When Dr. Anthony Fauci arrived at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. for his first White House press briefing under the new Biden Administration, he could see things would be different.

It was the day after the Inauguration, and President Joe Biden was eager to get the country’s COVID-19 response back on track. Five minutes before he addressed the public, Fauci spoke with the new President. “He said, ‘I want you to just go and tell the science, explain to people that if we make mistakes, we’re going to fix the mistakes and we’re not going to dwell on the mistakes. Let science be communicated to the public.’”

Not such a radical position, but it was a lifeline for Fauci, who had become renowned as a target of the ire of President Trump and his supporters—mostly just for being an unwavering advocate for science and the facts. Jen Psaki, the new White House press secretary, asked, “‘O.K., what do you want to talk about, and how long do you want to be up there?'” says Fauci. And that was it.

“I said what I wanted to say. She didn’t check with the President or prompt me about what I was going to do. I just did it,” says Fauci. “It was a really good feeling, because it was really showing that science is going to rule.”

That rule has produced results. Biden pledged to administer 100 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine in his first 100 days in office; an invigorated, combined federal and state effort achieved that goal in 58, leading to a new target of 200 million doses, which was also met a week ahead of schedule and led to the latest sprint to vaccinate 70% of American adults with at least one dose by the Fourth of July. Cases are still higher than they should be, at around 30,000 new infections a day on average, but are starting to come down as more people get vaccinated.

Nearly two-thirds of Americans now approve of Biden’s handling of the pandemic, according to an ABC News-Ipsos poll. As the Biden team’s chief medical adviser, much of the credit goes to Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)—Fauci’s advice has been a part of every COVID-19-related decision made by the Biden Administration, beginning even before Biden took office, when the then-President-elect asked Fauci about requiring masks on all federal properties for 100 days in an effort to hold back the surge of new infections last winter. Every day since, Fauci has been asked about everything from whether the second dose of vaccines can be safely delayed, as the U.K. decided to do in January, to whether vaccines are still providing enough protection against new variants. That wasn’t the case during most of Fauci’s tenure on the White House Coronavirus Task Force under Trump. “Having been on the playing field, as it were, during both administrations,” says Fauci, ”having the ear of [this] President is manifestly totally different than what it was before.”

For scientists, truth is a given. It may come in different forms—as raw data churned out from a computer model, tables of statistics from a clinical trial of a new drug, or handwritten data scrawled in a lab notebook validating a new theory. But at their core, all scientific tools are rooted in objective and immutable facts. And throughout 2020, just when we needed it most, scientific truth was under fire as never before.

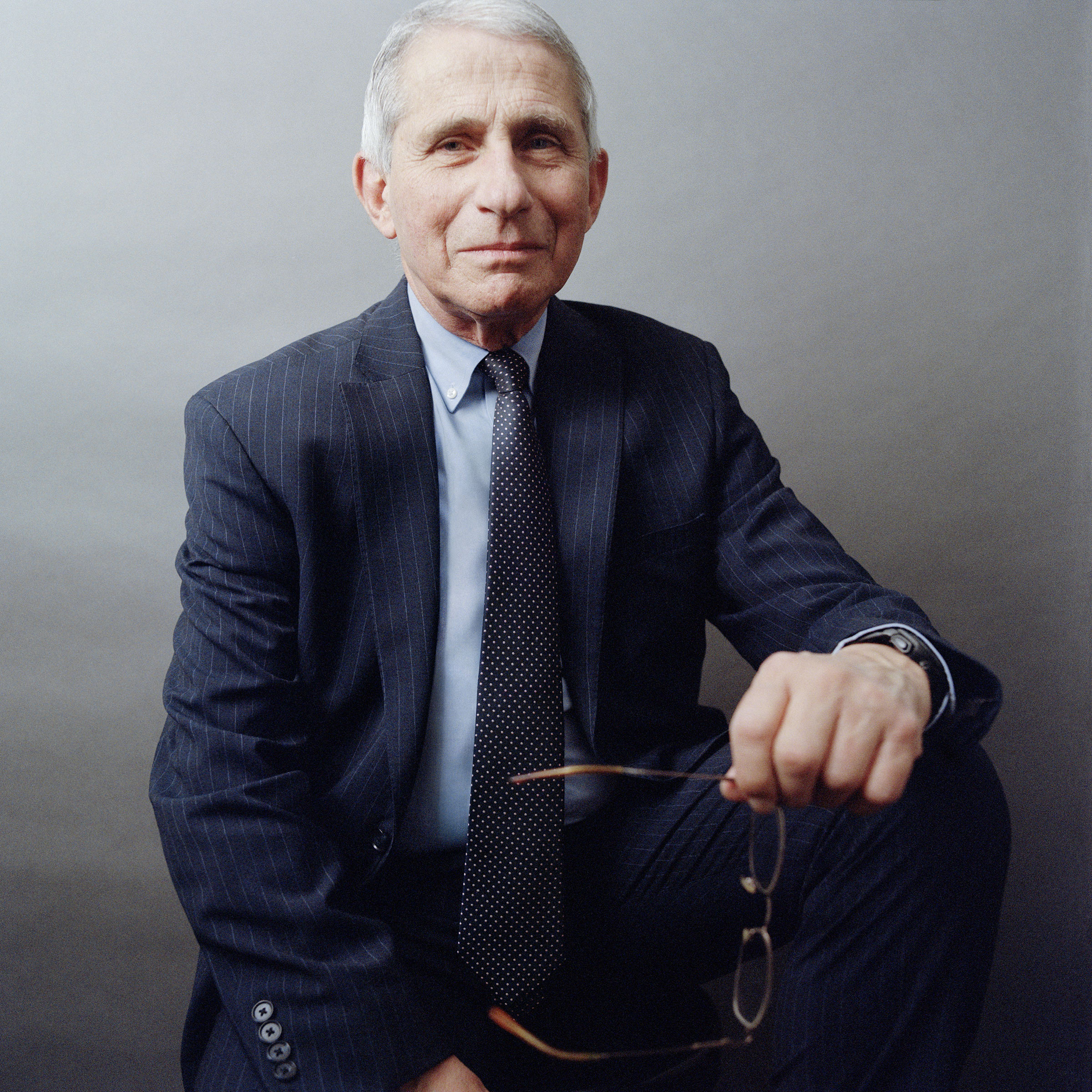

Defending that truth fell on the slight but sturdy shoulders of a fast-talking career civil servant with an unmistakable Brooklyn accent. For Fauci, sharing science is an integral part of practicing it; he believes the power of science is tied to its accessibility. When he became the voice and symbol of scientific integrity in a world turned upside down by an invisible virus, Fauci conducted a master class in scientific diplomacy, and invited the world to watch. We witnessed his live demonstrations on how to stay true to the facts despite the disruptive and often vindictive interventions of a President refusing to acknowledge the gravity of COVID-19. “Tony Fauci is a remarkably effective spokesperson for the truth,” says his boss, Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health.

For those who know him, even if only by reputation, Fauci’s appointment to the White House Coronavirus Task Force at the end of January 2020 was a beacon of reassurance through what ultimately became a dark and disturbing year. The entire U.S. public-health system—including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which normally lead the world in actions and advice on virus control—was largely sidelined as Trump systematically dismissed science in favor of political grandstanding. Week after week, Trump commandeered pandemic press briefings, downplayed the extent of the disease on social media, painted a rosier-than-reality picture of the U.S. response and mused on unproven and even dangerous “treatments,” from hydroxychloroquine to sunlight and bleach. Fauci took every opportunity he could find to provide a different voice, even as his own was turning raspier from the constant media appearances, press briefings and private meetings with Administration health officials to explain, educate and share what scientists knew and what they didn’t know about the viral threat.

Through contradictions, confrontations and even personal insults from Trump, Fauci refused to engage, focusing instead on the facts. And even with a new President, the attacks on him have continued. Republican members of Congress like Senator Rand Paul and Representative Jim Jordan have accused Fauci of engaging in “theater” and of quashing civil liberties by supporting public-health measures like mask-wearing in public. When he can get a word in edgewise, Fauci sticks to his message that everything the government is recommending is scientifically justified, but it’s often a struggle. “You don’t really have a conversation with Senator Paul,” he says. “In one interchange, he was speaking at me, through me and under me and making statements mostly based on incomplete data or selected, cherry-picked data.”

Where others might have stepped down, or at least considered it, Fauci never thought twice. “It’s kind of like General Patton during World War II saying, ‘I’m tired of this, I’m going to walk away.’ Your entire life you trained as a general to lead an army in a big war. It doesn’t matter what happens to you—you’re not going to walk away from it,” he said during one of several interviews conducted with TIME over the course of the past year. “You train as an infectious-disease person and you’re involved in public health like I am, if there is one challenge in your life you cannot walk away from, it is the most impactful pandemic in the last 102 years.”

“People have asked me over the years—multiple times—‘Tony, what keeps you up at night? What’s your worst-case scenario?’”

It’s nine months into the pandemic, and Fauci is sitting in a conference room in Building 31 on the National Institutes of Health (NIH) campus in Bethesda, Md., in front of the blue backdrop boasting the NIH-NIAID logos that has become a familiar site on his numerous virtual briefings and interviews. “We are living right now through my worst-case scenario.”

Because of the pandemic, most of the staff at the NIAID, which Fauci has directed for 36 years, is working remotely. Fauci conducts almost all his briefings that way, which has the added benefit of allowing him to squeeze in more opportunities to communicate with other public-health experts and the public since he’s not traveling from in-person meeting to in-person meeting. Since January, he has represented the scientific community in press briefings on the pandemic response three times a week, along with Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the newly appointed CDC director; Andy Slavitt, the White House senior adviser on the COVID-19 response; and Jeff Zients, the White House coronavirus response coordinator. The regular briefings are Biden’s idea, Fauci says. In them, Fauci has (with the help of slides) clarified everything from why people couldn’t assume that if they were vaccinated they were immune from getting infected with the virus to breaking down why two doses of the vaccines are important to what impact variant strains are having on vaccine immunity.

It’s all science, but that doesn’t mean it’s what everyone wants to hear. Fauci remains a target of frustration over what many feel are overly restrictive public-health measures such as social distancing, mask wearing and an unprecedented closure of businesses. And threats against his life and his family, which reached a peak last year, mean a rotating team of security guards continues to shadow him. “Unfortunately, the necessity still remains,” he says. “I still get threats.”

What most draws the ire of detractors is not the evolving nature of scientific knowledge itself, but its consequence: changing advice to the public—which some interpret as uncertainty or even incompetence on the part of the public-health experts who impart it. The COVID-19 pandemic, Fauci says, “confirmed what I learned with other outbreaks, and that is that you really have to be humble and modest enough to know that you’re learning as you go along. What you see in January and February maybe triggers recommendations, guidelines and conclusions that all of a sudden, as you learn more and more, you realize that maybe you weren’t 100% correct. It’s the whole idea of the evolution of understanding.”

He admits that health experts were wrong about two major things: the early assumption that only people with symptoms could spread the disease, and the belief that the virus couldn’t remain in the air long enough to float an appreciable distance. But they were willing to admit those mistakes and amend their advice based on what they learned. “One problem is that the American public thinks science is better than it is,” says Dr. Otis Brawley, former chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society and now professor of oncology and epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University. “They don’t realize it evolves over time. The only thing I wish Dr. Fauci had done—and he did say this, but maybe he didn’t say it loudly enough—was that we are early in this disease. We are going to learn. Some rules are going to change as we learn. If he had warned people of that more loudly, maybe he would have an easier time now.”

As members of Congress accuse him of draconian and inconsistent responses to the pandemic, Fauci says he is not deterred. The “enormity of the problem, and the potential positive impact you can have by staying in the game” gives him the fortitude to weather the constant assaults meant to weaken his resolve, he says. Brawley, who like Fauci was educated in the Jesuit tradition, credits Fauci’s commitment to serving others to the sense of obligation they were taught. “Almost every individual in that position has to make a decision,” says Brawley. “At what point do I announce I can’t deal with this anymore and leave? There is the argument that one should stick with it and take the abuse because you are still having some influence and there may be big, big questions in the future where you really need to be there to make your voice heard. We were taught that sometimes you have to accept the hit to yourself for the greater good.”

For Fauci, learning the necessity of self-sacrifice came during the early days of fighting another worldwide epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s: HIV.

Then as now, he found himself at the bull’s-eye of vitriol and blame, at that time from activists in the AIDS community. He was the symbolic white coat of an indifferent government that wasn’t willing to address an epidemic that largely affected marginalized populations including gay men, IV drug users and sex workers. As director of NIAID, which oversaw testing of new AIDS drugs, Fauci was the natural scapegoat. “There was a very slow-moving research effort with nothing really to help people [with HIV],” says Mark Harrington, co-founder and executive director of Treatment Action Group (TAG), an AIDS advocacy organization, whose members, then known as ACT UP, organized an infamous “Storm the NIH” protest in 1990 during which he and other advocacy leaders were arrested. “Fauci was the one in charge, and nobody else was. There was nobody else we could have gone to.”

The late Larry Kramer, the AIDS advocate notorious for his caustic style, wrote a commentary in 1988 in the San Francisco Examiner calling Fauci an “idiot” and a “murderer” for not being flexible enough to modify the way new drugs were tested so scientists could produce more tangible results sooner. “I thought, Whoa, if you wanted to gain my attention, you definitely gained my attention,” Fauci says of the screed. At the time, only people who participated in clinical trials could benefit from experimental drugs that were still unproven when it came to safety and effectiveness. ACT UP and other activist groups pushed Fauci to consider allowing people not in studies to access experimental drugs, as long as they understood and consented to the risks involved. “Several of the activists were saying, ‘Tony, take a deep breath and just think about it. What the hell is wrong with somebody taking a drug who can’t be on a clinical trial?’ I thought about it, and they were right,” says Fauci. The practice evolved into what is now known as “compassionate use.” Last year, that program gave thousands of severely ill COVID-19 patients access to the antiviral medication remdesivir before it was approved by the FDA in October, and possibly saved lives.

The COVID-19 vaccine trials piggybacked off another HIV-era innovation that Fauci helped to orchestrate: the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), a network of researchers and institutions that conduct studies of promising HIV drugs and is run by NIAID. Under Fauci’s direction, for the first time in NIAID history activists were invited to help design and recruit volunteers for the trials. Because of their connection to the HIV community, these advocates became an invaluable resource for the scientists trying to understand what to prioritize and how to effectively structure studies. The community-based programs established by the ACTG were critical in enrolling people in the COVID-19 vaccine trials from minority communities disproportionately affected by the disease and who would benefit most from an effective vaccine.

Harrington recalls that even in the early days of the HIV epidemic, Fauci “was hearing and learning to understand what we were saying.” It’s a behavior Fauci has nurtured since his childhood in Brooklyn, where his father owned a pharmacy in Dyker Heights. On evenings and weekends, young Fauci would deliver neighbors’ prescriptions on his Schwinn. He rode the subway and bus into Manhattan to attend a Jesuit high school on the Upper East Side, where, he says, “the motto was service to others.”

His studies there pulled him in two very different directions. “I wanted to understand society and history and how civilizations evolved,” he says. “I also became fascinated with science and by the fact that you could discover unknown things. And that you could solve problems in a way that is sound and irrevocable.” That led him to an unusual undergraduate degree at Holy Cross in premed and Greek classics—a nod to his growing interest in both the straightforwardness of science and the humanism of his Jesuit education. After graduating, Fauci went to medical school at Cornell, and as the country became more deeply involved in the Vietnam War, the newly minted M.D. chose to serve in the U.S. Public Health Service, to fulfill his military obligation. He was promptly assigned in the early 1970s to the National Institutes of Health and NIAID, where he would spend the rest of his scientific career.

Fauci quickly became engrossed in the immune system, a bit of a scientific backwater and black box at the time. But there was something about infectious diseases and the way the body fought them that proved irresistible to him. “Infectious diseases had characteristics that fit with my fundamental personality profile—they’re acute, and they either kill you or you get better,” he says. “There is very little intermediate there. You can prevent them and you can treat them, and something about that was, bang, bang, bang, that I really liked.” All the while, Fauci continued to treat patients as a physician-scientist. When he saw the enormous cost the COVID-19 pandemic was having on doctors, nurses and first responders on the front lines, Fauci wasn’t just empathizing from afar. “Being somebody who has been in the trenches in the early years, taking care of very sick HIV-infected individuals, before we even knew what the virus was—I’ve been there,” he says. “So, when I see the health care providers today, doing their work without hesitation, that gives me a good feeling about who we are.”

That sincerity hasn’t been lost on those on the COVID-19 front lines. As he left work late in the evening last Dec. 24—his 80th birthday—more than a dozen members of the Bethesda–Chevy Chase rescue squad and the National Institutes of Health fire department serenaded him with “Happy Birthday.” Fauci jumped in front of them for a socially distanced selfie.

More than a year into the pandemic, Fauci remains energized by the challenge. When he talks about the first COVID-19 vaccine to enter human trials—in large part thanks to his early investment in the project—his passion is undeniable. “[It’s] a great example of how you can go from something that somebody is working on as a basic scientist for five or 10 years, and it ultimately gets to the point where it becomes translatable in a really important situation such as this pandemic,” he says.

Fauci gives much of the credit for the speed at which the first COVID-19 vaccine moved into human testing to Dr. Barney Graham, deputy director of NIAID’s Vaccine Research Center, which was originally created as a joint program between NIAID, the National Cancer Institute and the NIH Office of AIDS Research, but is now under Fauci’s direction at the NIAID. Since 2013, Graham had been working out the genetic formula for generating just the right configuration needed for a potent respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine. He was still at it when the novel coronavirus dubbed SARS-CoV-2 pounced on the world. In December 2019, as more cases of the mysterious pneumonia in Wuhan, China, started to pile up, Fauci recalls, Graham was confident he could apply what he’d learned to create a vaccine against the new coronavirus. “Barney said, ‘Get me the damn sequence, that’s all I need,’” Fauci says. On Jan. 10, that sequence materialized on an open genetic database. “It took Barney about 50 seconds to … pull out the spike protein” and figure out the sequence coding for the correct formation of the protein that would become the target for five of the six COVID-19 vaccines that the U.S. government helped to develop or, in Pfizer-BioNTech’s case, purchased early on. (Today, three of those have received FDA authorization.)

But at that point, it was up to Fauci to decide if the world even needed a COVID-19 vaccine. “We’re talking about January, and nobody is excited about this,” he says. The first U.S. case had not yet been reported, and there was still a naive sense among the Trump Administration that maybe the virus would simply go away after burning out overseas.

Fauci’s experience with HIV, however, had taught him prudence, since that epidemic too began with a handful of cases that ballooned into millions. It was likely, he knew, that the early reports that SARS-CoV-2 couldn’t spread easily from person to person were “nonsense,” he says. He gave Graham the green light, and a million dollars, to start building the vaccine. He reasoned it was worth a try since SARS-CoV-2 was the third coronavirus to plague the world, and previous efforts to develop shots against one of them, MERS, were shut down when cases dwindled. A successful COVID-19 vaccine wouldn’t just pay off now; it could be useful as a foundation for fighting any other coronavirus that might emerge down the road. Plus, this time, Fauci was excited about a new technology that relied on the genetic material called mRNA, which was being used by one of NIAID’s partners, Moderna, a biotech company in Massachusetts.

The mRNA technology shaved months off the typical vaccine-development timeline. About three months after the genetic sequence of SARS-CoV-2 was published, Pfizer and BioNTech scientists submitted a request to the FDA for emergency-use authorization of their mRNA-based vaccine, after studies showed it was 95% efficacious in protecting people from COVID-19 disease.

Fauci received the news directly from Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla on Nov. 8 as he was enjoying a Sunday beer and a socially distant chat with a neighbor in the backyard. “He said, ‘Tony, are you sitting down? You are not going to believe the results; they’re unbelievable,’” says Fauci, who also wasn’t expecting nearly such a success. A week later, Moderna reported similar results, and the two vaccines became the first to receive emergency-use authorization in the U.S. They remain the bedrock of the country’s vaccination program. “This [mRNA] technology will revolutionize vaccinology,” says Fauci. “The HIV people are really interested in it now.”

In many ways, Fauci’s 2021 is radically different from his 2020. In others it’s exactly the same. Aside from the three weekly press briefings he attends, Fauci also fields four or five calls a day from Jeff Zients, who conveys questions from the President or seeks advice on policies the Administration is considering. Looking toward the next year, Fauci says we shouldn’t be so focused on the specific number of people who need to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity. Instead, he says, we should keep concentrating on vaccinating as many people as quickly as possible. On that front, after a surge of people rolling up their sleeves over the winter and early spring, the U.S. may now be hitting a wall of vaccine hesitancy. “It’s a difficult question, and I don’t think there is an easy answer,” he says about ways to reach people who aren’t eager to get vaccinated. “We just have to keep trying to get the message out based on the evidence and the data. We can’t give up.”

Fauci won’t feel comfortable saying we’re near the beginning of the end of the pandemic until new infections start to come down “somewhere south of 10,000 a day” from the current 33,000 infections a day on average. But unlike last year, he now sees a path toward that goal because of vaccinations.

He hasn’t forgotten the terrible toll that COVID-19 has taken on American families, often reminding people that as rosy as things may look now with the vaccines that are available, COVID-19 has claimed more than 585,000 lives in the U.S. alone. The worsening situation in India is another stark reminder of the danger of becoming complacent.

When I ask whether he thinks we’ll be able to put COVID-19 behind us, or whether it will look more like a flu that comes back in slightly different forms each year, he responds with typical frankness. “I’d love to give you a confident answer to that. But I have to be totally honest—I don’t know,” he says. “Even if we get the infection rate very, very low in our country, with the overwhelming majority of people vaccinated, there will always be the threat of new variants coming in because there will be active virus in other parts of the world. I think at least in the next couple years we are going to have to be really careful about the virus returning.”

That could mean annual booster shots of the vaccine, which both Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna are already studying. It also means Fauci will continue to be busy. He’s still not getting much sleep these days, but he still doesn’t mind. “The aggravation and stress of being at odds with the [Trump] Administration—that’s stressful.” Under Biden, he says, “I’m putting in more hours and working harder, quite frankly, but it’s in the realm of not being attacked and in the realm of being supported, which makes a big difference.”

His role as the country’s chief medical adviser will ensure that his legacy will be felt long after this pandemic fades away. The communication skills that have made him an effective translator of science for the lay public is already lighting sparks of inspiration in the next generation of potential physicians and scientists. In the past year, applications to medical schools have jumped, in some cases by as much as 18% over the previous year—no doubt in part because lockdowns are finally giving people the time to consider and complete the involved applications, and in part because of the selfless example of frontline medicine throughout the pandemic. But also, as admissions officers are learning from students who cite Fauci as a role model, because of the so-called Fauci effect.

That comes as no surprise to Dr. Luke Messac, an emergency-medicine resident at Brown University who cares for COVID-19 patients. When he was a junior at Harvard, Messac emailed Fauci on the off chance the NIAID director would answer a few questions about his role in orchestrating the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, one of the most robust and productive HIV-treatment programs in the world. Not only did Fauci respond, but he invited Messac to his office in Bethesda, where they spent over an hour discussing the topic. When Messac sent Fauci the finished paper, Fauci responded with a glowing review and asked if he could cite some of the conclusions in his future talks. In July 2020, Messac shared his experience, and Fauci’s response, on Twitter and was overwhelmed by the positive reaction. “I thought it might help people to better understand who he was behind the spotlight when people weren’t looking,” Messac says.

For Fauci, the idea that a new generation of young people may benefit from careers in science or public health as much as he did is the silver lining of the past year, worth the personal insults and the loss of privacy.

“If I’m doing anything to get young people to seriously consider the field of medicine, then I feel really good about that,” he says. “The idea that some young man or woman may decide to go into medicine because they see what I’m doing, that pleases me as much as anything else.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com