These are independent reviews of the products mentioned, but TIME receives a commission when purchases are made through affiliate links at no additional cost to the purchaser.

Years ago, I was in Amsterdam with one of my friends, Jen. We’d smoked pot that day. Try not to be upset about this. In Amsterdam, that’s what people have for breakfast with their Pannenkoeken.

While walking through the city, I tripped and fell for absolutely no reason. After I fell, I lay on the ground for a moment in shock. I wasn’t hurt or anything, I was just surprised. My shoes were tied, the pavement was smooth, and I hadn’t been wildly weaving or jumping around or even walking very quickly. And yes, I was a little high, but not in a way that would have led to forgetting how to walk. There was really no excuse at all for me not to be upright. I looked up from the ground and said, “Jen! Gah! What if, someday, I become one of those people who just falls for no reason?” We found this idea so outrageous, so hilarious (because, high), that we laughed and laughed. To me, lying there on the ground, barely into my early 30s, falling for no reason was something that happened only to much, much older people.

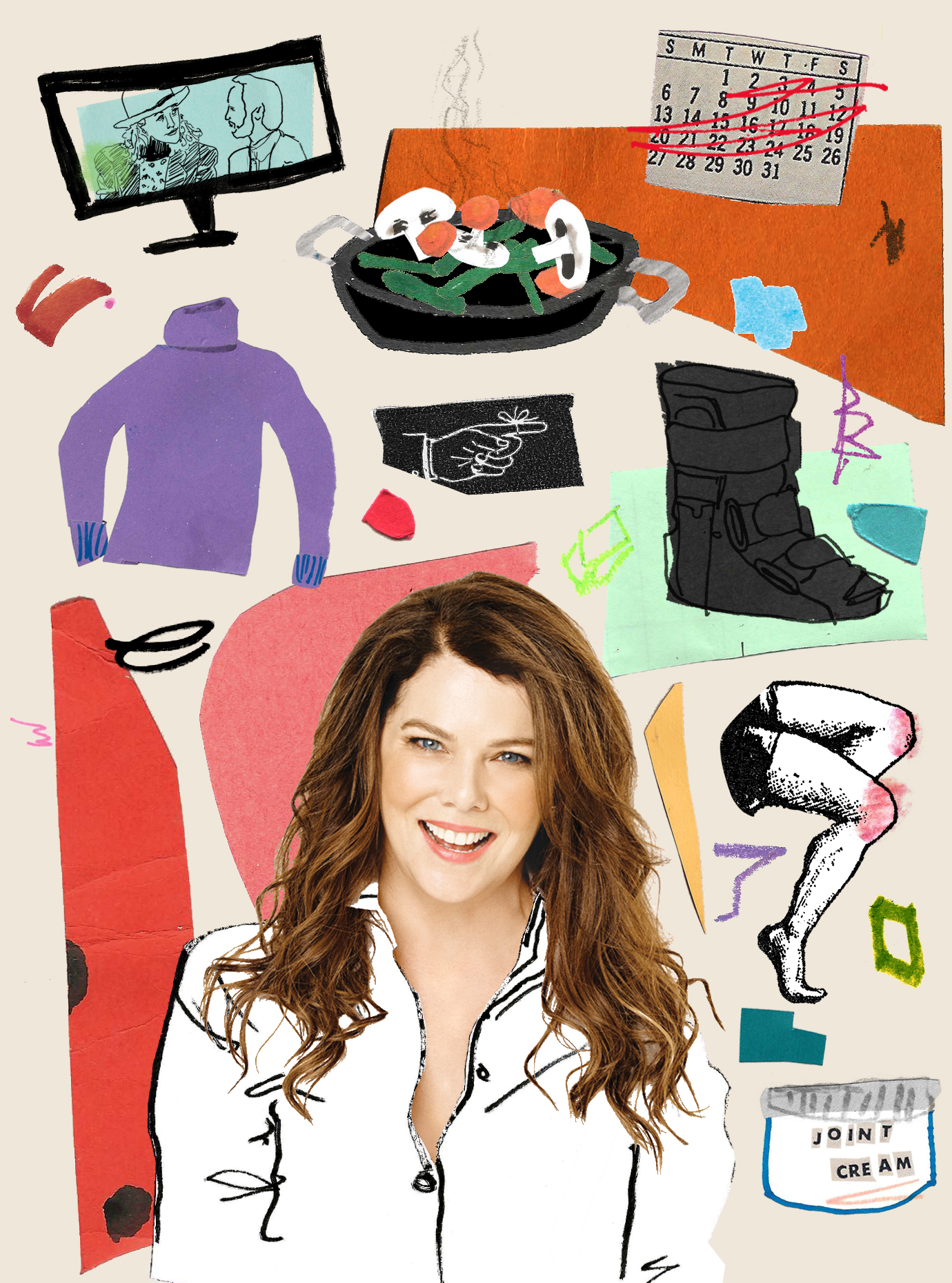

Fast forward to one day soon after I turned 50, and I again fell for no reason. I slipped on the stairs and tried to save the iPad I was holding. The iPad survived, but my foot was broken. Then, later that year, while I was on a ski trip, I fell again and broke my wrist. I wish I could tell you that—given I was on a ski trip—I was skiing when I fell, but I was merely walking to meet a friend for lunch. The broken wrist was a more serious injury that required surgery, recovery, and physical therapy, and I still have a Frankensteinian amount of metal in there holding it all together.

I’m not sure when exactly it is that you don’t feel as young as you used to, but spending a day purchasing specialty items from a hospital supply store might be one indication. I’d never been to such a place before, but in just one year I went several times to purchase a giant boot to support my foot while it healed, then an assortment of wrist guards, and a thing that looked like a massive Swiss cheese that provided multiple ways to elevate whichever ailing limb needed it. Suddenly, my freezer was full of gel packs that could be inserted into slings and Velcro foot wraps, and I was forever driving to Beverly Hills to get parts of myself X-rayed. Even after the injuries healed, I didn’t get rid of any of these glamorous items, because it occurred to me that this could be the beginning of a trend.

As a result of these injuries, not to mention turning 50, I started to think a lot more about what it means to get older. It occurred to me that I had attended Diane Keaton’s 60th birthday party. (The invitations were printed on beautiful, thick, eggshell-colored cards that simply said, “Diane is 60,” in a black, old-fashioned typewriter font. I framed mine.) Sixty was an age that seemed impossibly far away at the time, and I realized that I was now closer to that number than I felt—and there was no amount of spa treatments or fasts or yoga classes that could do anything about that.

