A deeply divided Senate acquitted President Donald Trump at the end of his impeachment trial on Wednesday, with 52 Senators concluding the House’s allegations that he abused the power of his office did not necessitate his removal of office, and 53 reaching that conclusion on the charge that he obstructed Congress.

The Senate’s verdict renders Trump the third President in U.S. history to face impeachment charges in the House and be acquitted by the Senate. The final result came after nearly two weeks of a Senate trial encompassing dozens of hours of oral arguments and more than one hundred written questions from the Senators, and more than four months after the impeachment inquiry first began in the House.

Trump’s acquittal was nearly entirely along party lines. Every Democrat voted to convict Trump and all but one Republican voted to acquit him. Only Sen. Mitt Romney, a Republican from Utah, broke with his party and voted to remove the President from office by convicting him on abuse of power.

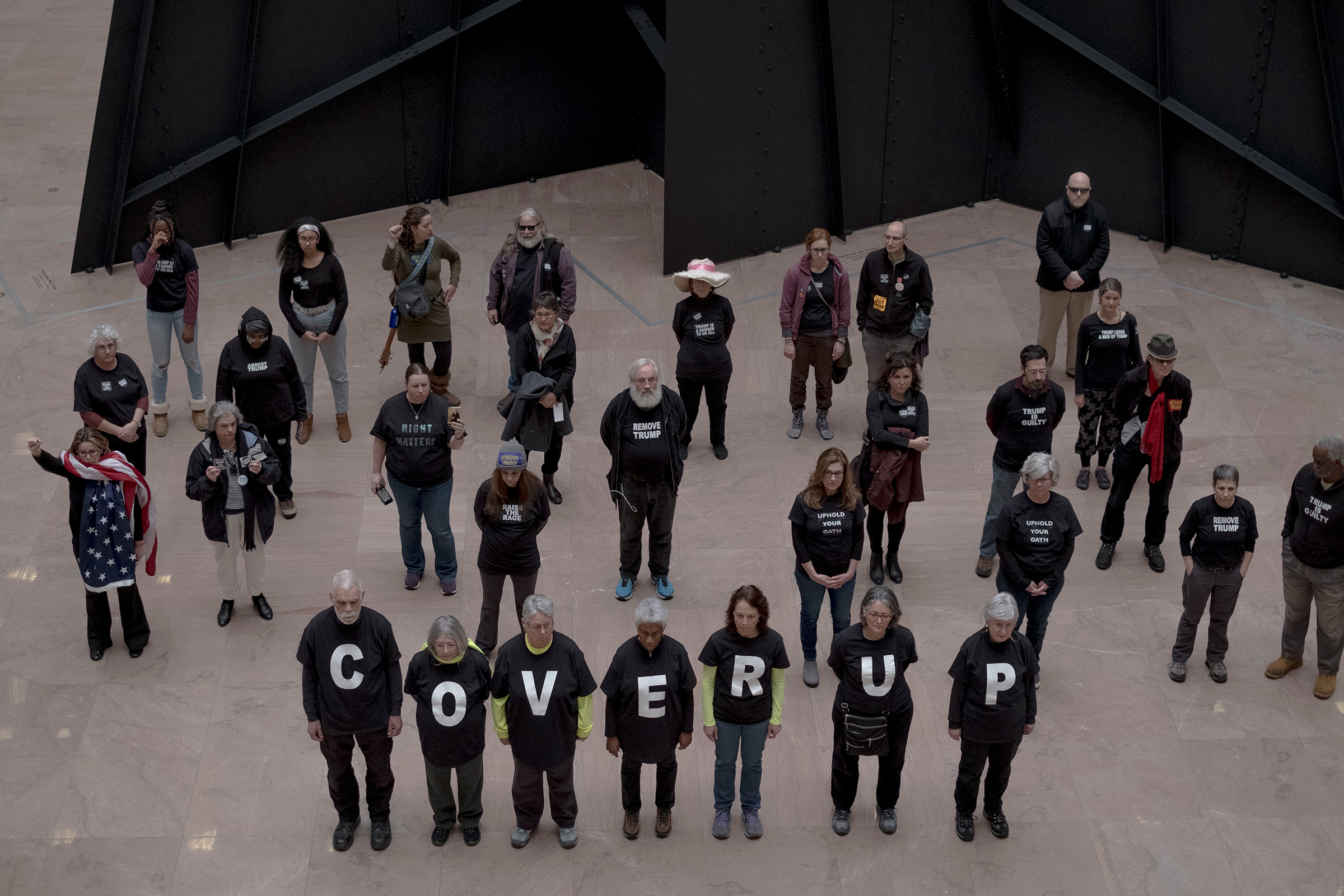

By the conclusion of the trial, there was only one thing on which weary lawmakers from both parties could agree: this impeachment has heralded a dangerous new hyper-partisan era that could damage the workings of government for a generation. Republicans said an impeachment process that was initiated and played out almost entirely along party lines was a disturbing use of a grave constitutional duty as a political weapon in an election year. Democrats said that Republican lawmakers had shirked their constitutional duties in their politically expedient support for Trump, even after multiple government officials testified that the President abused the authority of his office.

Inside and outside the Senate chamber, lawmakers said all three branches of government had been weakened by the partisanship on display since House Speaker Nancy Pelosi first announced the inquiry last September. Depending on their position, they warned that the presidency had been hampered by an impeachment that amounted to a political disagreement, that Congress had abdicated its responsibility for fairness, and that even the judiciary had become tainted by the bitter politics that had seized the impeachment process.

Senators from both parties sat grim-faced and serious during the proceedings, without any strong visible reaction from either side when Trump was officially declared not guilty by Chief Justice John Roberts. Senators Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, two moderate Democrats who at one point were considered contenders to break with their party and voted to acquit Trump, shared a moment together before the vote. Sinema approached Manchin in his seat and put a hand on his shoulder; they talked briefly, and Manchin stood up to hug her. Minutes later, they both voted guilty on abuse of power, officially making Romney the only senator of either party to break ranks.

“We have changed. The members of Congress have changed,” Rep. Adam Schiff, the House Democrats’ lead impeachment manager, lamented during his closing arguments. Members of Congress, he said, are “now far more accepting of the most serious misconduct of a president as long as it is a president of one’s own party. And that is a trend most dangerous for our country.”

