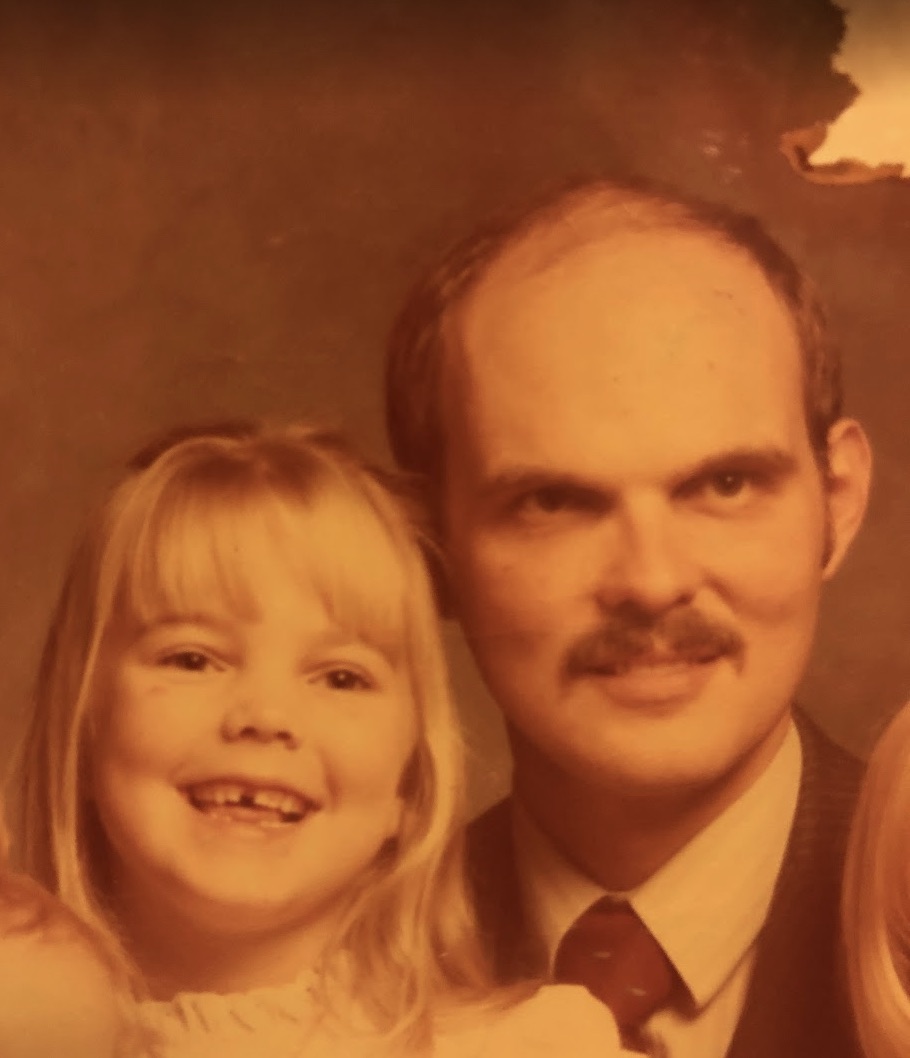

There’s a photo of my family from November 1981, when we are still living in Greenville, S.C. I remember that I lost my first tooth while we were sitting in the studio’s waiting area at Sears. In the photo, my parents are nearly two decades younger than I am now. Dad has a trim brown mustache and three wisps of hair that don’t quite cover his bald spot. Mom wears a sweater vest over a collared blouse, and she has a pixie haircut. I’m 6, with long blonde hair, freshly cut bangs, and a tooth-size hole in my smile. Evan and Katje are toddlers, just 1 and 3 years old. We’re all wearing our pink Easter outfits.

If there were an instruction manual for the modern American family of the 20th century, this photo could have been on its cover. Dad, the son of a minister, had gone to law school and was working in-house at a Fortune 500 company. Mom cared for us at home full-time. Our earliest years were crammed with dance lessons, playdates, and birthday parties that Mom planned and hosted herself.

But these identities obscured secrets, hidden shames so pervasive and toxic that although they went unnamed, they couldn’t be entirely concealed. As a child, Dad had nurtured crushes on boys. As a teen, Mom had been romantically involved with a young man who turned out to be an alleged murderer. Their own parents had encouraged them to hide these truths. These were my grandparents’ attempts to protect their children, to love them the best way they knew how. So Mom and Dad kept their secrets, from each other and even from themselves, as they grew up, got together, and built a home. They focused on conforming to expectations, attending Sunday School, following what they perceived to be the rules for an upper middle class American family in the 1980s. But as much as you can hide the things that bring you shame, you cannot banish a past. Katje, Evan, and I modeled our behavior on our parents. Through watching them and being parented by them, we learned what we could and couldn’t share about ourselves.

Read More: There Is No Longer Any Such Thing as a Typical Family

For more than two decades, the five of us lived with these secrets, our parents each growing more depressed and distant from each other and from us. Mom’s depressions led her to act erratically. Dad’s attention always felt like that which we afford each other when really we are thinking about something else. Katje, Evan, and I all knew something was amiss, but we couldn’t articulate why things felt so heavy and unpredictable at home. Each of us found ways to manage this stress; each of us wondered if maybe we were the problem.

Then, in the space of five years, everything changed. We all came out.

Looking back on that time, I’ve come to take an expansive view of that idea, of what it means to come out. I realize now that everyone has a closet. We are all born out of sync with external expectations as we perceive them. In our own ways, none of us fits in. In their youth, my parents were taught that this was their fault. They stuffed some aspects of themselves so deeply away that they didn’t understand they were hurting themselves.