When I talk about aging, I’m not talking about the Terrible Horrible stuff whose likelihood may increase as we get older. I’m not talking about serious diseases or conditions requiring regular visits to the hospital. I’m talking about things that are mainly just annoying but also mystifying in that they show up without warning. I’m talking about the moment you realize you’ve turned 2-p.m.-Sunday-matinee-years-old because going to Times Square at 8 p.m. seems like a ridiculous thing to do, and suddenly your entire lunch conversations revolve around the best cream for sore joints. On the one hand, this development is OK because you’re having these conversations with your friends, who have also started falling for no reason, and you have people with whom to discuss these things over steamed vegetables and mashed potatoes because spicy foods just don’t agree with you anymore. On the other hand, this change sneaks up on you, and like any sneak, it gives you a bit of a scare.

Of course, I’d thought about aging before, since I work in an industry obsessed with how people look. But—whether it mattered to my profession or not—the concept that this getting older thing was a train that only moved in one direction had somehow not fully struck me until the year of broken bones.

Read More: Tina Fey Says Aging Is the Biggest Challenge She Has Faced in Hollywood

That same year, in therapy, I compared my feelings of being panicked about getting something done to Joan Cusack racing to get the videotape to the newsroom in Broadcast News, and the therapist looked at me blankly. That my film references were not those of my slightly younger therapist, and that professionals to whom I entrusted my medical care were now younger than I, was another change I didn’t see coming. You spend so much of your early life looking up to people older than you and figuring they know things you’ll someday know too, then one day you’re looking for advice from a doctor who (hopefully) knows more than you do except for not having seen Broadcast News, and life’s questions become more complicated: can you really trust someone with your mental health who doesn’t have most of every Jim Brooks movie memorized? Maybe you knew more than you thought you did when you thought older people knew more?

During the year of broken bones, I reread all of Nora Ephron’s essays. I am a rereader of: everything by J. D. Salinger, everything by Nora Ephron and Carrie Fisher, and Jane Austen’s novels in steady rotation. I don’t know what this says about me, but this time, one essay of Ephron’s bothered me in a way it hadn’t before.

“I Feel Bad About My Neck” is a brief and funny essay in the book of the same title. All of Ephron’s essays, scripts, some interviews, and some New Yorker pieces are also gathered in a collection called The Most of Nora Ephron, which is one of my treasured bedside table books that I turn to frequently. In this piece, Ephron notices herself and her friends trying every type of shirt collar and turtleneck sweater in order to hide their aging necks. She notices this and then concludes in her sharp, observant way that it’s a shared fate, part of life, and there’s nothing really to be done about it.

