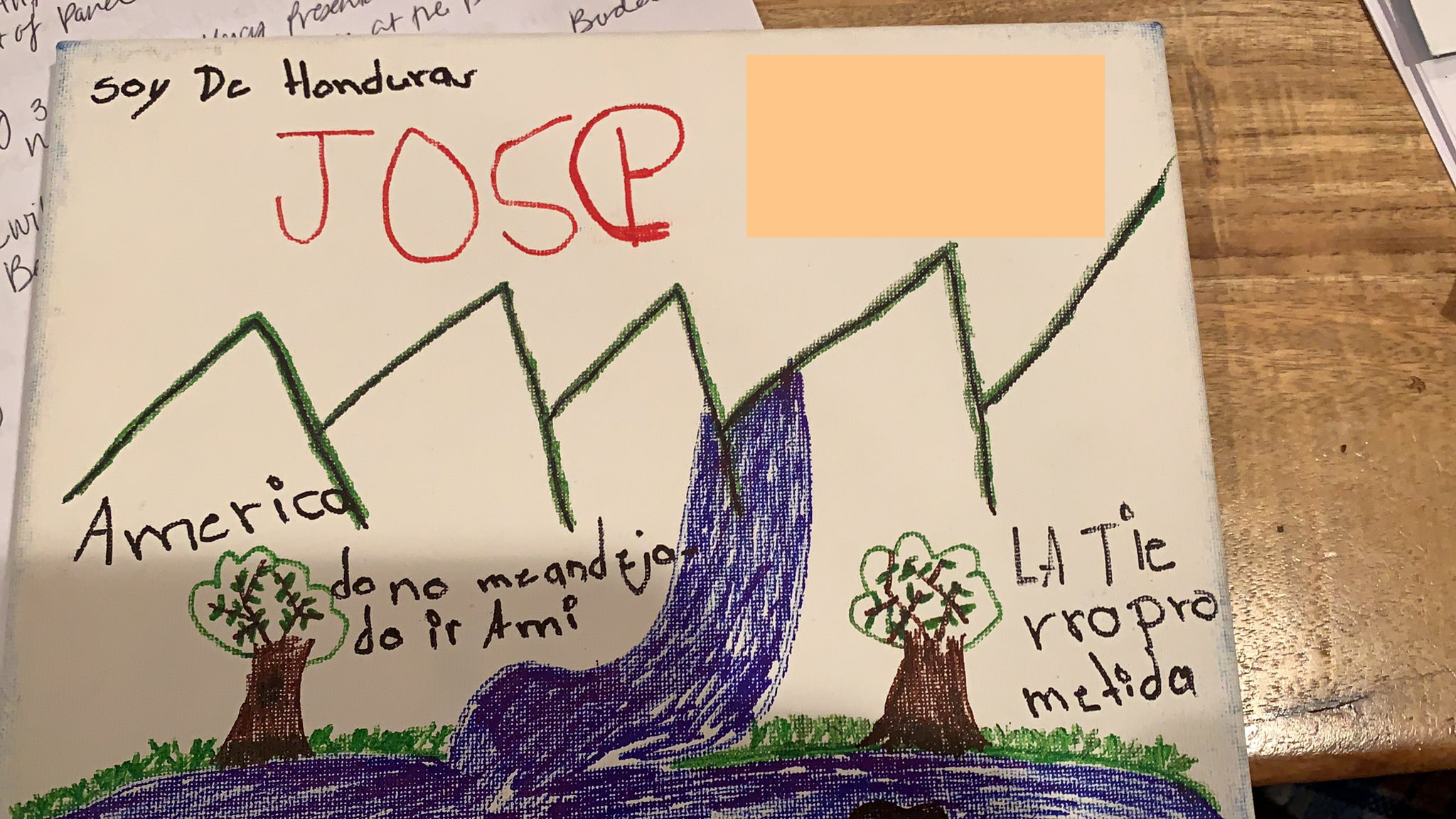

“America, where they didn’t let me in,” writes 11-year-old Jose from Honduras in Spanish next to a picture of mountains and trees on a canvas in blue, green and brown colors. He also drew a river — the Rio Grande that separates him from Brownsville, Texas, where his family hopes to claim asylum. “La tierra prometida,” he writes. “The promised land.”