For me, as for my siblings and my father, coming into alignment with myself meant coming to terms with my sexuality. Not every coming out looks like that, but for us, being queer was a reason to engage deeply in the process of self-actualization. In doing so, we gained community beyond our family—and, crucially, within it. We began to find one another when we found ourselves.

I was first to come out, in 1994. I had known I was gay by the time I entered sixth grade, but this seemed like a problem to conceal. I didn’t meet other queer people until I arrived at Brown University and attended a group for kids who were questioning their sexuality. I told my parents in the car on the ride home from my second year of college. In the front passenger seat, Mom cried. She said she thought my cousin was gay because he was so emotional. And then she told me she loved me, no matter what.

Read More: Coming Out to My Kid Helped Me Come Out to Myself

Beside her, Dad stared ahead, his hands fixed at 10 and two. He said nothing.

The next day, I was perched at the breakfast bar when he stopped in the kitchen to pour himself a bowl of Grape Nuts with skim milk. “I thought I was gay once, too,” he said.

“Really, dad?” I responded. “What did you do about it?”

Dad drained the last of his milk with a quick slurp and stood to grab his briefcase. “Well, you make choices,” he said. “I married your mom.” Then he headed out to work. I stood in the kitchen, dumbstruck, starting to piece together a truth that would take much more time to see clearly.

It was three years later when Dad’s secret surfaced, very much against his will, after my sister logged onto the computer in the study and discovered his infidelity. This started a chain reaction that would destroy the family we knew, cause our relationships with each other to disintegrate, and force each of us to reckon with our own identities. Our parents’ marriage exploded, leaving them incapable of showing up for us as they tried to survive their own crises. Everyone was caught up in this debacle. Everyone hurt, and in the process, without meaning to, we all hurt each other. But we also did the hard work involved in self-reflection. We had no choice. By the time my parents’ divorce was final, Katje had told us she was bisexual. Evan had assumed male pronouns, revealing that he was transgender. And mom had found voice to come out as a survivor of a series of heinous crimes.

Over time, released of our shame, we cobbled together relationships with one another again. This process of repair wasn’t always intuitive, nor was it linear. But as each of us became more comfortable with ourselves, we had a newfound capacity to enjoy each other. This change happened over many years. It wasn’t something we discussed. It was just true.

Then came the pandemic. My wife and I had a toddler at home when the world changed. I remember the week when everything shifted in Brooklyn, where we live. The playgrounds closed, and groceries were harder to come by. Most people talk about the sound of sirens on the streets in those early weeks, but I also remember the chirping of the birds. The city, absent traffic, became an avian sanctuary, or maybe they were always there, but I hadn’t noticed them above the daily cacophony. A couple of weeks in, my wife and I loaded our Subaru with everything we could fit and drove 18 hours to her parents’ home in Mississippi, where we stayed for months.

The gift of the pandemic was a shift in perspective. In 2020, we had time—hours that accumulated into days, which rolled on and on with little structure. Our goals dissolved. Our social lives disappeared. After an early frenetic month of Zoom cocktail hours and yoga classes, I fell out of touch with most people. But the five of us—my father, my mother, my sister, my brother, and I—leaned on one another. Quarantining in five separate houses in four different states, we called and texted and gathered on Zoom. With COVID-19 raging, we were aware of our mortality, conscious of the fact that we had to work for our connectedness. It was clear that we all valued it. We were close.

I wondered: how did this happen? Anyone who had known us during my siblings’ and my adolescence, when we all were closeted, would never have predicted this. So I asked my four family members whether I could try, at least, to synthesize the disparate threads of our history into a narrative. Could I interview each of them about coming out?

The first person to bless this idea was my mom. Dad and Evan signed on shortly after. “It scares me,” Evan told me. “Which is why I think we should do it.” Katje let the idea sit for a few weeks, taking the time to fully consider the implications of sharing her thoughts, filtered through my words. But then she agreed, too, because that is what we have become: a group of people who are willing to trust one another.

When I began, I thought I was looking for a way to stitch together a common narrative, one story on which all five of us could agree: this is the story of our family. But what I discovered is that there is no one story. There are only unreliable shadows of memories, hardened by our biases and our emotions. Taken together, there is one lesson that emerges: Had we not come out, we would have been lost to one another. Having survived the hardest edges of our early years, when we weren’t great to each other, we would likely have sought refuge in others. In this way, we’d also be lost to ourselves.

We all have ways in which we don’t fit in and truths about ourselves that we feel we must conceal. There is freedom in sharing these things. I think about this now as I raise my own children. It’s my hope that they will always be moving closer to the most authentic versions of themselves—that they will always be coming out.

Read More: My Brother’s Pregnancy and the Making of a New American Family

There’s a photograph of my family snapped in August 2021. We’ve organized a trip to Oregon. We plan to visit Dad and his husband, who live on the Coast, but first we’re celebrating Mom’s 70th birthday. The photo is taken at the end of a gentle hiking trail called Little Zig Zag Falls, and no one looks at the camera. Mom is perched on a tree stump. Her hair is long, hanging in two braids, and her t-shirt says “Radical Empathy.” Her three oldest grandchildren, aged 2, 4, and 5, are throwing pine cones in the stream at the base of the waterfall, their arms a blur of motion. Just out of frame, we kids are trying to keep up, grown, tromping through soft beds of pine needles, smiling.

Hempel is the author of The Family Outing, to be published Oct. 4.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com