Schiff’s final speech was one last attempt to try and persuade moderate Republicans to break with their party. It was a call that only Romney heeded, which technically made this the first bipartisan conviction vote of a president. But Romney knew it would be a futile gesture. “I acknowledge that my verdict will not remove the President from office,” he said in an emotional speech on the Senate floor before the vote. “But irrespective of these things, with my vote I will tell my children, and their children, that I did my duty to the best of my ability believing that my country expected it of me.”

But Republicans in both the House and Senate constructed their arguments on the opposite point. They argued not that senators should cross party lines to make a bipartisan judgment, but that Republicans should stick together in order to not endorse the House’s partisan vote to impeach the President based on charges that he had abused the power of his office by withholding aid to a foreign ally for his own political benefit, and then obstructed Congress’s efforts to investigate his conduct.

Trump’s lawyers argued that the prospect of lowering the threshold for impeachable conduct to something that is not a statutory crime and isn’t broadly agreed upon by both parties would mean that future presidents in a similarly divided government could be impeached over mere policy disputes. “If that becomes the new norm, future presidents, Democrats and Republicans, will be paralyzed the moment they are elected,” Trump lawyer Jay Sekulow warned on Jan. 29. “The bar for impeachment cannot be set this low.”

That ultimately appeared to be the stronger argument for some senators who had been on the fence. Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski, who joined Senate Democrats in opposing Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation in 2018 and who had been pinpointed as a possible Republican dissenter in the impeachment process, voted for acquittal for precisely this reason. The President’s behavior, she said in a floor speech announcing her decision this week, was “shameful and wrong,” but the House’s process was not an apt remedy for it. “The House rushed through what should have been one of the most serious, consequential undertakings of the legislative branch simply to meet an artificial, self-imposed deadline,” she said. “The House failed in its responsibilities.”

Like Murkowski, retiring Tennessee Sen. Lamar Alexander also argued that the risk of endorsing a partisan process in today’s polarized political climate by removing Trump from office outweighed the dangers that Trump’s actions posed. “The framers believed that there should never, ever be a partisan impeachment,” Alexander said in a statement on Jan. 30. “If this shallow, hurried and wholly partisan impeachment were to succeed, it would rip the country apart, pouring gasoline on the fire of cultural divisions that already exist. It would create the weapon of perpetual impeachment to be used against future presidents whenever the House of Representatives is of a different political party.”

And Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, in announcing his decision to acquit, said he was more concerned about the impact of the impeachment proceeding’s partisanship on the country’s future than in leaving Trump in office, even if he had sought foreign interference in the 2020 election, as Democrats claim. “Just because actions meet a standard of impeachment does not mean it is in the best interest of the country to remove a President from office,” Rubio wrote in his statement. “Can anyone doubt that at least half of the country would view his removal as illegitimate — as nothing short of a coup d’état? It is difficult to conceive of any scheme Putin could undertake that would undermine confidence in our democracy more than removal would.”

Democrats were just as concerned about where the government’s stark political divisions were taking the nation. They felt it prohibited their Republican colleagues in both chambers from even considering their case against the President. Up until last September, Pelosi had publicly resisted growing calls from the Democrats’ progressive voter base and liberal lawmakers to start impeachment proceedings as the White House resisted Congressional oversight, insisting that such a divisive effort must have bipartisan backing. “Unless there’s something so compelling and overwhelming and bipartisan, I don’t think we should go down that path because it divides the country,” she told the Washington Post last February.

Democrats knew the bar for amassing enough Republican support for a conviction might be, as Schiff put it in his closing arguments, “prohibitively high.” But they said that it was their constitutional duty to try to stop a Commander in Chief that presented a danger to the nation. And they still held out hope that some Republicans would support their efforts to do so, particularly after more than a dozen non-partisan bureaucrats and political appointees testified under oath that Trump’s efforts to run a shadow foreign policy in Ukraine undermined national security interests, strengthened Russia and set a dangerous diplomatic precedent. “We could not afford to stand on the sidelines in that instance,” Democratic caucus chair Hakeem Jeffries and an impeachment manager, said on Wednesday.

But it was not until the end of the Senate trial that a handful of Senate Republicans would even publicly say that Trump’s behavior was improper. For Democrats, who viewed Trump wielding the power of his office to solicit foreign interference in the next election as the greatest danger to the republic, the partisanship represented in the Republicans’ united front, which they argued was out of fear of the President or their own job security due to his enduring popularity, was just as concerning as the prospect of removal.

“As long as the president’s party is willing to stand behind him, there will be no accountability for any wrongdoing. None,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a Democrat from Massachusetts, told TIME. “That can’t be right. It just scissors the impeachment clause out of the Constitution.”

More moderate Democrats were equally perturbed. “Very early on I implored my colleagues in both houses of Congress to stay out of their partisan corners. Many did, but so many did not. The country deserves better,” Alabama Sen. Doug Jones, one of the most vulnerable Democrats up for reelection, said in a statement on his decision to convict the President.

By Wednesday, as the exonerated President shifted his energy back to his re-election campaign, it seemed the most indelible outcome of the third presidential impeachment trial in U.S. history might be the further deepening of political divisions in government and across the country. On Tuesday, Gallup released a new poll showing that during impeachment, Trump reached his highest ever job approval rating, at 49%. While Trump’s approval among Republicans hit 94%, it was just 7% among Democrats—the largest discrepancy ever measured, according to Gallup.

Going forward, lawmakers will need to find a way to continue to do their jobs in this disillusioned and divided workplace. “So many in this chamber share my sadness for the present state of our institutions,” said Murkowski. “It’s my hope that we’ve finally found bottom here.”

That sentiment, at least, crosses party lines.

