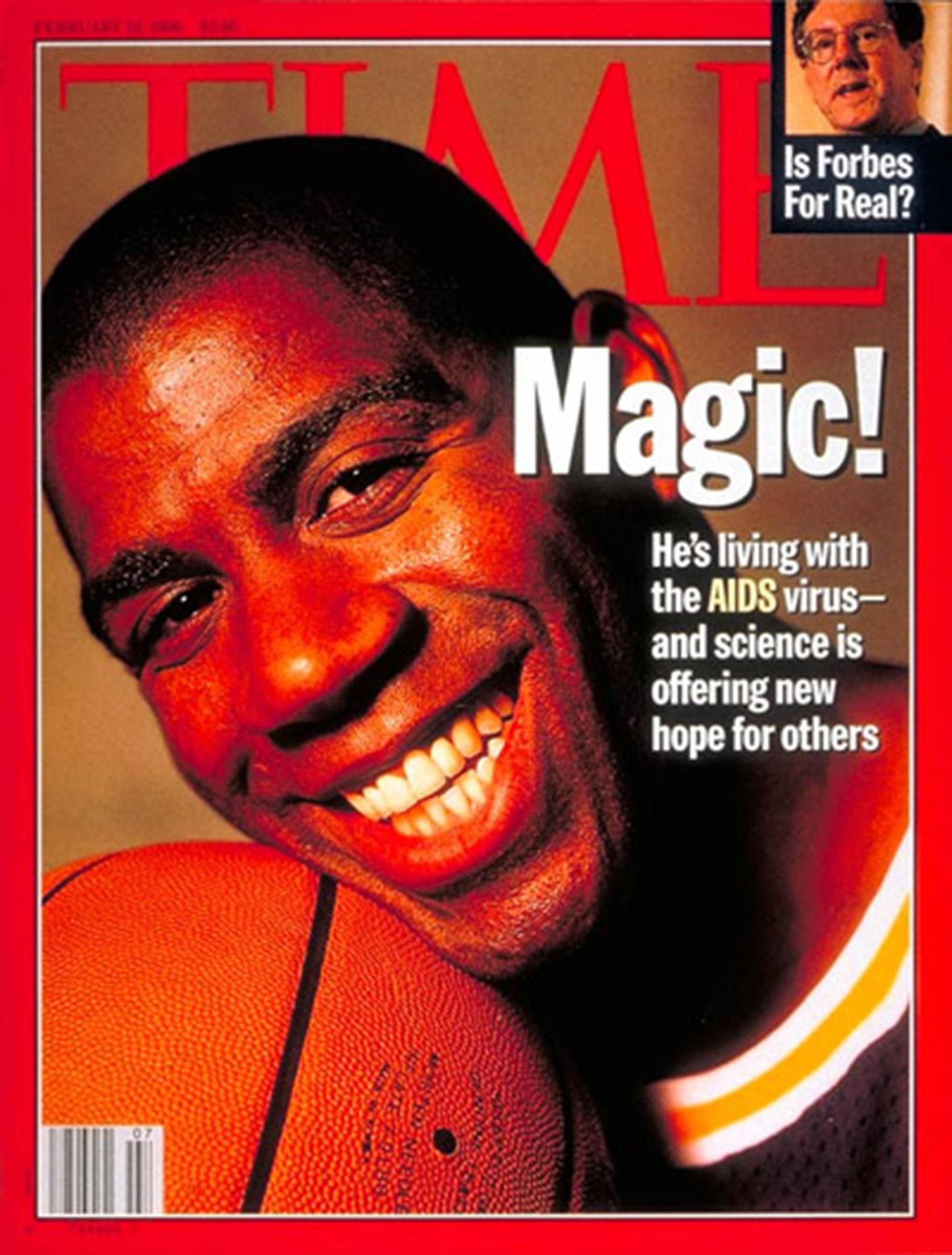

The 1990s saw key breakthroughs in treatments and public health awareness campaigns. After L.A. Lakers star Magic Johnson revealed in 1991 that he contracted HIV through unprotected heterosexual sex “made a difference” in terms of underscoring the seriousness of the threat of contracting HIV in the heterosexual population. FOX Broadcasting became the first national broadcaster to accept paid condom ads as long as the spots emphasized the health benefits and not birth control. Most importantly, in 1995, scientists discovered that a combination of drugs enables HIV patients to live a near-normal lifespan, and those regimens were made available to HIV/patients the following year. In 2019, there was a 23% decline in new HIV infections since 2010. But there is still no vaccine, and no cure, and AIDS still disproportionately affects Black and Latino populations.

World AIDS Day has become an annual occasion to remind the world that the AIDS epidemic is not over. Advocates hope that when the COVID-19 pandemic ends, people won’t forget the AIDS epidemic is still ongoing.

No matter the disease or population or differing levels of stigma, “the principles are the same,” Curran says. “What you need to do is have the best, transparent, scientific information and have it be updated all the time. You have to have consistent messaging, and you have to have trusted people on both sides giving the messages.”

With reporting by Suyin Haynes

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com