Twenty-seven years ago, two films depicting the Black Panther Party were released 10 months apart. The first, Forrest Gump, needed only two minutes to reduce the movement to nameless, arrogant militants in allegiance with a domestic abuser. The film won Best Picture at the Oscars, earned $680 million and became part of many high school history curriculums.

The second film, Mario Van Peebles’ Panther, portrayed the group as a grassroots organization of idealists systematically stifled and imprisoned by an unjust legal system. The film drew vicious attacks from conservatives and skepticism from critics, with one Baltimore Sun story citing detractors who linked its antigovernment ideology to that behind the recent Oklahoma City bombing. Panther took in $6.8 million before fading from view; it’s currently unavailable on any streaming platform.

Those two films and their fates can be read as an object lesson in Hollywood’s relationship with Black history. While cinema has long had a love affair with historical narratives—reverently re-creating the lives of scientists, gangsters, pilots and kings—very few of those figures have been Black. In movies about the civil rights era like The Help and Mississippi Burning, Black activists are sidelined in favor of white do-gooder protagonists. Elsewhere, Black figures are thrust into a few reductive tracks: “a slave, a butler or some street hood,” as the character Jesse sums up in Robert Townsend’s 1987 satire, Hollywood Shuffle. Black filmmakers who attempted to reframe Black history in projects like Malcolm X, Panther and Rosewood described overcoming years of stony industry resistance to put those movies in front of audiences.

Over the past few years, however, a growing number of Black filmmakers have found opportunities to tell history-based stories, determined to reject white-savior narratives and center Black interiority. They have grieved anew alongside the Central Park Five (When They See Us) and taught many about the buried history of the Tulsa race massacre (Watchmen). They’ve instilled compassion and unruly texture into stories of 1980s drag ball performers (Pose); a titan of the blues (Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom); and the first Black female presidential candidate for a major party, Shirley Chisholm (Mrs. America)—celebrating not just greatness or injustice but also parts of Black life that had previously unfolded offscreen.

These works are not just a matter of representation but of history itself. Research has shown that powerful narrative can subsume previous memories; films can indelibly shape public understanding of historical events. “There’s a responsibility to understand that if you do your job right and enter the public consciousness, you will have overwritten actual history with your own imagination,” Trey Ellis, a filmmaker and film professor at Columbia University, says.

