The greatest female athlete of all time—check that: perhaps the greatest athlete of all time—has been thinking a lot about the reason she’s vowed to hang up her racket for good.

“Olympia doesn’t like when I play tennis,” Serena Williams says plainly about her daughter, Alexis Olympia Ohanian Jr. When Williams told Olympia, who turns 5 on Sept. 1, that she was soon to be done with the life that made her an inspiration to millions, Olympia’s reply was as joyful as her mother’s celebrations after so many Grand Slam wins: a fist-pumping “Yes!”

“That kind of makes me sad,” says Williams, leaning forward in her chair in the library of a New York City hotel. “And brings anxiety to my heart.” No kid understands their parent’s absence. But Williams has spent the last few years of her incomparable career tormented by what she’s been sacrificing in order to keep going. “It’s hard to completely commit,” says Williams, “when your flesh and blood is saying, Aw.”

Buy a print of “The Greatest” cover here

Olympia would also like to be a big sister. One day in August, she blew on a dandelion, wishing for a baby sister. “This is what I have to deal with, on a daily,” Williams says, with the commiseration familiar to all parents of young kids. And yet choosing this path requires a calculus that superstar fathers don’t have to make. Tom Brady, father of three, can retire and unretire at 44; LeBron James, father of three, can sign a two-year, $97.1 million contract extension at 37. “It comes to a point where women sometimes have to make different choices than men, if they want to raise a family,” says Williams, who turns 41 in late September. “It’s just black and white. You make a choice or you don’t.”

Biology may have forced her hand, but Williams insists she’s at peace with her decision. “There is no anger,” she says. “I’m ready for the transition.” She’s thought about what’s next, without knowing how it will feel. Williams will re-direct her curiosity and drive into her investment firm, Serena Ventures. She’ll kindle her spiritual life. She’ll evolve as a mom. “I think I’m good at it,” she says of parenthood. “But I want to explore if I can be great at it.”