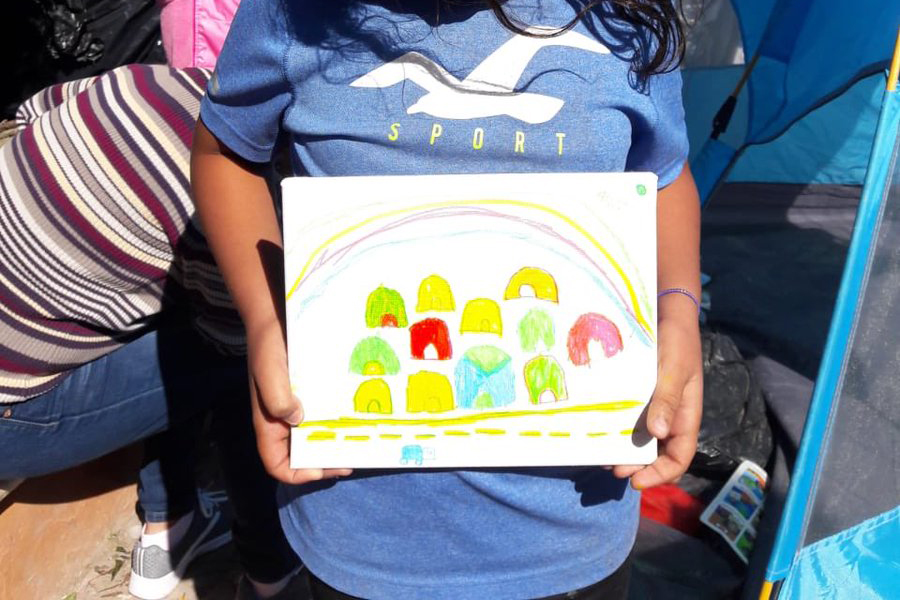

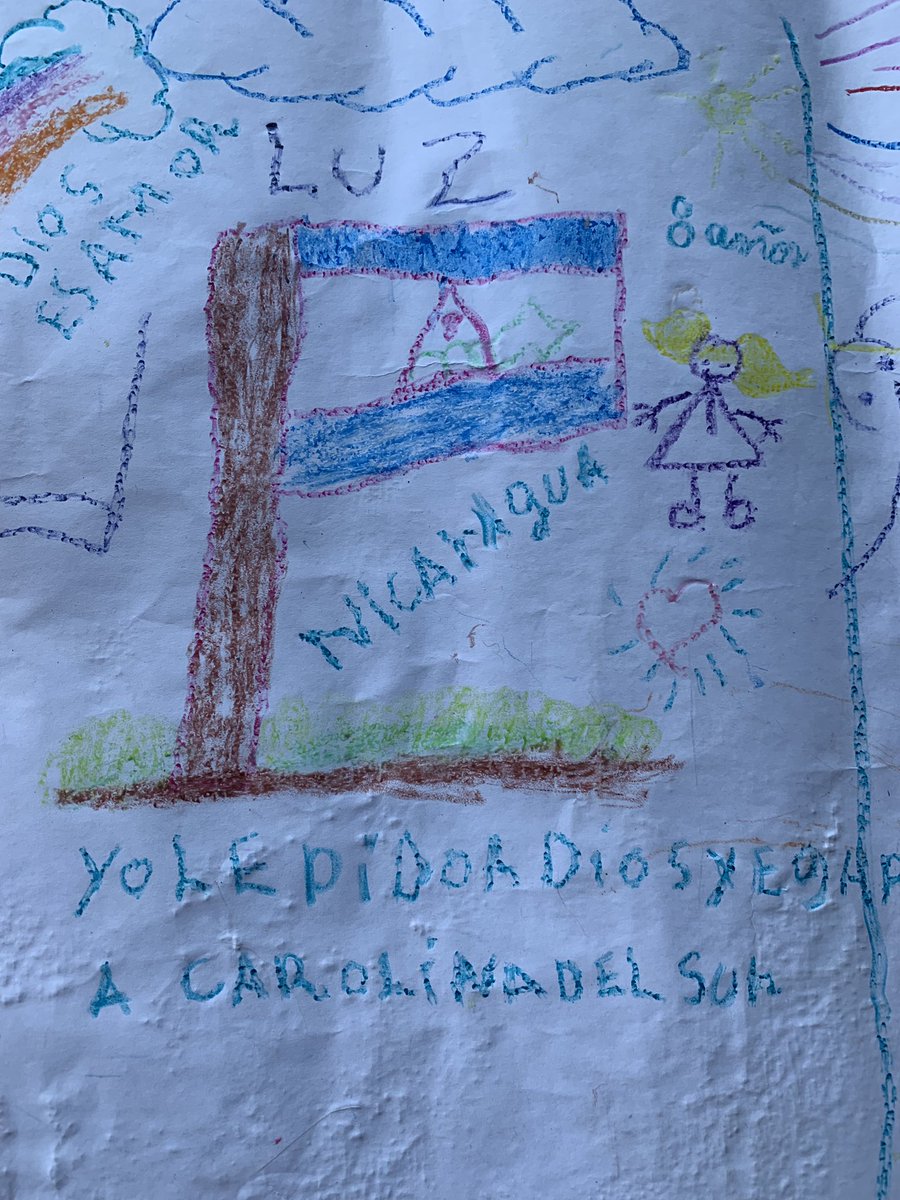

Jose is one of at least 1,450 migrants who are living in a tent encampment on the streets of Matamoros, a city in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas, as a result of the Trump Administration’s “Remain in Mexico” policy. Dozens of children in Matamoros drew their experiences as part of an art project, photos of which were provided exclusively to TIME by Dr. Belinda Arriaga, an associate professor at the University of San Francisco who specializes in child trauma and Latino mental health. She traveled to Matamoros Oct. 19-25 as part of a group of volunteers who provided aid and psychological care to migrant children and their families.

