Outside the closed world of the Kremlin and the Russian prison system, few could have anticipated the death of Alexei Navalny, Russia’s leading dissident, in an Arctic penal colony on February 16. It came as a devastating shock to the revolutionary movement he led and, more acutely, to his close friends and family. In the days that followed, the only relief from the despair among his allies came from the announcement by his wife, Yulia Navalnaya, that she would take up his cause and continue his struggle against the regime of Vladimir Putin.

About a month later, Navalnaya sat down with TIME for an interview in Vilnius, Lithuania, where her husband’s activist organization, the Anti-Corruption Foundation, has set up its base in exile. It was the first interview she has given since her husband’s death. Over the course of two hours, she described how her family experienced this tragedy, how she decided to take up Navalny’s struggle, and what she intends to do in leading the opposition movement amid the sweeping crackdown against dissent in Russia and the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine. Below is a transcript of the conversation, which took place on April 1. It has been condensed and edited for clarity by TIME.

Read the interview in Russian here

When did you last see Alexei alive?

I last saw him a few days before the start of the war. The year was 2022, around the 15th or 16th of February. He was still in Pokrov, the first prison where he was sent. His new trial had just started, the one that would result in a sentence of nine years. We weren’t allowed to have that many visits, because he was always in the punishment cell. But when they did allow it, we always tried to make it so his parents and our children could come as well. And we would have lunch all together. Then toward evening they would leave, and Alexei and I would stay together for two more days.

What do you remember from that visit?

The Olympics were on TV, the figure skating events, and there were a few of our Russian girls who were leading. They were competing against each other. Alexei didn’t really like to watch sports. But because these were important competitions, I forced him to watch figure skating with me.

At the time, the Russian military had positioned around 200,000 troops at the border with Ukraine, ready to invade. What did you say to each other about that?

Of course we talked about it. The world, the West, the United States were warning everyone, saying that the war was about to start. But honestly, it felt more like Putin would just go around scaring people. It seemed to me that it would be in his style to bring things to the brink, to scare us, and then withdraw and go back.

Read More: Yulia Navalnaya and the Future of the Russian Opposition

Why were you so sure he would not launch the invasion?

I thought that Russians — that Putin would not dare take such a step, because no one in Russia would support it. It’s like with our family, where we have close relatives on that side, close friends. There are families in which the mom is Ukrainian and the father is Russian, or the other way around. It was impossible to believe that Putin would take such a risk. It was so common to have family on both sides.

Alexei also has family in Ukraine, is that right?

Yes, of course, Alexei’s dad is from Ukraine.

After the invasion started, did you have a chance to talk to Alexei about it? Perhaps on the phone?

We didn’t have the ability to speak to him by phone. Maybe once or twice, very briefly. But talking on the phone is not the same in prison. I understood that the call is being recorded, and next to him are several prison guards. Honestly, these conversations are not about much. It’s just to hear the voice of the one you love. Once in the summer, during my birthday, he managed to get permission for a phone call with me. But it didn’t work out. He called and said: "Hello, hello," and then it cut off. That was in July. It was the last time I heard him telling me hello.

In December, he was transferred to a new prison north of the Arctic circle. The negotiations to win his freedom through an exchange of prisoners with the West — were they already underway at the time?

I knew about these negotiations. I just can’t talk about them in detail, because I wasn’t deeply immersed in them. But I knew they were ongoing.

He was at the Arctic prison camp for only around two months before his death. In that time, you were able to exchange a few messages with him through his lawyers. Did anything stand out to you in those last messages, some foreboding, some hint of what was to come?

Probably not. Now, when you look back and try to search for clues, you can find your way to some interpretations.

For example…

Honestly I’m not ready to talk about such details yet. With hindsight, I have started to think about such things. But at the time, with Alexei, we always had a very happy, friendly relationship. So even if one of us wrote a sad letter, the other would say, "Hey, come on, you sound really down."

One thing we often wrote about is that, when he had the good fortune for music to play on the radio, instead of Putin’s speeches, he would write to tell me that this or that song is about me. The last song he wrote to me about — that song was just so sad. I wrote him back, "No, come on, that’s going too far." I laughed about it.