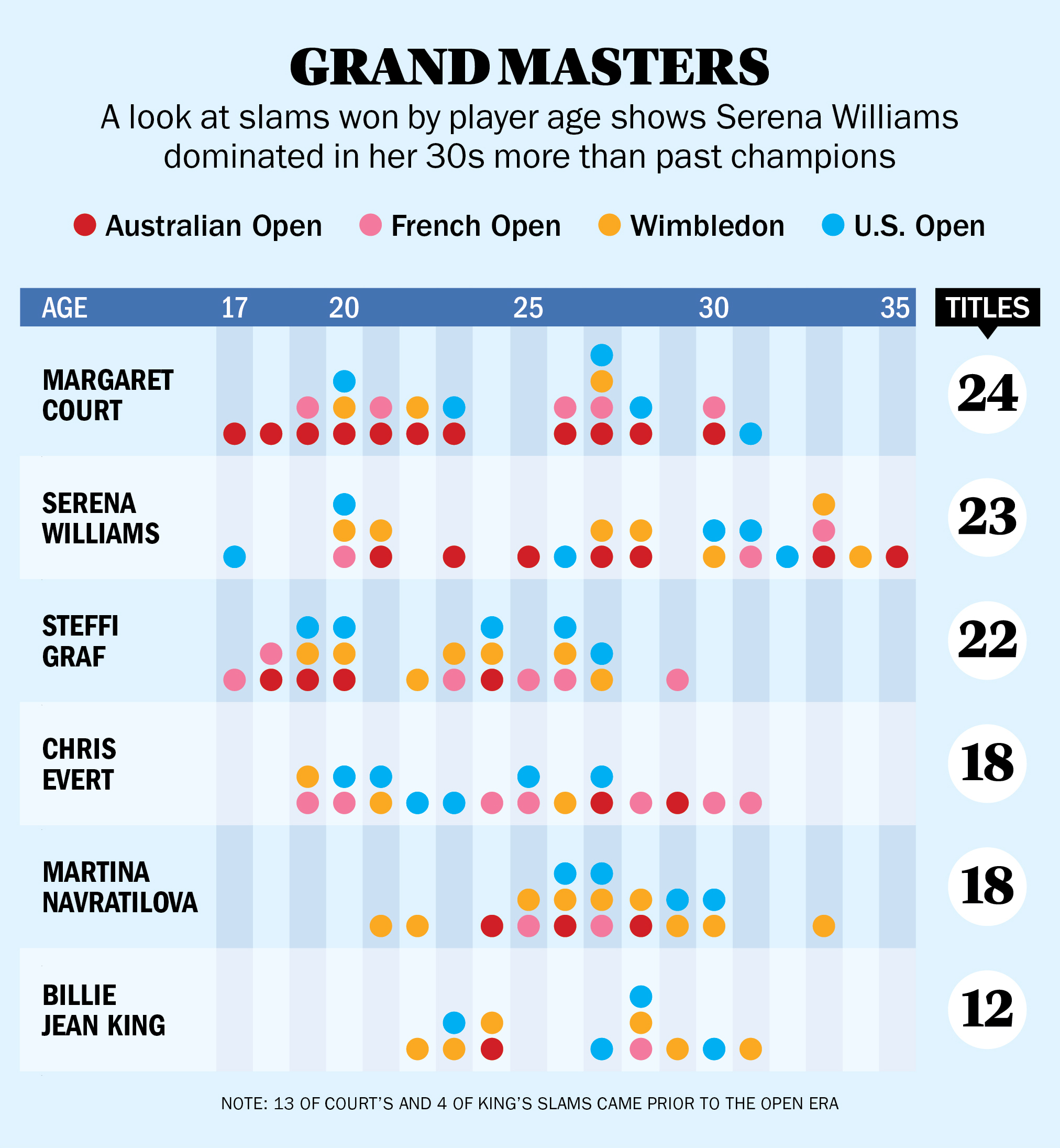

Greatness is something she knows well. No tennis player, male or female, has won more major championships in the Open Era—the period starting in 1968 when the Grand Slam tournaments allowed professionals—than Serena Williams. (Australia’s Margaret Court owns the all-time record, with 24 Grand Slams.) Williams earned 10 of those 23 titles after the age of 30, a time when most players retire or plummet in the rankings. But for all that Williams accomplished on the court, it’s what she has meant off the court that makes her the most consequential athlete of the 21st century, full stop. She, along with older sister Venus, took over a country-club sport with resistance to a pair of Black sisters from Compton, Calif., baked into its DNA. She helped change behavioral expectations for female athletes, and by extension women in all workplaces, by exuding power and passion—and bringing her full self—to her hard-court office. She rewrote the book on body image. When pundits, racists, and no small number of idiots slurred her physical appearance or laughed her off as “masculine,” she doubled down on photo shoots and flexes.

Her very being sparked a multitude of crucial conversations. In 2018, her run to the Wimbledon final—months after Olympia’s delivery led to a life-threatening pulmonary embolism and hematoma that required multiple surgeries—inspired millions of moms. But that chatter shifted, in an instant. On a September afternoon, a male umpire penalized Williams at a key moment in the U.S. Open final, for a verbal outburst. She argued that men got away with much worse. Serena lost to Naomi Osaka, and the fallout prompted debates about decorum, fair play, gender discrimination, racial discrimination, letter of the law, spirit of the law, and unconscious biases.

All from a Serena Williams tennis match.

Osaka, who has since won three more Grand Slams, never would have picked up a tennis racket if it weren’t for Williams. “I remember as a kid watching in awe, and I was so happy to be seeing a strong Black woman on my screen,” she tells TIME. “Even though she is retiring, her legacy definitely lives on through Coco [Gauff], Sloane [Stephens], Madison [Keys], and other women of color at the top of their game. Serena is unequivocally the best athlete ever. Forget female athlete, I mean athlete. No one else has changed her sport as much as she did and against all odds.”

When informed of Osaka’s comment during our late-August conversation in New York, Williams demurs when the talk turns to being the GOAT. That is, up to a point.

“I don’t know any other person that has won a Grand Slam or a championship in the NBA or anything else nine weeks pregnant,” she says. She laughs, a habit when she wants to make a serious point. “A two-week event. That tournament, I relied on my brain. An athlete isn’t just about what an animal you are physically, like a specimen. It’s using everything. Your mind, your body, everything. And doing that for 20 years. And doing it against people that come against you and play the best game of their life. Every single time.

“You can come to your own conclusion after that.”

The Williams sisters’ backstory is filled with tales of their competitive exploits. “There was a rage, a burning desire that I’ve never seen in two little girls, ever,” says Rick Macci, one of Venus and Serena’s earliest coaches. “And I haven’t seen to this day.”

Richard Williams’ genius was that while many tennis dads suffocate their children, he nurtured their talent while encouraging them to be kids. On rainy days at Macci’s Florida training facility, they’d study in his office. Richard kept them off the junior circuit, on the advice of absolutely no one. After they faced Hall of Fame legends Billie Jean King and Rosie Casals in an exhibition doubles match, Macci heard both sisters complimenting their own performances. He turned around. Venus, 11, and Serena, 10, were talking to a doll.