—With reporting by Massimo Calabresi/Washington

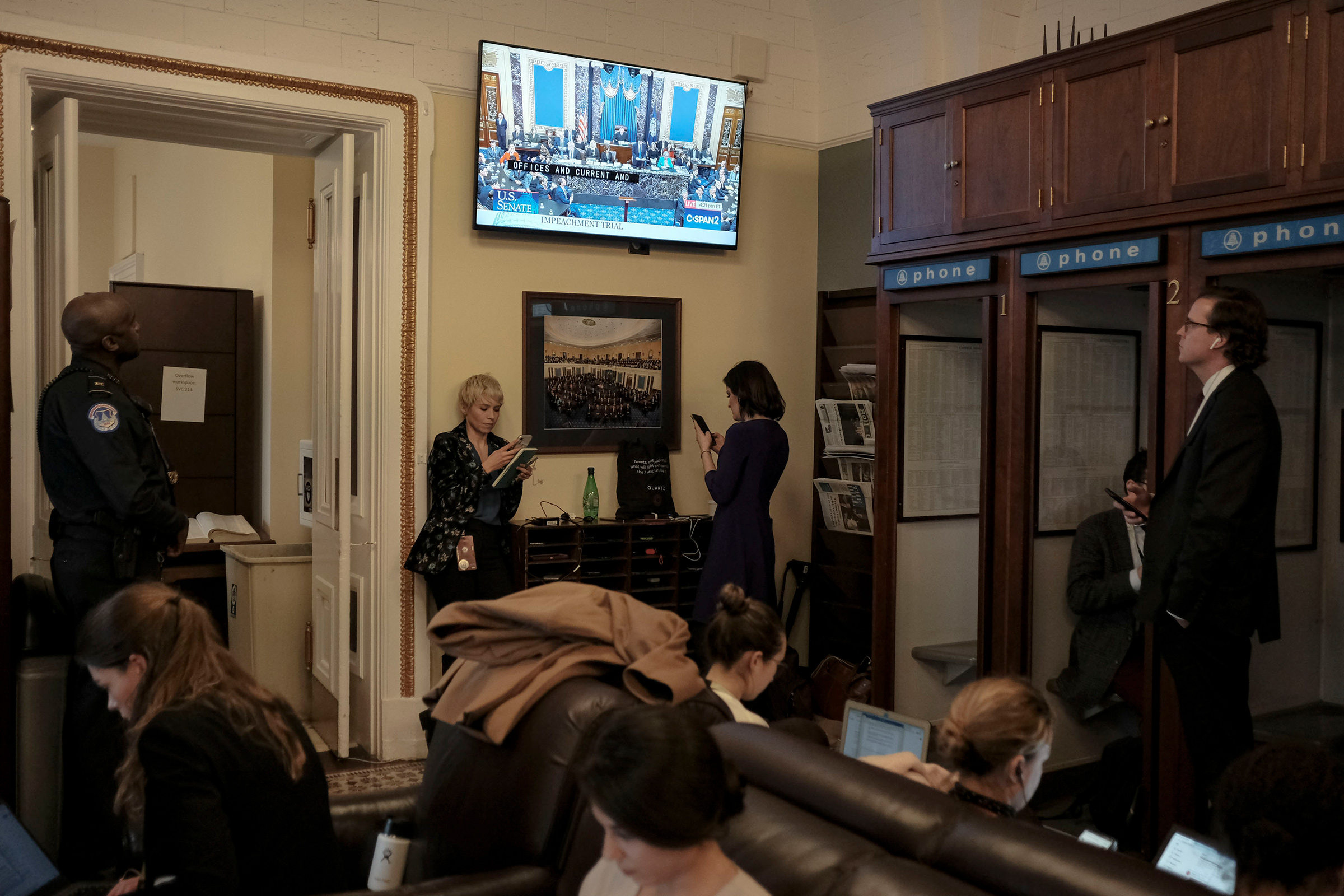

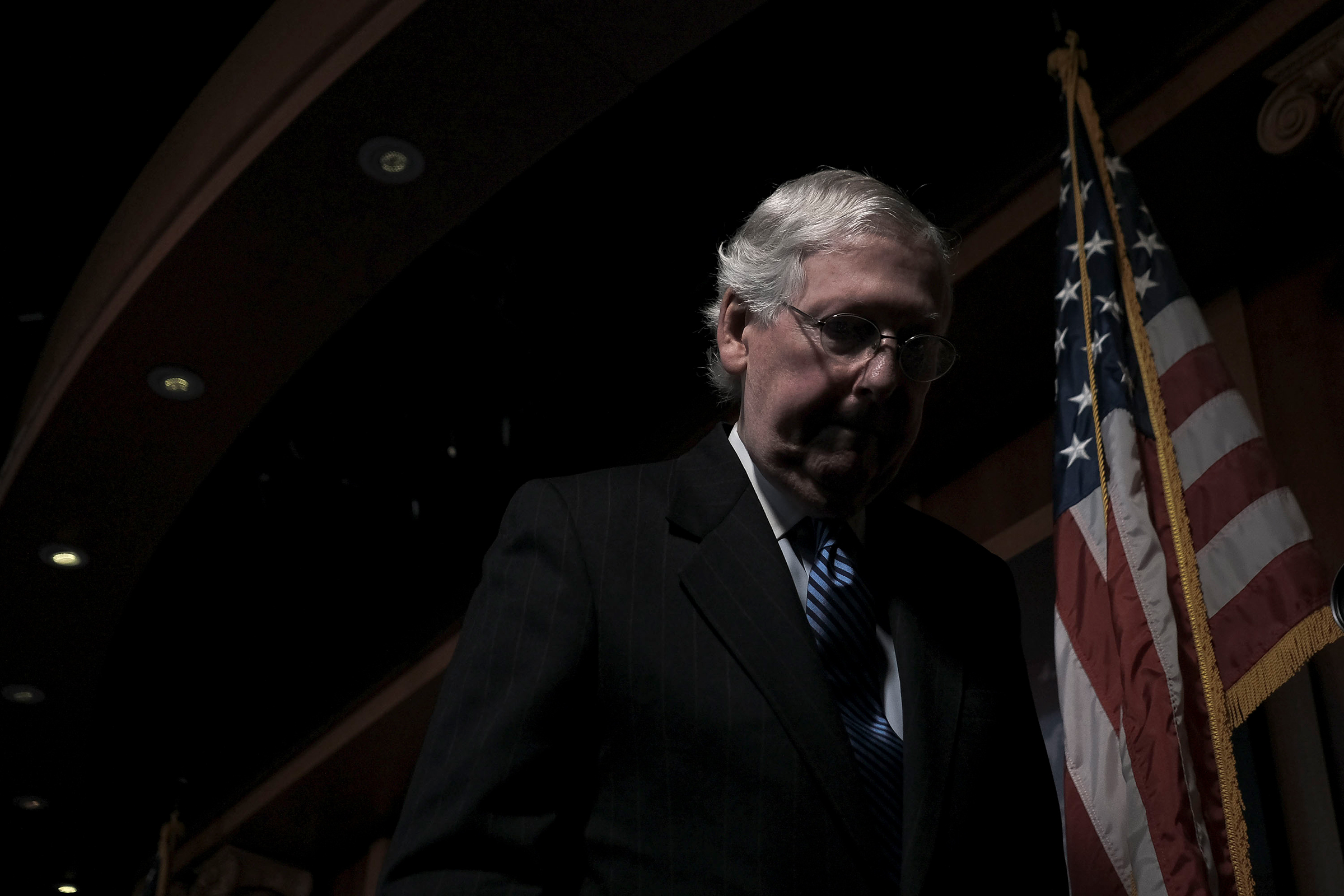