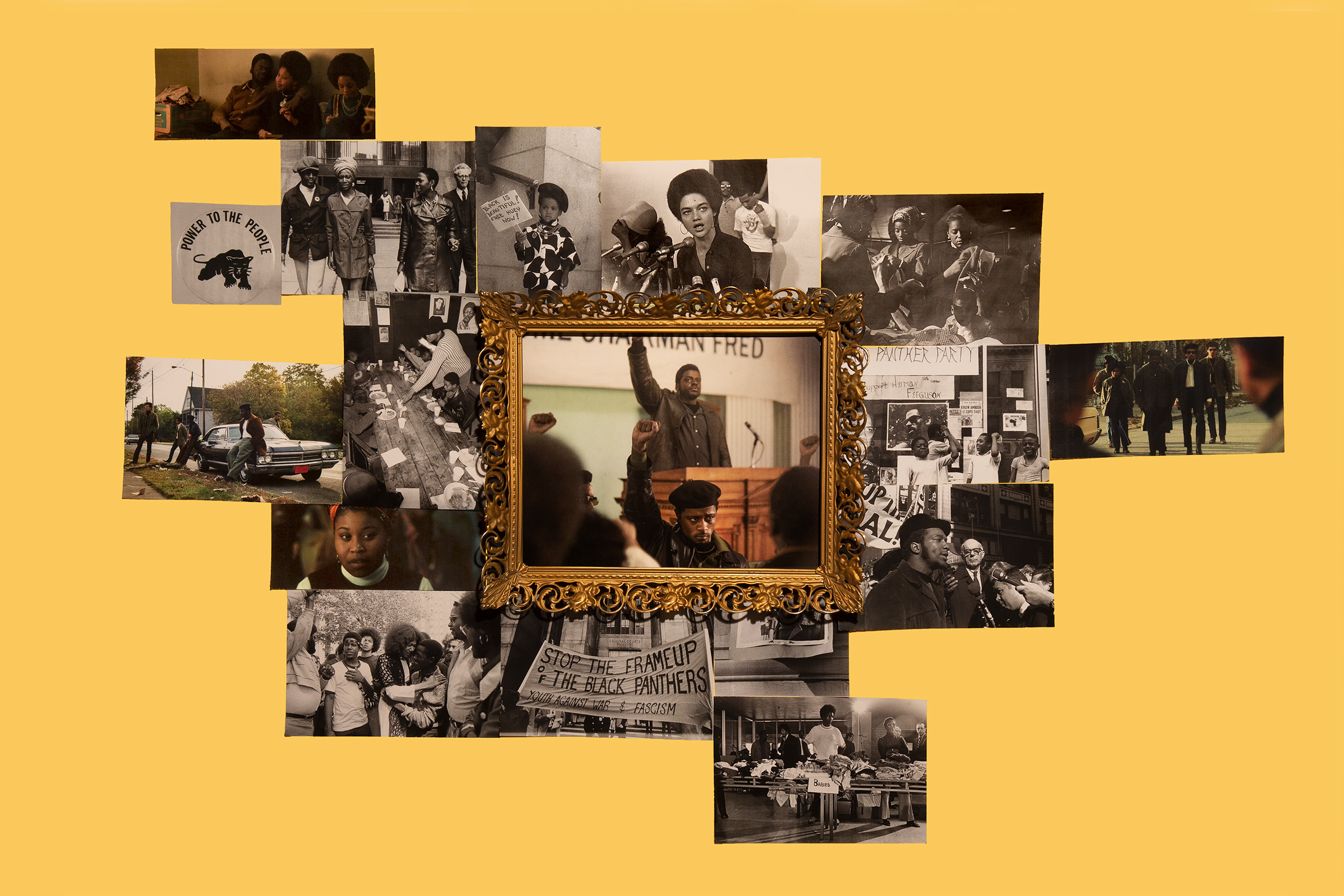

This month, the Black Panthers will get a new appraisal in Shaka King’s Judas and the Black Messiah, which is already receiving acclaim and Oscar buzz far more in line with Forrest Gump than Panther. The film, which hits theaters and HBO Max on Feb. 12, portrays Chicago Panthers, including charismatic leader Fred Hampton (Daniel Kaluuya), not as cold-blooded vigilantes but as community organizers with ideological rigor and deep interpersonal bonds, while the FBI embarks on a ruthless quest to silence them—even if that requires putting bullets in their sleeping bodies.

The challenge for King and other Black creators is providing both remedial education and speaking to a present still rife with prejudice. “I’m not trying to erase what’s there, because that will never be accomplished in my lifetime. This is generations of oppressive, calculated misinformation,” Ava DuVernay (When They See Us, Selma) says. “But I can assert truth and fact and say, ‘This is information that is missing from that narrative. This is a point of view that was never considered.’”

America’s miseducation in Black history starts in school systems and the media. A 2014 report by the Southern Poverty Law Center gave D’s and F’s to the majority of states’ approaches to teaching the civil rights movement, with five states neglecting the subject altogether. Black history lessons often focus on slavery and even then can downplay the atrocity of the slave trade: five years ago, a ninth-grade geography textbook made headlines for describing enslaved Africans as “workers.” Figures like Ida B. Wells and James Baldwin are chronically undertaught. Some editions of the textbook The American Pageant, which has been used for decades in AP History classes, reduced the Black Panthers to two sentences: “With frightening frequency, violence or the threat of violence raised its head in the black community. The Black Panther party openly brandished weapons in the streets of Oakland, California.”

Hollywood, with its primacy in the American imagination, has played a significant role in upholding a certain vision of American history; indeed, that impulse is baked into its origins. The first American blockbuster, D.W. Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation, portrays African Americans—played by white actors in blackface—as predators or simpletons unfit for freedom, and the Ku Klux Klan as saviors of the antebellum South. The movie was instrumental to the Klan’s revival and the flourishing of Jim Crow laws.

Over the following decades, mainstream films like Song of the South, Gone With the Wind and the Shirley Temple–starring The Littlest Rebel would confer nostalgia upon plantation life and portray the enslaved as grateful to their protective owners. Later, when white filmmakers tackled America’s original sin or the civil rights movement, they often made Black characters ancillary to rousing white allies (Amistad, Glory); white audiences left the theater with no inkling of complicity in racist structures. “We’ve been treated as objects as opposed to subjects,” Ellis says. “Even in the well-intentioned, liberal movies in the ’80s and ’90s, Hollywood just couldn’t get its head wrapped around the Black experience.”

In a lily-white industry, a few Black filmmakers, including Spike Lee and John Singleton, were able to break through and portray Black stories with richness and depth. But attempting to expose more shameful parts of American history proved difficult. Lee’s Malcolm X, released in 1992, was saved financially only after he solicited prominent Black donors like Michael Jordan and Oprah Winfrey. Singleton said that Rosewood (1997), which recounted the 1923 massacre of a predominantly Black Florida town at the hands of a white mob, received scant studio support, which contributed to its commercial failure.

Also in the ’90s, New Jack City filmmaker Van Peebles began shopping around a script for a movie that cast the Black Panthers in a new light. He knew history books and mainstream media had reduced them to their militance, and he wanted to highlight their efforts to feed and protect their communities and combat police brutality—and their treatment by the FBI. But Van Peebles couldn’t get studios to greenlight a project with a significant budget.

“One studio executive said, ‘I dig the script; I was a radical and love the Panthers. But we have to make the lead character white,’” he recalls. The executive suggested casting “a Bridget Fonda type” who teaches a group of Black men to read, leading to their becoming the Black Panthers. Van Peebles eventually got to make Panther the way he wanted, for $9 million. It failed to recoup its costs.

Recent structural changes in Hollywood have led to more Black creators’ getting their own platforms to tell Black stories. The Black Lives Matter and #OscarsSoWhite movements put pressure on white gatekeepers, while box-office successes like Moonlight, Get Out and especially the Marvel epic Black Panther showed that Black stories of all stripes could draw audiences. The advent of streaming has widened the conception of what an “average” theatergoer looks like. And Black executives, like Warner Bros.’ Channing Dungey, finally started to get promoted into decision-making positions. The result has been a flurry of Black stories across genres, from romance (If Beale Street Could Talk) to horror (Us) to comedy (Girls Trip).

Given Hollywood’s obsession with true stories, it’s not surprising that Black creators would use these opportunities to reclaim forgotten chapters of history. These films and TV shows serve both as validation for Black audiences—who have long had to protect their stories themselves—and as civic lessons for those less informed. And these projects have already started to make an impact on the nation’s collective memory. DuVernay’s 13th, for example, has been added to high school and college curriculums for its incisive exploration of mass incarceration’s ties to slavery. Her series When They See Us was Netflix’s most watched series in the U.S. every day for two weeks upon its release—and led to Central Park Five prosecutor Linda Fairstein’s being dropped by her publisher and resigning from the board of Vassar College amid public outrage.

“For years, our stories have been told and commodified in a way that reduced us in other people’s eyes and in our own eyes,” When They See Us screenwriter Julian Breece says. “It’s important for us to rescue our narrative—because that’s what rescues our humanity.”

