Joker is shaping up to be the most controversial movie of the year. The film was received rapturously at the Venice Film Festival and broke the October opening weekend box-office record with an estimated $93.5 million. But it also has some critics worried about how moviegoers will interpret the story of a man struggling with mental health issues who is pushed to violence — and at least one “credible” mass shooting threat was made, according to military officials.

Maybe we shouldn’t be surprised that the latest version of the Joker is courting controversy. After all, he’s been doing so for decades. Creators and performers have pushed boundaries with the character, like when he committed a sexually violent act in the 1988 graphic novel The Killing Joke, or when Jared Leto got into character on the set of Suicide Squad by sending his cast mates used condoms. Between these transgressive acts and his overall inclination toward nihilism and anarchy, the Joker has become a potent symbol on the internet for many people who feel isolated from or angry at society. Heath Ledger’s iconic take on the character in The Dark Knight (2008), in particular, has been memeified by anarchists, gamer-gaters, men’s rights activists and incels, his ethos of “let the world burn” inspiring trolls across social media.

The lawlessness of the internet makes it a place where any character or symbol can easily be spun out of control or coopted by people with ill intent. Just look at Pepe the Frog, a goofy stoned cartoon amphibian that evolved into a symbol of hatred favored by the alt-right, despite the fact that its creator says he was meant to represent love. Men’s Rights Activists radically misinterpreted The Matrix’s “red pill” (the pill that shows Neo the truth, that he lives in a manufactured Matrix) to describe the supposed “lies” of feminism. Since then, that movie’s writer-directors, Lana and Lilly Wachowski, have come out as trans women, and the red pill choice has commonly been read as a metaphor for the trans experience, to the chagrin of some transphobic men’s rights activists.

The Joker’s long history of being misinterpreted as a heroic figure, rather than a terrorist, has only added fuel to the debate over whether Joker’s particularly violent version of the character is worthy of the screen—especially given that director Todd Phillips tried to ground the movie in a reality that mirrors our own, rather than some artificial comic-book universe. The discussion around Joker centers on whether the movie scrutinizes or empathizes with its protagonist, whose acts of violence are born at least in part from feelings of rejection by women in his life. That particular aspect of the Joker’s personality parallels news stories we’ve heard about mass shooters who begin their killing spree with an act of domestic violence. Some critics have defended the movie’s dive into the inner life of such a villain as a way to better understand what drives these people to violence. Others worry that the script does not do enough to make clear that the Joker’s acts of terrorism are evil, not heroic.

Phillips and star Joaquin Phoenix were asked multiple times, while doing press for the movie, whether they are concerned about the film’s potential to be misinterpreted or inspire violence. Phillips has rejected this notion, telling the Associated Press, “I just hope people see it and take it as a movie.” He later doubled down, saying at the New York Film Festival that he thought it was not irresponsible, but rather “very responsible” to “take away the cartoon element of violence that we’ve become so immune to.” Phoenix reportedly walked out of an interview when asked about the possibility that the film might inspire a violent act. But none of their public statements have directly addressed the Joker’s history as a toxic touchpoint, from pre-internet days to the present moment.

To understand why the new Joker is so divisive, it’s important to look back at both the history of the villain and his rise to prominence in the darker corners of social media. Here’s how we reached this particular moment.

