A few years ago, I began to look every so often at the two Census reports where my one known ancestor from Maryland appears: 1870 and 1880. I’m always hoping to discover something I missed—about myself, about my past. Every gaze is a moment of wonder and frustration. There she is, twice. In 1870, she is Easter Lowe. Born in Maryland in 1769, 101 years old, Black. In 1880, she is Esther Watkins, born in Georgia in 1789, 91 years old, widowed, Black. Both improbable and extraordinary. In rare, lighter moments, it makes me think of Mark Twain’s humorous story about George Washington’s mammy, Joice Heth, who in newspaper report after newspaper report kept getting older until her age rivaled Methuselah’s (as we say it).

Whereas Twain noted a sentimentalism toward the old plantation darky that verged on the ridiculous, my own ancestor’s imprecision is a bitter wound. And I have some awe, too, at what must have been a daunting attempt to name her age. “How to place her in history?” somebody speculated. Most of the time I feel a combination of reverence and sadness. It is unlikely I will ever know what happened or when exactly she was born. I can guess. The ages are probably wrong but could be right. There were some enslaved people who lived to extraordinarily old ages. Perhaps she was sold from Maryland down the river. Maybe from a man named Lowe to a man named Watkins who wanted to settle the Georgia frontier. And later, as Mississippi was carved out of Georgia and Alabama out of Mississippi, she, a woman who at least by one account was born before the nation was a nation, was still living, an elderly freedwoman in Madison County, Ala.

Even if I doubt her age, there is the AncestryDNA evidence that says I descend from people who lived in early 18th century Virginia. Inexact borders aside, what holds is this: we came before America was America. This woman who bore the name either of my favorite biblical queen or my favorite holiday was here, not as an accomplice to the settler colony, but as the victim of its displacement and captivity. She was a witness to the very exclusions that laid the foundation for the creation of a national identity. It is a remarkable status.

I wanted to travel to Maryland, to see something about my ancestral beginnings, but I had no idea of where to go. I ultimately chose to go to Annapolis, the capital. It is a precious town. One that is self-consciously old, like it was manicured that way. I wasn’t sure exactly what I was looking for there at first. I just went.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a Deep Southerner who would ever call Maryland or Washington, D.C., the South. Even the storied history of enslaved people from Maryland doesn’t keep it from seeming Northern. Not Alethia Browning Tanner, an enslaved woman who sold vegetables directly outside of the White House. Not even Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, heroes of history who were both held captive in Maryland. I still am reticent to call the mid-Atlantic South the South. And yet I have learned in the course of my travels that there are “Souths,” plural as much as singular, despite my Deep South bias. I know that while the South is a determined thing, it is also a shifting and varied one. Re-declared many times as a fact, it echoes far beyond its moving borders.

There was a particular place I had learned about as I was digging around in stories of Maryland, and I wanted to get to it in order to figure out what I was looking for here. I’d read that there was a pub where founding fathers used to drink, carouse and sell Black people. And it is still open. My phone GPS went topsy-turvy for a little bit, but eventually I found the tavern.

I stepped inside, hoping to feel something mystical. Nothing. It was dimly lit and fairly inglorious. I sat awkwardly in a black-painted wood chair, alone and facing a young family with a little girl in a high chair, with the bar behind me. I ate fish fried in a thick batter. The pocket of heat under the skin was tongue-burning but increased the sweetness of the flesh. I drank cranberry juice with ice cubes too large to chew. I looked at the fixtures; I looked at the floor. It was disorientingly dark.

As historians of slavery have noted, our images of auction blocks are more theatrical than the reality often was. Regular places were sites of the trade in people. The everydayness of disaster was a feature of slave society. We might be inclined to look for somewhere to place a memorial or an altar to the past that we can treat as particularly hallowed ground. But the truth is that this mundane place where I was served cranberry juice and fish by a young White man with flopping brown hair and an eager smile is exactly where my foreparents might have been wrenched away from everything they loved. Matter-of-fact, like that. When I went outside again, the sunlight felt like it was about to blind me.

More from TIME

Next, I decided, I’d visit two historic museum homes of which Annapolis boasts. The first was under construction. I made it to the second just in time for a docent-led tour. It began inauspiciously. The guide was lovely, but the moment the phrase “Those nasty Indians tried to fight us, and we had to fight back” came out of her mouth, chill bumps raised on my forearms. Well, I thought, this might be some good material. Not a moment later a manager ran up to me: “I heard you’re working on a book!” I hadn’t intended to be treated as though I was there on an official visit. But I accepted her graciousness. She told me that I could take a hard hat tour of the building that was under construction and gave me her card, which I promptly lost. And then she followed up, explaining, “We are trying to tell the history more thoroughly. That house is where we found artifacts that relate to the history of enslaved people in Maryland.” Her words were offered gingerly and with sensitivity. I didn’t inquire further. I wasn’t interested in making an indictment or issuing praise. I was just trying to see how the back-then is inside the now.

