Just after midnight on a grand stage in Iowa, Pete Buttigieg went for it. “By all indications,” the Democratic presidential candidate and former mayor of South Bend, Ind., declared, “we are going on to New Hampshire victorious!” Supporters chanted, “I-O-W-A, Mayor Pete all the way!” as Buttigieg gave a soaring speech about unity and change, boasting of a new American majority that could beat President Donald Trump.

The spectacle was a bit surreal, and not only because the campaign could barely fill an Iowa coffee shop a year ago. Buttigieg had not officially won anything yet. While his staffers had compiled internal numbers suggesting a win, official results from the Iowa Democratic Party had yet to arrive because of glitches with a smartphone app and other issues that delayed final election results from Iowa’s more than 1,700 caucus precincts well into the week.

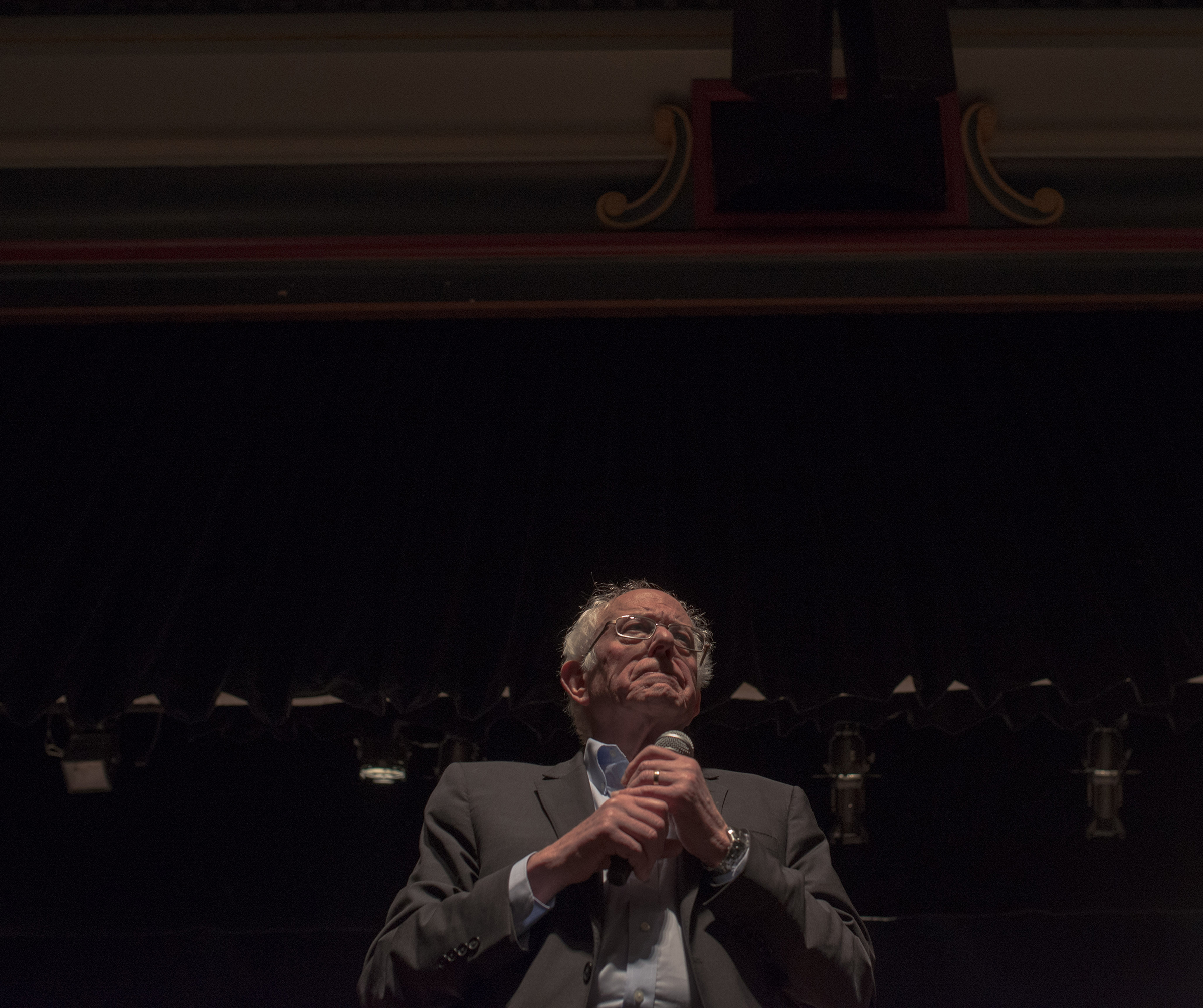

But as the count came in over the ensuing, Buttigieg appeared to be right. With more than three-quarters of the caucus vote tallied as of Feb. 5, he was projected to edge Senator Bernie Sanders in the official metric for victory, state delegates. Sanders was projected to have won the raw first-round vote in the quirky multistage caucus system Iowa clings to, allowing the Vermont liberal to claim a measure of victory as well.

