Congressional staffers spend late nights and weekends helping to broker deals and write the laws that govern the U.S. Many do so on salaries so scant they qualify for the welfare benefits they help legislate. And they’re sick of putting up with it.

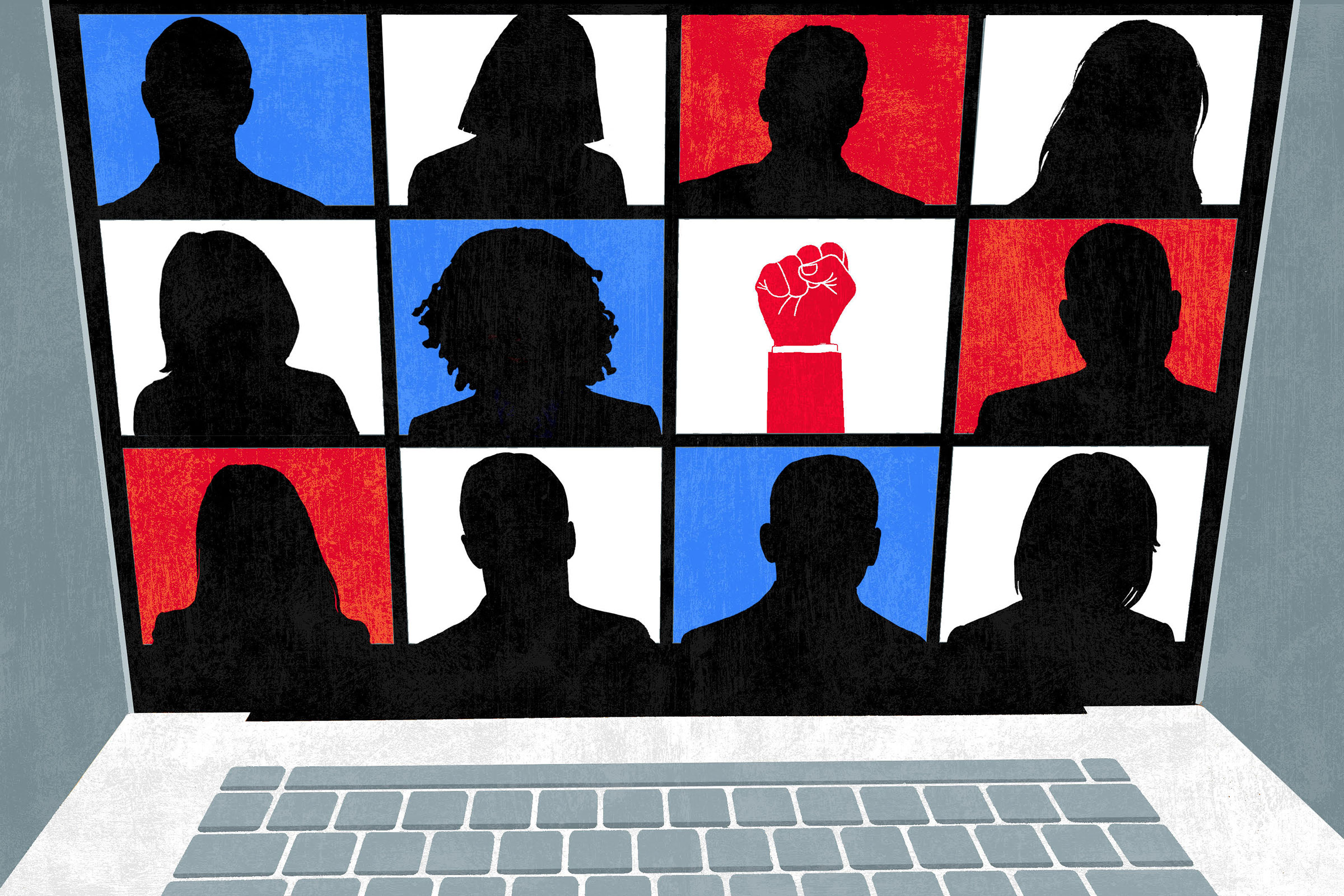

On a Thursday afternoon in February, as many members of Congress were flying back to their districts, eleven Democratic House staffers convened for a secret meeting on Zoom to discuss their plan to unionize both chambers of Congress for the first time in history. The staffers, who represent the as-yet-still-aspirational Congressional Workers Union (CWU), have two goals. The first is to get both the House and Senate to pass resolutions granting them legal protections to unionize. The second is to leverage the power unionization would provide to improve their lot. “It’s a privilege to work here,” says one staffer on the Zoom call, “but it shouldn’t be a privilege to earn a living wage here.”