We walked through rooms restored with great detail. Historic preservation is a painstaking business, especially when it comes to paint colors and fabrics. It is a matter of samples and formulas, mailing them back and forth and cross-referencing up the wazoo and things being not quite right until they are iterated to perfection. Unexpectedly, the docent turned and looked at me wide-eyed. “I hate to tell you. But I have to talk about”—and she whispered the word—“slavery.” I shrugged. “Well, yes,” she said, “it did happen.” “Yes. It did,” I replied.

Read more: The 21 Most Anticipated Books of 2022

My companions on the tour were a lovely couple, older and White. They were deeply interested in history and preservation and traveled frequently to experience both. The woman, a Kentuckian with a thin gray bowl haircut and a smile so earnest it looked like it belonged on a 12-year-old, struggled a bit. These old homes are hard to move about in if you have a physical disability. Before we made it to the basement, my bowl-cut companion needed to sit. The docent led her and her husband to the garden. I walked down a set of stairs and joined in on another tour.

A young White couple recently graduated from Georgetown University was listening. They were smartly but casually dressed, with studiously respectful expressions on their faces. Standing in the kitchen, this docent told us that the enslaved woman in charge of the cooking slept there, on the floor in front of the hearth. It was freezing cold in the winter and sweltering in the summer. On a kitchen table, which, compared to the elaborately set dining table upstairs, was rough-hewn, a feast awaited delivery. I wondered who brought upstairs the sumptuous meals replicated in plastic.

Then the guide said something that stuck in my craw. Slave cooks had to possess a great deal of knowledge. They had to understand science and math, even though they were illiterate. They had to keep track of proportion, the distribution of heat and the ingredients to every meal they made. The docent pointed to a device, gleaming metal with a pulley, that was used to turn meat in order for it to be fully cooked; though it aided the task, cooking still required rapt attention. Maybe because I have spent my entire adult life studying and researching with the control and aid of books, archives and computers, the colonization of this Black woman’s mind hit me hard. I have long known that each purchase of a slave was an investment. The feeding and clothing of one was as well. The task was to keep them alive enough to work and procreate, and cheap enough to yield the highest profit margin. Also, they were supposed to be abused enough to terrorize them out of retaliation. It has often been noted that slaves were denied knowledge as a way to keep them docile. But some, like the builders, the blacksmiths, the plantation botanists and the cooks, were required to hold vast knowledge and steady it in their minds and memory because pen and paper were denied.

The life task of the enslaved person was to stay alive and where possible love and find some joy. I imagined this cook lying on this intact ground, shivering, sweltering, alone and knowing. An archive in her head, her name left on no ledger, no wall in this house. There is no recording of the precise color of her flesh or apron. I imagined her smacked for an error or patronizingly praised, and aching. Eventually arthritic, smiled at for making the loveliest cakes, until, like her birth, her death came and went without public notice. Tears welled up in my eyes, and I am somewhat embarrassed to say that I felt a momentary relief that if my ancestor, Easter or Esther, worked here, I didn’t know it.

I wonder if Easter or Esther looked at the ships, like Frederick Douglass did, longingly. I wonder if she dreamed of boarding one and finding another place to be or returning to her mother’s home. Easter Lowe, or Esther Watkins, is my ancestor and my muse. I set her alongside the documented stories of Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass. Home is such a jealously guarded concept in my life, so specific. I don’t know how it was in hers. Did slavery make home always somewhere else? In Barracoon, Zora Neale Hurston made clear that “home” for the last Africans brought here on slave ships was different than it was for African Americans, for whom this was the only place they knew. Home was vexed but here. For the Africans, it remained out there. Without knowing how close or far Africa was in Easter’s life, my thoughts could not even be convincingly speculative.

When it comes to memory and slavery, there are people who center their concern on the gaps and absences. They dwell on the grief of silences. And there are people who every day are fitting puzzle pieces together to find as much truth and detail as possible. Both are essential.

