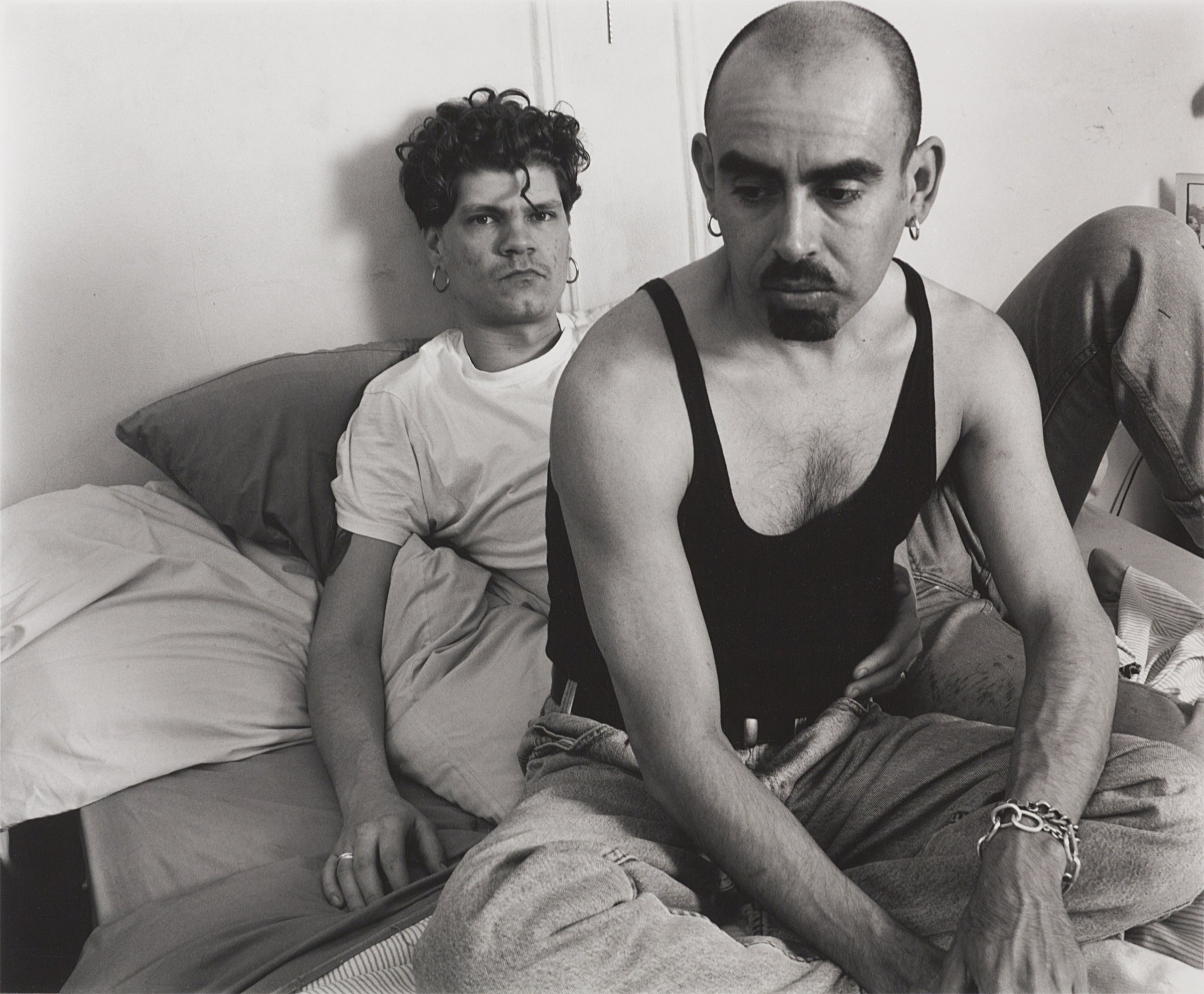

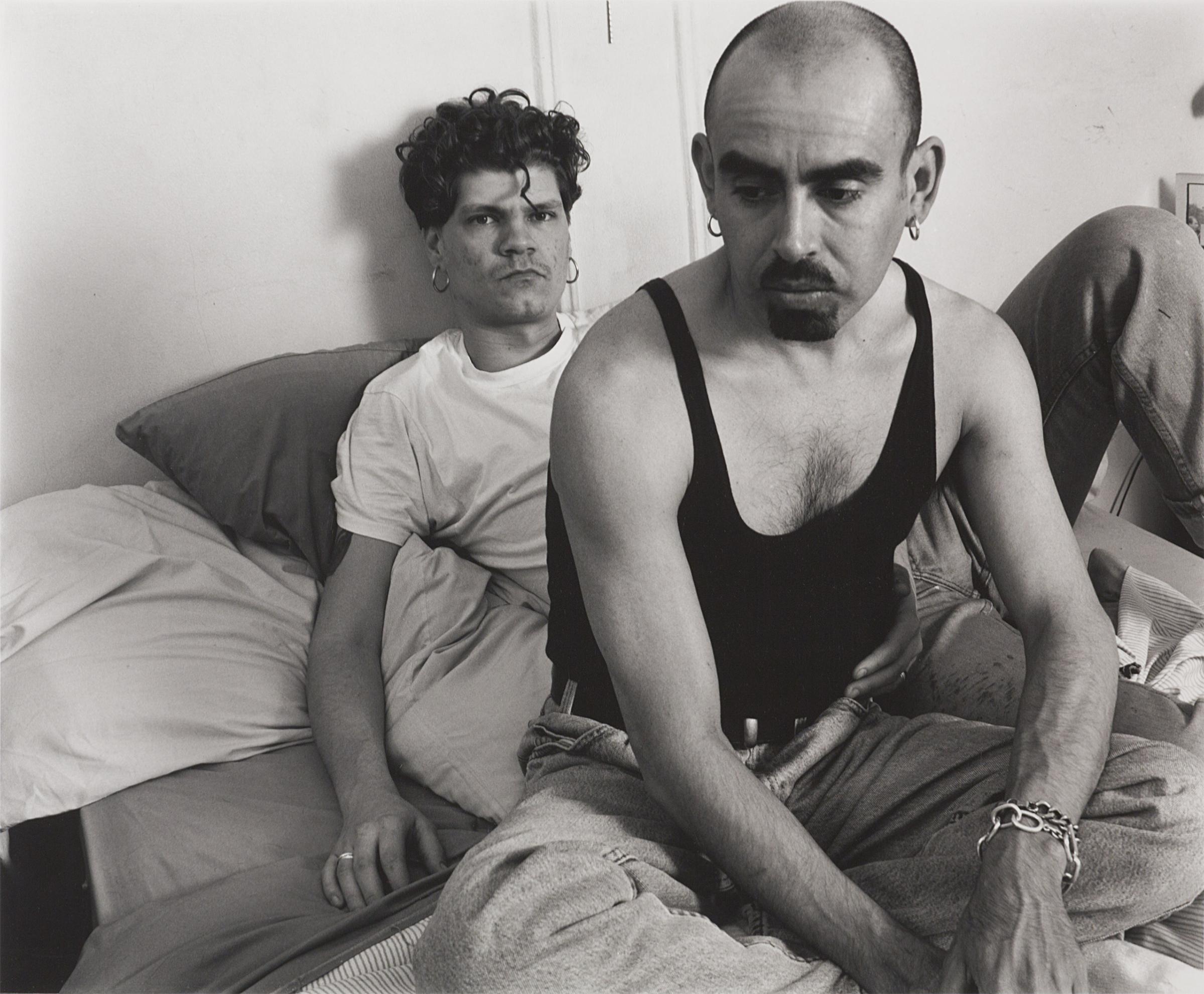

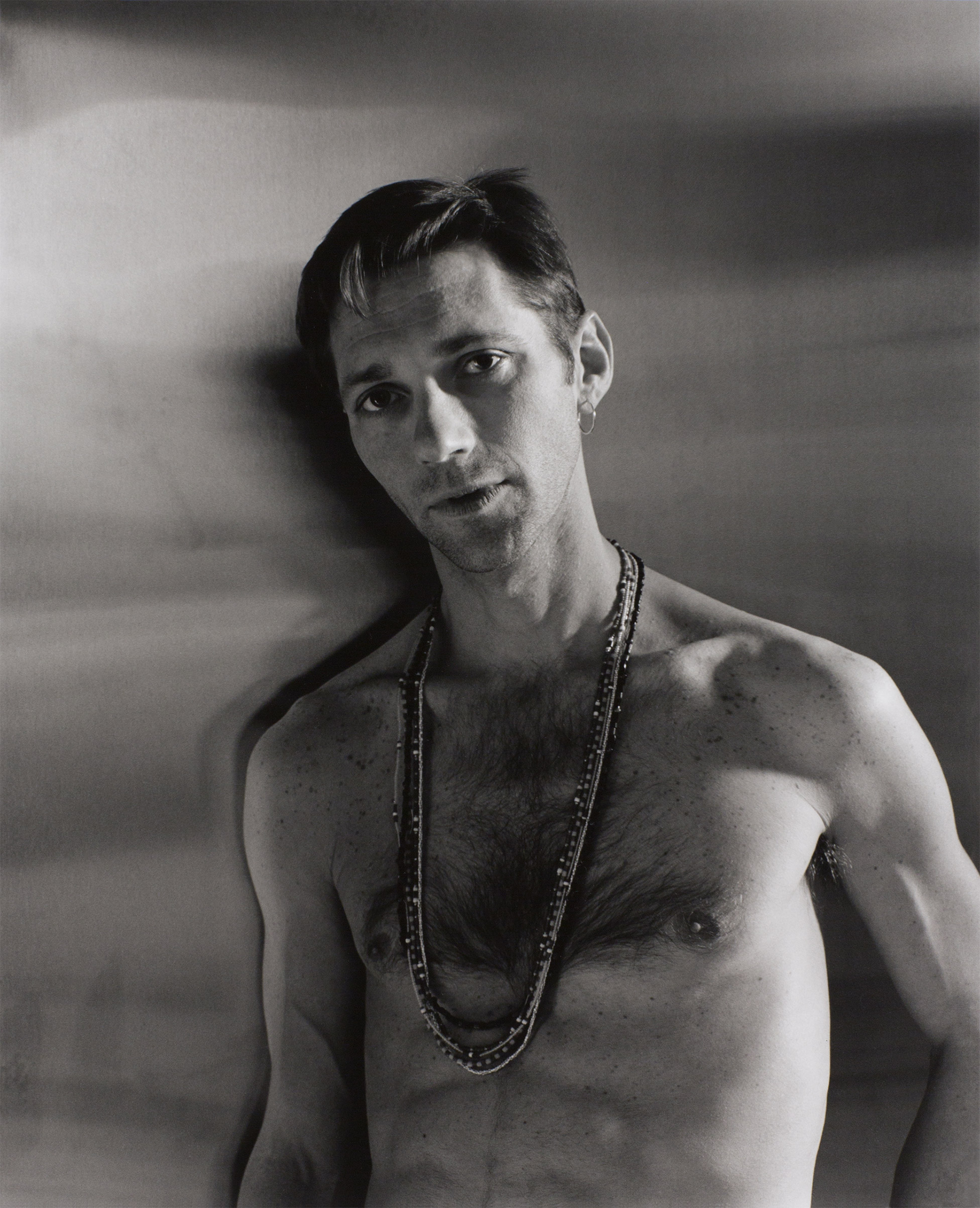

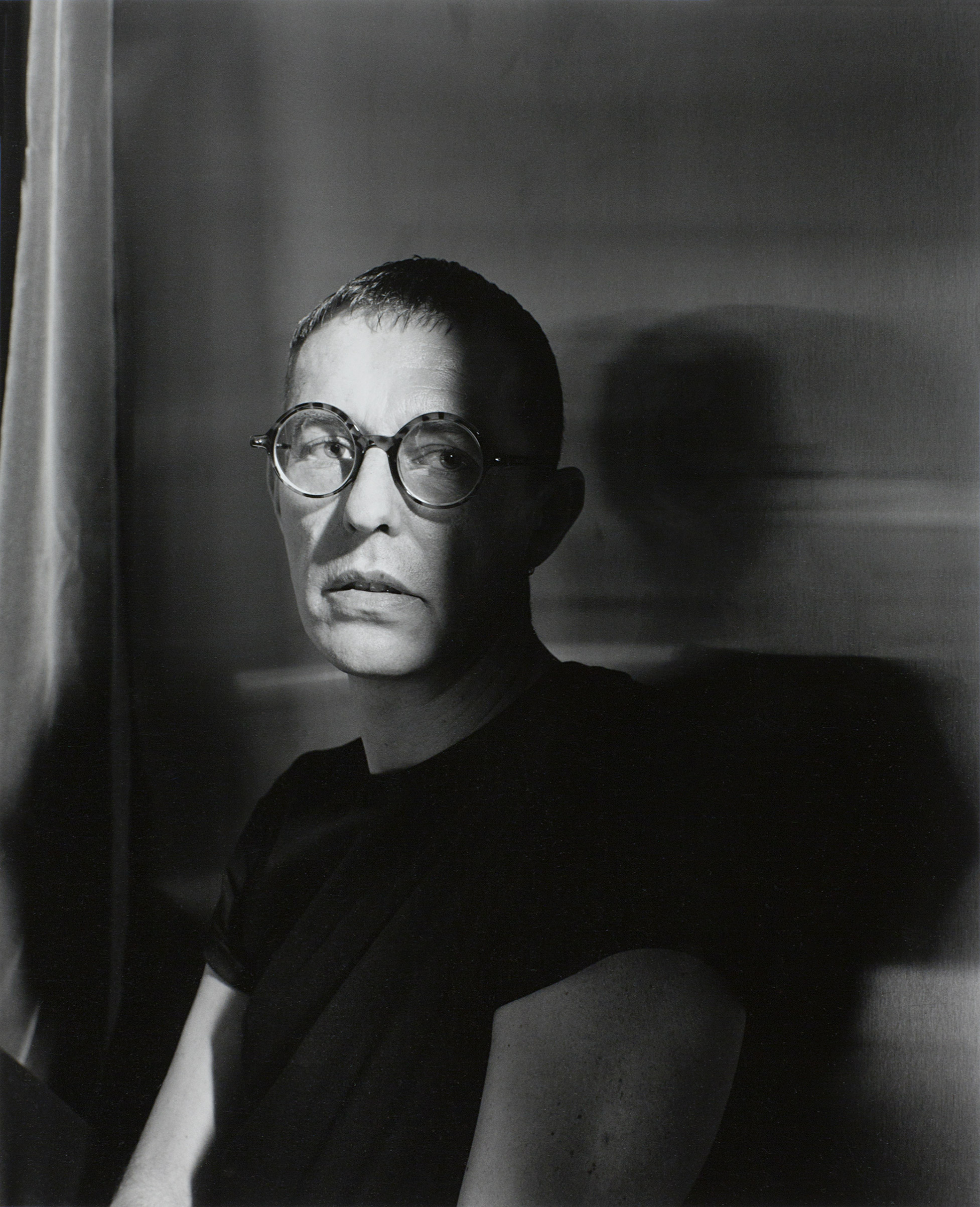

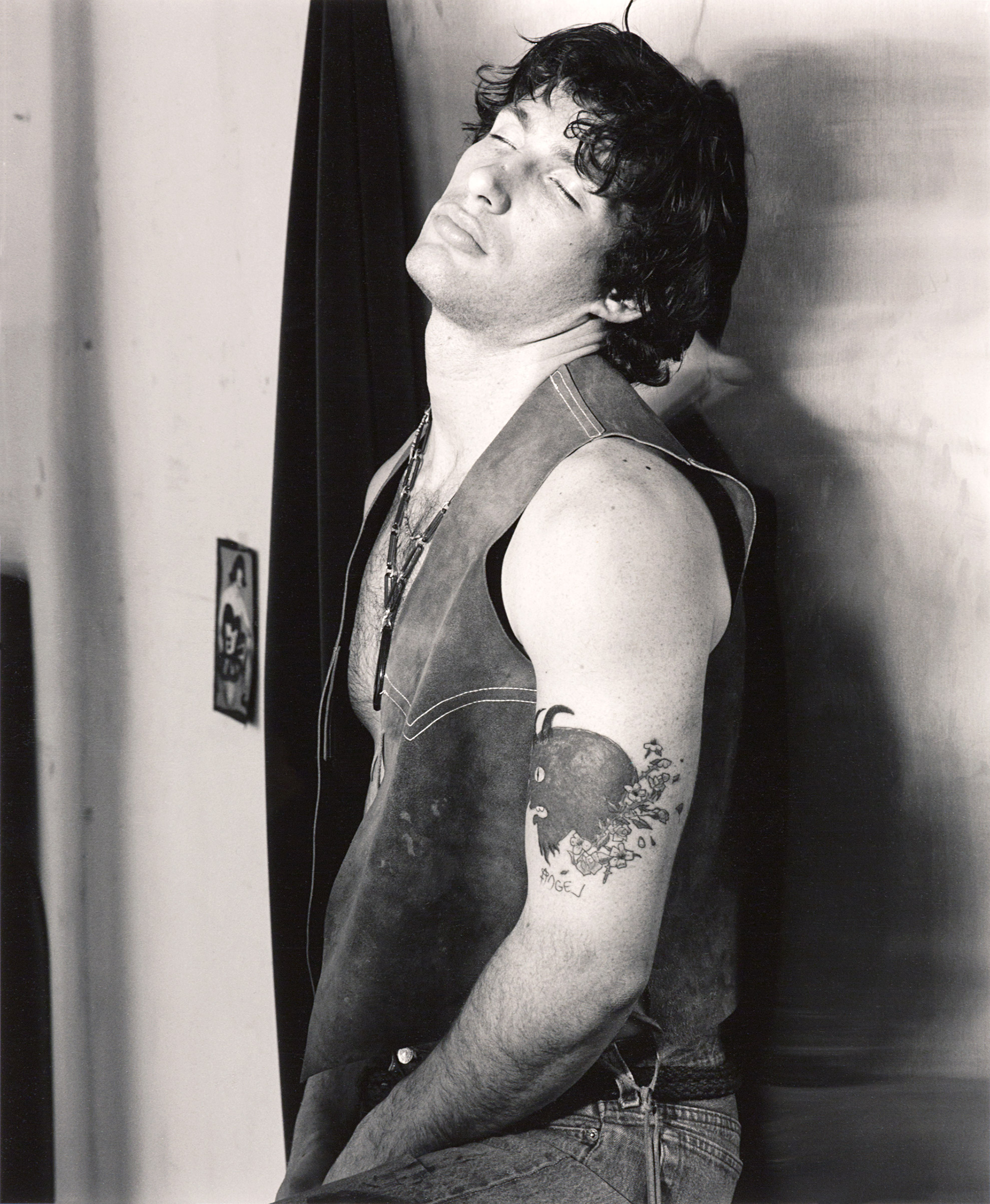

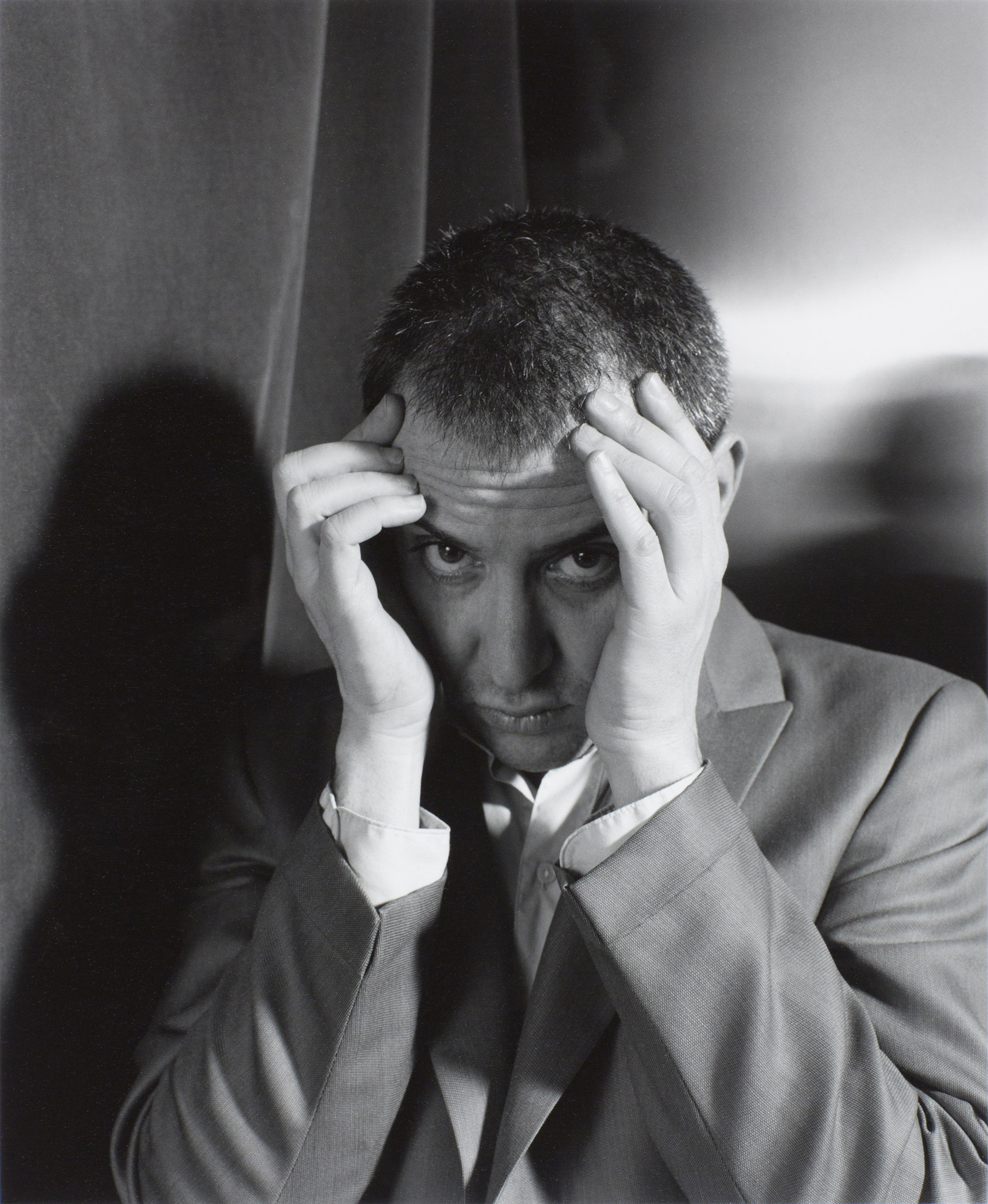

It was not until decades later — after drug advances and cultural changes had dulled the sharp edge of the AIDS crisis, after the disease and those who fought it became something that many people saw as history — that the photographer Stephen Barker realized that he had been creating a photo project about AIDS and the people he met at ACT UP, the AIDS advocacy group.

Barker had followed some friends to an ACT UP meeting in late 1988 and would end up being involved with the organization for the next several years, especially through his work as what he calls a “foot soldier” for its needle-exchange program. It seemed natural to start photographing his friends and comrades there, accumulating their portraits over time. But he says it was not until this past summer, when he began editing those photographs for a gallery show, that he saw that body of work “pull away” from the rest of his photography and become something separate.

“It isn’t a fair representation of everyone in ACT UP. It’s really just a handful of people who were among my friends. But on a spiritual level I think it says something about us,” Barker tells TIME. “There’s a lot of anger, a lot of push and pull and the heat of the moment and confrontations, and it’s terribly important, but there’s something behind all of that. There’s an understanding of the people involved that they are actors in history.”

