Whether or not they knew it, the crowds who cheered President Donald Trump at a July 17 rally in North Carolina by chanting “send her back” in reference to Rep. Ilhan Omar were part of a long American story of telling certain people they don’t belong in the country. The chants — which even many of his fellow Republicans called racist— came days after Trump sparked outrage by tweeting that Omar and three of her fellow Democratic Congresswomen of color, all of whom are Americans, should “go back” if they have problems with the U.S. On Monday, Trump continued to take aim at them. And this story isn’t just taking place in the federal government: on Friday, a black Georgia state representative claimed that a man at a grocery store told her to “go back” where she came from.

These words stood out for being part of a very particular anti-immigrant strain in American history: the idea that people who are deemed “inferior” or “other,” even if they were born in the U.S., are not really American and thus ought to leave. The contours of the “in” and “out” groups have evolved — though white Anglo-American Protestants have dominated the former — but the idea has deep roots.

One moment that particularly illustrates this dynamic, historians say, came nearly 200 years ago, amid a U.S.-backed effort to send free black Americans to Africa.

“That’s a very concrete example of telling people who were born in this country that they don’t belong here and they have to ‘go back,'” says historian Kunal M. Parker, author of Making Foreigners: Immigration and Citizenship Law in America, 1600–2000.

This idea began to take shape practically as soon as the United States became home to a significant community of free black people, which was not long after the American Revolution. There were efforts to abolish slavery in some places and new laws that made it easier to free enslaved people, but the idea that free people of different races could live together as Americans was terrifying to many elites. Slave rebellions in the South furthered the panic. One of the “solutions” that emerged among those who felt that way was that, even though slavery had been an institution in North America for centuries and many African Americans had no personal ties to Africa, freed people could leave.