We, descendants of the incomplete puzzle, know a good deal about dwelling in rough, negotiated spaces. Trapping places where intimacy existed despite the fact that law did not recognize its sanctity. Places where life and death and woundedness and love all persisted. But did our ancestors truly feel at home? (Do we?) Was home some affect in the ether, hard to hold, or a future perfect tension, imagined as part of some freedom to come? This word that I hold in my mouth, ever and always meaning the state where I was born—home is not something I am sure had meaning before freedom.

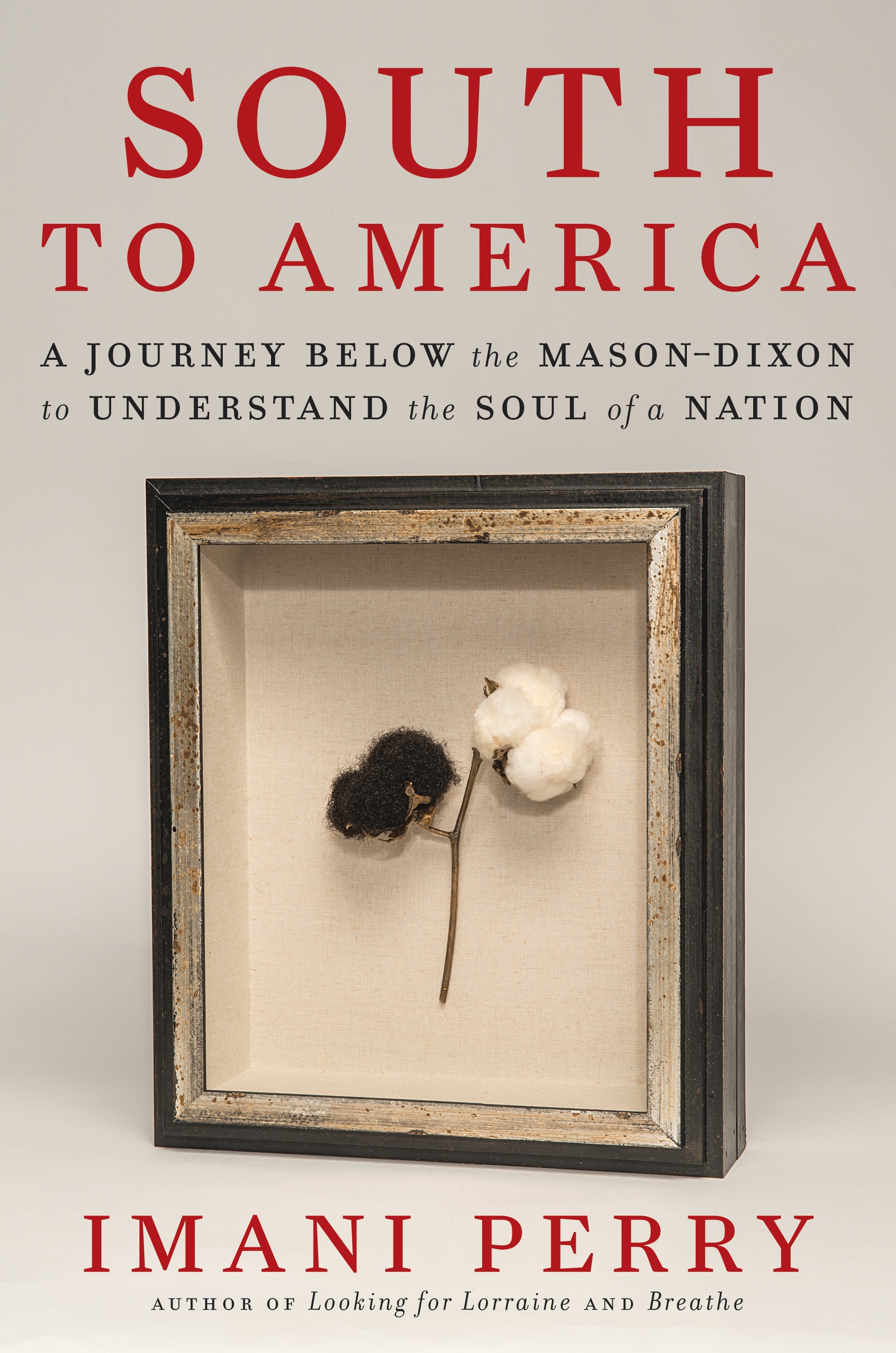

Adapted from South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation by Imani Perry, available Jan. 25 from Ecco/HarperCollins.

Correction, Jan. 25: The original version of this story misspelled the first name of an enslaved woman who sold vegetables outside the White House. She was Alethia Browning Tanner, not Althea.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com