What was the song?

I’m sorry, I won’t tell you. [Laughs.] But songs in general were rare. In the punishment cell, there was a speaker directed at him, and more often they would play these speeches from Putin for months on end. Alexei would describe this with a sense of humor, as he did with everything. But this really is a form of torture.

What did that last song tell you about him?

It didn’t tell me much. I was surprised, because he was always so upbeat. Even the day before his death, we saw him in court, and he was laughing. He never was in a depressed mood. But I think he had it very hard. These last two years, they were really torturing him. He was starving. They didn’t allow him to buy food in the commissary.

They did not allow him to receive care packages. He had a minimal sum that he could spend in the commissary store. They were really torturing him with hunger. That is probably the most horrible thing I think about when I imagine his existence in the camps.

Let’s talk about that awful day, February 16, when we all learned of his death. I would like to ask you to remember that day, and to describe it.

I arrived in Munich the night before, for the Munich Security Conference. It wasn’t my first time there. I had a few meetings planned. I woke up in the morning and was getting ready for some meetings. The first one was around noon, and then I glanced at the phone. These notifications appeared, and I saw the headlines were about Alexei Navalny. That was nothing out of the ordinary, because Alexei had court hearings almost every day. So I got used to getting news alerts that start with the name Alexei Navalny. Then I saw the third word. [Pauses.] The third word said he’s died. Then, for about five seconds, I turned away, and only then I registered what that word means. I was in my room. I was alone at the time.

Read More: Column: Alexei Navalny Is With Us Forever Now

What were you thinking?

It’s difficult to believe such a thing. It’s not that I didn’t believe it. But I felt that we had to get to the bottom of this. These reports were coming only from Russian official sources. I would call them propaganda outlets, practically all of them. So I thought that, for a start, we should figure things out, and only then could we start crying and worrying.

It's hard to describe what I felt. It’s a feeling I can’t describe, and I hope never to feel again in my life. First I wanted to pull myself together. Lyosha’s mom called me and she said that she’s flying to the prison colony. I agreed she needed to go there. We wondered whether all this might turn out to be wrong, some mistake.

Lyosha’s mom behaved like a true hero there. She is a real hero. There is nothing more horrible in life than going around for a week, knowing that your son has been killed, and you cannot collect his body. The people responsible for giving you his body are making a mockery of you. She was being blackmailed. They were saying they would not give her the body, that they would bury him there at the camp. It was terrible. Alexei’s mom bore all this with dignity, and she got the body.

A few hours after you learned of Alexei’s death, you addressed the Munich Security Conference. Many people were amazed to see you so poised in such a moment. How did you decide to make that speech?

We got a call from the organizers of the conference, and they invited me to speak. In that moment, I had no doubts. I said without hesitation that I’m going to speak. But it was scary. The Munich conference is probably the most famous political event in the world. Many of the world’s high-ranking officials take part. When they speak, they usually have time to prepare. I was in a different situation. I came out and said what I said. I wasn’t expecting to make an address from the main stage.