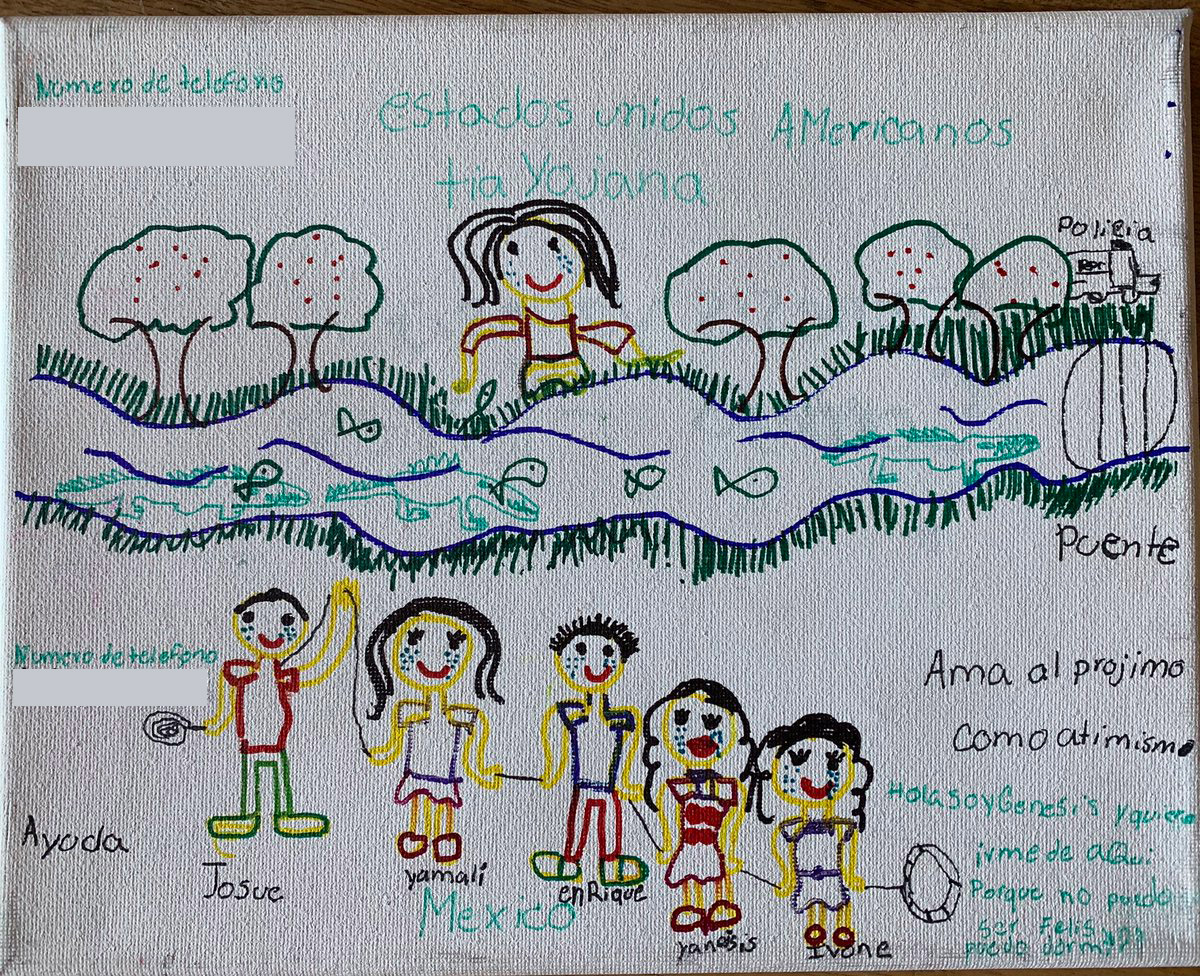

The six drawings depict family members separated by the Rio Grande, children inside cages and images of America. In one photo, a drawing by 9-year-old Genesis depicts crocodiles in a river near a vehicle she labelled “Policía.” Her family, in tears, are standing in Mexico, while her tía, or aunt, cries for them in the U.S. “Quiero irme de aquí porque no puedo ser felíz y no puedo dormir,” she has written on the drawing. “I want to leave from here because I can’t be happy and I can’t sleep.”

