Election Day 2020 will be unprecedented in any number of ways, but it won’t be the first time the U.S. has held elections during a global pandemic—or the first time a public-health crisis has changed the way campaigning and voting take place.

As the midterm elections of 1918 approached, World War I was winding down, but a new strain of the flu was surging. It had been spreading earlier in the year, but is believed to have mutated into a more deadly, more contagious strain that fall.

Data analyzed by Tom Ewing, a professor of history at Virginia Tech, reveal that death rates in northeastern cities had spiked in late September and mid-October in 1918, and had sharply declined by Election Day on Nov. 5, while West Coast cities were in the throes of ongoing outbreaks.

“In much of the country, particularly the East Coast and the upper Midwest, the epidemic is really on the decline by early November,” says Ewing. “There are still some local restrictions, but generally there is a sense in a lot of East Coast cities [that] if it’s not over, at least it’s been contained and is not a real concern. On the West Coast, in the mountain states, to some extent the Southwest, there are quite a few cases and quite a few restrictions in early November.”

So it makes sense that, in the run-up to the election, the extent to which the flu affected campaigning depended on where voters lived. Photos of Election Day throughout New York State show civilians, soldiers, sailors and even gubernatorial candidate Al Smith standing next to one another, sharing candy, not wearing masks. But in other areas, the flu played a major role in shaping the campaign season.

Then, as now, in-person campaigning, speeches, rallies, and gatherings to watch the returns were halted or severely restricted. Just as Democratic Vice Presidential nominee Kamala Harris paused campaign travel on Thursday after two staffers tested positive for COVID-19, and other 2020 campaigners swap indoor events for virtual events, 1918 campaigners had to move away from in-person methods of getting their messages out. Nationwide, candidates and campaign managers did more interviews, says J. Alexander Navarro, Assistant Director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan, and used the written word to communicate with voters. “Direct mailings had been used before, but this gets ramped up as a result of candidates not being able to meet directly with voters,” he says.

“The campaign has been most unusual this year in that it has been one carried on principally through literature,” declared the Nov. 2, 1918, edition of Utah’s Deseret Evening News, one of many newspaper articles in the Center for the History of Medicine’s digital archive the Influenza Encyclopedia. “State headquarters have employed large corps of workers to distribute reading matter throughout the state in behalf of candidates for justices of the supreme court and congressmen. In some cases, personal canvassing and visiting has been done, but this has proved not altogether successful inasmuch as the state health board has discouraged such procedure because of the prevalence of Spanish influenza and the subsequent ban placed on public gatherings of all kinds.”

Similarly, in California, the Oakland Tribune reported that “letter-writing, advertising, and telephoning took place instead of speech-making.”

The pandemic wasn’t a political football the way it is today. President Wilson never publicly addressed it, and the federal government was not expected to play a significant role in individuals’ healthcare matters. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention wasn’t founded until 1946, and Medicare and Medicaid date back to the Great Society legislation of the 1960s. However, decisions about which public places stayed open or closed did get political. Throughout 1918, states had been ratifying what would become The 18th Amendment, banning the manufacture, sale, and transportation of “intoxicating liquors.” Prohibition advocates, who had long cast saloons as a threat to public health, were thrilled when cities closed them to curb the spread of the virus. (On the flip side, whiskey was seen as a treatment for influenza, and police and bootleggers alike kept hospitals stocked with confiscated liquor.)