Capitol Hill staffers’ gripes are not without merit. A recent analysis of 2020 data by Issue One, a nonprofit political reform group, showed that 13% of Washington-based congressional staffers—roughly 1,200 people—earn less than $42,610 annually. That’s the amount, according to a Massachusetts Institute of Technology living-wage calculator, needed to cover bare-minimum essentials like rent and groceries in Washington, D.C., the fifth most expensive city in the nation, where an average one-bedroom apartment rents for $2,444. Young people who come from working-class communities often can’t afford to take such low-paying jobs—which hurts their own careers and exacerbates the lack of low-income and minority representation in Congress.

While a handful of Hill staffers have been whispering about unionizing since December 2020, the effort lacked momentum. That changed in February, when top Democratic leaders, including President Joe Biden’s White House, announced they would, in theory, back a unionized congressional workforce. Within weeks, CWU was flooded with interest from hundreds of staffers. “It had been snowballing pretty smoothly,” says one CWU member, “until that week created an avalanche.”

But the path forward is hardly easy. One problem is that CWU members face legal risk. While federal labor laws protect most U.S. employees’ labor-organizing activities, Congress exempted itself from its own legislation, leaving Hill staffers without formal legal protections until the resolutions pass. Many fear being fired or blacklisted. (The CWU members are not named in this story because the resolution that would provide them legal protections against employer retaliation has not yet passed. TIME has verified their status as Congressional employees.)

Read More: The IRS Is Struggling to Keep Up—And That’s Bad For Everyone

Another issue is that the unionizing effort creates a problem of political optics, particularly for Democrats. So far, the CWU movement has been dominated by Democratic staffers, and only Democratic lawmakers have expressed support for the effort. In a recent House hearing, Republican members dismissed the unionizing effort as a “solution in search of a problem” and an “impractical” one at that. But Democrats, who generally fund-raise and campaign on pro-worker platforms, are perhaps vulnerable to allegations of hypocrisy if they don’t support their own staff’s organizing. “Frankly, we are not, in many cases, walking the walk in terms of the way that staff are getting treated and paid and supported,” says Congresswoman Melanie Stansbury, a New Mexico Democrat, who supports the unionization effort.

But there are legitimate reasons lawmakers might be skeptical of a unionized Congress. The offices of Representatives and Senators don’t function like normal businesses that can raise wages and increase benefits according to market conditions; each office, instead, is provided a strict yearly allowance, which they use for most expenses, including mail, district travel, and paying aides. That model doesn’t leave much wiggle room to boost salaries. Each lawmaker’s office also operates independently, meaning that each must be unionized independently. A “unionized Congress” is, in reality, hundreds of discrete bargaining units.

CWU organizers say they aren’t intimidated by the significant hurdles ahead. With public support for labor unions reaching a nearly 60-year high and the Great Resignation reorganizing Americans’ priorities, now is the time to act, they say. Since congressional Democrats have failed thus far to advance any significant labor legislation to the President’s desk—including the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which would bolster union protections for private-sector workers, or Build Back Better, which included some PRO Act provisions—supporting the effort to unionize Congress offers lawmakers an opportunity to make good on their pro-labor campaign promises. If it can’t act to legislatively protect U.S. workers, says a member of the CWU, “then the next thing that Congress can do to help the labor movement is to look at their own workers.”