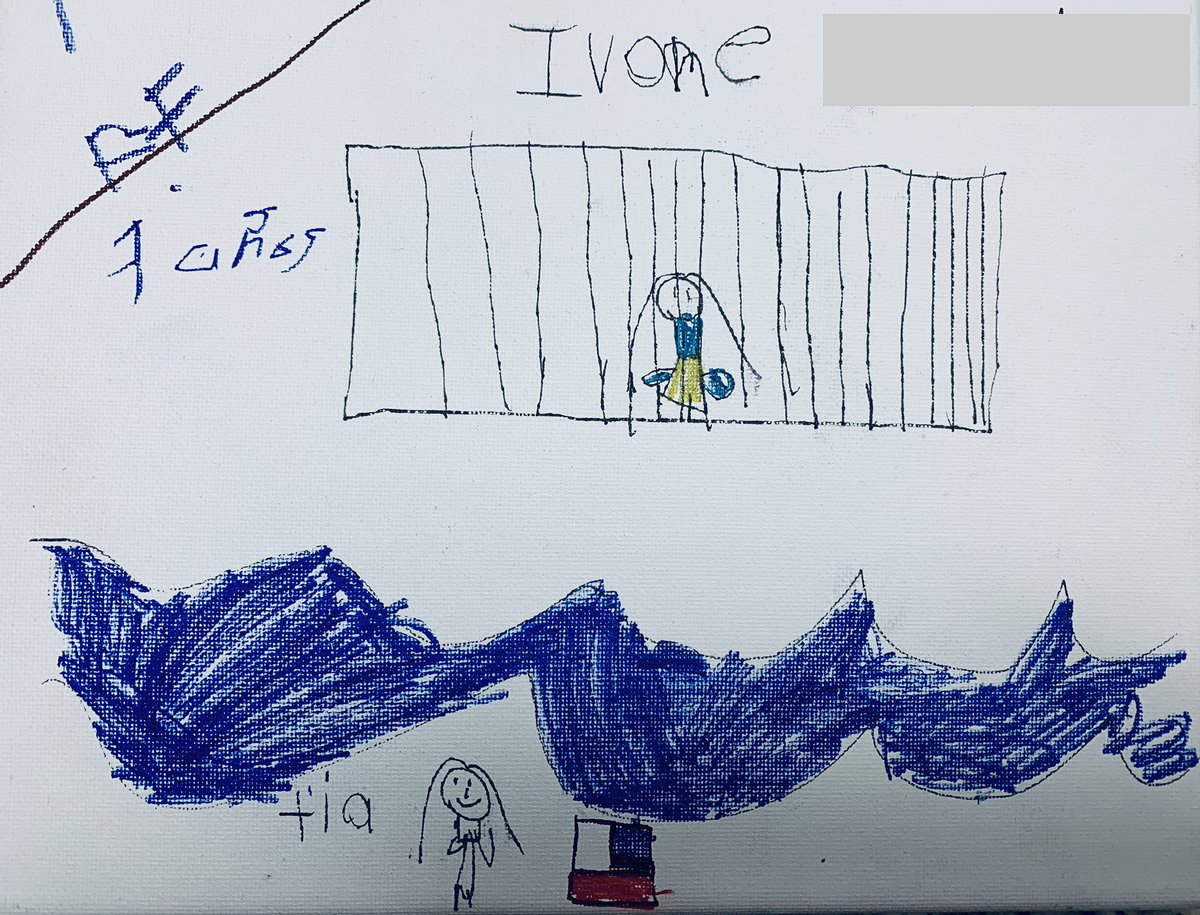

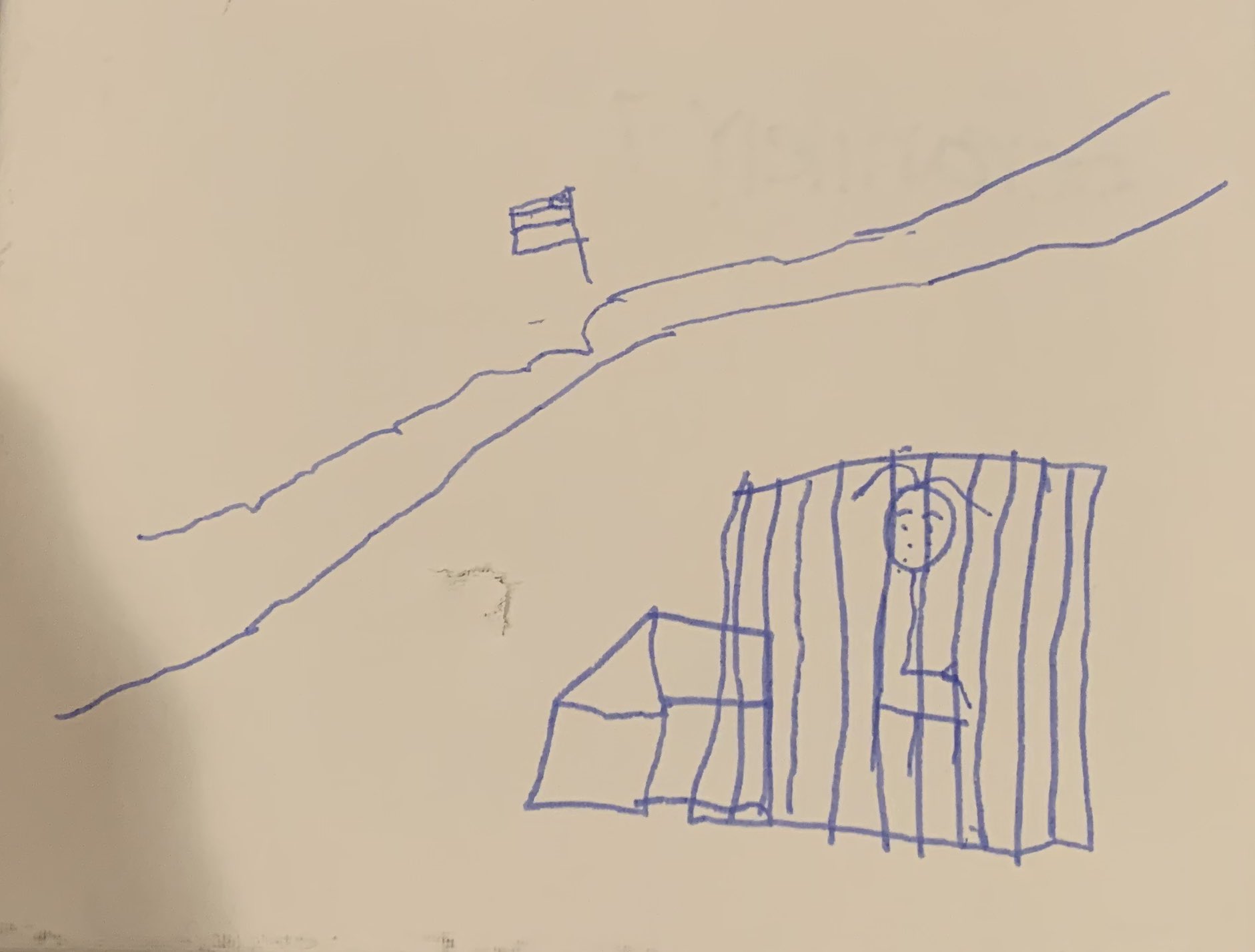

In order to protect the identity of the children, TIME has covered some identifying information in the drawings.

“Their drawings become their voice,” Arriaga adds. “When they started handing me one-by-one their pieces, it was really jolting to see what they were drawing… the drawings help us understand the trauma that this country is inflicting on them.”

Arriaga has traveled from San Francisco to Brownsville and McAllen, Texas, six times to work with children released from family detention since the height of family separation under the Administration’s Zero-Tolerance policy. Arriaga provided similar drawings to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) this summer made by children who depicted themselves in cages after being released from a Customs and Border Protection family detention center in the McAllen region.

This month, on her seventh trip to the Rio Grande Valley region, Arriaga was one of 24 members of the Bay Area Border Relief (BABR) organization who traveled to Matamoros. Many volunteers provided donations, food and therapy to more than a thousand people sleeping in tents or outside at a plaza near the port of entry. Arriaga worked with children who have been waiting in Mexico under the Department of Homeland Security’s Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) — also known as “Remain in Mexico” — which requires asylum-seekers to wait in Mexico while their legal case