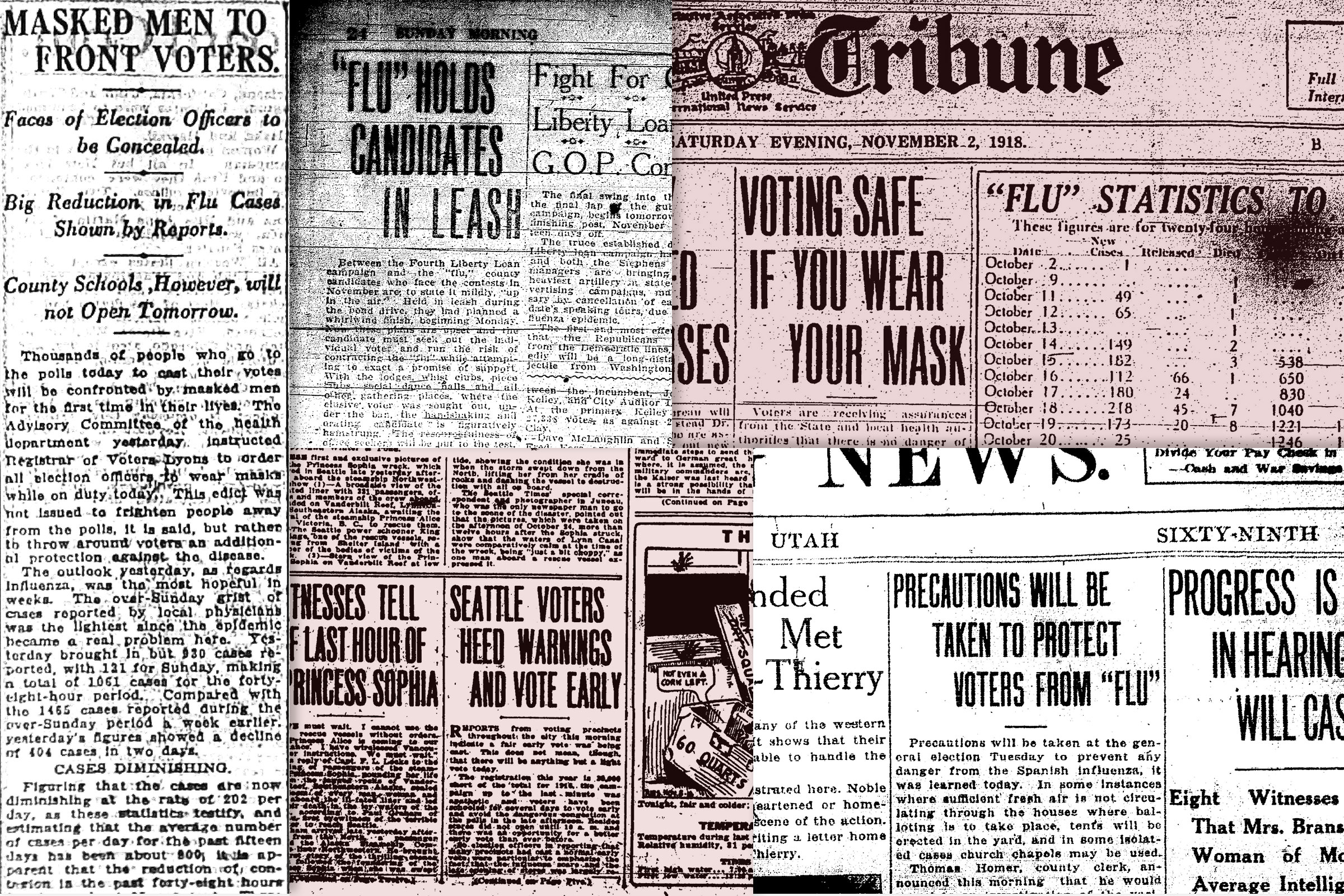

The closure of those spaces disrupted normal campaign tactics. Oct. 20, 1918, Oakland Tribune article “‘Flu’ Holds Candidates In Leash” informed readers that “With the lodges, clubs, social dance halls, and other gathering places where the elusive voter was sought out under the ban, the handshaking and orating candidate is figuratively hamstrung.”

When Election Day rolled around, the pandemic continued to shape voter behavior, and many of the basic precautions taken at polling places are the same as those taken in 2020.

