Though it is far from the only example of its work, Cure Violence is perhaps the most familiar anti-violence program in the country. Founded in 2000 in Chicago by Dr. Gary Slutkin, an epidemiologist who is often credited as among those who first conceived of violence interruption work in the 1990s, the program aims to treat violence like a disease. Its goal is to “interrupt” the spread of that disease by hiring people within the neighborhoods it operates in and using them to mediate violent conflicts.

In the years since, a number of cities have implemented or adapted Cure Violence’s strategies to address gun violence in their communities. But to what end? A review of the program’s rollout in St. Louis over the last 18 months raises some questions over the program’s effectiveness both in its own right and, crucially, at the expense of other strategies, adding fuel to a debate that has persisted for years within the violence prevention community and wider community advocacy networks.

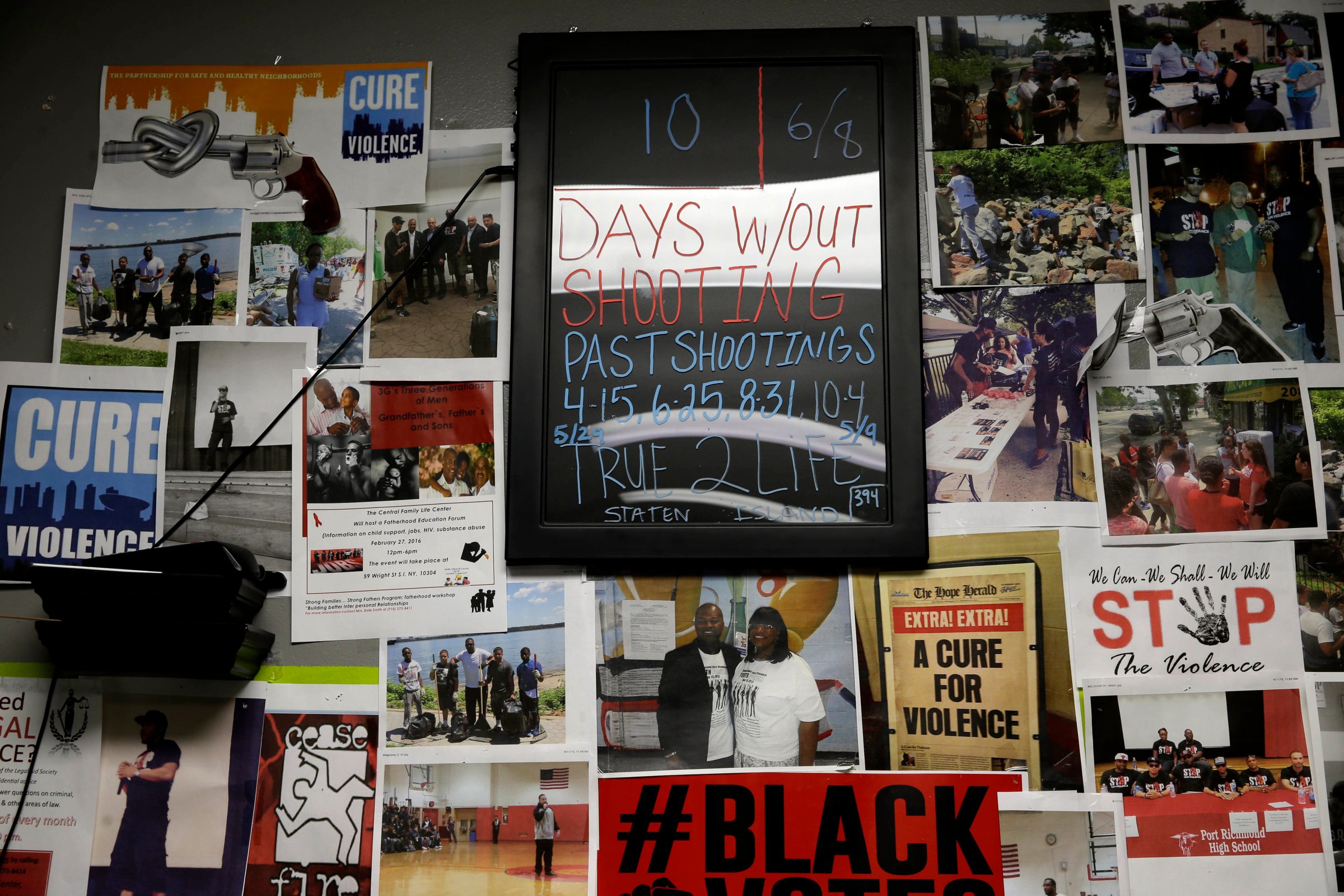

Read more: Much Like the Victims They Try to Help, Gun Violence Prevention Workers Have Scars

In 2019, St. Louis invested $7 million to fund the implementation of Cure Violence—a fairly expensive buy-in when compared to other similar types of community-led initiatives. The program was officially launched in June 2020, a noteworthy period as the U.S. was in the early stages of what would be a significant surge in gun violence throughout the U.S. The summer also marked a nationwide reckoning over racial injustice and police brutality, with protests in cities across the U.S.—St. Louis among them—following the murder of George Floyd.

Like many other cities, 2020 was a deadly year for St. Louis—it marked the city’s highest murder rate in half a century. However, things improved drastically in 2021, with a huge drop in shootings and homicides.