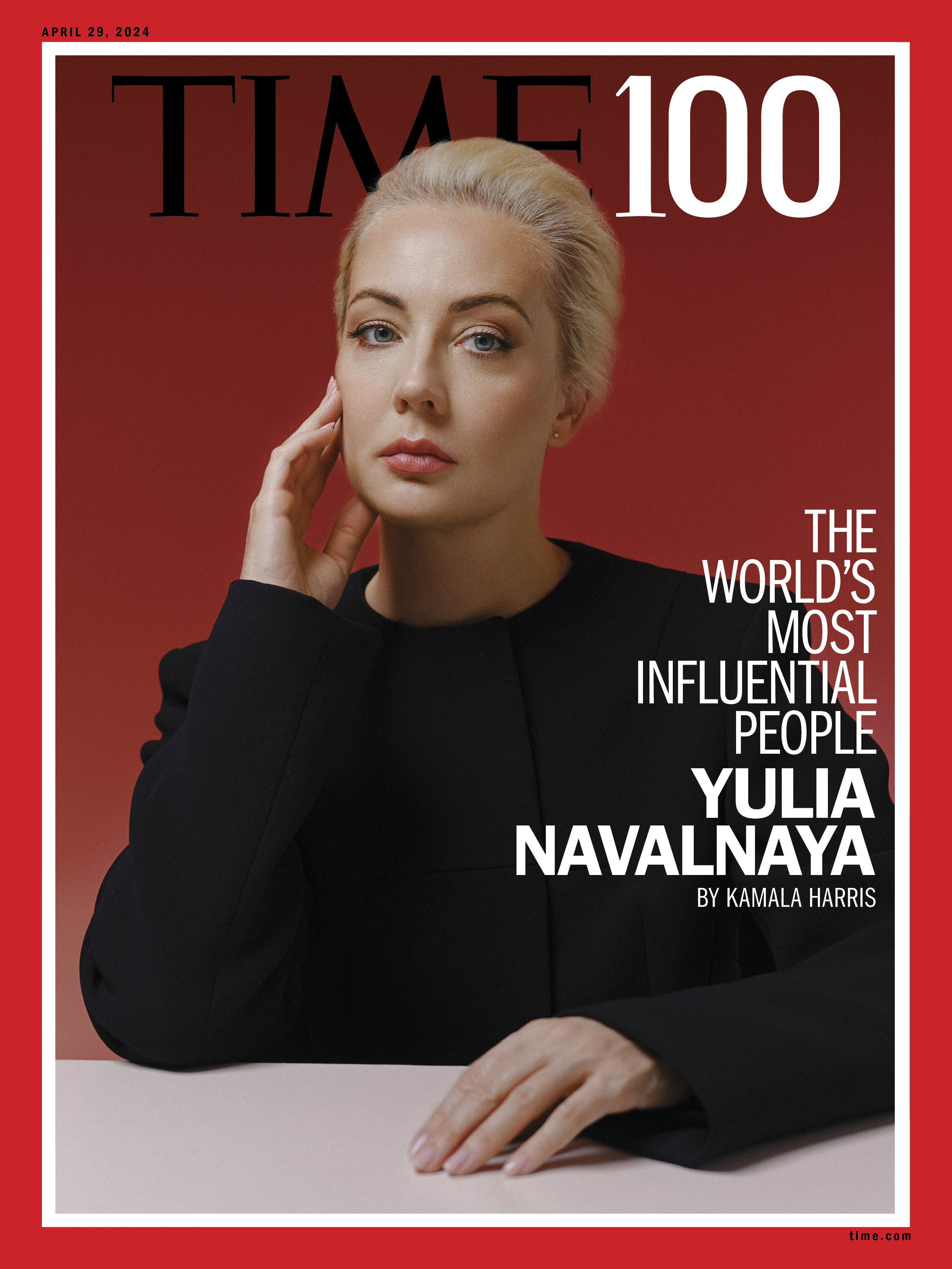

Read Vice President Kamala Harris’ TIME100 tribute to Yulia Navalnaya here

Among the guests in Munich that day were some of the negotiators trying to free your husband in a prisoner exchange. Putin had made clear that he wanted the return of a Russian prisoner held in Germany: Vadim Krasikov, a hitman for the Russian intelligence services. When you arrived in Germany on February 15, were you intending to talk to German officials about these negotiations, about this exchange involving Navalny and Krasikov?

That possibility was under consideration, but [in Munich] no special talks related to that were scheduled. Like I said, I knew about these negotiations, but I didn’t participate in them. At that moment I understood that these agreements have been made.

Do you believe these events were connected? The prisoner-swap negotiations and the death of your husband?

I deeply believe that someday we will not have only theories, and we will know for sure who did this, how and why. But right now this is among the most realistic theories. For normal people, it may sound strange. But for a person who starts wars, who threatens the world with nuclear weapons, it is reasonable to expect that he would say one thing to one group of people, another thing to others, all while preparing to carry out a murder at the moment when it is most convenient for him. Then he merely gave the order when he felt the time was right.

