On Oct. 5, 1968, chaos broke out in the streets of Derry, Northern Ireland. As a civil rights parade wound through the streets, the police—or Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)—blocked the protesters’ route, surrounding them. Forming two intimidating lines on either side, the RUC baton-charged protesters. Images of the violence were broadcast into homes around the globe. Writing later that month for the BBC magazine, The Listener, the poet Seamus Heaney declared the moment a “watershed in the political life of Northern Ireland.” After this, Heaney wrote, there could be no more “shades of grey.”

I thought of Heaney’s words as I watched Kenneth Branagh’s heavily autobiographical film Belfast, which releases in the U.S. on Nov. 12 following a successful run at fall film festivals. The film opens with glorious vistas of contemporary Belfast in full color, from its opening shot of the sunflower yellow of the Harland and Wolff cranes to the lilac sea-blues of the Titanic museum, and aerial footage of the city surrounded by the verdant green of Cave Hill, nestled in the crook of Belfast Loch. A version of Van Morrison’s “Coming Down to Joy” soundtracks these images. We only get a glancing look at this highlight of the city’s tourist reel before we soon lose the pigment for black and white Belfast of mid-August 1969.

At first, the movie presents this moment in the city’s history as a more innocent time. We see the lead character, a young boy named Buddy (Jude Hill), playing with his friends in their terraced street in a “mixed” area of north Belfast, where both of Northern Ireland’s dominant two communities live alongside each other peacefully. These “two communities” have their roots in centuries of entanglements between Ireland and Britain, an often-fraught relationship exacerbated exponentially by the messy, violent partition of Ireland in 1921. The “two sides” are the nationalist or republican community, who are usually (but not always) Catholic and identify as Irish; and the unionist or loyalist community, largely Protestant, who identify as British and wish to remain in “the union” that forms the United Kingdom of Northern Ireland and Great Britain.

In Branagh’s Belfast, this peace between communities doesn’t last for long. Minutes into the film, a wide-eyed Buddy is confronted with a riotous, swarming masked mob brandishing torches and homemade weapons, screaming chants of “Catholics Out!” It’s a pacey opening scene. But, for all the exposition-heavy dialogue that follows (“You’re as welcome here as anyone, Paddy”) and the occasional splices of TV or radio news playing in the background, audiences unfamiliar with the Northern Ireland conflict might be left as disoriented and confused as Buddy is.