Read More: Justine Bateman’s Aging Face and Why She Doesn’t Think It Needs ‘Fixing’

Incidentally, everything I’ve read about aging, whether fiction or nonfiction, has been written by a woman. Perhaps I have missed the many essays written by men worried about their necks aging because I’m a woman looking to see what women I admire have to say on the subject, or maybe I’m correct that male writers don’t spend as much time thinking about their necks as female writers do. I just googled “men, writing, necks,” and the first thing that came up was, “Why are men so attracted to women’s necks?” Thus concludes my research.

I cannot possibly say anything about aging, or anything else, better than Nora Ephron said it, and I’m not even going to try. It just bothers me that this incredible woman—who was a reporter, a novelist, the screenwriter of When Harry Met Sally among other classics, a director, and a producer—had anything to worry about regarding her neck. She wasn’t going to be filmed and judged and picked apart and criticized over it, because she wasn’t an actor and Twitter hadn’t been invented yet. But still, she worried enough to turn it into comedy, which is what brilliant comedic writers do, I guess, especially if they’re women.

When my mother’s cancer came back for a second time, years after she’d been in remission, this is how she told me: “Well, at least I won’t have to get a face-lift.” This was her gallows humor, but also a thought I knew she’d genuinely had. Death versus maintaining youthful beauty should not be a competition. Sometimes, a person will tell me that I “look exactly the same” as I did years before. And I always think, No, I don’t, and if I did it would not be due to natural practices—and what kind of pressure is that?

In Ephron’s essay, she acknowledges that she could have work done on her neck, but that would go along with having to get a face-lift—something she is clear she would never do. So, she resigns herself to living with something that bugs her and moves on. Today, the line is much blurrier. You can still draw a line at face-lifts, but there are all sorts of lasers that (supposedly) tighten your skin, machines that (supposedly) shrink fat cells, injections that (supposedly) restimulate collagen production. And there are “threads,” which are a barbed wire–shaped length of some other youthful substance designed to be shot into your face at various points to lift it up. But it will sag again eventually as the substance is absorbed, like a slowly dissolving clothesline. You redo them every year or so, and if you turn your head too sharply right after the injections, they can rupture.

Read More: Botox Is the Drug That’s Treating Everything

You might think that we in Hollywood all know who is doing what and can therefore decide what works for us, but we don’t. The people who know are the makeup artists, and none of the good ones name names. They might tell you what’s trending, but they won’t say who is doing it. They might call their A-list celebrities “Everyone,” as in: “Everyone is loving the threads. Everyone thinks that CoolSculpting doesn’t work.” Or: “No one is doing that anymore. Everyone is totally over that procedure/doctor/fad.”

I wish “Everyone” would just publish their activities to be studied in some sort of medical journal for aging actors. That way we could all distinguish between what’s real and what’s fake, what are the results of genetic blessings and what are the results of pricey doctor’s visits, and then decide for ourselves. Or at least let the secrets to success be publicly acknowledged somehow, like in the special credits at the end of a movie. “The producers would like to thank Restylane, Botox, Thermage, and the Brazilian Butt Lift.”

Read More: People Are Getting Plastic Surgery to Look Like Social Media Filters

The me that looked my “best” was a me that smoked, was underfed, ran high with anxiety, didn’t get enough sleep, and still never felt good enough. And gradually, whatever that machine was and whatever adrenaline was fueling it began to break down, and I just couldn’t do it anymore. It was around that time that I began to wonder: at what point is it OK to stop trying to “look exactly the same”?

Ephron answers that question in her essay. And maybe there’s a reason there aren’t as many men writing about aging, and the reason isn’t that they aren’t thinking about it. Maybe—like my mother did, like Ephron did—turning fears about aging and mortality into contemplation and comedy is just one of those things women are better at. And perhaps this is not a burden but should be a point of pride. We get to bond with each other with gallows humor and honesty, a more constructive—even joyous—response to fears about middle life and its injustices than, say, buying a flashy sports car (unless that gives you joy). All the Restylane in the world won’t make 80 the new 30, so why not laugh about it? Maybe the through line here is, “Let’s all give up!”—a resigned but cheery call to inaction.

From the book HAVE I TOLD YOU THIS ALREADY?: Stories I Don’t Want to Forget to Remember by Lauren Graham. Copyright © 2022 by Lauren Graham. Published by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com