There was a time in the U.S. when employers could pay workers as little as they wanted, kids toiled in sweatshops, and bosses could lock in employees to prevent them from taking breaks. Frances Perkins halted these practices, defending workers whose lives had become dangerous during the nation’s rapid industrialization.

Perkins was having tea one afternoon in New York in 1911 when she witnessed the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, where 146 workers died after being trapped in the burning building. Horrified, she pushed New York to pass early worker health and safety laws, first as an advocate and later as the state’s industrial commissioner.

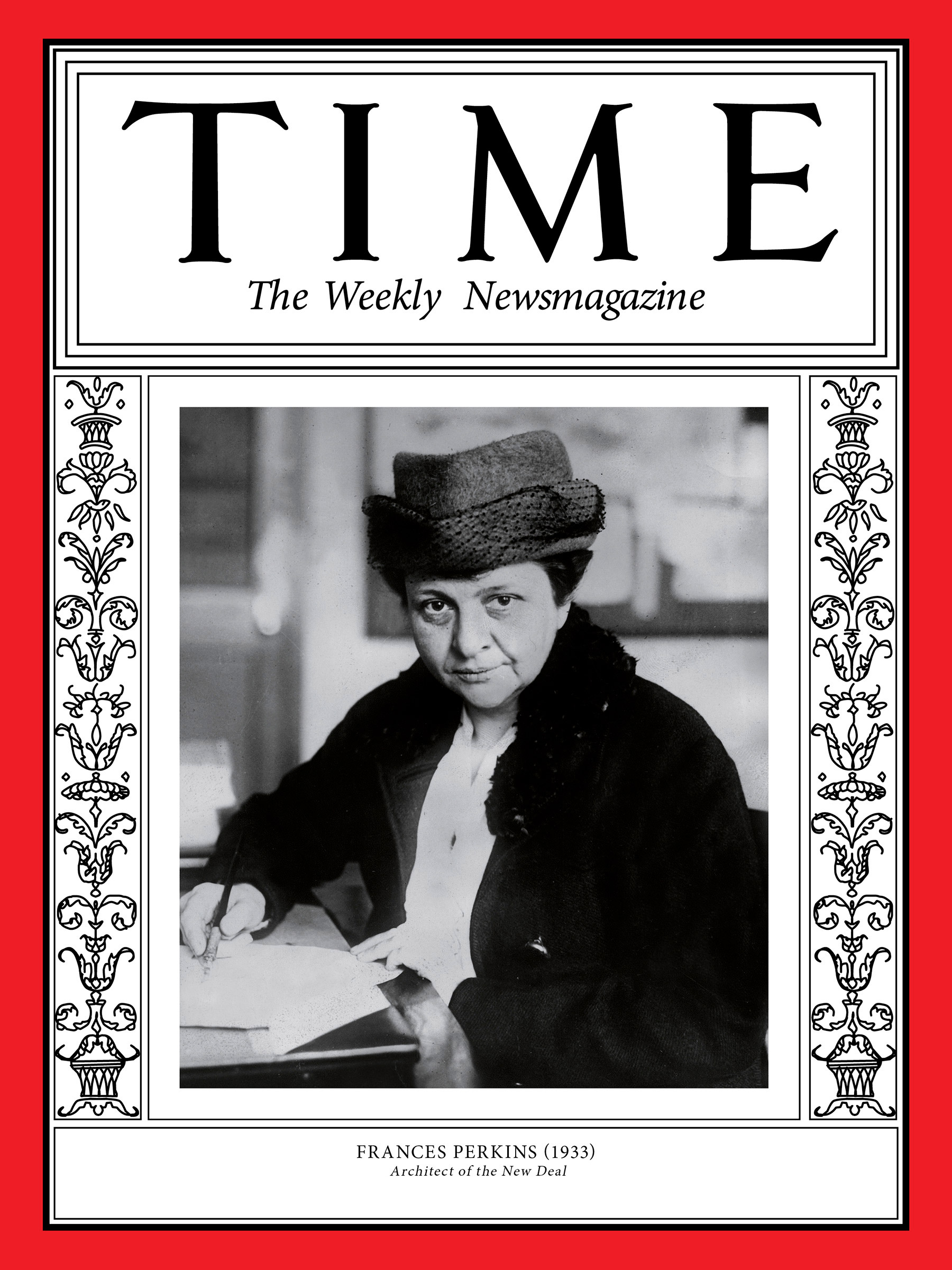

Her work made Perkins such a prominent voice for the working class that Franklin D. Roosevelt asked her in 1933 to serve as his Secretary of Labor. She accepted on the condition that he’d support her in establishing a safety net for workers. “Nothing like this has ever been done in the United States before,” she told him, according to Kirstin Downey, author of a Perkins biography. “You know that, don’t you?”

Perkins was the driving force behind the New Deal, the package of laws that protected average Americans during the Great Depression, and she implemented relief programs that paid unemployed men to work on public projects. She secured unemployment insurance and pensions for the elderly and financial assistance for the infirm in the Social Security Act of 1935; and established a minimum wage, maximum work hours and the eradication of child labor in the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

Perkins served as Labor Secretary until Roosevelt’s death in 1945. “I came to Washington,” she once said, “to work for God; FDR; and the millions of forgotten, plain common workingmen.” —Alana Semuels

This article is part of 100 Women of the Year, TIME’s list of the most influential women of the past century. Read more about the project, explore the 100 covers and sign up for our Inside TIME newsletter for more.