The split decision in Iowa was a stumbling start to what is now likely to become a long, hard-fought slog to the Democrats’ convention in Milwaukee. For a year now, a record-breaking and well-credentialed field of Democratic candidates, packed with governors, Senators, businessmen and a former Vice President, has spent tens of millions of dollars and untold hours crisscrossing Iowa’s frozen cornfields, industrial cities and college towns, sparring over competing visions for the party and seeking to persuade voters that they were best positioned to topple Trump. For a gay 38-year-old former mayor of a midsize city and a 78-year-old democratic socialist to emerge on top in Des Moines is a sign of how far the party has to go to settle the battle for its future.

Iowa traditionally winnows the primary field, codifying voter preferences and persuading low-polling candidates to give up. This time, not a single candidate dropped out, and the Democrats flew out of Des Moines with the picture more muddled than ever. Rather than moving toward a consensus nominee, Democrats appear more fractured and uncertain than before. It’s as if the party’s collective anxiety about November has paralyzed it, rendering it unable to make a decision.

Sanders, who appears better positioned than Buttigieg in the upcoming contests in New Hampshire and beyond, is now the closest thing the party has to a front runner. “Bernie is definitely in the driver’s seat for the entire primary,” says Ian Sams, former spokesman for Kamala Harris and a veteran of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign. The Democratic nomination is as likely as not to go to an avowed enemy of its establishment who is not even a member of the party.

Lagging Sanders and Buttigieg was Elizabeth Warren, the Massachusetts Senator whose ambitious liberal policy proposals rocketed her to the top of the field before voters began to fret that Trump would wield them against her. Former Vice President Joe Biden, long the national polling leader, hobbled to a distant fourth-place finish.

If the results were a surprise, the bigger shock was how long they took to arrive. The caucuses were marred by technological and logistical problems that undermined confidence in the result, though there was no evidence of irregularities in the count itself. Turnout was lower than many expected, projected not to exceed the caucuses of 2016, which also ended in procedural chaos.

Trump and his allies took the occasion to gloat over the Democrats’ misfortune. On the eve of his impeachment acquittal, the incumbent’s approval rating hit a career high. And Mike Bloomberg, the billionaire former New York City mayor who’s gaining in national polls after pumping some $300 million into what once appeared to be a quixotic effort, announced he would ratchet up his massive national staff and advertising push, casting himself as the savior who will rescue the party from its early-state confusion.

Biden seemed relieved to have left Iowa behind. “I’m not gonna sugarcoat it, we took a gut punch,” he said on Feb. 5 in Somersworth, N.H. His weak showing hurts his central argument, that he’s the candidate most likely to defeat Trump, and it amplified concerns about his ability to go the distance in the primary.

The campaign tried to project confidence, but just a week earlier, Biden himself had said it would be difficult for a candidate who finished more than 7 percentage points behind the winner to survive; the preliminary results showed him 11 points behind Buttigieg in the delegate race. Biden’s senior hands argued he would get another look from the party’s center thanks to Sanders’ surge. But there’s only so long a campaign can survive without results. Biden’s fundraising already was lackluster; Iowa wasn’t going to help.

Warren’s third-place showing left her in a tough spot, a distant second to Sanders among liberals, with little apparent success adding moderate voters. Warren had invested heavily in Iowa, building a field operation even rival campaigns hailed as the best in the state. But her conditional embrace of a Medicare for All health plan that would upend America’s existing insurance system turned off moderates without winning over Sanders supporters.

In the final days in Iowa, Warren tried to position herself as a unity candidate, arguing her populist proposals would draw crossover votes in the general election. She pointed to women candidates’ success in the 2018 midterms to argue that a female nominee would be the best matchup against Trump. As she prepared to leave Iowa, Warren touted her campaign as “built for the long haul,” noting it has staff in 31 states. “The path to progress runs through courage, not fear,” she told her supporters.

The primary beneficiary of Biden’s slide and Warren’s strategic missteps was Buttigieg. “Pete has been making a fresh-start, new-generation electability argument,” says Democratic strategist Bryan DeAngelis, who is neutral in the race. “It’s a different electability argument than Biden’s, and it is appealing to a large bloc of Democrats.”

