On May 25, a bystander outside a Minneapolis grocery store filmed a scene both shocking and unnervingly familiar. “I can’t breathe,” George Floyd gasps, again and again as a white officer, Derek Chauvin, presses his knee into the black man’s neck. And keeps it there.

“I can’t breathe” had become a protest chant almost six years ago, after Eric Garner was slowly killed by a white New York City police officer detaining him for selling cigarettes one at a time on a Staten Island street. His death, also captured by a bystander, stoked the outrage that had erupted in Ferguson, Mo., after the death of Michael Brown at the hands of police, then across the nation in the summer of 2014, as the ubiquity of cellphone cameras placed before the general public a reality always known to minorities.

Black Lives Matter — the movement that, like the videos, made profound use of social media — placed police violence at the top of the United States’ domestic agenda. The movement raised awareness, encouraged reform, and drew a bright line between what could have been dismissed as accusation, and what was plainly true.

The Floyd video, which began circulating online a day after his death, somehow made that line even brighter, more than three years after the succession of America’s first African-American president by one supported by white supremacists. Chauvin was charged with murder on May 29, four days after Floyd’s death, but only after protesters took to the streets not only in Minneapolis but across the country.

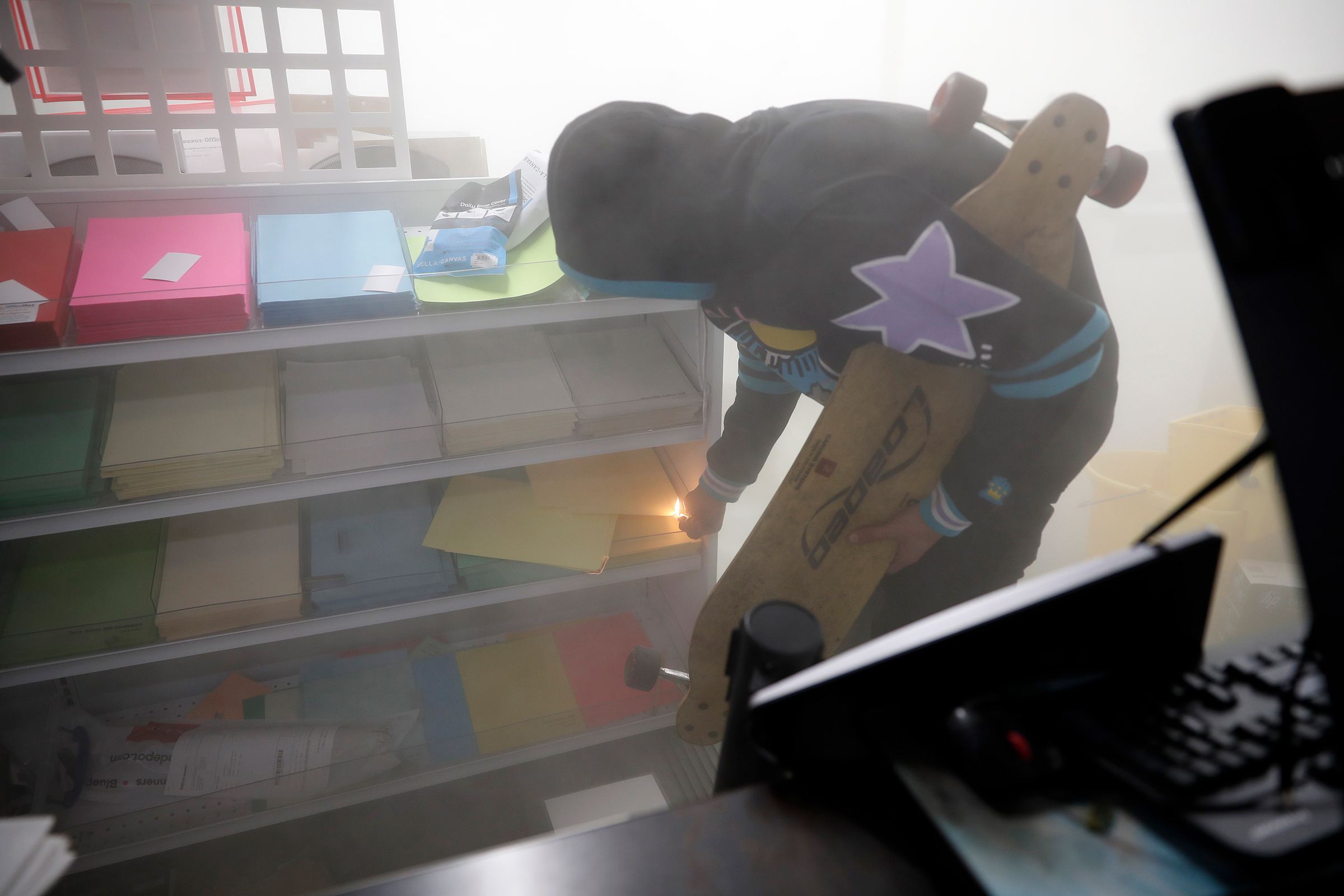

In the City of Lakes, police in riot gear faced off with protesters who greeted tear gas and rubber bullets with their arms raised. On May 28, the 3rd police precinct, where Chauvin and the three officers involved in the altercation were based, was evacuated, then set ablaze.

Much of it was streamed live on video, broadcast live, and captured on cell phones. But there’s a reason that so often what lives in memory are the single images captured by photographers.

“My job is just to document a visual diary and start a conversation,” says Star Tribune photographer Richard Tsong-Taatarii. “Obviously, we are in need of a deep conversation about police reform because this keeps happening again and again.”

—With Kathy Ehrich Dowd and reporting by Paul Moakley

“What this woman expressed is what the majority of the people in this country feel about what happened in this video,” says photographer Richard Tsong-Taatarii, of the bystander’s video footage showing a white police officer kneeling on Floyd’s neck. “If you’re any kind of decent human being you obviously have a heart-wrenching gut check when you see this video.”

Tsong-Taatarii has been a photographer with the Star Tribune for nearly 21 years. “When I took the picture,” he continues, “I saw the strong sentiment she was expressing in a way that is protected by our country and the constitution. She did it in a way that we can all relate to.”

Was there anything else he wanted to add? “Support local journalism.”

