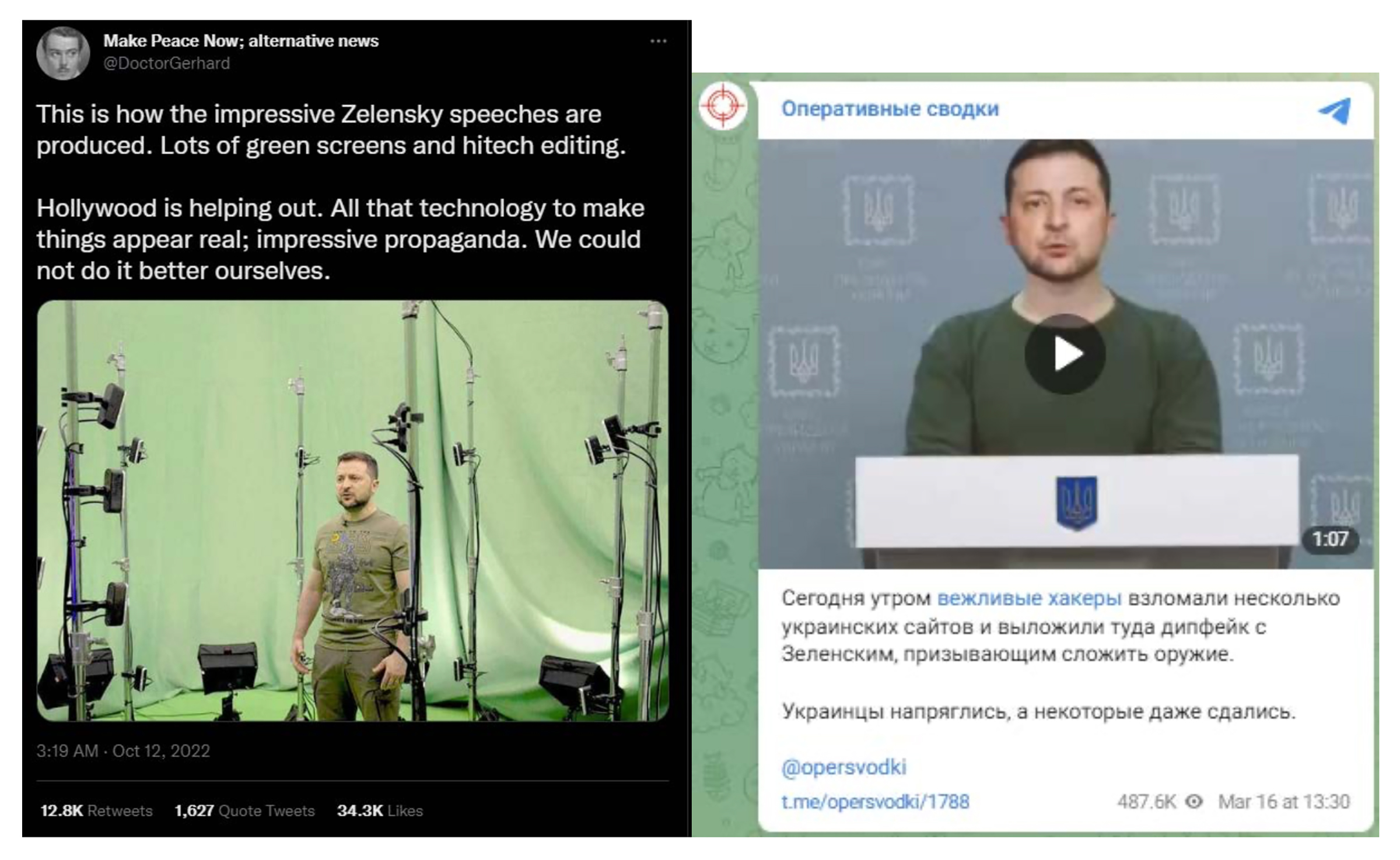

Three weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine last Feb. 24, a video appeared on a Ukrainian news site that seemed to show President Volodymyr Zelensky imploring his fellow countrymen to stop fighting and urging soldiers to lay down their weapons.

“There is no need to die in this war,” he seemed to say in the video, which was widely circulated on social media and appeared briefly on Ukrainian television with a news ticker suggesting that he had fled the country. “I advise you to live.”

The video—a crude deepfake that had been posted by hackers—was quickly taken down and debunked. It was dismissed by the real Zelensky as a “childish provocation,” and roundly mocked online as an example of Russia’s desperate and often cartoonish attempts to spread fake news. But researchers say the deepfake is just one example of a barrage of disinformation, manipulated imagery, forged documents, and targeted propaganda unleashed by Russia and pro-Kremlin activists that may have had a significant impact on audiences over the last year of war.

“Changing people’s minds and positions is much harder than simply sowing doubt or fear,” says Andy Carvin, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, which has tracked Russian hybrid warfare activities since 2015 and on Wednesday released a pair of reports analyzing the Kremlin’s information warfare before and after the invasion. “It’s one of the reasons why Kremlin information operations focus so much on essentially generating chaos, causing contagion, causing a loss of morale, or just getting people simply confused about what’s true and what’s not.”

Read More: How Putin Is Losing at His Own Disinformation Game in Ukraine.

Over the past year, the Kremlin and its allies used a dizzying array of strategies to defend its actions, seed doubt about news from the ground, and push misleading or false narratives to undercut support for Ukraine. Denied the easy victory they had hoped for, Russian officials working to erode global trust in Ukraine as a reliable partner. “To defeat Ukraine on the battlefield,” the report argues, “Russia needed to strangle all sympathy and support for Ukraine as well.”

In pursuit of that goal, the Kremlin targeted everyone from Ukrainian citizens to right-wing groups in the U.S. and Europe, countries taking in Ukrainian refugees and those supplying crucial aid, and potentially sympathetic audiences in Africa and Latin America, as well as domestic audiences in Russia itself. Russia’s techniques for spreading these narratives included the use of fake accounts, manipulated imagery like deepfakes, forged documents, and videos with fake news tickers purporting to be from respected brands like the BBC or Al Jazeera. In other cases, operatives simply aimed to increase mistrust in foreign audiences about the credibility of Ukraine’s government and the effectiveness of its military.

While many of these efforts may seem inept to digitally savvy Western observers, it’s a mistake to depict Russia as “losing” the information war, says Carvin, who oversaw the project. “There really isn’t a single information war going on,” he says. “Russia and Ukraine are fighting multiple battles, but Russia has the resources to create customized messages to different audiences all over the globe…And in some parts of the world, their messages resonate better than others.”

Before Putin ordered tens of thousands of troops into Ukraine, the Kremlin spent years seeding false narratives to justify military action. When the invasion began, the effort kicked into overdrive. Ukrainian researchers were taken aback by the volume of false information in the war’s opening weeks.

“It very hard [to know what to believe], especially when you hear the bombs outside of your window,” says Ksenia Iliuk, the co-founder of LetsData, a non-profit that uses artificial intelligence to analyze hostile information operations. In the first month of the invasion, her team identified about 35 new, unique pieces of Russian propaganda or disinformation narratives per day.

Ukrainian officials treated the digital space as a front line in the war from the start, setting up teams and processes to verify the facts in all updates posted on official channels as a way to pre-empt any challenges to their credibility. “In a way, we are trying to protect our brand,” Ukraine’s Minister of Digital Transformation, Mykhailo Fedorov, told TIME last March. “Our brand as one of an honest nation and an honest people trying to tell the truth.”

Read More: ‘It’s Our Home Turf.’ The Man On Ukraine’s Digital Frontline.

Social media is Ukrainians’ primary news source—surpassing television in 2020, according to a recent survey—and the Russians targeted popular apps with false narratives meant to demoralize the population, create panic, and undermine trust in Zelensky. Much of the information battle was fought on Telegram, a messaging app that surged in popularity due to its largely unmoderated platform which allowed raw footage of the war to be widely disseminated. The structure of the app made it easy to build massive propaganda channels that spread fake photos and videos to millions of followers.

As part of an effort to target Telegram, Russia co-opted popular fact-checking formats. It created a host of multilingual channels, like one named “War on Fakes,” which “verified” or “fact-checked” allegations to support pro-Kremlin narratives and defend the Russian military’s actions. The original Russian-language channel amassed more than 750,000 followers on Telegram, and its website translated its content into Arabic, Chinese, English, French, German, and Spanish, which was then amplified by Russian embassies and other government channels, according to the report.

Russia combined these efforts with more traditional intimidation tactics, including dropping leaflets in Dnipropetrovsk describing what residents should do if there was an explosion at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, military training flights that set off air-raid sirens, and rumors—fueled by Putin himself—that speculated about the potential use of nuclear weapons.

Read More: How Telegram Became the Digital Battlefield in the Russia-Ukraine War.

Some of these narratives hit their mark, breaking through on a global scale. False allegations spread by the Kremlin that Ukraine was utilizing U.S.-funded research labs to develop bioweapons were widely amplified by prominent U.S. right-wing voices last summer. The right-wing channel One America News ran segments spreading the Kremlin’s conspiracies that the Russian strike on a maternity hospital in Mariupol was a “false flag.”

The Russian government blocked access to Western social media platforms inside their own country—even designating Meta an “extremist organization”—criminalized independent reporting on the invasion, and passed a law imposing up to 15 years in prison for spreading intentionally “fake” news about the war. It also targeted the Russian diaspora abroad. In Europe, the Kremlin carried out “multichannel, full-spectrum disinformation campaigns” with tailored messages for different countries. For example, it used statements by high-level Russian officials, inauthentic social media accounts, and doctored documents to spread claims that Poland was planning to occupy parts of western Ukraine. In France, pro-Kremlin accounts amplified false claims of widespread reselling of Ukrainian weapons on the black market and hyped up fears that Europeans would freeze in the winter without access to Russian gas.

Pro-Kremlin media also continued to pour resources into Africa and Latin America, exploiting historical distrust in the West and anti-imperialist sentiments. “By maintaining these information operations at a global scale, Russia has successfully prevented international consensus rallying behind Ukraine at a level that is often presumed in the West,” the report found.

As the war enters its second year, the Kremlin is likely to continue to use these techniques to influence ongoing debates about whether to continue to supply Ukraine with weapons and funding, the report suggests. Russia may also continue to take advantage of the sympathy of China’s global media ecosystem towards their interests, according to researchers.

“Russia’s reputation as unparalleled information warriors has taken a beating in the West, but this view is by no means universal,” the report’s authors found. “The more accurate assessment is that the impacts of information operations related to the war will have a much longer shelf life, well beyond the confines of the current conflict.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Vera Bergengruen at vera.bergengruen@time.com