A hyperdisciplined intellectual who may be the party’s most polished performer since Barack Obama, Buttigieg leaned on the power of storytelling, betting that voters who are tired of partisan division are eager for reassurance about the future. In the weeks before the caucuses, he spent much of his time in rural counties that swung from Obama to Trump, promising to “put the chaos behind us” and recruiting former Republicans alienated by the President. Like Obama, he pitched a vision of hope and unity, arguing that America is flawed but forgivable, that her sins are venial but not mortal, and that bigotry can be melted by love. “Our message about belonging is designed to make everyone feel welcome, and my own search for belonging of course partly has to do with being different because I’m gay,” he tells TIME.

Buttigieg hoped his Iowa showing would translate to new traction in New Hampshire. “The idea of electability has to be centered somewhat around who can bring people together and who can build a big-tent Democratic Party,” Lis Smith, a senior Buttigieg adviser, said at a roundtable hosted by Bloomberg News. “We are the only campaign that’s actively aware of that and actively pursuing that.”

For his part, Sanders has sought to expand beyond the zealous coalition that powered his upstart challenge to Clinton in 2016. This time, Sanders built a ground game that his campaign says knocked on 500,000 doors in Iowa in the month before the caucuses and courted Latinos with a blizzard of bilingual mailers, a variety of Spanish-language ad buys and 22 paid Latino staffers in the state. Chuck Rocha, a top Sanders adviser, estimates the campaign spent $1.5 million in bilingual outreach in Iowa alone.

The Sanders surrogate machine sustained him while he was stuck in Washington for impeachment. “It’s so important that we just keep our noses down and keep organizing and keep phone banking and knocking on doors and doing what we can,” Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez tells TIME, “because this thing is not over until the nomination is secured.”

The prospect that Sanders could triumph in Milwaukee freaks out the party’s pooh-bahs, who fear his far-left positions will alienate swing voters. “The Democratic Party has been asleep at the switch,” says Jonathan Cowan, president of the centrist think tank Third Way, who is actively trying to stop Sanders. It’s not too late to stop him, Cowan says, but Democrats have to treat him like a front runner and consolidate their support behind a single moderate candidate quickly. “If you wait until April or May,” he says, “it will be too late.”

Mingled with the angst, however, is a fear that attacks on Sanders will only make him stronger, as many of his supporters thrive on antiestablishment fervor. The Iowa caucus confusion fed a related vein of conspiratorial thinking, as liberals on social media pointed to the failed app’s connections to the Democratic establishment as well as to the Buttigieg campaign as evidence of some anti-Sanders plot.

The coming states appear to favor Sanders. The Vermonter won New Hampshire by 22 points in 2016 and is polling well ahead of the Feb. 11 primary. Then it’s on to the Nevada caucuses on Feb. 22, where the Democratic electorate is heavily working class and Latino. In the past it has been strongly influenced by momentum from the first two states, making it potentially another Sanders stronghold. One key factor will be the powerful Culinary Workers Union, which represents the hotel and casino workers of the Las Vegas Strip and operates a formidable turnout machine, but has not yet endorsed a candidate.

South Carolina’s primary on Feb. 29 is dominated by African-American voters, and polls have strongly favored Biden. The Vice President’s campaign has regarded the state as a backstop. Black voters were a major weakness for Sanders four years ago, but his campaign has spent the intervening years making a major push for African-American votes and has made inroads, particularly with younger black voters.

With Super Tuesday, the delegate fight gets serious. The four early states are important for narrowing the field and establishing narratives, but only 4% of the party’s total delegates will be awarded in February. On March 3, when 14 states are scheduled to hold primaries, a staggering one-third of the total delegates will be awarded in a single day. By the time March is over, two-thirds of all delegates will be spoken for. “When we get to Super Tuesday after the first four states, we will be in a strong position,” says Symone Sanders, a senior Biden adviser.

But it’s here that Bloomberg is making his stand, a billionaire gate crasher loathed by the left who is blanketing the airwaves with ads that bash Trump and cast the candidate as a pragmatic, results-oriented leader. His strategy of skipping the first four contests is unprecedented but beginning to look prescient. After the Iowa mess, Bloomberg’s campaign said it would double its massive TV effort and boost its field staff to more than 2,000. And while populists like Warren charge he’s trying to buy the nomination, there’s evidence Bloomberg’s millions are making an impression on voters: he’s now polling in double digits nationally.

All the campaigns are girding for a delegate fight. The perennial nightmare scenario of an undecided race going into the convention appears likelier than it has been in recent memory. It all adds up to a party racked with anxiety on the eve of an election many consider the most consequential of their lifetimes. “The angst is so intense,” says John Norris, a Warren backer and former chair of the Iowa Democratic Party. “We are so concerned about getting it right. We feel an intense responsibility, we’re all talking about it. But there’s no definition of what it means to get it right.”

With reporting by Charlotte Alter, Philip Elliott and Abby Vesoulis/Des Moines

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Molly Ball/Des Moines at molly.ball@time.com and Lissandra Villa/Des Moines at lissandra.villa@time.com