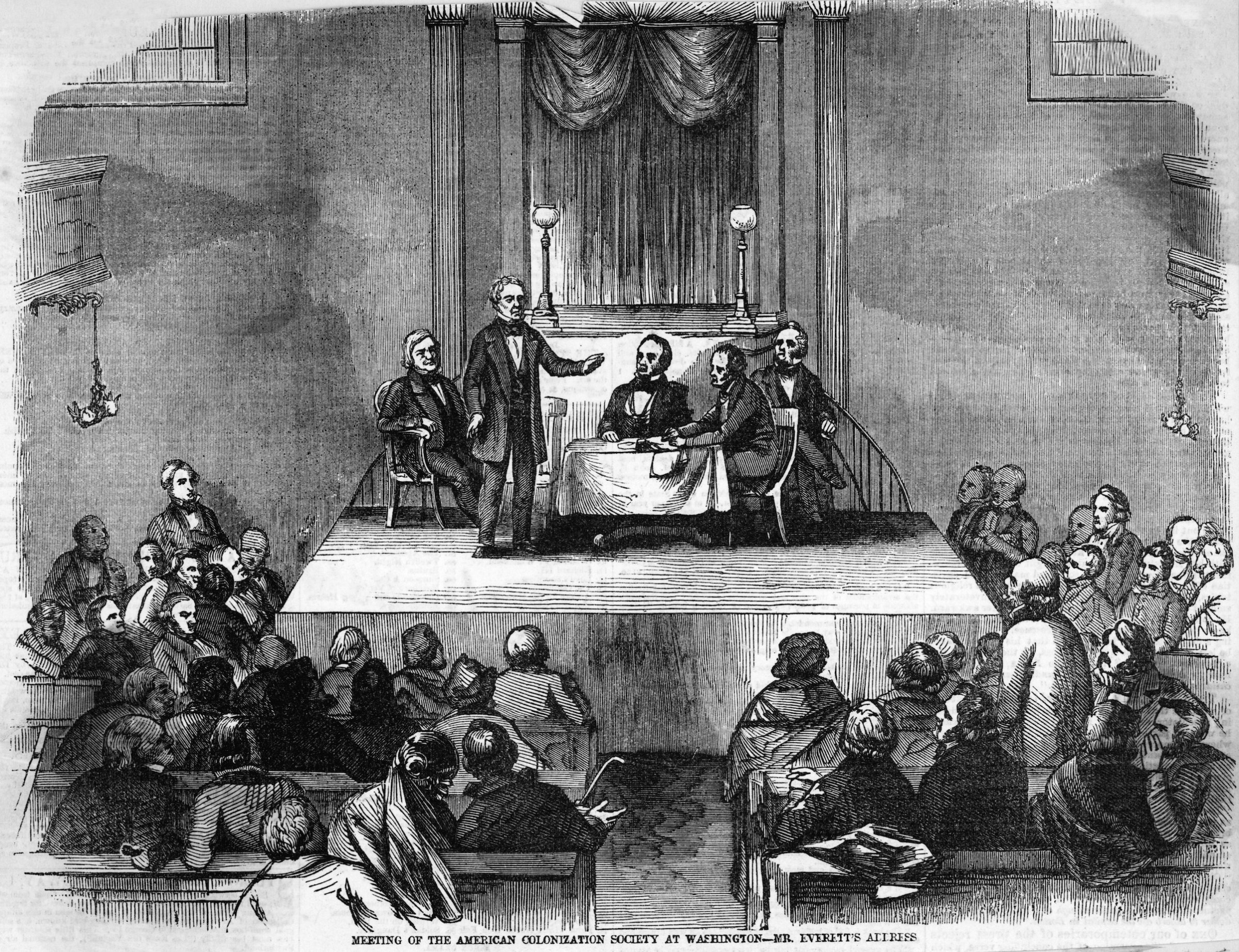

As James Ciment details in Another America: The Story of Liberia and the Former Slaves Who Ruled It, in 1816, the American Colonization Society (ACS) was founded in the tavern of the Davis Hotel in Washington, D.C. The ACS built on ideas articulated by Thomas Jefferson, who five years after the Declaration of Independence wrote that people who’d been freed from slavery should be “removed beyond the reach of mixture” from the country.

The ACS had an example to go off: Freed slaves from Britain had settled in Sierra Leone in 1787, and it became an official British colony in 1808. In 1815, the black Philadelphia shipping magnate Paul Cuffee — who felt that Africa offered the best future for his fellow free African Americans — paid $5,000 to send 38 African Americans (including 20 children) there.

To some African Americans, the idea of leaving the United States and starting fresh somewhere closer to the land from which their ancestors had been taken was inherently appealing. But the society’s members often focused more on the removal aspect than on the fresh start. They were mostly white political elites, including Daniel Webster and U.S. Senator Henry Clay, who at an early meeting exposed the idea’s underbelly when he declared that the ACS could “rid our country of a useless and pernicious, if not dangerous portion of its population” while spreading enlightenment to “a benighted quarter of the globe.” A Supreme Court Justice, Bushrod Washington (George Washington’s nephew), agreed to serve as its symbolic President. State legislatures in Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia started appropriating funding to encourage colonization, and some slave owners made manumission contingent on leaving the country, according to Parker.

In 1820, 88 free black settlers and three ACS representatives sailed to Sierra Leone begin the search for West African territory that would be a fit for the society proposed by their group. Around December 1821, ACS traded some muskets, gunpowder, tobacco, rum, shoes, beads and soap (worth nearly $300 at the time) for the land that would become Liberia.

ACS chose that name in 1824, based the Latin word for “free,” and named its capital Monrovia for the American president at the time of its founding, James Monroe, who was instrumental in securing a $100,000 federal grant for the project. The emigrants came to be known as “Americoes.” Virginia-born Joseph Robert Jenkins, who had emigrated in 1829, became Liberia’s first governor in 1841, and its first President in 1847 after he declared its independence from the American Colonization Society.

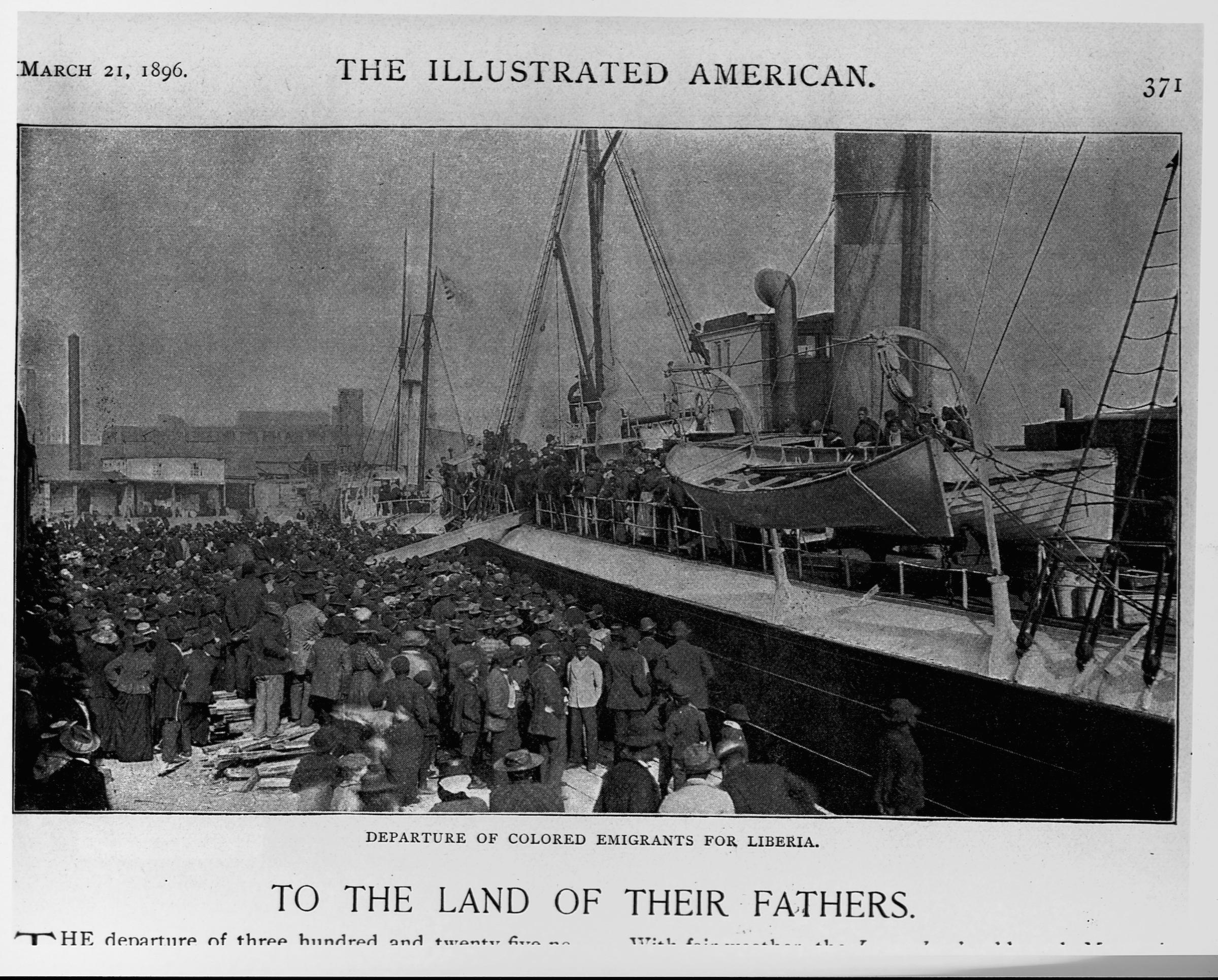

By the Civil War period, about 15,000 free African-Americans emigrated to Liberia, but most were against the initiative.

“They saw it as a removal,” says Mae Ngai, a historian of immigration at Columbia University. “Some African Americans did support this idea because they thought they’d never be able to be included in America, and [moving there] was a choice made out of a determination that they would never be welcome in the U.S. even though they were born in the U.S. But the majority of African Americans did not support this.”