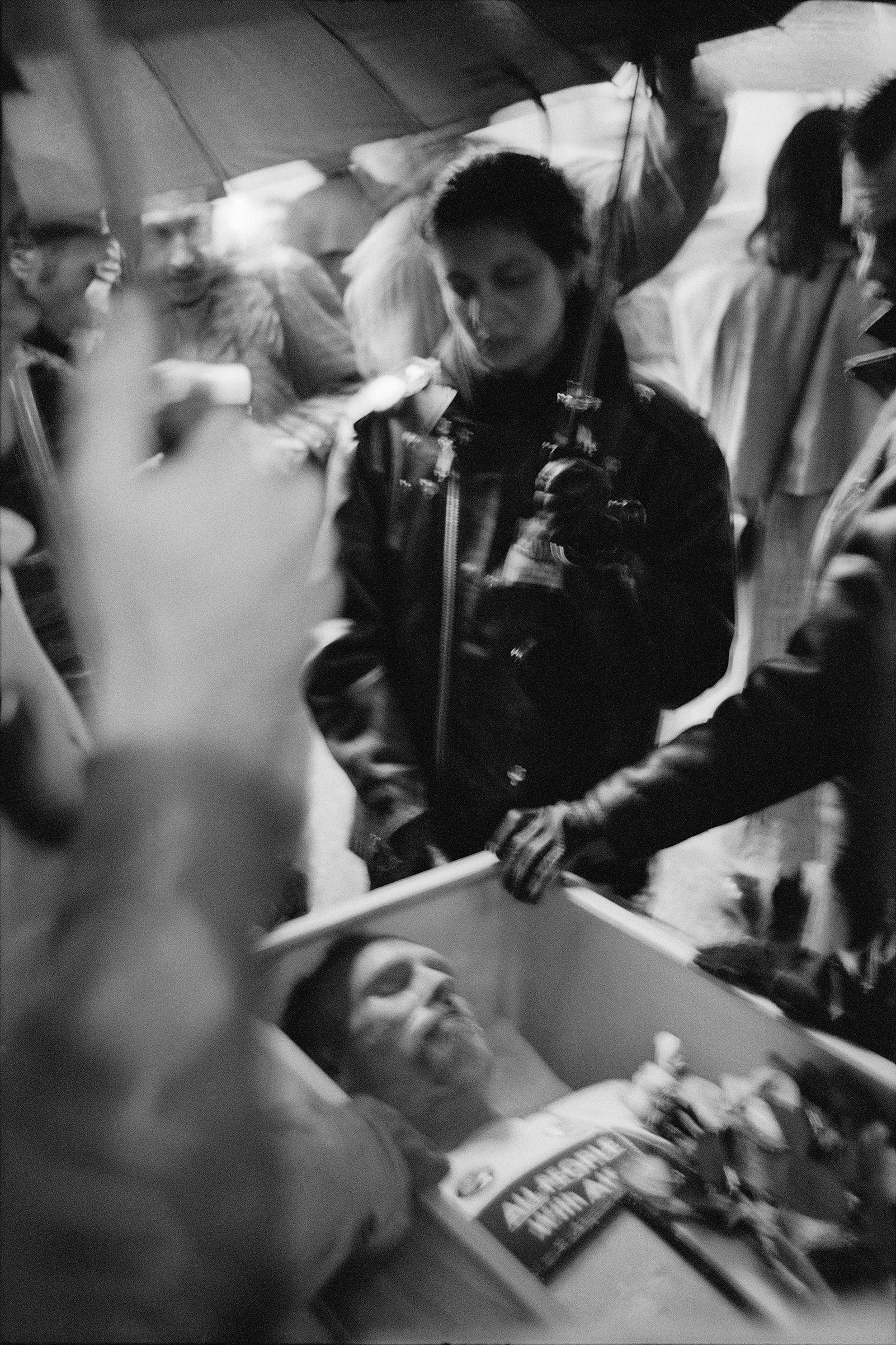

Those photographs will be exhibited at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York City from Sept. 14 through Oct. 28. Barker has also put together a book, Funeral March, of the photos he took documenting an event in which the body of Mark Lowe Fisher was brought in an open coffin to New York City’s Republican National Committee headquarters right before the 1992 presidential election.

Fisher had known that death was coming, and he wrote about why his funeral should be a time primarily to speak up, not to mourn.

“I have decided that when I die I want my fellow AIDS activists to execute my wishes for my political funeral,” Fisher wrote, in a statement, “Bury Me Furiously,” available on ACT UP’s website. “I suspect — I know — my funeral will shock people when it happens. We Americans are terrified of death. Death takes place behind closed doors and is removed from reality, from the living. I want to show the reality of my death, to display my body in public; I want the public to bear witness. We are not just spiraling statistics; we are people who have lives, who have purpose, who have lovers, friends and families. And we are dying of a disease maintained by a degree of criminal neglect so enormous that it amounts to genocide.”

Fisher’s funeral was one of a series of events that ACT UP organized in that period in order to force the American public, particularly politicians, to confront the literal life-and-death nature of the issue.

“It was amazing how much it took to rise above the mainstream din to be recognized. It required intense creativity and outlandish demonstrations,” Barker says. “It was wildly sad — to be so public, so confrontational, about your grief, to mix it up with anger and frustration. The whole thing was so naked.”

For the photographer, the physical difficulty of the act of the funeral march (“A body isn’t light,” he points out) combined with the physical reality of the moment, a rainy dusk, created a “tug of war” between his presence at such an emotional event and his feeling at the time that he was not adequately capturing it. Working with an unfamiliar camera, as the light faded, he says that he could hear the automatic exposure times lengthening, and knew the pictures would be blurry. In the moment, he felt “beyond caring” about the idea that the images might not be good. It wasn’t until later that he came to see their streakiness as a success.

The passing years, then, have changed Barker’s own relationship with the photographs. When he looks at them now, he says, it’s almost as if assessing work created by somebody else. But, at the same time, that moment around the turn of the 1990s feels newly fresh. In today’s political climate, he says he senses once again the same feeling that created ACT UP and such dramatic demonstrations as the funeral march.

“The situation then is really parallel to the situation now in several broad ways — the tension I think most of us wake up with every day, about Oh my god, what happens now,” Barker says. “[That situation] was true back then, except it was even more underscored because your life and the life of your friends was at risk. That constant pressure just needs somewhere to go”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com