Historian David Hackett Fischer, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington’s Crossing, has been writing history books since 1965, and his latest, African Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals, is an encyclopedia of enslaved people’s experiences in the United States from the 17th century to the 19th century.

The book, which came out May 31, is organized by region to show how the experience of slavery differed around the country—and to show its impact in local cultures today. Fischer draws heavily on writings and oral histories by enslaved and formerly enslaved persons.

The topic of Fischer’s book is especially timely. The latest chapter of the culture wars is in large part focused on how much of America’s worst moments to teach its youngest students, sparked by the New York Times’s 1619 Project, a series of articles published in 2019 reframing the country’s origins around the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Virginia 400 years ago.

Here, Fischer talks to TIME about how he worked to strike a tone that celebrates the achievements of African Americans while acknowledging the darkest parts of this history and the legacy of enslavement. He also shared his opinion on the 1619 Project.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why is your book called African Founders?

It centers primarily on the contribution of people from nine parts of Africa, in particular, to the founding of this great Republic.

What was the most surprising piece of research that you found?

The most important things were the writings that the Africans produced in which they described their own purposes, who they were, where they came from, their own values, what they wanted, what their hopes were for a better world in America. And when they came, they began to build new societies in America around ideas of how a society should be run. And usually they had some idea of liberty and freedom and then gradually they began to have some idea of the participation of many people in the running of these places. At first, [America’s leaders were] mostly men, mostly men with property, but then it grew to include larger numbers of men, and then it began to include women. And then it began to include different ethnic groups. And America’s diversity increased. And all of that is what makes us free today and keeps us free.

And we have hundreds of writings of that sort by individual people from the very beginning of American history. This country that we have, this great Republic, grew from their purposes. And my book is to help people remember those founders and what they were trying to do, and also to understand that diversity is the key to our liberty and freedom.

I think the most important thing I found is how creative many of these Africans were and became even as they came in chains. And they learned ways to break their chains and help others become free.

Read more: ‘It’s a Struggle They Will Wage Alone.’ How Black Women Won the Right to Vote

Could you highlight one or two characters for us who could easily be taught in a K-12 school?

There are so many of them. Phillis Wheatley—she was named after the slave ship that brought her to America. Her mistress, whose name was Susanna Wheatley, taught young Phillis to read, and Phillis began to amaze people by the writings that she began to produce and publish. And then she was emancipated, and she devoted herself to emancipating others, as she had been freed.

A slave named Caesar was a man of great strength—a central figure in managing an industrial operation in New York, and employed a community of Angolan and Congo slaves and helped them become free. Peter, a doctor in New York City, helped to free other people. Mostly, the book is about slaves enlarging the idea of liberty and freedom in America—both enlarging the number of people who were free and also enlarging the idea of freedom itself.

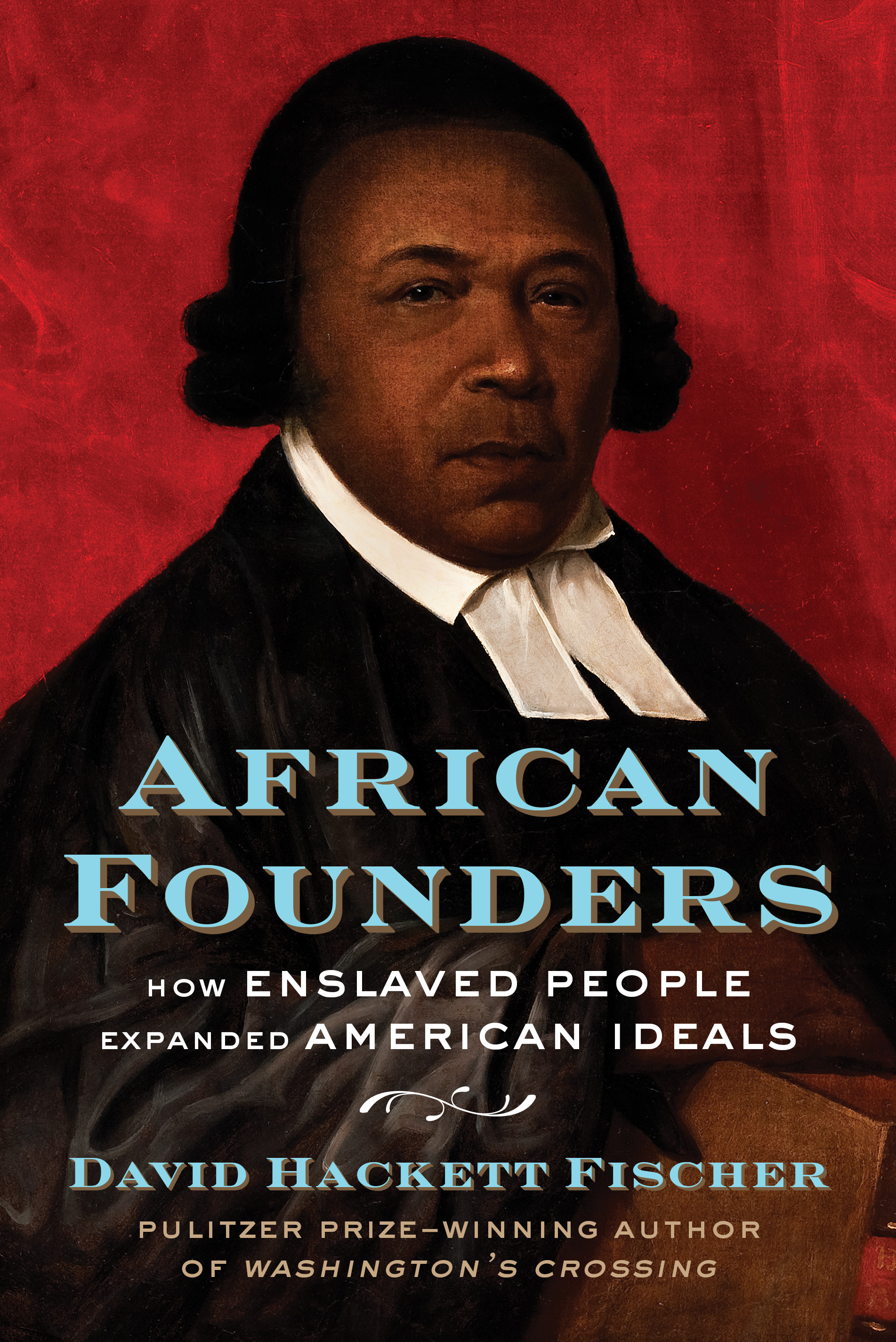

Why is Absalom Jones on the cover of the book? Why is he significant?

He was a very serious man who became an important minister and then helped to build institutions for free Africans in his region, which was New England. And also he was interested in enlarging the idea and instinct of freedom and expanding the institutions of a free society, which is what we have today. And you will see that these were very important to the founding of African churches in America.

What’s the biggest lesson you want readers to learn?

The central idea is the importance of what Africans did to help found this free Republic and how they made it more free than it otherwise would have been. We are all in their debt. And they have also given us the obligation of making it yet more free.

The subject of your book was recently popularized by the New York Times’s “1619 Project.” How do you see your book fitting into the conversation that that feature started?

They’re centered too much on what went wrong and too little on the creativity of people who are responding to what went wrong. And I want to emphasize the creativity. I think that’s much more important than carrying on about racism in America.

It’s about the people who found ways to overcome that, and take us beyond that and to make us less racist than we had been. That’s the big story in America. The big story is not that we were racist. The big story is that we overcame that. And we still have a long way to go. And I want to celebrate that.

There’s a debate going on about how much of American history—the good, the bad—to teach to young students. Many American students don’t get an in-depth education on the darkest chapters of American history until college. What do you think is the right balance to strike?

What I’m trying to do is not to dwell on the dark side. There is plenty of writing about the evils, the horror of slavery. And I’m interested in the people who tried to do something about all of that, who tried to build a free system that would include those who were enslaved, the people who tried to liberate, emancipate slaves, who tried to enlarge freedom to include them—and in that process, enlarge our free institutions.

That’s what my book is about. It’s not about beating up on racism in America. There was a lot of that. But the big story in America is that we have struggled against that. And we’ve made real progress in this country. And we still have a long way to go. But I’m working to reinforce that positive story and to show how we can make it work better in the future, and not to beat up on other people.

What would you say to people who argue that we can’t fully learn from the past if we only focus on the good side of things?

I think we should ask an honest question about what happened, how things changed and why—nevermind, skewing it toward the good or the bad. I don’t think we should begin by saying we want to look for the good things or for the bad things. I think some people have stressed the dark side and others have tried to stress the bright side and I just want to find out what happened and what we can learn from it.

I think what we should do is to ask serious questions about what happened and then go with the answer, which will be in some ways positive and other ways negative. But I don’t think we should begin with positives and negatives. I think that’s not what a serious piece of history is all about.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com