In 1852, the African-American abolitionist Martin Delany wrote, “We look upon the American Colonization Society as one of the most arrant enemies of the colored man, ever seeking to discomfit him, and envying him of every privilege that he may enjoy.”

Free black people actively resisted efforts to push them out, even as some Southern states enacted laws that codified them as foreigners, no matter where they were actually from. In 1838, the Tennessee Supreme Court upheld a statute that blocked them because “every free State has a right to prevent foreigners going to it” and in 1859 the Mississippi Supreme Court ruled that “free negroes are to be regarded as alien enemies or strangers prohibiti.”

That said, back then, “most blacks [in the U.S.] are not even aware there is a Liberia,” says Greg Carr, Chair of the Department of Afro-American Studies at Howard University. “In the Deep South, on plantations, these people are worried about day-to-day survival.”

Liberia wasn’t the only place that the U.S. politicians tried to implement this idea. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln thought Central America would make more sense, logistically. The historian Michael Vorenberg has argued that Lincoln “made a political calculation” that emancipation and colonization went hand in hand to “accommodate racist sentiment against the Emancipation Proclamation” by offering anti-abolitionists the possibility that they wouldn’t have to deal with slavery’s aftermath. On Dec. 31, 1862, he approved a contract that would appropriate federal funds to settle some 5,000 black men, women and children, on Vache Island, off the coast of Haiti; the experiment was abandoned less than a year later. Frederick Douglass later cited a meeting in which Lincoln pitched colonization to a black delegation in August 1862 and “strangely told us that we were to leave the land in which we were born” as a moment that “strained” black people’s faith in Lincoln.

After the Civil War, the ACS shifted its focus to education and missionary work, but fizzled out after 1919. “After enslavement, they still need that black labor force,” Carr explains. Those in power in the South no longer wanted these formerly enslaved people to leave, but instead wanted to keep them around and oppressed.

But the scars of that period remained. In the late 19th century, when southern states were making it harder to vote by adding poll taxes and literacy tests, the resulting disenfranchisement of black voters was likened to being deported to Liberia. And when Ralph Ellison, the author of Invisible Man, wrote a 1970 essay for TIME about “What America Would Be Like Without Blacks,” he looked to that period too:

The slaveowners and many Border-state politicians wanted to use it as a scheme to rid the country not of slaves but of the militant free Negroes who were agitating against the “peculiar institution.” The abolitionists, until they took a lead from free Negro leaders and began attacking the scheme, also participated as a means of righting a great historical injustice. Many blacks went along with it simply because they were sick of the black and white American mess and hoped to prosper in the quiet peace of the old ancestral home.

Such conflicting motives doomed the Colonization Society to failure, but what amazes one even more than the notion that anyone could have believed in its success is the fact that it was attempted during a period when the blacks, slave and free, made up 18% of the total population. When we consider how long blacks had been in the New World and had been transforming it and being Americanized by it, the scheme appears not only fantastic, but the product of a free-floating irrationality. Indeed, a national pathology.

And the American psyche wasn’t all that was scarred. Its unusual origins have also left the country of Liberia at a disadvantage. In a 1947 article marking its 100th anniversary of Liberia’s independence, TIME noted that the country “never had much of a chance” and “got its independence in 1847 chiefly because nobody was looking.” The settlers who came to Liberia in the 19th century displaced the people who already lived there and exploited them for labor.

“That’s the legacy of Liberia that continues to this day, the whole tension of putting people who weren’t from that region into that region because they happened to be black,” Carr points out. Even today, as was apparent during the Ebola outbreak in 2014, Liberia’s “early legacy of inequality,” as TIME put it then, still affects its society.

And that history of inequality is still grappled with in the U.S., too, as part of the country’s more than 240-year-old struggle to live up to its ideals and its founding declaration that “all men are created equal.” In that, Carr says, the story of this colonization effort can serve as a warning.

“Either we’re going to have an American experiment that’s truly radical in world history or it’s going to dissolve,” he says. “The ACS is really about America’s ongoing attempts to control this experiment, and you can’t control the human experiment.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com