for asylum progresses. Arriaga participated in group sessions with the children, including sessions that allowed children to draw and express what they’re feeling and what message they wanted to share with the world. About 40 children and some parents participated, Arriaga says.

Dr. David Martinez, a clinical psychologist and assistant professor at the University of San Francisco, was also on the trip and provided one-on-one therapy to children there, an effort he called “psychological first-aid.” The children were clearly traumatized, he says, and his own experience and studies have shown him that it’ll take years before the effects of the trauma becomes obvious.

“I do see a lot of resilience, but there’s only so far that can go if things don’t change,” he says. “What happens in adolescence, especially early on in childhood, kind of defines your life. Being exposed to stress, trauma, adversity… it can lead to a lot of poor mental health outcomes or physical health outcomes.”

Arriaga says her encounter with the children in McAllen over the summer was ultimately hopeful. “There was fatigue and exhaustion, yes, but there was hope,” she says. “But with these children [in Matamoros], what we walked away with was a complete sense of desperation… they’re screaming for help.”

Seven-year-old Ivone drew a picture of herself inside of a cage near the river. Her tía waits for her on the other side, standing next to an American flag. An unidentified 7-year-old drew a similar picture. “It’s an emotional trauma that is not easily going to be erased,” Arriaga says. “What they’re living with and what they’re enduring is something that is going to emotionally impact them for a long time.”

Many of the children are from Central America. TIME for Kids recently traveled to Honduras to interview children and families about their lives there. Many children who remain in Honduras have a family member who has migrated to the U.S. or know other children who have made the journey.

Young asylum-seekers in Matamoros like Jose, Genesis and Ivone sleep in tents that have been donated to them, and rely on food that volunteers from both sides of the border attempt to bring them on a daily basis, according to seven volunteers who have been on the ground who spoke to TIME. These volunteers say asylum-seekers go to the restroom in portable bathrooms volunteers have rented using donated money while sanitary napkins, clothes, diapers, other supplies and medical care are also provided by donation. Shower tents were recently built where the migrants use a bucket of water and a cup to bathe. Many also jump in the Rio Grande to wash themselves and their clothes. A team with Doctors Without Borders (MSF) in Matamoros has also documented cases of diarrhea, hypertension, diabetes, psychiatric conditions and asthma amongst the asylum-seekers. MSF has conducted at least 178 medical consultations over the course of three weeks this month, 58% of which were with children under 15 years old, according to the organization.

A spokesperson for the city of Matamoros did not immediately return a request for comment. Earlier in October, government official Enrique Maciel, a representative for the Matamoros Delegation of the Tamaulipas Institute for Migrants, a state-run agency, told reporters that the asylum-seekers are not the responsibility of the Mexican government, but that the city is committed to providing shelter for public health and safety purposes.

At night, with no way to lock their tents, migrants are susceptible to robbery and other crimes against them, including rape and kidnapping. The U.S. government has issued a travel advisory for the state of Tamaulipas, urging Americans not to go there. There’s no law enforcement oversight, save for the military and Customs officials who guard the port of entry nearby. Volunteer lawyers from all parts of the country also frequent the area, looking for opportunities to represent families they believe should be excluded from MPP and helping them fill out asylum documents that the U.S. government provides in English.

“These people are prey to anybody who wants to come and take advantage of them,” says Lilli Rey, the founder of BABR. She and her daughter were also a part of the recent trip to Matamoros. “For the United States to treat these human beings like this — we should all be ashamed.”

Matamoros doesn’t have the infrastructure to house so many people in shelters, says Erin Thorn Vela, an attorney with the Texas Civil Rights Project based in McAllen. “At the beginning what it looked like was an attorney going out on Saturday night and saying ‘look, gather around me, I can tell you how to fill out an asylum application,'” she tells TIME.

The city of Matamoros has also attempted to create a shelter, the opening of which was cancelled. The cancellation followed criticism its location far from a port of entry would expose asylum seekers to exploitation and violence, according to Andrea Rudnik, a cofounder of Team Brownsville, an organization that has provided daily meals and other resources to migrants in Matamoros since July 2018. A local recreational center is being converted into a facility that could shelter up to 300 of those waiting for their asylum cases to be processed.

Customs and Border Protection tells TIME it has enrolled more than 55,000 people in MPP. Many stay near U.S. ports of entry throughout the border as a result of MPP, which was implemented in January 2019. The policy didn’t begin in Matamoros until July of this year, leading to nearly 1,450 people sleeping on the streets in that same month, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), a research organization based out of Syracuse University. Many of the volunteers say the number has grown significantly since July.

Many have been living at the encampment — which grew organically — since before the implementation of MPP as a result of the Administration’s metering policy, which required them to wait in Mexico and make an appointment with U.S. officials before being allowed to make an initial claim for asylum. Some migrants have drowned in the Rio Grande trying to cross the border after being told they would have to wait for months in Mexico. Organized crime in Matamoros further endangers the asylum-seekers, who the volunteers say are targeted for ransom, or offered jobs like prostitution by local gangs.

“Mexico is providing humanitarian protections and even work-authorizations to these individuals during their stay,” DHS spokesperson Matthew Dyman tells TIME in a statement. “Mexico has stated it would authorize the entrance of those returned under MPP for humanitarian reasons, in compliance with its international obligations, while they await the adjudication of their asylum claims in the United States. Mexico has said it will provide aliens with legal status to work, offer jobs, healthcare and education to such individuals according to its principles.”

The agency called MPP an answer to the “security and humanitarian crisis on the southern border,” when the policy was announced in January. Since thousands of Central American migrant families have arrived at the border to claim asylum, U.S. immigration courts have faced a backlog in processing the cases.

The Administration’s MPP policy has faced legal challenges, the most recent of which is awaiting a decision from the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

The slow appeals process has led volunteers on the ground to work faster and harder, says Vela, the TCRP attorney. “That encampment has been growing since August,” Vela says. It’s easily three times as large as it was before MPP, and the amount of resources has not gotten a whole lot bigger.”

BABR traveled to Brownsville this month with a U-Haul and another truck-full of donations, including clothes, diapers and Beanie Babies and teddy bears for the children. They were not permitted to drive the rented vehicles across the border, so some members of the group found a parking lot near the port of entry on the U.S. side of the border, and began unloading the supplies onto small wagons that they walked across the border one-by-one until everything was dispersed at the encampment. Meanwhile another group of the volunteers began prepping dinner for more than 1,000 people, while Arriaga and Martinez did their work with the families.

It was heartbreaking, Arriaga says, to receive the drawings from the children.

“I try to instill how special they are, and that they’re beautiful and that they’re loved,” she says. “I told each and every one of them, there are so many in the United States that care about you.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Jasmine Aguilera at jasmine.aguilera@time.com