Jordan Neely’s death has been ruled a homicide, days after a white New York City subway rider held the 30-year-old Black man in a chokehold on a train on May 1. According to Juan Alberto Vazquez, a freelance journalist who shot a viral video of the encounter, Neely, a regular fixture on the subways as a Michael Jackson impersonator, had been screaming on the train, and may have been having some sort of mental breakdown.

For some, the footage felt sickeningly familiar. In a May 3 statement, civil rights activist Rev. Al Sharpton compared the incident to Bernhard Goetz, who shot four Black men on the subway on Dec. 22, 1984, saying he believed they were trying to rob him. “We cannot end up back to a place where vigilantism is tolerable,” Sharpton said. “It wasn’t acceptable then and it cannot be acceptable now.”

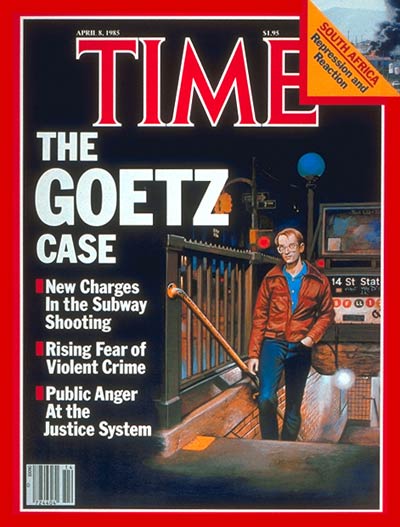

Here’s how TIME recounted the 1984 subway shooting in the Apr. 8, 1985, issue of the magazine:

The weather was unseasonably warm on the Saturday before Christmas when Goetz strolled out of his apartment. He descended into the 14th Street station of the Seventh Avenue subway line. As the No. 2 express screeched to a halt, Goetz, wearing a blue windbreaker, quickly scanned the cars, looking for a relatively empty one. According to his later statements, he took a seat across from the door through which he entered, on a long bench. Directly opposite him sat Troy Canty, 19; to Goetz’s right, on a short two-seat bench, sat Darrell Cabey, 19, and James Ramseur, 19. Diagonally across from Goetz sat Barry Allen, 18.

Canty asked Goetz how he was. Fine, Goetz replied. Anywhere else in the world that might seem like an innocuous exchange; on a Manhattan subway it can be ominous. According to Goetz, two of them, probably Canty and Allen, got up and moved to his left. Goetz knew that something was up. He also knew that he had a loaded gun tucked in his trousers. As Goetz recounts the incident, Canty then said, “Give me $5.” Canty’s attorney claims his client made a request, not a demand.

Goetz rose slowly, partly unzipping his jacket. He asked Canty what he had said. Canty repeated the statement. Goetz says that one of the others made a gesture indicating that he might have a weapon. Goetz later told police that by then he had mentally constructed his “field of fire.” Said Goetz: “I had no intention of killing them at that time, but then I saw the smile on his face and the shine in his eyes, that he was enjoying this. I knew what they were going to do. Do you understand?”

Goetz finished unzipping his jacket and pulled out the silver-colored gun. He assumed a combat stance, gripping the revolver with both hands, and shot Canty through the center of his body. He then turned slightly to his right and shot Allen, who had turned to flee, in the back; he fired again, wounding Ramseur in the arm and chest; he then fired a fourth time, a shot that may have missed, at Cabey. Said Victor Flores, 47, a transit authority employee who witnessed the mayhem: “The kids were frightened, backing off, trying to get away. There was no reason to shoot them. They fell one after another. Bang! Bang! Bang!” By his own account, Goetz then walked over to Cabey, who was sprawled on the seat, perhaps playing possum. “You seem to be doing all right,” Goetz said. “Here’s another.” That fifth and last bullet, one of two expanding dumdum slugs in the revolver, may have severed Cabey’s spinal cord, paralyzing him from the waist down. In one of the case’s many oddities, Flores disputes Goetz’s account of what happened with Cabey. “He didn’t shoot the kid a second time. He didn’t say anything either.”

Afterward, in a telephone conversation recorded by a neighbor and later printed in New York magazine, Goetz agitatedly explained how he felt at the time: “If you corner a rat and you are about to butcher it, O.K.? The way I responded was viciously and savagely, just like a rat.”…Goetz’s subsequent explanation was more explicit: “I know in my heart I was a murderer . . . I just snapped.”

Back then, there were a lot of questions about what exactly led Goetz to shoot the teens, and mental health experts told TIME to look at his troubled background. His father was convicted on charges of molesting two teen boys. Goetz himself was divorced. In 1981, he bought a pistol after being jumped by Black youths in the subway, but escaped, and mental health experts told the magazine that he may have shot at the boys in the subway four years later as an act of revenge. Goetz became an overnight celebrity, and TIME wrote that “the 37-year-old electrical engineer became a tabula rasa on which Americans etched their uneasiness and projected their fantasies of retaliation.”

Read More: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: America’s Dark Obsession With Vigilante Justice

In 1987, Goetz was acquitted on attempted murder, fined $5,000, and sentenced to six months in prison for illegal weapons possession and community service. At the time, Sharpton said Goetz got off easy because he was white, arguing, “If Bernie Goetz had been Black, he would have gotten much more than six months.”

Neely’s death also raises painful and complicated questions about crime and mental health. Some in rightwing circles have praised the subway rider who held Neely in a chokehold, believed to be a 24-year-old Marine veteran, and criticized crime rates in New York City. Others say the chokehold was an extreme reaction. Manhattan borough president Mark Levine tweeted, “Our broken mental health system failed him. He deserved help, not to die in a chokehold on the floor of the subway.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com