The episode that now has President Donald Trump staring down a House impeachment inquiry began, as many important moments in American history have, with a whistle-blower.

A U.S. intelligence official has accused Trump of urging Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to seek out evidence of wrongdoing on the part of former Vice President Joe Biden, the frontrunner to face Trump in the 2020 presidential election. The claim relates to calls that took place in July and August, and the Inspector General of the Intelligence Community Michael Atkinson alerted House Intelligence Committee chair Adam Schiff about the complaint on Sept. 9.

Trump has called the conversation he had with Zelensky a “very friendly and totally appropriate call,” but as Director of National Intelligence Joseph Maguire testifies before the House Intelligence Committee on Thursday, the whistle-blower’s complaint has been made public — and it will be up to lawmakers to decide if they agree.

While the whistle-blower’s identity is still not publicly known, he or she has been praised in the court of public opinion. Former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe hailed the decision to bring the complaint as an act of “incredible courage.”

America’s history with whistle-blowers is as old as the country itself, but the popular idea that they are courageous hasn’t meant whistle-blowing isn’t still risky, says Tom Mueller, author of Crisis of Conscience: Whistleblowing in an Age of Fraud, out Oct. 1. And in the intelligence community, where sharing secrets is a loaded idea, whistle-blowing is even more complicated.

The origins of the term “whistle-blower” are murky — one theory holds that it’s a reference to the whistle blown by British policemen when they saw foul play, and another says it’s a sports reference to the whistles blown by referees — but the principle dates back to medieval England by way of Roman law. Central to the existence of whistle-blowers is the concept that sometimes individuals, not governments or law-enforcement, need to be the ones who raise the alarm about wrongdoing.

At a time when there was no national police force, people who noticed transgressions could report them to the King’s representatives, under what was known as the qui tam provision. (That name comes from the phrase Qui tam pro domino rege quam pro se ipso in hac parte sequitur, meaning “He who sues on behalf of our Lord the King and on his own behalf.”) To incentivize this kind of whistle-blowing, and in recognition of the negative social consequences that might come with it, the government made it a lucrative proposition: if a conviction followed, the person who did the reporting got some of the bounty. The earliest known example of the application of qui tam is King Wihtred of Kent’s 695 declaration: “If a freeman works during the forbidden time [i.e., the Sabbath], he shall forfeit his healsfang [i.e., pay a fine in lieu of imprisonment], and the man who informs against him shall have half the fine, and [the profits arising from] the labor.”

These English provisions about whistle-blowing carried over to the British colonies in North America. The federal government, even in its early stages, recognized whistle-blowing and the need to alert Congress as soon as possible about wrongdoings by people working with or for the government. On March 25, 1777, Marine captain John Grannis told the Continental Congress that he and nine other sailors saw the commander-in-chief of the continental navy, Esek Hopkins, treating British prisoners inhumanely aboard the USS Warren, and that the commander would refer to Congress as “a pack of damned fools.” On July 30, 1778, legislation was passed declaring that anyone who served the U.S. had the duty to tell Congress as soon as possible about any “misconduct, frauds or misdemeanors” committed by others in government service.