I think there’s a high likelihood that Putin never intended to free Alexei from the first day he put him in prison... Once he understood that the trade would need to involve Alexei, he decided right away to kill him. Putin didn’t care. For him, killing is not a problem at all.

To what end?

To show that, 'We will not give you Alexei, but you will give us Krasikov for someone else.' That may have been it. When he understood that Krasikov could only go free if we have Alexei, then he decided to demonstrate that they will not get Alexei under any circumstances.

Who are "they"? The German authorities? The Americans?

I don’t know in detail how these negotiations worked. I just mean the collective of people who were trying to get Alexei out. Simon, I’m sorry, I didn’t expect that we would discuss the swap with you for so long. I understand these are very interesting issues. It’s just a shame that there’s so little to discuss, because nothing worked out. And the result turned out to be so tragic.

Read More: How Tech Giants Turned Ukraine Into an AI War Lab

Then let’s move on. On Feb. 19, you published a video saying you would continue Alexei’s work. Do you believe this was his wish for you?

No. Honestly, I don’t want to make guesses about this. Otherwise, in difficult moments, I may start to wonder: What if this wasn’t his wish? What if he wanted the opposite? I don’t want to think about this. We did not talk about it. I just thought that this can’t be allowed to happen. If they think they can kill Alexei and that’s the end of it, they are wrong.

I saw how many people feel this loss very, very deeply, and I really wanted to support these people, to give them some kind of hope. And most of all, I want the Kremlin and its officials to understand: if they killed Alexei, then I will step up. If they do something to me, another person will come. There are very many people who are against the ruling authorities in Russia, against the regime, and I don’t doubt that even if they kill a great many of these people, more will appear to take their place.

Did anyone try to talk you out of your decision to continue his work?

No. Then again, I didn’t really consult with anyone.

About a week after your husband’s death, you met with President Biden in San Francisco. What stands out in your memory from that meeting?

We talked for more than an hour. He devoted as much time as he could to us. It wasn’t just condolences. It was a really good, kind, warm conversation. Maybe it had to do with the fact that, in his life, he also suffered huge personal loss, and he can understand better than most what it means, without warning, to lose someone so close to you. Even if that person is sick, even if that person is in prison and you believe that this could happen, you always believe while that person is alive that things will turn out fine.

Did you talk with Biden about sanctions, or other ways that the U.S. should react to Alexei’s killing?

We did talk about sanctions. I offered President Biden help in finding certain assets. The Anti-Corruption Foundation is very good at this. When it comes to sanctions, that’s very important. And I think the West totally does not hear us when we say that we need more targeted sanctions against Putin’s inner circle.

Such sanctions really hit Putin’s power, whereas the sanctions that affect random people, like the ones that were imposed by the E.U. and Great Britain after Alexei’s killing, they are quite laughable. These are sanctions against the rank and file. Yes, there were some generals among them, but also rank-and-file prison officials in the village of Kharp, in the Yamalo-Nenets region. Such sanctions are not only an insult to Alexei’s memory. They are an insult to the dignity of those who impose them. It’s disrespectful to the people who impose these sanctions, because they should fully understand that none of these officials have ever been abroad. They will never go abroad.

Read More: From Beyond the Grave, Russian Dissident Alexei Navalny Challenges Vladimir Putin at the Polls

Most people who serve in Russian law enforcement do not even have a passport. They can only travel to a few countries, like Egypt, Vietnam, I’m not even sure about Turkey. Sanctions that prohibit them from visiting London, or freeze any real estate they may have abroad, it’s just laughable. Sanctions need to target Putin’s friends and members of his inner circle. Everyone knows that they really value their glamorous, wealthy lifestyles. Half of them have yachts and planes. If you sanction them, they will start to think about the fact that Putin is not letting them continue living their lavish lives. So maybe they should stop supporting him. Of course I understand that Putin has scared these people on a political level. Yes, some may be scared, but others may think that their yacht is more important than their fear.

Why doesn’t the West impose these sanctions? What do they tell you when you present these arguments?

The problem, Simon, is that there is a big difference between the first and second part of your question. When I tell them these things, they say: ‘Yes, yes, of course, we need to impose these sanctions.’ But why they don’t impose them is another question, and it’s a good one. I’ll tell you an example.