A summer of escalating violence

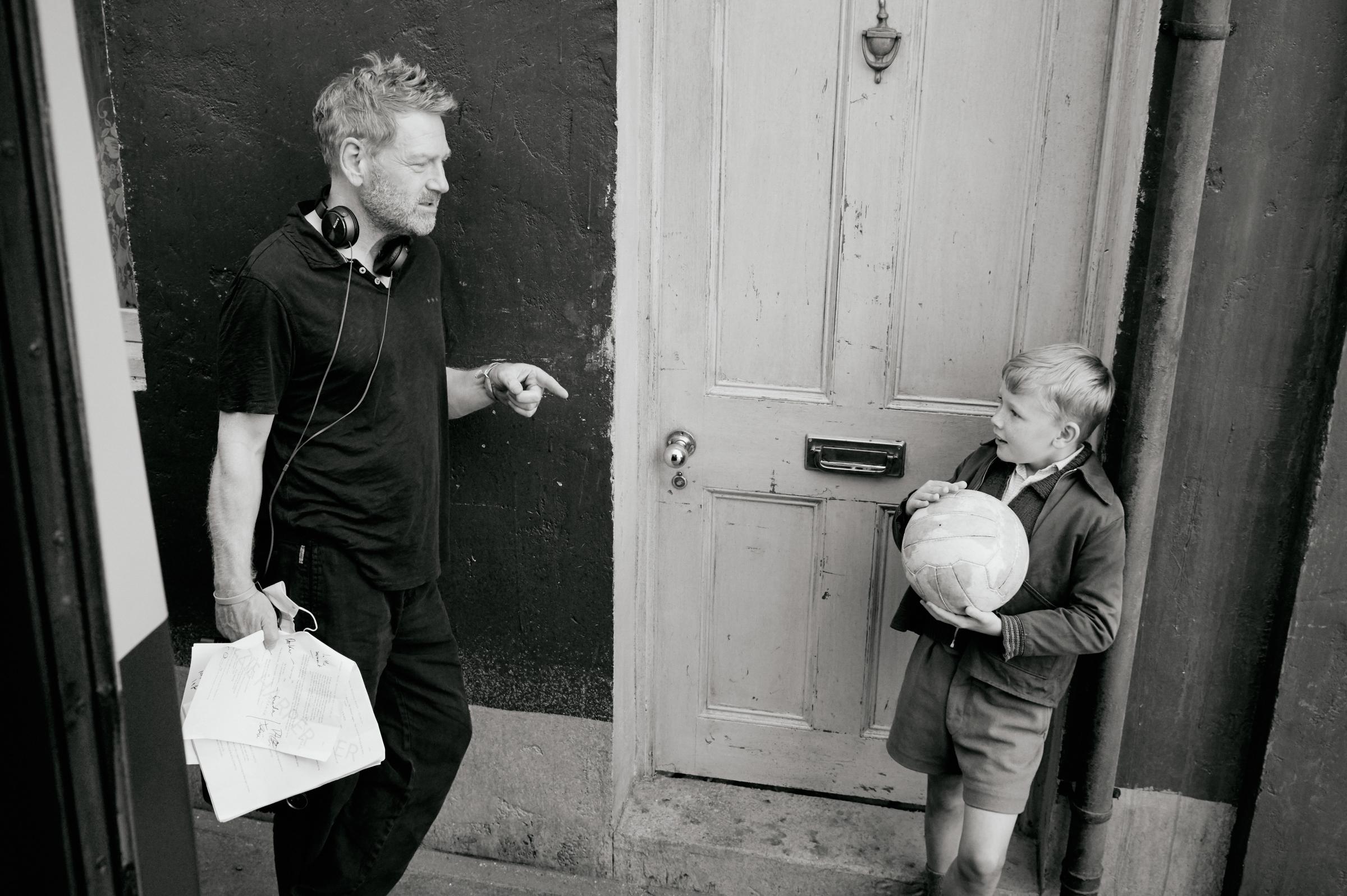

The riots that Buddy witnesses did in fact happen in Belfast in August 1969, and Branagh’s film draws strongly on his own experience as a child growing up at 96 Mountcollyer Street in north Belfast. The writer-director, whose family was Protestant, has said that he hid under the dining room table, much like Buddy and his older brother’s mother instructs them to do, as a group of Protestants from the Shankill Road came to their street with the aim of intimidating Catholics out of their homes.

The riots came as part of a week of violence across Northern Ireland. On Aug. 12, in Derry, a parade by the Protestant Apprentice Boys was followed by fighting between the RUC and the residents of the Bogside, a Catholic nationalist area of the city. The British Army was deployed to quell what is now known as the “Battle of the Bogside.” In Belfast, and across the North, nationalists called for protests in response; amid the escalating tensions and paranoia across the city, violent riots soon broke out.

Until this point, parts of Belfast had still been relatively mixed, with Catholics and Protestants often living side by side. As the violence escalated, many families fled their homes in terror; scores of houses were burnt down, like those in Conway and Bombay Streets in west Belfast. This was displacement on a significant scale: thousands of people left their homes, with many Catholic refugees fleeing south across the border in an echo of the unrest following Partition. This decision—to stay or to leave and start a new life in England—is the central tension facing Buddy’s family in the film, with his parents, whom he calls Ma (Catriona Balfe) and Da (Jamie Dornan), in a stalemate.

Makeshift barricades went up across the city, as depicted in Belfast. There was an unease among the Catholic population that the police would not protect them and their homes because the RUC was overwhelmingly unionist and Protestant. Branagh’s film gives voice to this fear of abandonment, too, when one of the characters declares, “The Police won’t protect us, we have to do it ourselves.” While Buddy’s family is Protestant, his father faces threats of violence from another Protestant character for his attempts to remain neutral—his insistence on remaining in the “shades of grey.”

As Branagh’s film also dramatizes, the British Army was sent into the streets of Belfast that month. Initially deployed as a temporary measure to protect Catholics from violence, the British Army’s “Operation Banner” would maintain a presence that became tense in Northern Ireland from 1969 until 2007, nearly a decade after the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement brokered a fragile peace.

Part of a global movement for civil rights

These riots of 1969 didn’t come out of nowhere: tensions had been building for years. In Belfast, Buddy’s Da lays the blame for the conflict at the feet of “Bloody Religion;” this is an oversimplification of a highly complex political situation. The violence of Partition had established a statelet with a Protestant majority; unionist interests were maintained through repressive tactics to the detriment of the Catholic minority. Being Catholic didn’t just mean that you held different religious beliefs: it meant you were significantly more likely to suffer unfair employment practices, inequitable housing distribution and be disenfranchised due to gerrymandering that favored unionists in elections.

Unrest had been especially potent following the establishment of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) in 1967. The NICRA was founded in an effort to address state discrimination against the Catholic minority and members came from a variety of political and religious backgrounds. And, of course, Ireland didn’t exist in a vacuum. Social activism, civil rights mobilization and mass protest were a globally defining feature of the late 1960s.

This Northern Irish civil rights movement drew heavily on the U.S.-based African-American civil rights movement of the 1960s for inspiration. In 1969, Irish politician and civil rights campaigner Bernadette Devlin was given the key to New York City; in 1970, on his visit to the United States, fellow Irish activist Eamonn McCann gave this key to the Black Panthers “as a gesture of solidarity with the Black liberation and revolutionary socialist movements in America.”