Childlike curiosity intact, the sisters went on to learn multiple languages and diversify their interests. Serena has dabbled in finance, fashion, acting, and film production; she’s on track to be the first female athlete to become a billionaire. Early in her career, she faced criticism for moonlighting outside of tennis. She was supposedly unfocused, distracted. She again rewrote the rules. Expanding her palette prevented the burnout that previously plagued so many players. No woman has won more big matches in her later years.

Williams conquered her first major, the 1999 U.S. Open, at 17. “It really was a different mentality of tennis,” says Chris Evert, the 18-time major champion. “Go for everything. When you’re under pressure, you’re more aggressive.” Serena and Venus wore braids with beads in those early years on tour. Even this seemingly small fashion choice carried meaning. “The tennis world was not accustomed to seeing Black girls show up adorned in styles reflecting their African American cultural heritage, as opposed to wearing styles that blended in,” says Tera Hunter, a professor of African American studies at Princeton University.

Around this time, Williams met Kelly Rowland, of the pop supergroup Destiny’s Child, after a concert. She invited Rowland to come to a match. “I’m going to be really good,” Serena vowed. “As soon as she said that, I was struck by her,” says Rowland. She remembers sitting in Serena’s box during a match when she was down a set. “You feel an energy shift,” says Rowland. “Something’s about to happen. It’s watching her get upset, like we do as people, and then understanding she had to calm herself down. It was her having this controlled kind of space she had made for herself. And then it was about her dominating. And it was so unapologetic. It wasn’t anything she had to say. It was like, ‘I’m about to take back what’s mine.’ I needed that at that moment. It fed me.”

It wasn’t just women who were taking cues from the Williams sisters. An aspiring young race-car driver named Lewis Hamilton tuned in to Venus’ and Serena’s matches from a public housing complex north of London. “They were the two most inspiring sports figures for me,” Hamilton tells TIME. “Especially growing up in my sport, where I’m the only person of color, seeing these two prominent figures, also the only people of color, really gave me a lot of confidence that I can do something similar. It’s not impossible.” Hamilton, winner of seven Formula One titles—tied for the most in history—has also bonded with Serena. She carries a small microphone in her handbag when they go out, for impromptu karaoke.

Over a quarter-century on tour, Williams has had her share of downturns. She suffered knee, ankle, shoulder, foot, hamstring, and Achilles injuries. She grieved the death of older sister Yetunde Price, who was killed in a 2003 shooting, in a case of mistaken identity. She was vilified at the 2009 U.S. Open for threatening a lineswoman after a foot-fault call. Williams apologized. And then she won two more Slams the next year.

In February 2011, Williams was supposed to fly from Los Angeles to New York City, before going off to London for a fashion show. She canceled plans at the last minute, choosing to hang out with Venus instead. That night, she checked into a hospital with breathing difficulties: she suffered a pulmonary embolism and had blood clotting in her lungs. If she had been stuck on a cross-country flight, Williams believes she more than likely would have died. She thought she’d never play tennis again. Ten more Grand Slams followed.

When Williams found out she was pregnant right before the 2017 Australian Open, she played on with little hesitation. “Athletes understand their bodies a million times better than the rest of us,” says her husband Alexis Ohanian, the venture-capital investor who co-founded Reddit. “Even though the doctor was like, ‘You’ve got to take it easy, 100° heat, yadda, yadda, yadda,’ Serena said, ‘I got this.’ As long as she was confident, I was confident.” Serena told her husband that she didn’t drop a set the entire tournament because she knew it was best to get off the court quickly, for the baby’s sake. The victory broke Steffi Graf’s Open Era record for major titles.

Read more: Serena Williams Opens Up About Her Complicated Comeback, Motherhood and Making Time to Be Selfish

Allyson Felix was among those watching. The Olympic gold medalist discovered she was pregnant the next year, in 2018; she continued training and competing. Like Williams, Felix had a life-threatening delivery of her daughter: after developing preeclampsia. Felix watched as Williams grinded her way back, ascending to the Wimbledon and U.S. Open finals in the year after Olympia was born. Felix charted a similar path. At the Tokyo Olympics, at 35, Felix won bronze in the 400-m and a relay gold to become the most decorated female Olympic track-and-field athlete in history, and pass Carl Lewis for the most Olympic track-and-field medals won by an American. “I was heavily influenced by her experience and the comeback,” says Felix. “Here’s the ultimate example that it can be done.”