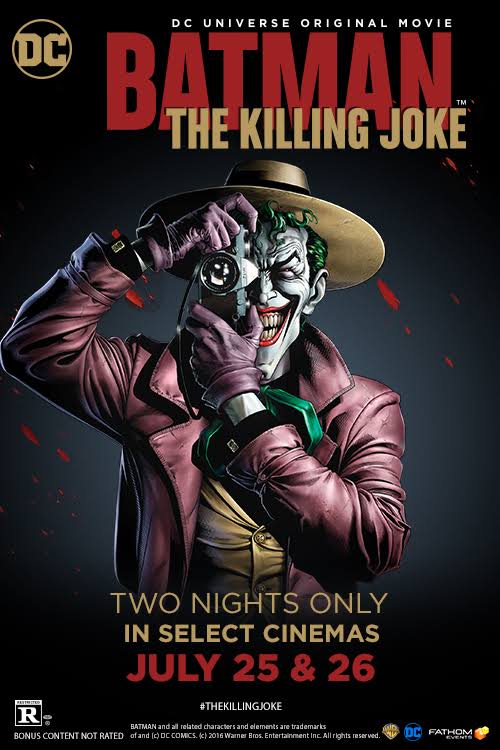

The Killing Joke (1988 book, 2016 movie)

The 1988 graphic novel The Killing Joke, written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Brian Bolland and John Higgins, offers what many comic-book fans call the definitive origin story of the Joker. We see in flashbacks that the Joker had a wife and family before he was driven to madness. In the present-day, the Joker breaks out of Arkham Asylum and tortures Commissioner Gordon in an effort to prove that even the noblest people can be pushed to evil and madness, just as he was.

In order to taunt Gordon, Joker shoots and paralyzes Gordon’s daughter Barbara, ending her career as Batgirl. He then strips her down and takes naked pictures of her to show to her father.

Feminists have critiqued the story for using Barbara as a plot device to motivate her father and Batman. The sexually explicit way in which Barbara is stripped of her power is particularly disturbing since such torture and humiliation is rarely imparted on male comic-book characters. Years after he wrote the comic, Moore said he regretted writing it: “I don’t even think it’s a good book.”

Controversy over the tale arose again when DC Entertainment adapted The Killing Joke into an R-rated animated film in 2016. The filmmakers conceded in interviews that Barbara had been a plot device in the original story. Unfortunately, they decided to boost her profile in the movie by turning Barbara into Batman’s love interest. The two characters had a father-daughter dynamic in the comics, but in The Killing Joke movie, Bruce Wayne and Barbara Gordon have sex on a rooftop before Barbara is maimed and abused by the Joker.

The new plot point only exacerbates the problematic portrayal of Barbara as a sexual object. Further, a new line written just for the movie implies that Joker also rapes Barbara in addition to taking naked pictures of her.

This portrayal of the Joker as a sexually exploitative character — and the ensuing feminist backlash against the storyline — only added fuel to the fire of the online debate about portrayals of women onscreen, with a small group of fans complaining that “Social Justice Warriors” and feminists were trying to censor The Killing Joke.

Batman (1989)

One year after The Killing Joke was published, Jack Nicholson portrayed the hateful harlequin in Tim Burton’s Batman. His interpretation inched even further from Cesar Romero’s campy portrayal in the 1960s Batman TV show, and closer to the ever-darker versions that haunt our screens today.

Nicholson was a brilliant choice for the role, given his talent for expressing eerily manic behavior in movies like The Shining. He played Joker as a man whose brain has gone haywire. That evolution, alone, stirred some controversy among critics. “There was something off-putting about the anger beneath the movie’s violence,” film critic Roger Ebert wrote in a mixed review. “This is a hostile, mean-spirited movie about ugly, evil people, and it doesn’t generate the liberating euphoria of the Superman or Indiana Jones pictures. It’s classified PG-13, but it’s not for kids.”

Decades later, Nicholson’s Joker is largely remembered as an icon in the superhero movie genre, offering a more serious and realistic take on the villain. For better or worse, it is this portrayal that set the template for the versions to come.

The Dark Knight (2008)

The Dark Knight offered the world a particularly disturbing version of the Joker that rightfully won Heath Ledger a posthumous Oscar the following year. Ledger’s Joker was a terrifying presence exactly because he refused to disclose his origin story. Throughout the movie, he offers different explanations for his facial scarring: in one story, the character runs a blade through his mouth to cheer up his disfigured wife; in another, an abusive father takes a blade to the Joker’s face. Toward the end of the film, the Joker begins to tell a third version when Batman interrupts him and throws him off a ledge. The Joker, like a terrorist, is trying to seed confusion and chaos. His enemies cannot study him or his motivations, nor predict what he is going to do. In 2008, he was a potent metaphor for the post-9/11 terrorist threat that the United States faced.

But the Joker’s unknowable nature also mirrored and presaged a toxic movement that would grow over the next decade. A certain contingent of fans embraced his brand of anarchy during a time of economic upheaval, rather than regarding the Joker as a threat to the nation.

In The Dark Knight, Alfred says, “Some men just want to watch the world burn” as a warning, but trolls took it up as a slogan. They created Joker-ized versions of Shepard Fairey’s famous “Hope” poster of Barack Obama. They interrupted debates over social, political and economic issues on Twitter with the Joker one-liner: “Why so serious?” There’s even a popular fan theory that the Joker is the hero of Dark Knight because he cleaned up Gotham’s streets.

The Joker is arguably the original troll, constantly undermining authority figures (Batman, Harvey Dent) and making light of others’ pain — seemingly impervious to retaliation exactly because he was as unknowable as an anonymous Twitter egg. In that role, he’s become omnipresent on social media. Based on his Twitter presence, the Joker seems to have left Gotham behind in favor of expressing so-called anti-Social Justice Warrior (SJW) views about how society has become too politically correct, whether that means adding empowered female characters to video games or favoring women in custody battles in court.

Suicide Squad (2016)

When Warner Bros. announced that Jared Leto would be playing the Joker in Suicide Squad, many fans were skeptical: After Ledger’s game-changing, Oscar-winning performance, how could a new version possibly live up to The Dark Knight villain?

Leto reportedly went full method for the role, sending used condoms and live rats to castmates including Will Smith on set. It was maybe all for naught: the Joker was largely cut out of the already haphazardly edited film.

The few scenes that did make the final cut focus on the Joker’s relationship with Harley Quinn. Their relationship is abusive: The Joker manipulates her when she’s his doctor and convinces her to harm herself physically to prove his love. Later, he murders a man who tries to flirt with her. Footage of the Joker knocking out Harley Quinn leaked before the film’s release and was met with much criticism. These scenes did not appear in the final cut.

Director David Ayer has defended the original script as a journey of independence and empowerment for Harley, who eventually rejects the Joker. We’ll never know how sensitive or nuanced a portrayal of a toxic relationship Ayer would have produced. For better or worse, the Joker being largely cut out of the film helped to maintain his status as a mysterious onscreen figure. His motivations — besides his unhealthy obsession with Harley — go largely unexplained. If he’s not as scary as Ledger’s Joker, at least he’s as aloof.

The Joker (2019)

Like The Killing Joke before it, Joker tries to explain the enigmatic villain. He has mental health issues. He can’t get the medication to help with those issues because of state cutbacks. He is treated poorly by people around him because of these issues. He feels abandoned by a father he never knew, infatuated with the mother who stayed. He stalks a woman and feels rejected by her. He’s bullied by the sorts of men who do get women’s attention because they have money and power. Eventually, he gets his hands on a gun and wreaks havoc.

A lot has changed in the decade since The Dark Knight premiered, including the kinds of threats Americans fear most. Home-grown terrorism has become an epidemic, with mass shootings carried out by disgruntled young men, often misogynists and domestic abusers with a history of violence toward women. The audience of Joker, it appears, is either supposed to empathize with a disillusioned shooter or at least understand why he committed acts of violence.

Now that mass audiences finally have a chance to see the film, after more than a month of critical debate online, they can decide for themselves how far to extend their empathy. Controversy clearly hasn’t deterred moviegoers — in fact, it may well have piqued their interest. Phoenix’s name is regularly dropped in early conversations about Oscar contenders, so we can expect debates about both his performance and the film’s worth as a piece of art to continue for months to come. But when those discussions eventually ebb, it’s safe to bet we’ll get another Joker down the line to get them raging again.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com