Branagh’s film gives us glimpses of this Belfast, too. It’s a Belfast that is much more diverse than viewers might expect, and one that complicates the idea that Belfast’s social fabric consists only of the binary “two communities.” Buddy’s schoolteacher is played by Irish-Nigerian actor Vanessa Ifediora, and there are numerous South Asian families living in north Belfast, including Mr Singh, who runs their local corner shop, and Granny’s (Judi Dench) Indian neighbor.

The Belfast writer Glenn Patterson has stated that “Belfast in the mid-1960s is curiously a very outward looking place.” In his novel The International (1999), about a barman in Belfast’s International Hotel in 1967, Patterson reaches back to a moment just before violence engulfed Northern Ireland. Like Branagh’s Belfast, returning to this time of suspended animation before the horror of the Troubles is a powerful way to retell the history of the conflict. It allows Branagh, who emigrated to England with his parents in 1970, to indulge in the romantic nostalgia of his own memory, and there is something highly artificial in the stylized aesthetic of the film. The carefully composed scenes remind viewers of the theater or old Hollywood, both of which, during a few scenes when the family enjoys a cultural outing together, puncture the narrative with bursts of color.

The child’s perspective as a storytelling device

But this return to an earlier Belfast does more than this. Telling audiences about how close these Belfast communities were, as neighbors chat on doorsteps and run through each other’s houses, makes plain how terrifying—and heartbreaking—the looming civil war will be. An amusing scene where Buddy and his friend, Moira (Lara McDonnell), discuss whether their names reveal their religious identity makes light of what would come. To return to Heaney once more, his caution that you must be “expertly civil-tongued with civil neighbours” rings heavy here. Branagh’s vision of such friendly coexistence foreshadows the horrifying intimacy of the impending conflict marked, Heaney writes, by “neighbourly murder.”

There’s also something painfully resonant about the film’s focus on the North through the eyes of a young child, even if Branagh runs the risk of simplifying or decontextualizing the very real history against which the story of Belfast is set. The Irish boyhood narrative has some serious literary clout to it too, like James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916)—to which Branagh’s film makes some decided nods, notably through the lengthy sermon from Buddy’s Protestant minister (in contrast to Joyce’s Catholic priest) about the horrors of hell awaiting sinners.

Using a child’s perspective to frame narratives about the North is common, too, as readers or viewers gain awareness and understanding of the conflict as the lead character does. Seamus Deane’s autobiographical novel Reading in the Dark (1996) springs to mind here, as does Lucy Caldwell’s novel Where They Were Missed (2006). Caldwell’s work is part of a growing body of fiction insisting on the importance of the Irish girlhood; Lisa McGee’s irreverent TV series Derry Girls is another joyful example.

Some of the drama of Belfast rests on the all too real fears of Buddy’s parents that their teenage son, Will, might be pressured into joining a loyalist gang. Children did become co-opted into various paramilitary organizations during the conflict. They were also casualties, too, as the harrowing ground of Freya McClements and Joe Duffy’s Children of the Troubles: The Untold Story of the Children Killed in the Northern Ireland Conflict makes so painfully clear.

A subtle—and contemporary—politics

Though Branagh’s film looks to be on solid footing heading into a long awards season, its saccharine charm won’t please everyone. Some reviewers have been quick to suggest it is apolitical—presumably because there are no men in suits debating things; no explicit references to paramilitary organisations; no discussion about “union,” either Irish or British. Belfast might not be Political in the way we demand of material about the Northern Ireland conflict, but it has its own politics, despite its simplified retelling of the conflict’s tensions. It’s the politics of the everyday, the personal and the ordinary. In small, subtle ways, Branagh’s film shows how homes, families and lives were lost and irrevocably changed by the conflict. Dustbin lids become makeshift shields; milk bottles become petrol bombs; laundry detergent is the centrepiece of a riot; doors close on relatives that would not open again.

For those who live in Northern Ireland, the simple facts of daily life are political. You can see this in the endless debate about what to call the six county statelet. Branagh’s film gets its release in the same year as the centenary of the Partition of Ireland, marking 100 years of a divided island. People who live in the North live with shades of gray, despite the fact that our political system operates on a consociational model which insists on binary thinking. This means all political decisions come back down to the black and white of Catholic/Protestant, nationalist/unionist.

The night I watched Belfast, a protest, ostensibly about dissatisfaction with the new Brexit protocol, broke out in Lanark Way, an interface area between communities in west Belfast. Alongside one of Belfast’s euphemistically named “Peace Walls,” loyalist youths threw missiles and fireworks at the police. The police made two arrests: both were boys, one 12, the other 15. Branagh’s black and white ode to a disappeared Belfast might play to most audiences as a historical drama. But as Northern Ireland hits the headlines again, for all the wrong reasons, Belfast might be more of a contemporary story than reminiscence on the long lost past.

Dr Alison Garden is a writer and academic based at Queen’s University Belfast, and the author of The Literary Afterlives of Roger Casement, 1899-2016 (2020). She is currently writing a book about love, mixed marriage and the Northern Ireland Conflict. She tweets at @NotSecretGarden and you can learn more about her work here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com