As her career extended, Williams publicly embraced causes she had long valued privately. In 2015, she again played at Indian Wells, the prominent Southern California tournament she had boycotted since 2001 after feeling an undercurrent of racist jeering. (Fans were angry that Venus pulled out of a semifinal against Serena with an injury; they were convinced that Richard had engineered that outcome.) As part of her return, Williams helped raise money for the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit dedicated to racial justice and fighting mass incarceration. “Serena’s not just taking punches, she punches back,” says Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza. “She’s showing us that it’s important to belong to yourself. And ultimately, that is a motto that I hold, and I know that’s one that she lives.”

Rowland gets emotional when asked to try to describe her friend’s influence on the world. “For a young Black girl, to have survived the spaces where she wasn’t welcomed, she stood with pride,” says Rowland. “She represented for all of us, when we couldn’t do it. She made it OK. Claim your space. Even when they’re calling you words you’d never answer to. You can’t hear it. Don’t hear it. I’m sure that was a very scary place to be. But to do it, and you’re the first to do it, the way you do it, with our own unique way, with style and with grace and unapologetic of your greatness,” Rowland says, choking back tears. “That took some … f-cking guts.”

It’s been too long a road for Williams to shy away from what she’s done. She owns it. Deservedly. Unapologetically. And it’s rooted in what she knows she and her sister have meant to the sport that they both shaped and were shaped by. “We changed the game of tennis,” Williams says. “We changed how people play, period. People never attacked. People never took balls early. People never served like this. People never had to play so hard to beat two Black girls from Compton.”

Off the court, she’s helped transform beauty standards—often in the face of crass scrutiny and racist tropes. “A lot of people feel they’re not pretty or they’re not cute enough because their skin is dark,” she says. But she insists she never felt that way, despite all the shots directed her way. “I think people could feel my confidence, because I was always told, ‘You look great. Be Black and be proud.’” There were too few prominent examples in mainstream sports before Venus and Serena—and few who won so regularly and defiantly. “Giving them that confidence, that motivation, is something that has literally never been done,” says Williams. “You don’t let the world decide beauty. And me being thicker or whatever, I mean, curves are popular now. Butts are popular. I’m trying to lose mine, and people are trying to get mine.”

Knowing insight delivered in a self-deprecating package is a Williams signature. But press a little and she states plainly what she believes her legacy is. “Confidence and self-belief,” Williams says. “And teaching other Black kids, in particular Black girls, they can do it too.” She lists the current top Black players on the pro tour—like Osaka and Gauff and Stephens—who represent the emergent generation. “No one has ever been able to tell such an inspiring, authentic story,” she says. “You live through my mistakes. You live through my ups, you live through my downs. The surgeries, and the comebacks. And it’s also a tale of never letting anyone write your story. A lot of people can relate to that. Always be authentically you. Own who you are. And love you. It’s a big tale of self-love.”

Read more: Serena Williams: 100 Women of the Year

She laughs. In her final days as a pro tennis player, she also shed some tears. She bawled while working on her Aug. 9 Vogue essay announcing her imminent farewell. Walking away from the game you’ve spent your life mastering is complicated. And it’s not to say she won’t decide to pick up a racket again one day. But her next chapter isn’t about finding 5 o’clock somewhere. Serena Ventures has invested in more than a dozen companies now worth more than $1 billion, including Master-Class, Impossible Foods, and Tonal. Nearly 80% of the companies in the firm’s portfolio were founded by women or people of color. “It’s not that I’ve lost my passion for tennis,” Williams says. “I just get more love and more joy out of what I do in the VC space.”

But expanding her family is paramount. “I can’t imagine my life without my sisters,” she says. “When I look at Olympia, I’m really not performing at my peak, by not trying harder to give her that sibling. Coming from a big family, and coming from five, there’s nothing better.”

As Williams prepped for the U.S. Open, she felt her game finally coming along after such a long layoff. Before Wimbledon, where she lost in the first round, Williams hadn’t played in a year because of a hamstring injury. The progress is bittersweet. “I can see my improvement, and I’m like, Dang, I’ll be good in January,” she says. Once the Australian Open comes along, she might pine for another trip down under. “I’m already thinking that,” Williams says. But would she go? “I’m not doing that,” she insists.

So this is it. One last dance in New York City. One final message to millions. “Thank you so much,” she says. “I am so overwhelmed. It’s just been an incredible, incredible ride, and I’m so happy that you guys are on it with me.” Williams stops, nods, brings her hands together, in the blessed position. “And I love you.”

—With reporting by Mariah Espada and Julia Zorthian

Styled by Kesha McLeod; hair by Dhairius; make-up by Nadia Tayeh

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com