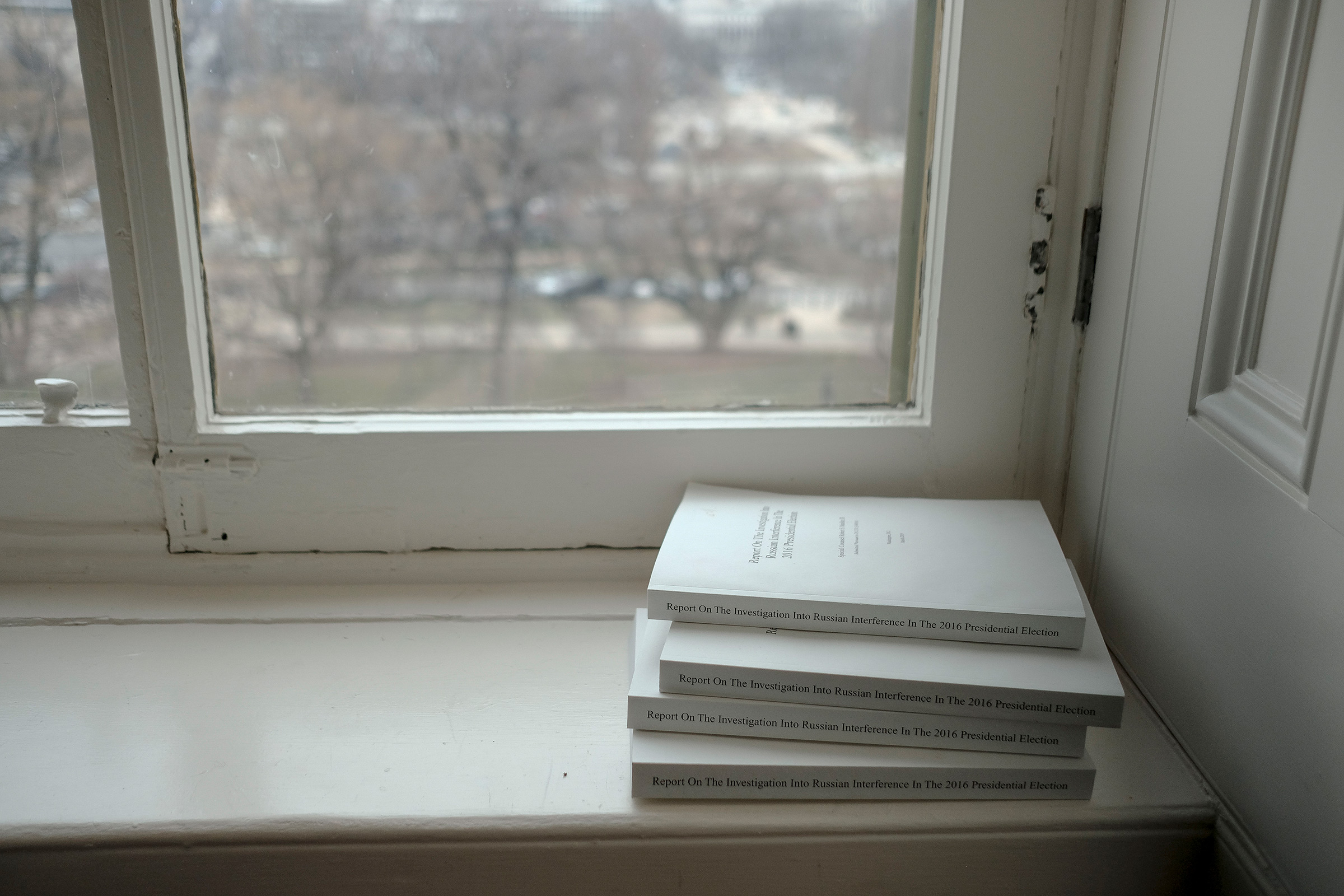

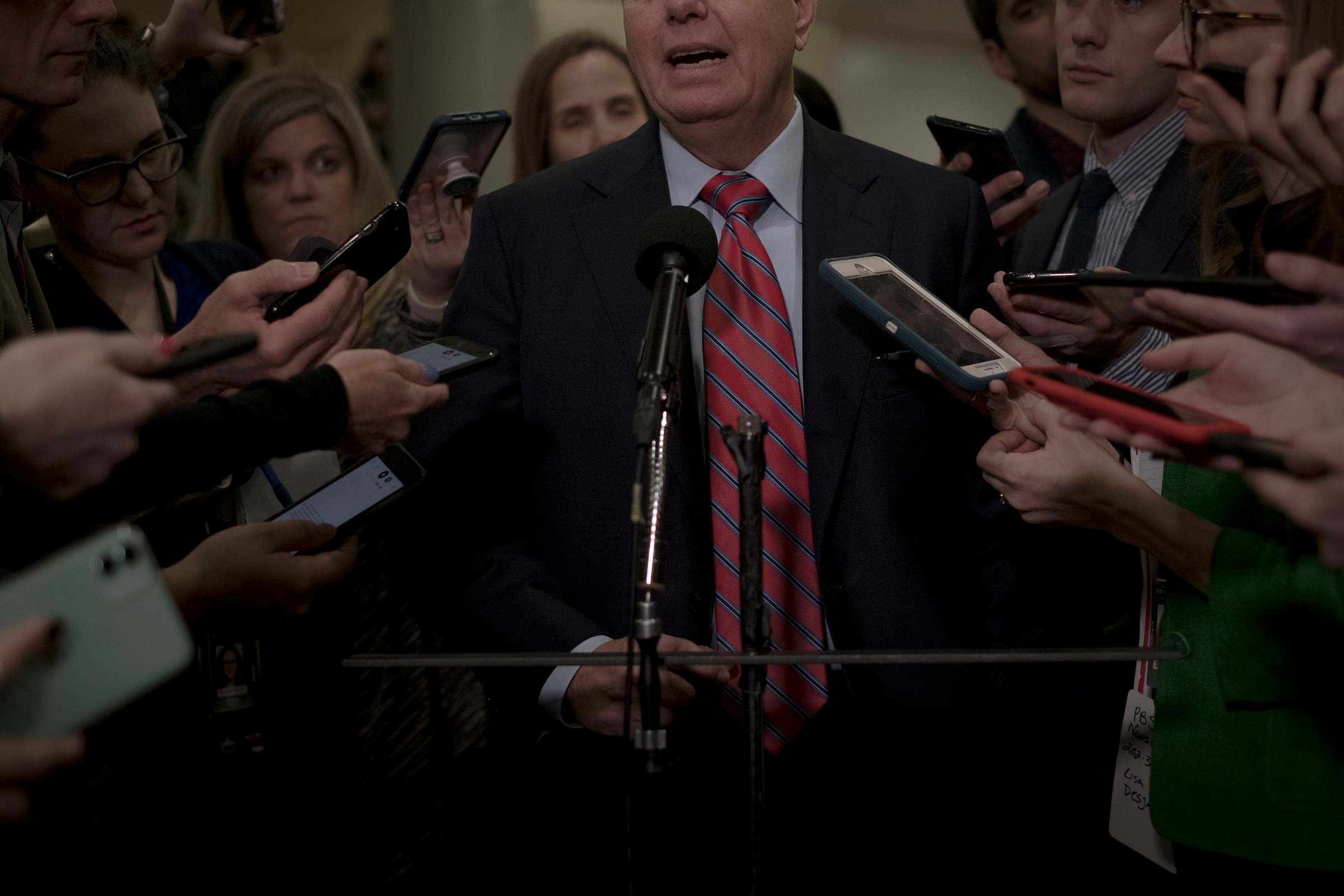

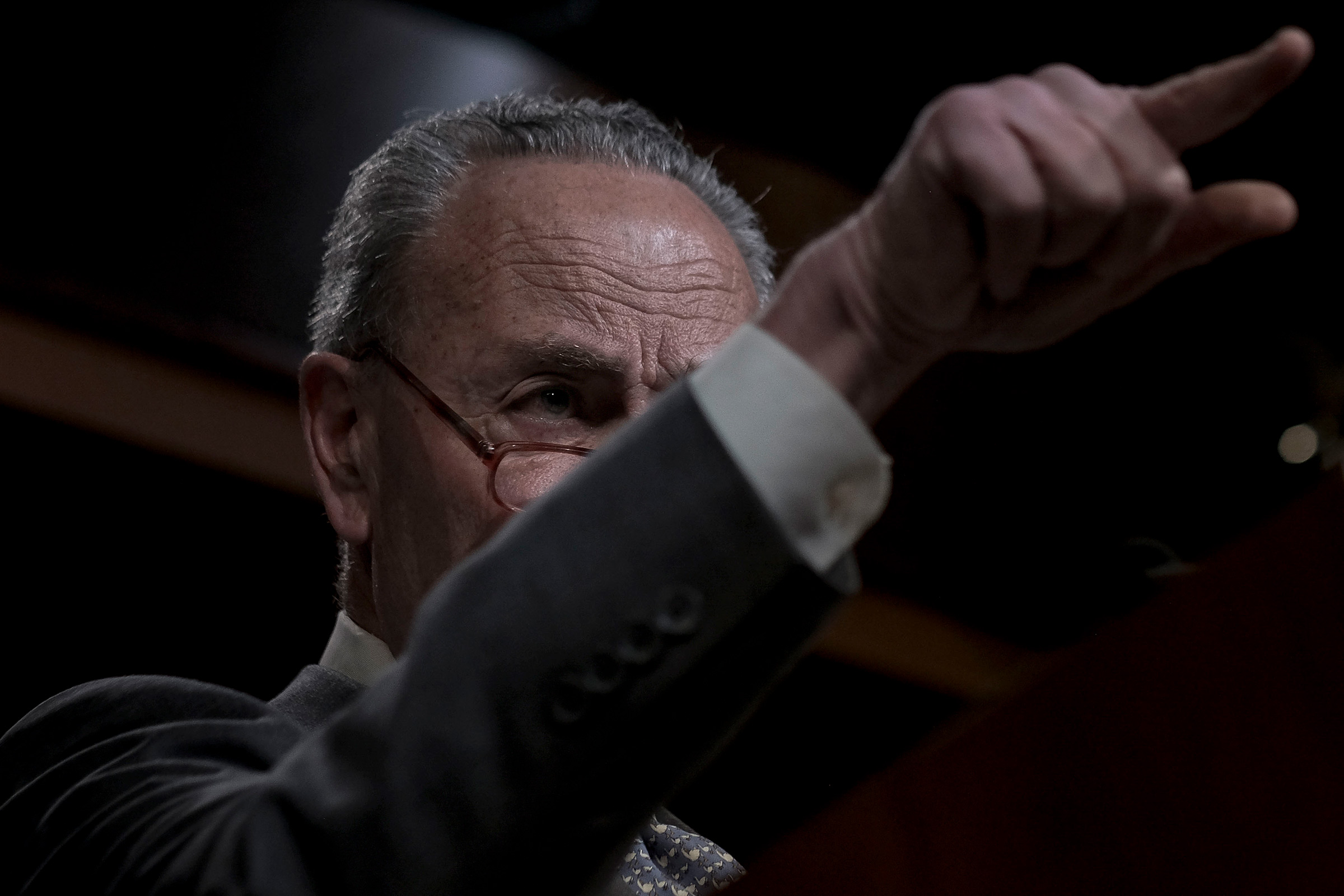