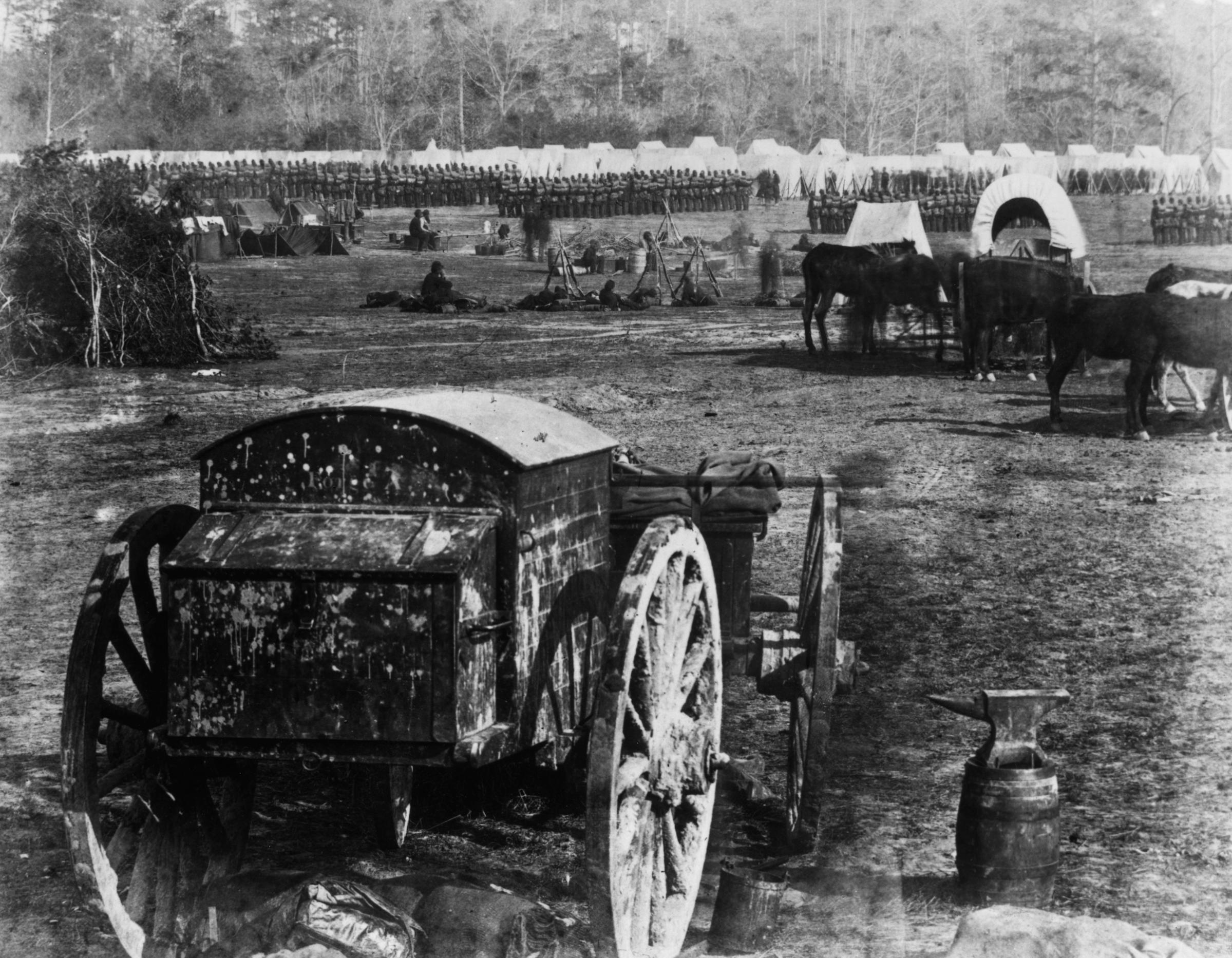

But the major case that shaped American whistle-blower law came during the Civil War. The rush to outfit the troops for war led to shortages of horses, wool and gunpowder — and a rush for companies to make money by selling shoddy goods to the needy Union Army. New York Congressman and abolitionist Charles H. Van Wyck questioned hundreds of witnesses to such fraud, putting together a report that led to the 1863 passage of the False Claims Act. The law established fines for contractors who cheated that system, and said that a whistle-blower who started a False Claims suit — the person this law termed “a relator” — would get 50% of the money if the case was successful.

“It has this qui tam provision that allows an individual, a private citizen, to become a private attorney general and actually prosecute the case on behalf of the ordinary people,” says Mueller.

The law was nicknamed “Lincoln’s Law” after President Abraham Lincoln said he hoped it would empower a different kind of army of “citizen soldiers,” or whistle-blowers, to keep a watchful eye. This law is still on the books.

Defense contractors succeeded in weakening the False Claims Act during World War II, claiming it would hold up the production of matériel — but during the 1960s and 1970s, as trust in government plummeted, several high-profile whistle-blowers, both within and outside government, reminded Americans just how much of a key role whistle-blowers could play.