A tipping point

It’s no big secret in Washington that Hill staffers are poorly paid and overworked. It’s not uncommon to see aides working at the Capitol past midnight or chauffeuring their bosses to the airport before returning to a tiny, overcrowded D.C. apartment. But the past two years have brought those conditions into even sharper focus. Grueling, COVID-19-related working conditions combined with the terror of the Jan. 6 insurrection, galvanized a long-simmering desire for change. In the days and weeks after the attack, which forced lawmakers and their staffers to hide behind barricades or evacuate their offices, aides began reaching out to one another to discuss how to make their offices safer. Eventually, three young aides convened on a FaceTime call to talk about creating a formal union. One of them, a young woman who took the call in a Rayburn House Office Building bathroom stall to avoid eavesdroppers, remembers being so relieved to discover she was not alone that she cried after hanging up. “To be at a point today, where we’ve come from these dark moments is so exciting,” she says.

A year later, in early 2022, an Instagram account, @dear_white_staffers, which originated as a meme account bringing levity to the challenges of being a staffer of color in a predominantly white space, transformed into a Capitol Hill Gossip Girl of sorts: sharing anonymous, first-person accounts of lawmakers treating staff poorly to 80,000-plus followers and capturing the media spotlight. The posts, unaffiliated with the CWU organizing effort, were both hilarious and horrifying: multiple staffers claimed that they were required to “sign out” in order to leave their desks to use the restroom; another claimed their pay was docked to tend to their sick child, despite working ample unpaid overtime. On Feb. 3, reporter Pablo Manríquez, citing the account, asked Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi if she’d support a congressional union. When Pelosi said yes, CWU organizers seized the moment.

Read More: How to Make Congress Work Better for the American People

Until then, their work had been underground, conducted via encrypted text and clandestine meetings, but the night of Pelosi’s remarks, organizers stayed up until 3 a.m. drafting press releases and creating social media accounts. Within days, both Senate majority leader Chuck Schumer and White House press secretary Jen Psaki expressed support. “None of us thought that this would happen at the pace that it is,” says one organizer.

There are few useful roadmaps for what lies ahead. Starbucks workers’ successful push in the last year to individually unionize seven Starbucks-owned cafés offers some guidance on how staffers might go about collectively organizing hundreds of independent offices. Because they work for a private company, though, Starbucks workers’ have more flexibility in bargaining over benefits like health care options and tuition reimbursement.

Bernie Sanders’ staffers’ successful push, in 2019, to unionize the Senator’s 2020 presidential campaign is also instructive. Like Hill offices, political campaigns don’t operate like normal businesses, and form and dissipate along with their boss’s career. If a political candidate ends their candidacy, everyone is out of job. In May 2019, his staffers achieved, through both good-faith negotiations with management and pressure tactics by engaging with press—a first-of-its-kind ratified union contract agreement granting them defined salary bands and guaranteed time off, which, according to former campaign manager Faiz Shakir, ultimately made the campaign operate more efficiently.

Neither is a perfect analogy. Unlike Starbucks and campaign workers, Hill staffers would be barred by federal law from work stoppages and picketing if they were to successfully unionize their offices.

Supporting the entire institution

But Congress’s uniqueness is also what makes the effort so critical, organizers say. Low pay and grueling hours aren’t just dispiriting for individuals; they fuel the brain drain that has contributed to Congress’s crippling lack of institutional knowledge. Staffers are incentivized to “become the lobbyists that the next staffer who has no institutional expertise has to rely on,” says a CWU member. This cements government’s “built-in reliance on lobbyists” to navigate complex policy issues. In 2019, the average tenure for Capitol Hill staff was three years, according to liberal think tank New America; 43% of staff intend to pursue private-sector employment after their time on the Hill. The dual stresses of COVID-19 and Jan. 6, combined with other economic factors, likely exacerbated the rush to the exits. In 2021, House staffers left their jobs at the highest rate in at least two decades, according to data analyzed by LegiStorm, a platform that complies congressional data. Last year’s attrition rate was 55% higher than in 2020.

Demanding working conditions and meager wages also mean that staff jobs generally go to “people who are privileged,” says James Jones, an associate professor at Rutgers University and the author of the forthcoming book The Last Plantation: Racism in the Halls of Congress. A 2020 report from the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, a Washington-based think tank, found that 89% of top Senate aides—chiefs of staff, policy chiefs, and communications directors—are white. On the House side, 81% are white.

Read More: 40 Ways to Build a More Equitable America

That lack of racial diversity is bad for Congress’s ability to craft legislation on issues like criminal justice reform, home lending laws, and healthcare that take into account the unique circumstances of marginalized populations, Jones says. But it’s also bad for the rest of Washington, which relies on Congress “as a credentialing institution.” “You spend a few years on Capitol Hill, but that experience gives you a license to work in many other elite workplaces, like the White House or the Supreme Court,” Jones says. Early-career Hill roles paved the way for top political leaders Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell and Vice President Kamala Harris. In other words, organizers argue, making Congress a more decent place to work could pay dividends to American democracy.

“It’s difficult when the only people who can afford to work in Congress either have come from a place of privilege, end up marrying a lobbyist or are literally struggling to make ends meet,” says one of the CWU organizers.

Changing that dynamic is what brought the CWU organizers together in the first place. But they can’t do it on their own. They had to find a member of Congress willing to tie his or her name to the resolution in order to formally introduce it.

Uncharted territory

In the months before the Pelosi press conference, the CWU workers had identified Congressman Andy Levin as a candidate for the task. After Feb. 3, they began communicating with he and his team, via text and phone calls, about how to use the window of opportunity. “The staff came to me because they knew that I would understand that this isn’t about us,” Levin says, “and it isn’t about what headaches it might cause.”

Levin has been in this position before. As a student at Williams College in the early 1980s, amid a bizarre wave of streaking across college campuses, he organized a petition demanding that college administrators select a more labor-friendly manufacturer for graduation caps and gowns to avoid crossing the picket lines of the factory the college historically used. If the administration didn’t comply, Levin’s petition floated what he describes as a “cheeky” threat: the senior class would show up “disrobed” to the graduation ceremony. Levin’s goal was achieved. The school switched manufacturers—and Levin became a lifelong labor advocate, eventually working for SEIU, AFL-CIO and consulting Clinton-era labor Secretary Robert Reich.

It was no surprise, then, that Levin was the one to introduce the union resolution on behalf of the Congressional staffers on Feb. 9. But the pathway to a Congressional staffers’ union actually goes back 27 years, when Republican Senator Chuck Grassley introduced the 1995 Congressional Accountability Act (CAA). That legislation sought to extend similar workplace safety standards and labor rights individuals in other public and private sector jobs enjoy to Capitol employees. But before the union protections defined in the CAA could be extended to legislative staffers, the two chambers would have had to vote for final regulations issued by what is now called the The Office of Congressional Workplace Rights. Neither chamber moved to adopt the regulations, leaving them in limbo—until Levin introduced his resolution attempting to codify them last month.

Read More: Congress Isn’t Stuck in Political Gridlock. But That Doesn’t Mean It’s Working

Barriers remain. The resolution would need 217 votes to pass, but only 165 Democrats have signed onto the resolution as co-sponsors. CWU members are especially frustrated by the 55 House Democrats who voted to buttress unionization in the private sector via the PRO Act, but have so far not signed onto protections for their own staff.

And before it can even move out of the Committee on House Administration to the floor for a vote, there are technical issues that need to be resolved. The Office of Congressional Workplace Rights has identified a problem with the way Levin’s resolution is worded, says a source familiar with the committee’s deliberations. “Essentially, it does not do what it would purport to do,” the source says. “That needs to be fixed.” The source adds that a solution to the problem should be identified in “the next few weeks.”

In the Senate, things are even less rosy. Senator Sherrod Brown said he planned to introduce a Senate resolution after Levin’s House version, in order to extend the legal protections to Senate staffers, but he has not yet done so. Even if he did, it would have very little chance of passing the Senate’s 60-vote threshold. Democratic Senator Joe Manchin has expressed skepticism regarding the workability of a unionized Senate staff, and no Republican Senators have publicly endorsed the efforts.

But as the resolutions stall, the staffers’ ambitions have not. In March, Congress passed an appropriations bill increasing House members’ office allowances by 21%—the largest increase in the MRA appropriation since its authorization in 1996. CWU members have since advised several staffers on how to advocate for salary increases tied to the boost—a small victory, but one that gives purpose. “I feel proud to be a Hill staffer,” says one, “for the first time in a long time. Potentially ever.”

—With reporting by Mariah Espada/Washington

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Abby Vesoulis at abby.vesoulis@time.com