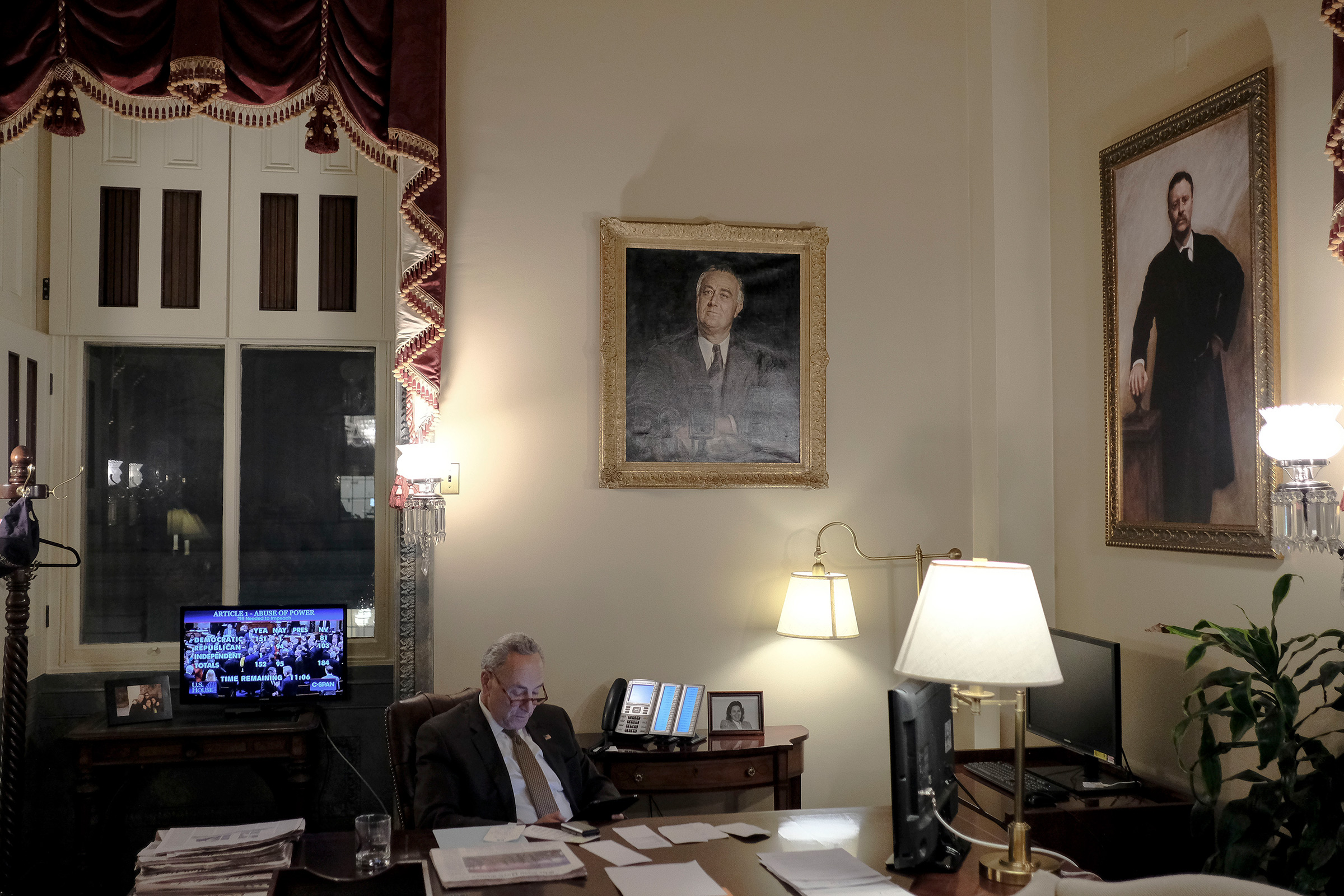

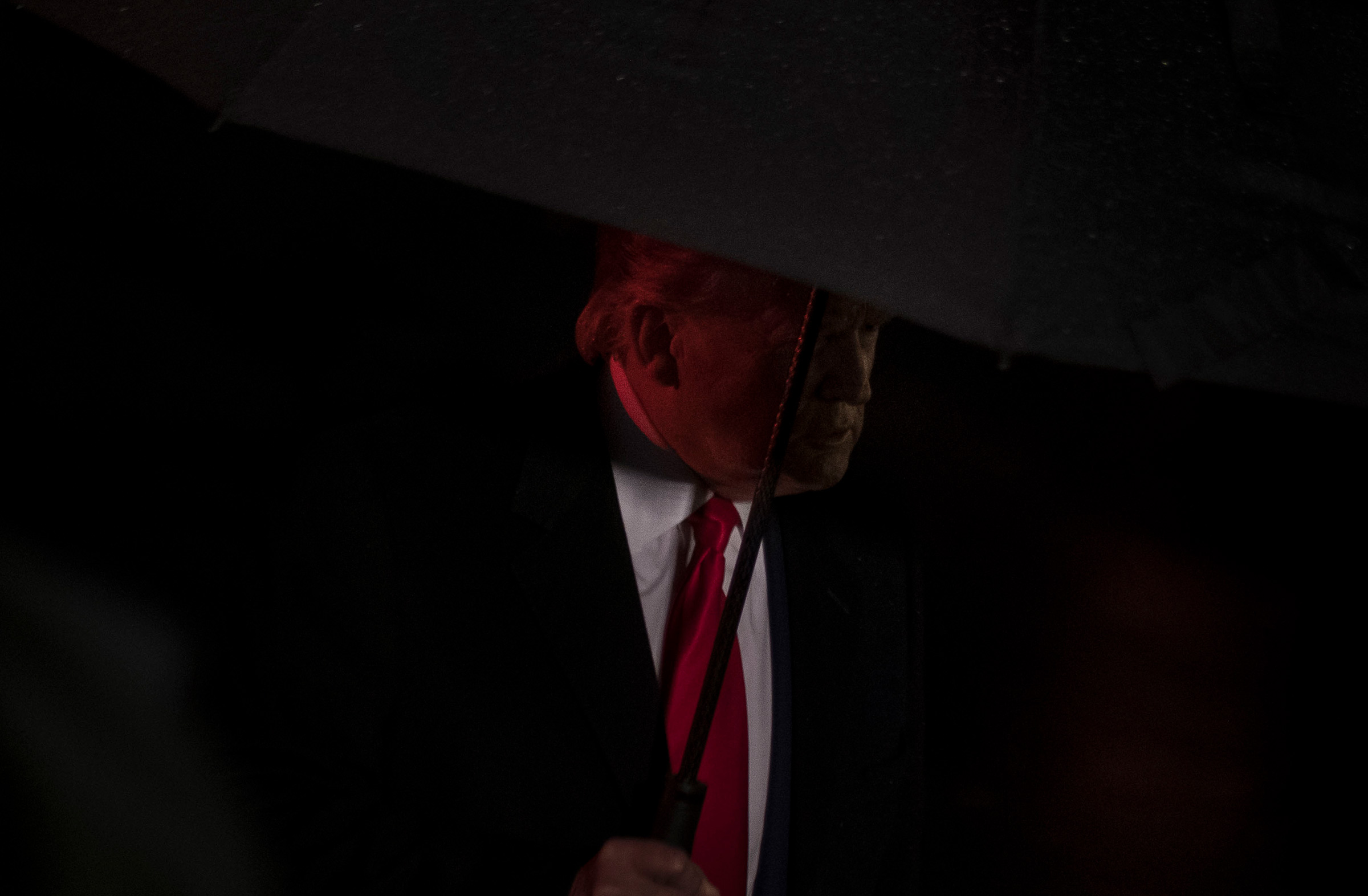

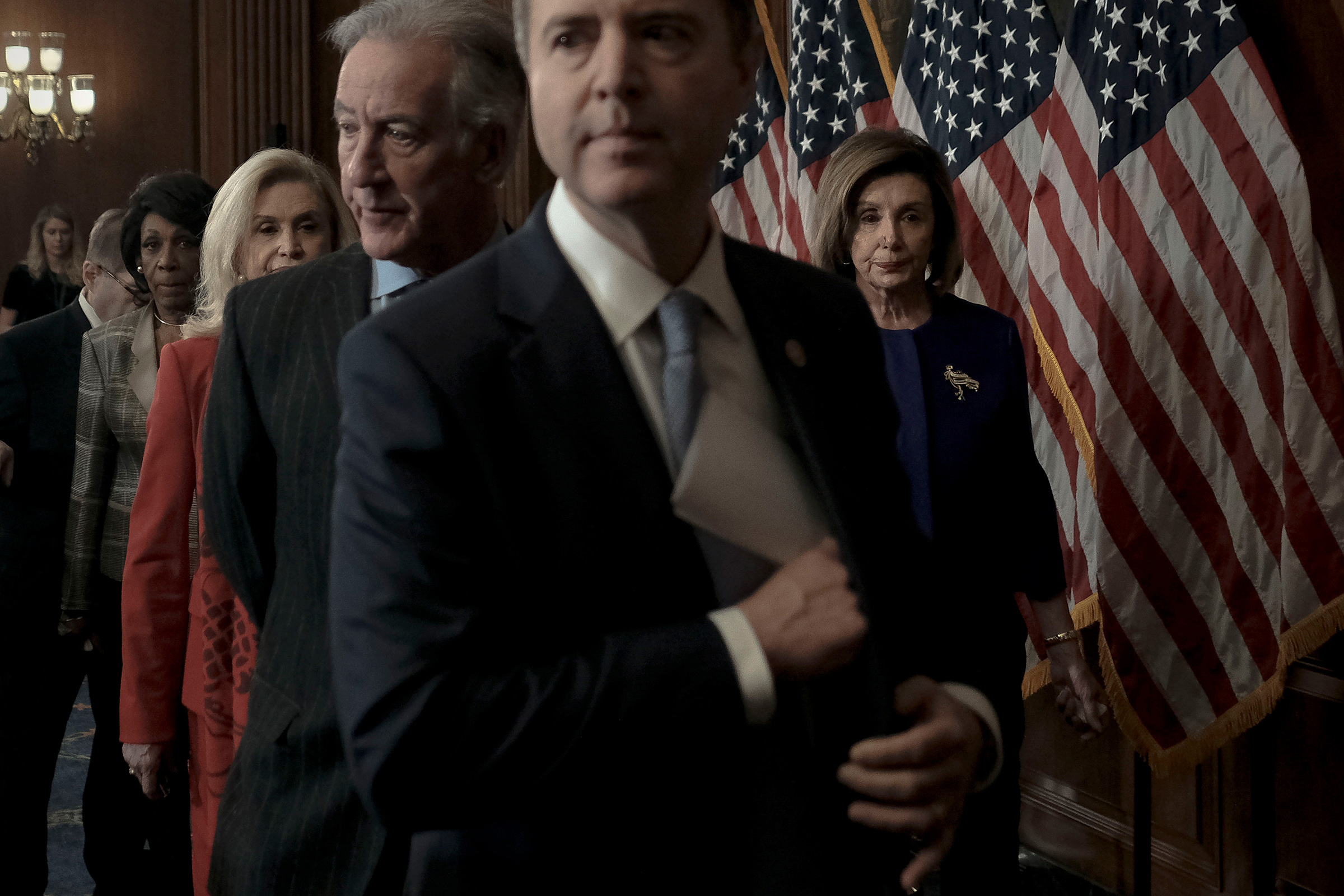

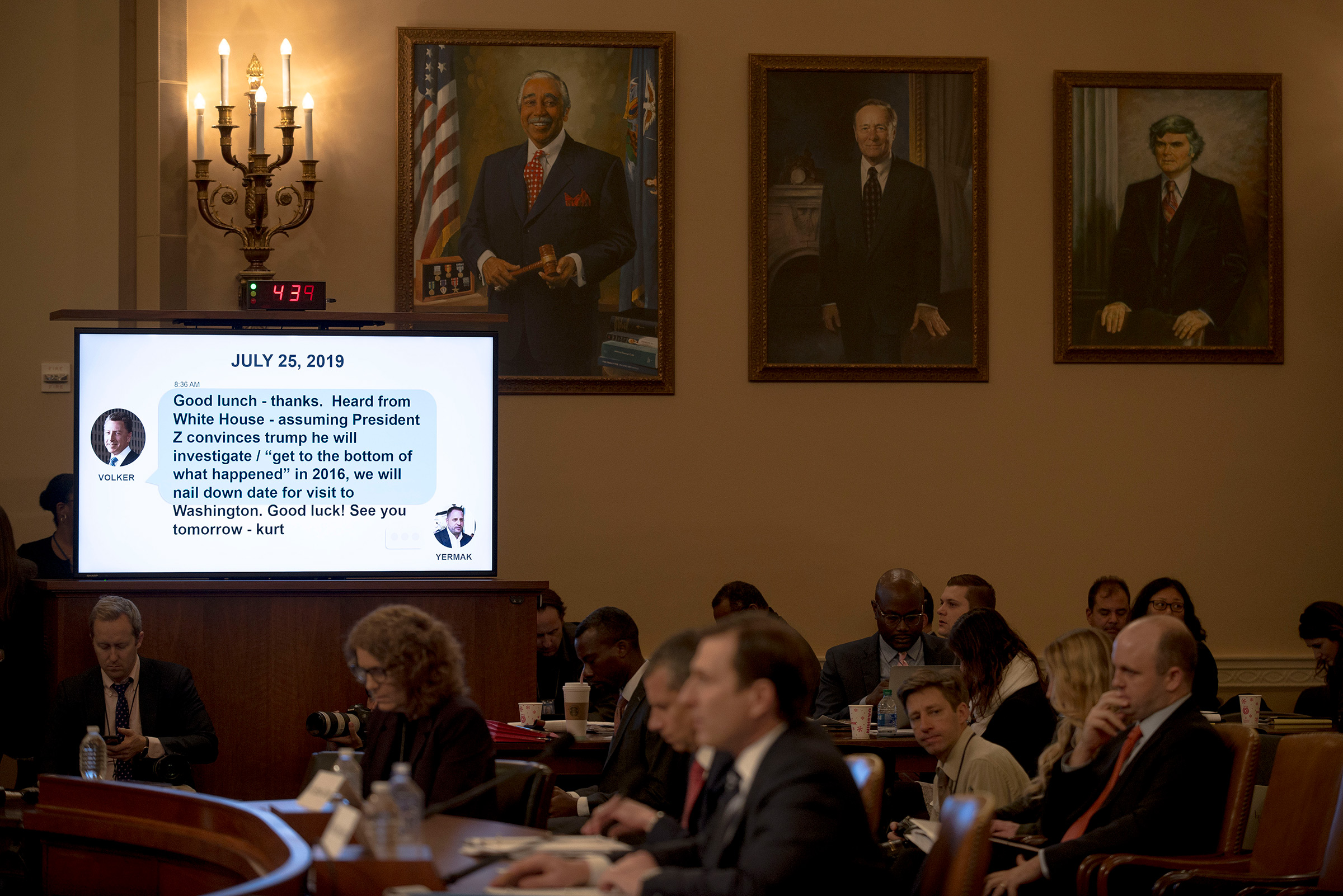