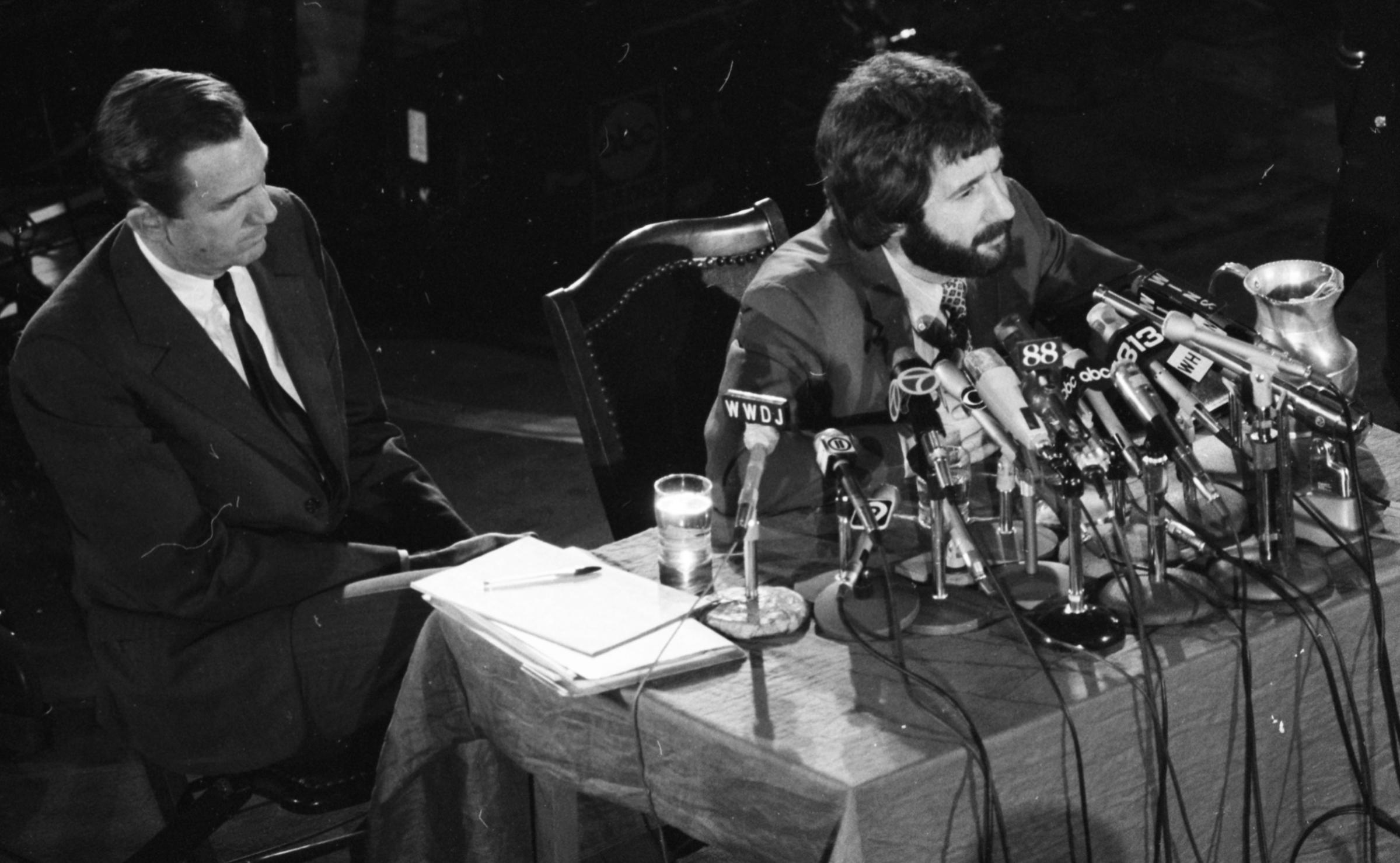

A. Ernest Fitzgerald testified that Lockheed Martin was overcharging the government by billions of dollars. Frank Serpico exposed bribery in the NYPD. Karen Silkwood, who was killed in a car crash en route to deliver documents in the case, exposed hazardous conditions at the Kerr-McGee plutonium plant in Crescent, Okla. Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers, secret documents revealing that the government was mismanaging the Vietnam War and lying about it, to the New York Times. And of course, the Watergate informant known as “Deep Throat,” Mark Felt, helped bring down Richard Nixon’s presidency.

Hollywood movies about whistle-blower cases, such as 1976’s All the President’s Men and Meryl Streep’s 1983 turn in Silkwood, further increased awareness and public respect for whistle-blowers.

Reacting to sweetheart deals being cut between the government and defense contractors at the height of the Cold War, Congress strengthened the False Claims Act in 1986. Penalties for making false claims were increased, requiring offenders to pay triple what they overcharged the Treasury. Since then, over $60 billion in ill-gotten tax dollars have been returned to the Treasury via whistle-blower complaints filed through the law.

While the False Claims Act mostly pertains to people in the private sector who work with the government, it’s been more complicated for people in the intelligence and national security field to come forward. The Intelligence Community Whistleblower Protections Act of 1998 established the process that the whistle-blower who raised concerns about Trump’s call with the Ukrainian president went through, in that he filed a complaint that was routed to the U.S. Inspector General’s office.

However, despite having “protections” in the name, people who work at national security agencies who have gone through this process have not always felt as if this process is a secure one for them. For example, in 2002, Tom Drake and Bill Binney were part of a group that reported to the Inspector General’s office concerns that government efforts to monitor Americans’ Internet activity would invade their privacy. When news came out related to their allegations, the FBI raided their houses.

Tom Mueller interviewed about 200 whistle-blowers for his book and found that the “overwhelming majority” haven’t been able to work again because they were blackballed in their industries; perhaps the most famous recent American whistle-blower, Edward Snowden, is still in exile in Moscow. “It’s career suicide,” he says, arguing the treatment of whistle-blowers in real life is more of how society views them, versus the praise they receive at a distance or on a screen. He argues there’s a two-faced attitude towards whistle-blowers in American society.

“We have a completely dual attitude,” he says. “We applaud them in the theater but we go home and allow industries and governments to destroy them, their careers, their health, their lives.”

And yet their influence is undeniable.

TIME made three whistle-blowers Person of the Year for 2002 — WorldCom accountant Cynthia Cooper and Enron executive Sherron Watkins for exposing corporate fraud, and FBI agent Coleen Rowley for her memo to then FBI Director Robert Mueller about the mishandling of security threat warnings before 9/11 — for risking everything “to bring us badly needed word of trouble inside crucial institutions” and because they believed “that the truth is one thing that must not be moved off the books, and for stepping in to make sure that it wasn’t.”

“We shouldn’t need a special word, some weird legal status, for doing the right thing, for doing our jobs. The fact that we have that [term] is a bad sign. Whistle-blowing is democracy,” Tom Mueller says. “It’s freedom of speech. It’s independence of conscience — the kinds of things the framers had in mind.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com