In Seattle, citizens made a point of getting to their polling places earlier in the day to “avoid the dangerous congestion…in the late afternoon.” In Salt Lake City, tents replaced some poorly ventilated polling places. In Oakland, Calif., the Election Day edition of the Oakland Tribune declared it “One of the Queerest Elections in the History of California.” Election officials faced a shortage of poll workers because so many who had signed up had come down with the flu, and struggled to find replacements because people were afraid of getting sick.

Local health officials tried to reassure the public that it was safe to vote. “Thousands of people who go to the polls today to cast their votes will be confronted by masked men for the first time in their lives,” the Los Angeles Times reported in its Election Day edition. “This edict was not issued to frighten people away from the polls, it is said, but rather to throw around voters an additional protection against the disease.”

“There is not the slightest danger in voting if you wear your mask,” health officials in Oakland said in a statement on the front page of the Nov. 2, 1918, Tribune. “If you are staying home you are not being benefited by the fresh air and sunshine that you will enjoy performing your patriotic duty as an American Citizen.”

The city enforced the mask-wearing mandate too. About a dozen men who were arguing about election returns were each fined $10 (which would be about $185 in Sept. 2020) for removing their masks.

Such reassurances in newspapers were necessary to get out the vote, says Christopher Nichols, a historian of the Progressive Era and Director of the Oregon State University Center for the Humanities. “Americans are fearful. They didn’t get clear, rapid, coherent communication from the Wilson Administration or Surgeon General Rupert Blue,” he says, “so they don’t know what advice to follow and need to have regular communication from journalists that polling stations will be open to have confidence to go out.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

But those tactics may not have been enough. The 1918 election saw a dip in turnout, though it’s impossible to say how much of that shift was attributable to the pandemic versus the fact that many American men were still abroad fighting in World War I. While turnout is typically lower in midterm elections than in general elections, turnout in the Election of 1918 was about 40%, down around 10% from the two previous midterm elections (in 1914 and 1910), according to Navarro.

In the end, Republicans won control of Congress, and the leadership change is partly why the U.S. did not ratify the Treaty of Versailles or join the League of Nations.

“The 1918 election is a referendum on an unpopular war, and the U.S. rebukes that war at the ballot box, ending hopes of Democrats ramming through much legislation and eviscerating Wilson’s claims to popularity about his war effort and peacemaking,” says Nichols.

The war would end just days after the election, with the armistice arriving on Nov. 11. The pandemic, however, despite appearances to the contrary, continued for more than a year, and ultimately killed about 675,000 Americans and at least 50 million people worldwide, while infecting about 500 million people—one-third of the global population. Whether voting in person caused any spikes in cases is likewise impossible to say, as many cities relaxed their gathering restrictions to celebrate the end of World War I. In Denver, for example, the city began to reopen before Election Day and Armistice Day, and shortly thereafter residents found themselves facing a death rate worse than the beginning of the deadly second wave of flu.

“We’ll never know how much the combination of people turning out to vote in person—and then roughly one week later, gathering to celebrate the end of the war—exacerbated spread and suffering,” says Nichols.

Today, Americans have many more opportunities to vote that can help mitigate the “dangerous congestion” feared in 1918, from voting by mail to voting early at satellite polling places. As TIME has previously reported, masks and social distancing saved lives back then, and can do so again this Election Day.

And the fight to prevent future pandemics continued well after Election Day 1918, as it will this year too. Thousands of telegrams flooded that newly elected Congress in the summer of 1919, urging lawmakers to support a bill to fund an investigation to avoid a repeat of the pandemic—and reminding them that another Election Day would arrive soon enough.

“There is time for Congress to do something toward helping health officials, physicians, and others interested in public health to prevent a recurrence of the flu epidemic—to halt the coming of another DEATH MONTH,” declared a front-page article in North Dakota’s Bismarck Tribune, which was shared with TIME by researchers at the genealogy website MyHeritage. “But Congress must act quickly. Usually Congress does NOT act quickly. Mostly Congress takes its time and acts when it gets good and ready. Often Congress needs a prodding from the home voters.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Harris Battles For the Bro Vote

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com