Last summer, I was in Europe to receive a prize on Alexei’s behalf, and I met a senior European official. The first sentence he said to me was, ‘Well, we are still afraid that, after Putin, things will be worse. What if someone else comes, and it will be even worse?’ Honestly, I can’t understand what European officials have to fear after Putin attacked Ukraine, after he marches around the border of the European Union, after all the proven cases of poisoning in the Great Britain, after his threats to use nuclear weapons — I can’t imagine what could be worse. Yet this senior European official told me: 'What if it gets worse?'

So the West is afraid these sanctions could lead to Putin’s downfall?

They are probably afraid he will push the red button and use nuclear weapons. But that has nothing to do with sanctions. Putin is behaving in such a way that no one knows what he will do tomorrow, or even today. He has so little trust in his own circle that even they cannot guess what he will do next.

Was President Biden’s position the same as this European official?

One of the points we discussed is that it would be great to set up a working group that would include our team of investigators, led by Maria Pevchikh, who has been working on this for many years and has uncovered not only where the real estate [of Putin’s inner circle] is located, but also how that real estate is registered under their relatives, associates, businessmen tied to Russian officials. In that sense our organization can be very useful in passing the kinds of sanctions that will be supported inside Russia.

The existing sanctions don’t work. They only help the Kremlin’s propaganda say: 'Look at what the collective West has done to us! They’ve imposed sanctions!' Sanctions need to be imposed not against Russia, but against the Russian authorities, against Putin personally.

What was Biden’s answer to that argument?

He agreed, and he gave me the contacts of an official that I have passed along to our team.

In your speech to the European Parliament on Feb. 28, you said that tens of millions of people in Russia do not support the war. The opinion polls in Russia don’t seem to bear that out. How can you be so sure of that?

Of course I’m sure. Almost everyone opposes the war, they just do so in different ways. There is a great number of anti-war people who remain in Russia. Only a small number went abroad. The majority have nowhere to flee. This is their country. They will remain there regardless. Some of them are resisting, and that number is of course not in the tens of millions. But many people are against all of this. It’s just that, well, not everyone is ready to be a hero. So they go on living their normal lives.

But, as we’ve seen, at any opportunity, they are ready to go out into the streets, whether it’s to line up for any anti-war candidate for an election, or during the “Noon Against Putin” event. That’s to say nothing of the funeral of my husband. That funeral turned into a kind of march, a demonstration. In the first day, there were around 40,000 people there. That’s one day, one place, near one subway station. All of them are obviously against the war. They were shouting against the war.

I’ve spoken about this with President Zelensky and his team, and they don’t believe this. Their views on this have evolved over time, but by the end of 2022, they had concluded that this is not just Putin’s war. It is Russia’s war, and it is wrong to go around looking for what they call "good Russians."

"Good Russians" is a very bad expression. I think they just don’t want to look for these anti-war Russians. But such Russians exist in Russia. It’s just hard to expect them to go out and protest the war, because, like I’ve said, not everyone is a hero. People are ready to take on different kinds of struggle. It’s important to support these people, and I think ignoring them is a mistake of the Ukrainian government.

Regular Ukrainians understand that not all Russians are against them. But when it comes to the Ukrainian government, I think it would be right for them to remember these people. This is clearly not Russia’s war. This is Putin’s war. Of course there is a very aggressive, pro-war minority. It stands out, but it’s very small. Putin does his best to promote it. He points to them and says, "Look, everyone is like this!" But that’s not true. Most people, for different reasons, want an end to this war.

Do you see that as one of your goals, to find common cause with the Ukrainian leadership? To cooperate with them?

It’s hard for me to answer this question right now, because it does not only depend on me.

Before we move away from the topic of Ukraine, I have to ask you about the State of the Union. On March 5, the Washington Post reported that First Lady Olena Zelenska would not attend President Biden’s speech, because you would be seated next to her. Can you comment on this?

I honestly learned about it from the Washington Post. Before that I didn’t know that she had also been invited. I think it’s a shame if what the Washington Post wrote is true, that she did not come because of me. I didn’t even know she would be there.

To be honest, when the last presidential elections took place in Ukraine, one of the reasons I supported Zelensky and hoped for his victory was that I really liked his wife. She appealed to me a great deal.

On March 12, one of your husband’s closest friends and allies, Leonid Volkov, was attacked in Vilnius by a man wielding a hammer. What signal did you take from the way this attack was carried out?

What’s important about this attack is that, two meters from Leonid’s home, some people were waiting for him with a hammer and a can of pepper spray. His wife was in the house with their little kids. One child had just turned 2 years old. And some people were stalking him at the door of their home. Today they attacked Leonid, tomorrow they’ll break into the house. And what will they do with the children?

It's some kind of horrific, scary situation. Nobody knows what they will think of doing next time. But I always try to underscore this: Do not expect Putin to make any well-considered decisions. He makes decisions alone, or with a very small inner circle, and no one can guess what he will make up his mind to do next.

Did that attack change the security measures you take for yourself?

We have thought about some new security protocols. To be honest, I don’t really like to go around with a bodyguard. But as you saw, I had one when I arrived here today. A young man, a bodyguard, I don’t even know what to call him. [Laughs.] Alexei and I never had security, and I think I inherited some of that courage, that cavalier attitude from Alexei. But when you’re too cavalier, you can make a wrong move. So, for now, my colleagues have asked me to go around with a bodyguard.

Ever since the attack on March 12?

Yes, because these people were not caught. We don’t know what will come next, and taking such risks is definitely not a good idea.

Around the time of the attack, you wrote in an op-ed article that the world should treat Putin not as a president, but as a mafia boss, a gangster. What does that mean in practice?

The problem is that the West thinks of Putin as a politician. But he has long ceased to be a politician. He is the head of an organized crime group. All of his inner circle are criminals. They have committed war crimes, they have violated laws, they have stolen a whole lot of money from the people of Russia, all while keeping the people of Russia in poverty, and the problem of poverty in Russia is only getting worse.

The only reason we can’t see this is that Putin learned to work well with propaganda. The people have come to believe that without Putin things could get worse, or that the West is to blame for all their problems, not Putin. Unfortunately, these views exist in Russia. But they exist because Putin keeps people in poverty, and their ability to get alternative sources of information is very limited in all those distant towns and villages far from Moscow. They only watch TV. Television is available everywhere. And the television tells them this: "Ukraine is horrible. The Americans want to conquer us. The West only dreams of conquering us." And unfortunately, if you hear this every day, some people start to believe it. Others go a little crazy, not in the sense of being sick, but in refusing to watch anything at all. They start to say that only their private lives interest them.

This is the result of an enormous effort on Putin’s part. He devotes a great deal of time and resources to this. That’s why we at the Anti-Corruption Foundation devote so much time to bringing people information. Yes, far from Moscow, people don’t have the money for Internet access. But it’s still very important to inform people. If you don’t want to watch TV, you become a totally apolitical person, which is also very scary.

So one of your key goals is to maintain these channels of information into Russia?

It’s not just one of them. It’s the most important. So that people in Russia remember — they know that they have not been forgotten. They have not been left in the grip of this dictator, this beast. I know — I can see from all the recent demonstrations, that a great many people are afraid to take part in certain events. But most people are willing to go out into the streets in some easier format, and I do not wish by any means to divide Russians who live inside Russia, and those who have been forced to leave Russia. I really hope that one day they will return to Russia, so we can work to build the beautiful Russia of the future that Alexei dreamed about.

What do you make of the election-day demonstrations known as Noon Against Putin?

I see that event as highly successful. It’s very difficult at a time of war, at a time when people can be jailed or sent to prison for holding a sign or liking a post — it’s very hard to find the moment people are ready to go out and not be afraid. This demonstration gave them that change, it was the right thing to do. It doesn’t matter at all how these people voted. Obviously, Putin would count the votes however he wanted. But now everyone is talking about the fact that people stood in line for hours. In Berlin, several of my friends did not get a chance to vote, because they arrived at noon, and at 8:00 p.m. the polling place closed. They were still standing there. This feeling people had inside Russia, and outside, that you came and you saw people just like yourself, people who are against Putin, against the war. It’s obvious. Even though Kremlin propaganda claimed that all these people came to vote for Putin, it's clear they were all against him. Now they know that at every polling place where they went at noon to vote, they are not alone.