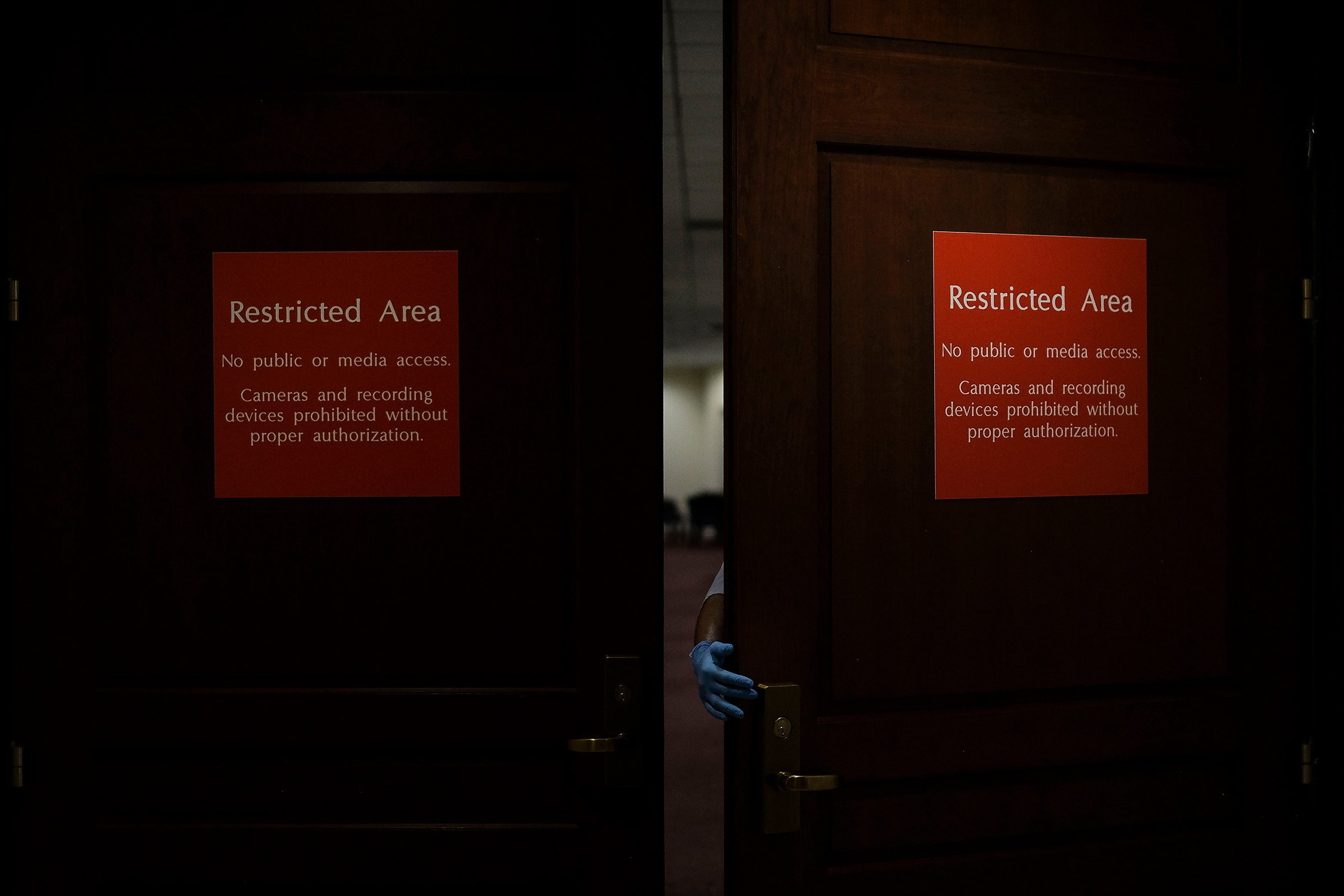

Since September 2019, photographer Gabriella Demczuk has been documenting this historic impeachment for TIME.

Correction, Feb. 6

The original version of this story misstated how Senator Lisa Murkowski voted on the articles of impeachment. She voted to acquit President Trump, not convict.

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders