The family of Trevor Reed could breathe a sigh of relief on Wednesday, as the former U.S. Marine was transferred to U.S. custody after being detained in Russia since 2019. In exchange for Reed’s return, the U.S. sent back Russian citizen Konstantin Yaroshenko, convicted of drug-smuggling in 2011, from a Connecticut prison. Reed had been sentenced to nine years in prison in 2020 after an altercation with Russian police officers, and American officials cited his deteriorating health as a reason for the swap.

With that, Reed joins a long history of prisoner swaps in the American past. TIME spoke to Paul J. Springer, America’s Captives: Treatment of POWs from the Revolutionary War to the War on Terror to see where the Reed-Yaroshenko swap fits in with that history so far.

TIME: What is a prisoner swap?

SPRINGER: A prisoner exchange, from a military standpoint, is simply the return of personnel from two sides that are engaged in the conflict. Normally, when you have a prisoner-of-war exchange, you tend to do it on a rank-for-rank basis. So I might give you two colonels and you give me two colonels.

How far back did you find prisoner swaps go in American history?

In American history, they actually go back before the Revolutionary War because they were a normal aspect of European-style warfare. So even in the colonial wars, there were swaps of prisoners of war that occurred during wartime and then at the end of war. Virtually every peace treaty will have a provision for the return of all enemy captives.

What are the origins of laws that govern prisoner swaps today?

The standardized, “here’s how we’re going to do it” system emerged during the Thirty Years War in Europe, which was 1618 to 1648. There was a Dutch jurist named Hugo Grotius, who wrote two books on the laws of war and peace, and he had spent time as a prisoner of war. He spent a bunch of time in his works essentially codifying what he saw as the laws of civilized war, and it included the idea that you couldn’t enslave enemy captives, that they were not the possession of whoever captured them. You couldn’t kill them out of hand, you had to keep them alive, and at the end of the conflict, you had to give them back to whatever nation they served. So he’s writing that in the 1630s and 1640s. And it starts to really become the norm in Europe by about 1660-1670.

In the late 19th century, there’s a follow-on push to kind of regularize war during the American Civil War. A lot of people are pretty horrified by what they’re seeing, especially European observers. The International Committee of the Red Cross forms in Geneva in 1864, and they’re going to propagate kind of a common understanding of some of the limits of war.

Read more: How the Meaning of ‘War Crimes’ has Changed

In 1929, after World War I, most of the major powers of the world get together at Geneva again, to kind of say, “Alright, we just fought World War I and it was awful. And let’s think about how we can make war less awful because war is bad.” The 1920s have a lot of optimism about preventing future conflicts. At Geneva they say, “All right, in the event of conflicts, here’s some limits.” You can’t deliberately target civilians, for example; you have to give prisoners of war shelter, medical care, and adequate food. Basically the way they phrase it is essentially, you’ve got to maintain them at the same level of health that they were at when they were captured. In 1949, after World War II, there’s going to be another revision of Geneva. So once again, they’re basically going to sit down and say, “All right, well, World War II was awful, what was wrong with the 1929 rules? And how do we need to change them?” And so in 1949, we get some provisions in terms of, particularly, the custody and care of prisoners.

More from TIME

Are there any broad trends you observed in terms of when or why prisoner swaps happen?

They have become more rare during conflict. More and more prisoners tend to be held until the end of the fighting. There are often wartime swaps of sick and wounded prisoners, where there’s no possibility they’re going to go back into conflict. So you know, maybe you’d have an individual who’s lost a limb, for example, or who’s on the verge of death from tuberculosis, then you’re pretty likely to get a humanitarian swap. During the Korean War, for example…there was an exchange of wounded and sick prisoners. It was for humanitarian reasons; an awful lot of them were actually expected to die fairly soon after the swap, but [get to] die at home rather than die in a prison camp.

Are there any milestone prisoner swaps to know about from recent history?

Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl went missing from his unit in Afghanistan, and then wound up being swapped for five rather senior prisoners in Guantanamo Bay. That one was facilitated by a third-party government, Qatar. So essentially, they brokered the deal [in 2014]; Bergdahl got released. The five prisoners from Guantanamo were delivered to Qatar, who agreed to intern them for a period of time before releasing them. It was a pretty controversial swap. It was partially unique because he wasn’t captured by an enemy nation; he was captured by the Haqqani Network, which is classified as a terror organization and you know, we’ve all seen the Hollywood movies say, “Oh, we don’t [America doesn’t] negotiate with terrorists.” But actually we do sometimes when we need to. It was also somewhat unique because there was quite a bit of question as to whether Bowe Bergdahl had been captured or whether he had voluntarily gone over to the enemy.

So where does the Trevor Reed prisoner swap fit in the history of prison swaps?

[Reed and Yaroshenko] are civil prisoners. They’re not prisoners of war. And those types of swaps are kind of a whole different history. If what we have is somebody that the Russians accused of a crime and incarcerated, and in the United States, there’s a Russian accused of a crime and incarcerated, oftentimes, countries will throw the old diplomatic levers of power into play, and try to work out a prisoner swap.

For example, we’ve had a lot of espionage exchanges, where “I catch some of your spies, you catch some of my spies. Officially, I can execute your spies for espionage and you can execute mine, but we’ll agree to quietly make an exchange.”

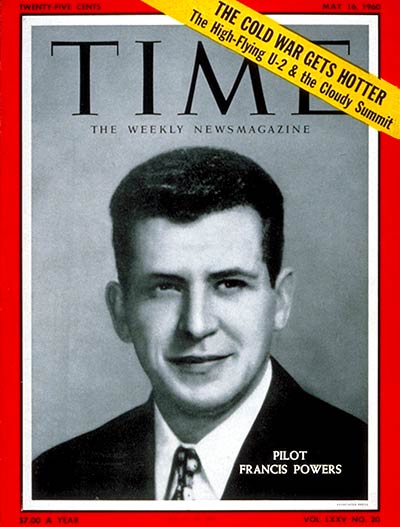

The milestone of that history is Francis Gary Powers, the U-2 pilot that got shot down on a surveillance flight over the Soviet Union in 1960, and the Soviets captured him. He’s got a cyanide pill in his uniform, but he doesn’t take it. He was supposed to kill himself to avoid capture. In his particular case, eventually we quietly wind up making an exchange to swap one of their espionage agents from the United States back to the Soviets. Tom Hanks made a movie about it called Bridge of Spies, and it’s all about the meeting on the bridge to do the physical hand-off of the two prisoners.

Read more: How Bridge of SpiesUses the Present to Shape the Past

There was a case back in the ’90s, where an American teenager got caught vandalizing cars in Singapore, and the State Department did everything in their power to try to get this kid released because the Singaporean punishment was that he was going to be caned. They did actually physically hit the kid multiple times before releasing him and banning him from the country.

You can see a lot of examples of Americans that are sentenced to death in Saudi Arabia, and so you’ll often get the State Department quietly trying to save these people from being executed by the Saudi government and making whatever concessions they need to.

There have literally been hundreds of them [civilian prisoner swaps]. They’re kind of a constant. You just don’t hear much about them usually, unless it’s somebody really famous or their family makes a lot of noise. You often see these kinds of quiet swaps, and sometimes it’s not adversarial. The State Department has a lot more of these negotiations than most people could ever possibly realize.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com