It’s unclear what exactly led to the decrease, but a fair hope if not expectation among stakeholders, whether city leaders or local residents, would be that Cure Violence played some role. However, an analysis from St. Louis-based criminologist Rick Rosenfeld suggests that may not be the case.

“If Cure Violence reduced homicides and gun assaults and contributed to the overall reductions in these offenses between 2020 and 2021,” Rosenfeld tells TIME, “we should observe greater reductions in the Cure Violence neighborhoods than in the comparison neighborhoods.”

His analysis set out to determine whether that has been the case. More specifically, it focused on ‘comparable’ neighborhoods to avoid its results being skewed by demographic and socio-cultural divides apparent in the city.

“A staple of good evaluation research is to compare people or places receiving a ‘treatment’ such as Cure Violence with similar people or places that [are] not. All neighborhoods on the north side of the city… were selected for comparison with the three north side Cure Violence neighborhoods,” the analysis explains, with the exception of those “immediately adjacent” to avoid potential overlap.

And across the board, Rosenfeld found that homicides and gun assaults did not decrease in the neighborhoods Cure Violence had rolled its program out in any more than it did in neighborhoods that didn’t have the program.

“I want to make it clear that this is a one-year assessment. It’s possible that these kinds of programs take a long time to show effects—but then it’s incumbent on program directors to tell us when the program will be ready for rigorous evaluations.” Rosenfeld continues. Cure Violence does not currently provide such timelines or timeframes in which it expects its work to foster change.

“The findings are not a big surprise,” Paul Carrillo, community violence initiative director at the Giffords Law Center, tells TIME. “It shouldn’t be seen as an indictment on the program though. Since they focus on the most dangerous areas of St. Louis, that in of itself is going to be difficult to show results early.”

Charles Ransford, Cure Violence’s director of science and policy, tells TIME that the analysis in St. Louis doesn’t accurately assess the program, arguing that Rosenfeld’s neighborhood-based comparison method is flawed.

“He’s looking at this large neighborhood set of data when we’re working in a small catchment area—10-by-10 blocks,” Ransford says. “He’s holding the Cure Violence program in that area responsible for areas that we’re not even funded to work in.”

Read more: The Complex Dynamic Between ‘Violence Interrupters’ and Police

This is not the first analysis of the Cure Violence program to yield mixed results. A 2015 review of the program in Pittsburgh (which ran from 2004-2012) published by the Annual Review of Public Health did not find a significant reduction in homicides in the target areas. Furthermore, the review said, “the program appeared to be associated with an increase in rates of monthly aggravated assaults and gun assaults in the Northside.”

The review also pointed to mixed results from the program’s implementation in certain Baltimore and Chicago neighborhoods. And a 2020 report by John Jay College on alternatives to policing notes that the work of outreach workers and violence interrupters is “promising but mixed.”

According to Ransford, the program in Pittsburgh didn’t actually follow the Cure Violence model; in parts of Baltimore and Chicago, he continues, the program was not being implemented properly. And data compiled by Cure Violence of other independent studies done on the program illustrates it’s been effective in a variety of locations over the past decade. Cities New York and Richmond, Calif. have seen more positive results with the program.

“We know this approach can work, the evidence is pretty conclusive. When it’s implemented correctly, the program gets results,” Ransford says.

However, whether perceived or otherwise, these issues and inconsistencies exemplify why addressing gun violence is so tricky. Activists, community leaders, experts and politicians have made it clear that there isn’t one solution to this problem. St. Louis Mayor Tishaura Jones said in January that Cure Violence isn’t a “silver bullet,” but rather one piece to a “larger holistic approach to address violent crime.”

“There is no one model. It’s one important strategy as part of a comprehensive approach,” Carrillo says. “The problem is a lot of cities don’t have a comprehensive approach—they struggle with coordinating all the different strategies.”

Carrillo says that assessing—and addressing—any given city or neighborhood’s individual struggles is key; just because a program or initiative works well in one community doesn’t mean that it’ll work the same exact way in another. If anything, the through-line is that what community leaders ask for should be prioritized.

“There are a lot of layers. Which political party is running the city or the county? In a lot of areas, you have to find people out of nowhere,” Carrillo adds. “It takes time. It has to be organic.”

Beyond that, broader questions remain: once someone is stopped from committing a crime or act of violence, for example, what’s next? This is where a commitment to social services, schools, housing and infrastructure in neighborhoods struggling with violence and crime comes into play. And given the cost of Cure Violence, Rosenfeld believes that cities should not ignore other less expensive programs that can address gun violence or support adjacent community programs.

Even still, Rosenfeld says his analysis is not meant as an indictment of Cure Violence. ” I do not advocate that Cure Violence be abandoned based on my research,” he tells TIME. “What I do advocate is that it be thoroughly evaluated before it is expanded.”

The Biden administration has pledged millions of dollars for community violence intervention as part of the American Rescue plan and other legislation—much of that money is expected to go to programs like Cure Violence. But many activists hope that’s not at the expense of other community projects and causes.

“They’re trying to make sure that [the investment is] community-led,” Carrillo says of the administration’s intent. “Let’s hope it is.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Josiah Bates at josiah.bates@time.com