In 2019, after its depiction in HBO’s Watchmen, a flurry of research and writing emerged online about the Tulsa race massacre—when an officially sanctioned white mob attacked a flourishing Black Tulsa neighborhood in 1921, killing possibly hundreds and destroying its entire business district. Showrunner Damon Lindelof (Lost) had the idea to tell the story after reading about it in Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “The Case for Reparations”—and brought it to life with a majority-Black writers’ room to shape the narrative. The massacre is rarely taught in schools: show writer Christal Henry says she didn’t learn about it until college and was deluged with incredulous messages after the show aired. “I got responses from white friends, like, ‘This is crazy. I thought you made it up,’” she says.

Watchmen was HBO’s most watched new show of 2019. Since then, there has been a heightened interest in new developments related to the massacre, including the discovery of a mass grave that likely holds its victims and Human Rights Watch’s demands for reparations for survivors and descendants. “This is the worst thing that’s ever happened in our city, and you had generations grow up here not knowing that it happened,” Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum says. “When you have a show with that much visibility shine a light all of a sudden, it’s incredibly powerful.”

Now it’s the Black Panthers’ turn for a mainstream reclamation. Negative connotations of the group—“reduced to leather peacoats and shotguns”—as Judas director King puts it, still linger, thanks to decades of fearful or sensationalist coverage. In 2016, when Beyoncé performed at the Super Bowl with her dancers sporting Pantheresque black berets, the executive director of the National Sheriffs’ Association accused her of “inciting bad behavior.”

This reputation made it extremely difficult for Judas and the Black Messiah to get made. Forest Whitaker and Antoine Fuqua tried for years to kickstart a project; so did Warner Bros. executive Niija Kuykendall. A24 and Netflix passed on the initial pitch for Judas, created by the Lucas Brothers writing team. In the end, it took a massive effort from some of the biggest names in the business: producer Ryan Coogler, coming off the $1.3 billion-grossing Black Panther; powerhouse producer Charles D. King, who financed half the film himself; two newly bankable stars in Daniel Kaluuya and LaKeith Stanfield; and Kuykendall, who, as executive vice president of film production at Warner Bros., is one of the few Black women in a Hollywood executive role.

The filmmakers hope that Judas deepens the public perception of the Panthers, calling attention to free breakfast programs that fed thousands of children, free legal aid, health clinics, and peace-pact negotiations between Chicago gangs. Kaluuya, who plays Hampton in the film, is particularly excited to educate people about Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition, which united disenfranchised Hispanic, white and Black organizing groups in Chicago, flying in the face of the Panthers’ reputation as anti-white. “It showed me the importance of union and understanding where we share core values—and putting aside what they want us to fight over,” he says.

Crucially, the film documents FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s war against the Panthers, which for years was dismissed as conspiracy theory. Congressional investigators and others found that Hoover’s agents spread disinformation and dissent, planted informants, forged documents, harassed members and even, in the case of Hampton, assassinated them.

“There will be those who say the film is pro-Panther propaganda and that we’re making things up,” Shaka King says. “But they won’t have any evidence to support that.”

Other projects from Black creators will burrow even deeper into Black history in the years ahead. Questlove’s Summer of Soul unearths buried footage from the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival. Genius: Aretha and The United States vs. Billie Holiday re-examine two iconic and oft misunderstood musicians. When They See Us‘ Breece is writing a biopic of the legendary dancer Alvin Ailey, while Van Peebles has a follow-up to his groundbreaking 1993 Black cowboy film, Posse, reminding the world that 1 in 4 cowboys during the golden age of westward expansion was Black. “Kids want to be the success they see. They want to sit tall in the saddle,” he says.

King hopes that Hollywood, after exploring what he terms a “Black excellence industrial complex,” will enter into a “Black radical industrial complex,” championing stories that challenge the hegemonic narratives of America. He’s also hopeful that stories across ethnicities that have likewise been ignored by Hollywood will come to light. “When it comes to Hollywood and Latinos or Asians in the U.S., that history is completely absent too,” the director says. “I think that the possibilities are endless.”

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness