Wager, also known by his African name, Apongo, was a leader of the largest slave rebellion in the 18th century British Empire. But long before taking his part in the great Jamaican insurrection of 1760– 1761, commonly called Tacky’s Revolt, he had been on a remarkable odyssey.

Apongo had been a military leader in West Africa during a period of imperial expansion and intensive warfare there. During this time, he had even been a notable guest of John Cope, a chief agent of Cape Coast Castle, Britain’s principal fort on the Gold Coast. Captured and sold at some point in the 1740s, Apongo became the property of Captain Arthur Forrest of HMS Wager, who renamed him for the Royal Navy warship. Wager came in bondage to Forrest’s plantation in Westmoreland Parish, Jamaica, where he again encountered John Cope, who had retired to his own Jamaican estate. Occasionally, Cope would entertain his acquaintance from the Old World, laying a table for weekend visits, treating the slave as a man of honor, and insinuating that Apongo would one day be redeemed and sent home. Whatever understanding there was between the two men did not outlast John Cope’s death in 1756. In the ensuing years Wager began plotting and organizing a war against the whites, and awaiting an opportune moment to strike.

Taking advantage of Britain’s Seven Years’ War against its European opponents, Wager and more than a thousand other enslaved black people on the island engaged in a series of uprisings, which began on April 7, 1760, and continued until October of the next year. Over those 18 months the rebels managed to kill 60 whites and destroy tens of thousands of pounds’ worth of property. During the suppression of the revolt and the repression that followed, over 500 black men and women were killed in battle, executed or driven to suicide. Another 500 were transported from the island for life. Considering “the extent and secrecy of its plan, the multitude of the conspirators, and the difficulty of opposing its eruptions in such a variety of different places at once,” wrote one planter who lived through the upheaval, this revolt was “more formidable than any hitherto known in the West Indies.”

According to two slaveholders who wrote histories of the conflict, the rebellion arose “at the instigation” of an African man named “Tacky, who had been a chief in Guinea,” and was organized and executed principally by people called Coromantees (or Koromantyns) from the Gold Coast—the West African region stretching between the Komoe and Volta rivers—who had an established reputation for military prowess. Slaveholders knew these Africans to be rebellious, and their notoriety has endured to this day.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Wager’s involvement in the revolt might further justify this martial reputation, but it is also part of a less familiar story. Although we are accustomed to hearing about rebels reacting against their enslavement by rising up against their masters, and about elite people in Africa falling into the hands of slavers, rarely have these accounts acknowledged the complex patterns of alliance and antagonism over time and great distance that defined relationships like those among Apongo, John Cope and Arthur Forrest. Recognizing how life histories like theirs—stories of displacement, belonging and political predicament—were intertwined helps us understand how the slave trade triggered the diasporic warfare that both created and convulsed the 18th century Atlantic world.

Apongo’s Atlantic odyssey spans the martial geography of Atlantic slavery, highlighting the entanglement of African and European empires with the massive forced migrations of the 18th century—and suggesting a new way to understand slave insurrection.

Rather than a two-sided conflict between masters and slaves, the 1760–1761 revolt was the volatile admixture of many journeys and military campaigns. The people who took part in it traveled far and endured many turns of fortune, entangling their numerous episodes into a single story. In its causes and consequences, what we know as Tacky’s Revolt combined the itineraries of many people: merchants, planters, imperial functionaries, soldiers and sailors from Europe, Africa and the Caribbean, and enslaved men, women and children, all engaged in life-and-death struggles to accumulate wealth, build state power, strike for freedom or merely survive.

Step Into History: Learn how to experience the 1963 March on Washington in virtual reality

The transatlantic slave trade extracted people from a vast region of Atlantic Africa and spread them throughout the Americas. People who had been administrative or military leaders suddenly found themselves uprooted from sustaining landscapes, scattered by currents and trade winds, and replanted in strange territories where they labored to build new social lives and regain a level of influence. Inevitably, some of them concluded that only war could end their enslavement. Mostly it was common people who found themselves caught up in slaving raids and expansionary wars, cast across the ocean and set down in alien lands where slaveholders exploited and brutalized them. When new conflicts promised to liberate them or offered rewards for serving their masters, slaves might take up arms for whichever faction presented the prospect of a better life.

This process of dispersal from a native land, transplantation and adaptation to a new and strange one is familiar to students of cultural change, who pull African, American and Atlantic history into one large, common frame to see large-scale patterns of transformation in African religion, expression and identity. A similarly expansive approach can reveal how the turmoil of enslavement and the daily hostilities of life in bondage ignited a militant response that erupted in widespread rebellions reverberating across the Americas and back to Europe.

The effect when Africans from the Gold Coast staged a series of revolts and conspiracies in the 17th and 18th centuries—most dramatically in Cartagena de Indias, Surinam, St. John, New York, Antigua and Jamaica—was to form an archipelago of insurrection stretching throughout the North Atlantic Americas. The Jamaican insurrections of 1760–1761, and further uprisings there in 1765 and 1766, were among the largest and most consequential of these.

The aims and tactics employed by the rebels made it clear to observers that many had been soldiers in Africa. As John Thornton has argued, “Africans with military experience played an important role in revolts, if not by providing all of the rebels, at least by providing enough to stiffen and increase the viability of revolts.” Beyond one or two exceptional leaders, whole cadres of people had military training and discipline, or had at least gained knowledge of defensive tactics in Africa. Indeed, many American slave revolts might be seen as extensions of African wars. Casting them as such does more than assert the importance of Africa in the making of the Atlantic world; it helps to reveal how complex networks of migration, belonging, transregional power, and conflict gave the political history of the 18th century some of its distinctive contours. Recognizing slave revolt as a species of warfare is the first step toward a new cartography of Atlantic slavery.

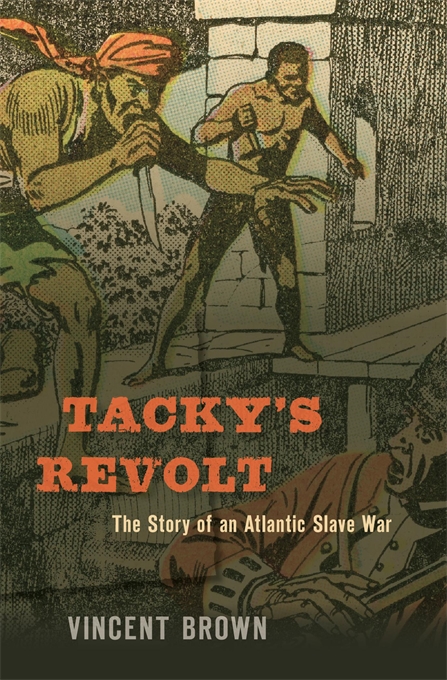

Excerpted from Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War by Vincent Brown, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright 2020 by Vincent Brown. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com