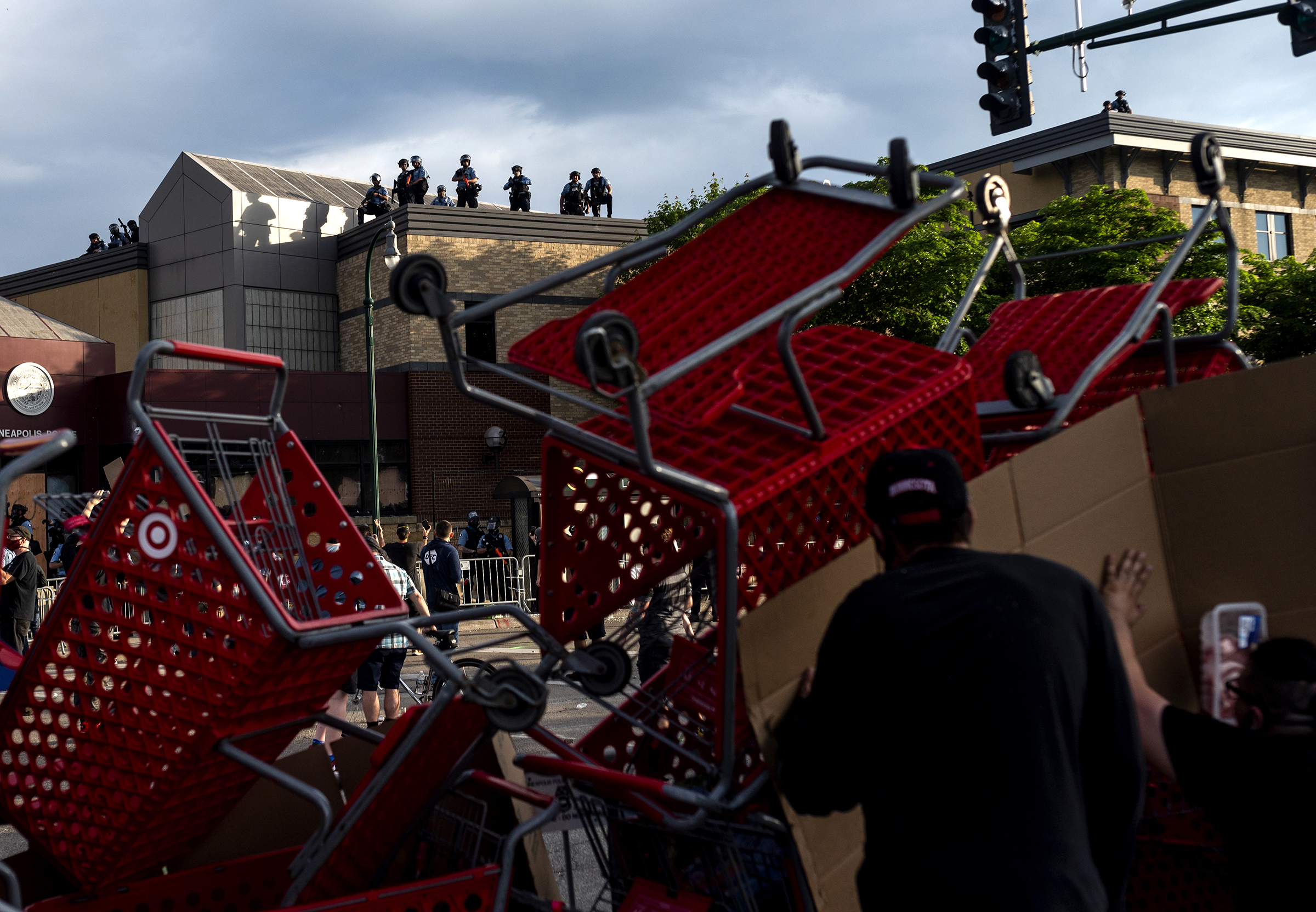

“The moment I saw the video of George being killed I had a panic attack from seeing Derek’s face. How he reacted was pure evil. You can see how he was reveling in the power from pinning this man on the ground. It was frightening,” said Alexander Vega, 28, a protester (at far-right) in front of the barricade. At the scene, Vega, who said he has protested for years in the Black Lives Matter and Standing Rock movements, said he saw the woman and her son had been tear gassed and jumped in to make sure they were OK, to be calm and breathe deeply.

“This is my city where I have family. Something had to be done,” he adds. “An innocent black man was killed in the streets. I knew right away what my part was in the sense of helping. This is my calling. This is what I’ve done for years — standing in solidarity.”

When asked about the importance of documenting this moment he says, “What’s important is that the media is not showing footage of what the police are doing. In my live streams on Facebook, I describe it … People say, we’re the ruckus. We’re the thugs. That’s how people view us and its not the case. The police are the ones who are the weaponized thugs.”

Kerem Yücel had moved from Turkey in search of “a more peaceful life.” Almost three years later, he and his wife wonder, “Is it safe for my kids or not?”

Yücel, a photographer who works with AFP, compared what he’s seen this week in Minneapolis with the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul back in 2013, where there were peaceful protesters and more violent factions. “I was just expecting that Americans were showing their respect for George Floyd after he died,” he said about the initial protests after Floyd’s death. Since then, he’s felt, “other groups are just waiting for the darkness.”

“I’ve been holed up in my house for two months and this is one of the first things I worked on,” says Stephen Maturen, a photographer who works with Getty in Minneapolis. “It’s a bizarre feeling covering this thing, getting all these pictures and I have this feeling in the background that the video of George Floyd being killed is the most powerful document that there is. The most important imagery has already taken place.”

He adds, “In the middle of a chaotic moment, seeing that picture is a totally grounding thing. It’s like — don’t forget why everyone is here.”

“We look for ways to tell people the story,” says Aaron Lavinsky, a photographer with the Star Tribune for almost six years. Lavinsky has covered a number of similar protests in recent years. When he arrived outside Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman’s house on May 27, he saw a woman and two children holding signs and asked to photograph them.

With their mother’s permission, Lavinsky spoke with Deshawn, during which the teenager admitted sticking to public places when he goes out with friends because he’s worried about negative interactions with police officers. “I’m 15. People younger than me get killed by police,” he told Lavinsky. “I don’t know if I’m next or not.”

Reflecting on this photograph, Lavinsky wondered, “How are they processing this? It has to be tough for these kids. There’s so much pain in this city.”

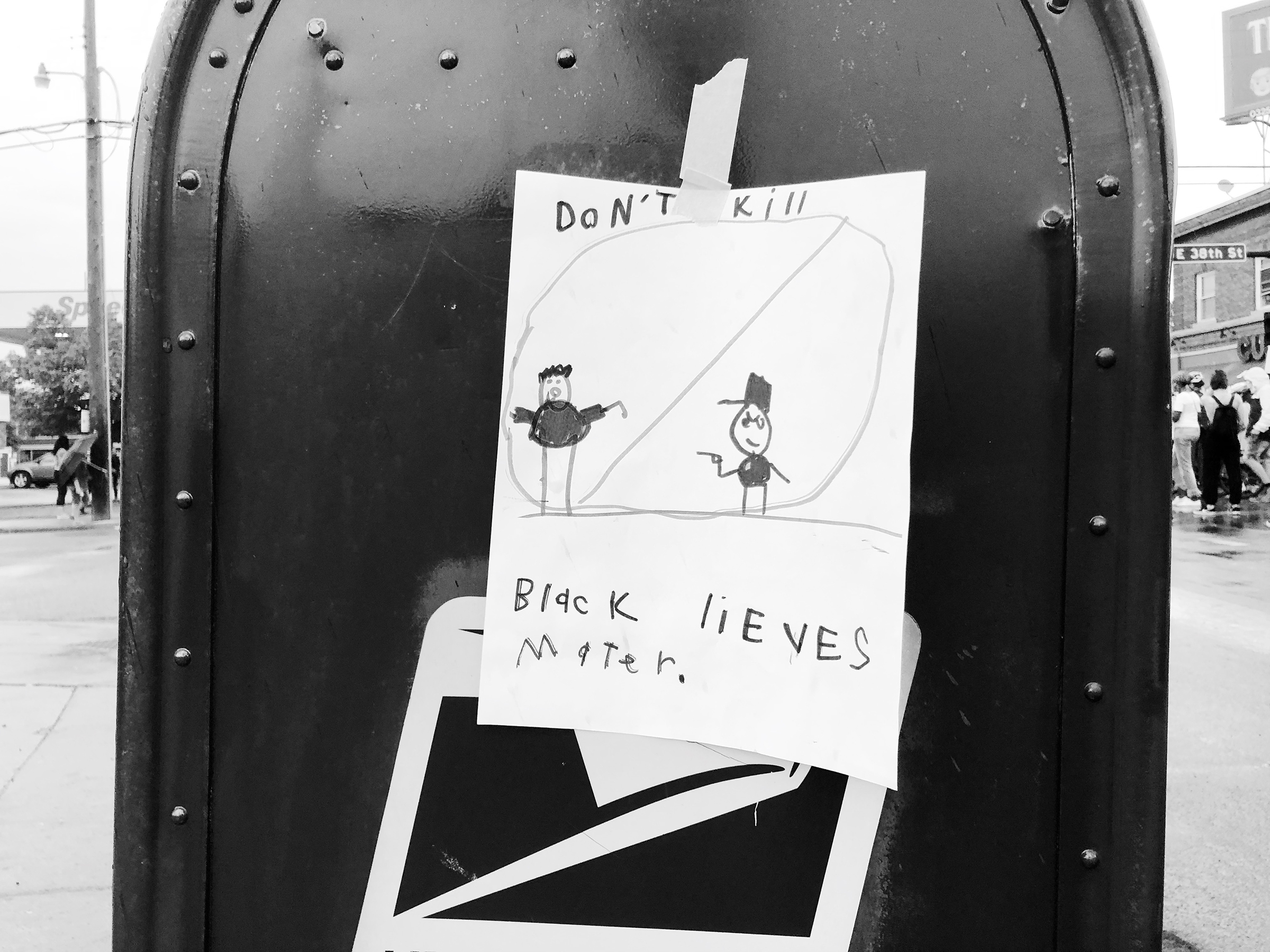

“This photo of the poster made by a child really gets me,” says Patience Zalanga, a Minneapolis-based photographer. “It’s because of the misspelling and the image that they drew. There’s an innocence to it and the heartbreaking reality of the child’s understanding of what happened.”

On May 30, photographer Malike Sidibe said he “couldn’t just sit and watch” anymore and instead brought his camera to a demonstration outside Brooklyn’s Barclays Center. He wanted to “fight for all the black people who have lost their lives to police brutality,” he later wrote. “As a 23-year-old black kid living in New York City, since middle school I’ve always feared for my life. I’ve had a lot of uncomfortable experiences. It’s time for a change.”

“I had never noticed the flag inside the Trump Tower all the times I passed it before,” says photographer Mark Clennon, “but in that moment, I was an active participant in that protest. I’m chanting, too, and my fist is up. The American flag behind the glass, in that gold, gilded case, it’s inaccessible to me. I have an urge to just break through that glass because that flag is for me, too. That’s the visceral feeling I had when I noticed the flag, and I think that’s the feeling this man had when he saw it, too.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com