Order your copy of the 2024 TIME100 issue here

When you voted in Berlin, you entered the Russian consulate, which is technically Russian territory. Were you worried about being arrested there? How did the Russian officials react to your presence?

I don’t know what they do to Russian consular workers when they are trained, but I can’t say they were mean to me. They were like robots: "Hello, sit down, cast your ballot, and get out." I told them all, "Goodbye and thank you." They answered, maybe a bit spooked. I didn’t feel any kindness, but I don’t blame them. I guess it’s linked to the fact that the consulate has cameras everywhere. They think: What if I smile at her, what if I look at her the wrong way. Still in their souls I think Russian consular workers are good.

Was I afraid to go into the consulate? Probably not. But while I was standing in line, I felt so much support that it was not hard to go inside. It was a pleasure to go. I became friends with the people who were waiting in line around me. One of them joked that I might be detained once inside. They told me they would fight to pull me out if that happened. We laughed about it.

It's a joke, but there was a risk that you would be arrested. The consulate is Russian territory.

Yes, the thought enters your mind, because you don’t know what Putin and his authorities will do next. These worries exist. You asked me before how I make certain decisions. Often I feel that I have no choice. I must do this. It’s the right thing to do, and after that I don’t think it over too much. I just do it. [Laughs.]

How did you vote?

I spoiled my ballot, and wrote: Navalny.

Some observers have remarked that you have a better chance than Alexei of uniting the opposition. Would you agree? And whom do you see as your greatest ally within the movement?

Above all, my allies are all Russians, no matter where they are, inside Russia or abroad. These are the people who supported Alexei. They write me endlessly with messages of support, and their support means the world to me. They are the ones I can rely on.

As for uniting the opposition, the last demonstrations showed that it’s not hard to unite around a good, collective action. That is the main source of unity.

When we published a cover story about Alexei in January 2022, our headline was, “The Man Putin Fears.” Do you think Putin fears you?

I’m not sure how to answer that. Honestly, I don’t care whether he fears me or not. I am going to do what I’m doing. I am going to do what’s right. I am going to fight against Putin. Putin is my enemy. He killed my husband. He killed him in a cowardly way, killed him at a time when he was already in prison. That shows his cowardice. So I think your headline was exactly right.

But in light of the campaign they have launched against me in recent months, always inventing, generating news around me, it’s clear that some propagandists sold him on the theory that they need to fight against me. So that pressure will grow. The Russian state always loves to find another enemy.

So we’ll see. I can’t promise you that I’ll never be afraid. [Laughs.] Right now, I’m definitely not afraid. I’ve lived under this kind of pressure for at least 15 years. They watched me, they watched my children. When we were on vacation, people took pictures of us from a boat. They followed us around in cars. This was in Karelia, in Russia.

I’ve learned not to pay attention to them. People can get used to anything. I’m not afraid of such things. There are unpleasant moments, but there’s nothing to be done about that. As for whether he fears me, well, time will tell.

Read More: The Story Behind TIME’s Interview with Alexei Navalny

In your video address on Feb. 19, when you declared your intention to continue Navalny’s work, you asked Russians to share in your rage. What did you mean by that?

Rage does not mean hatred. Rage is when they kill the one you love. I didn’t doubt that Alexei has a great many supporters, but these endless pledges of help that people were sending me, the kind words, the endless lines of people who come to his grave with flowers even now, a month and a half later still impressed me. I’m very grateful to these people. And I think that’s what Putin should be afraid of. Not me, but the people, people who remember Alexei and who share in my rage, in my pain, in the grief from what we have lost, and also in the hope and the desire to live in a normal, democratic country.

For many, you are now the symbol of that hope. How does that feel?

It’s very nice to hear, but that’s also a lot of responsibility. I will try my best not to let them down.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com