In Russian custom, the soul of the dead is believed to remain on earth for forty days, finishing its business among the living before it moves on to the afterlife. Surviving friends and relatives often spend this period in mourning and reflection. But the loved ones of Alexei Navalny, Russia’s leading dissident, did not have much freedom to abide by this custom after he died in an Arctic prison camp on February 16.

For them, and especially for his wife, Yulia Navalnaya, the days and weeks that followed his death rushed by in a blur of studio lights, airport terminals, hotel rooms and video calls. Somewhere in that time, between consoling their two children and being consoled by them, she met with President Joe Biden in San Francisco and addressed the European parliament in Strasbourg. She accused Vladimir Putin of killing her husband, and she implored the Russian people to help her get revenge. Along the way, to the surprise of many of her husband’s followers, Navalnaya took on a role she had never occupied before — no longer the first lady of the Russian opposition, but now its figurehead.

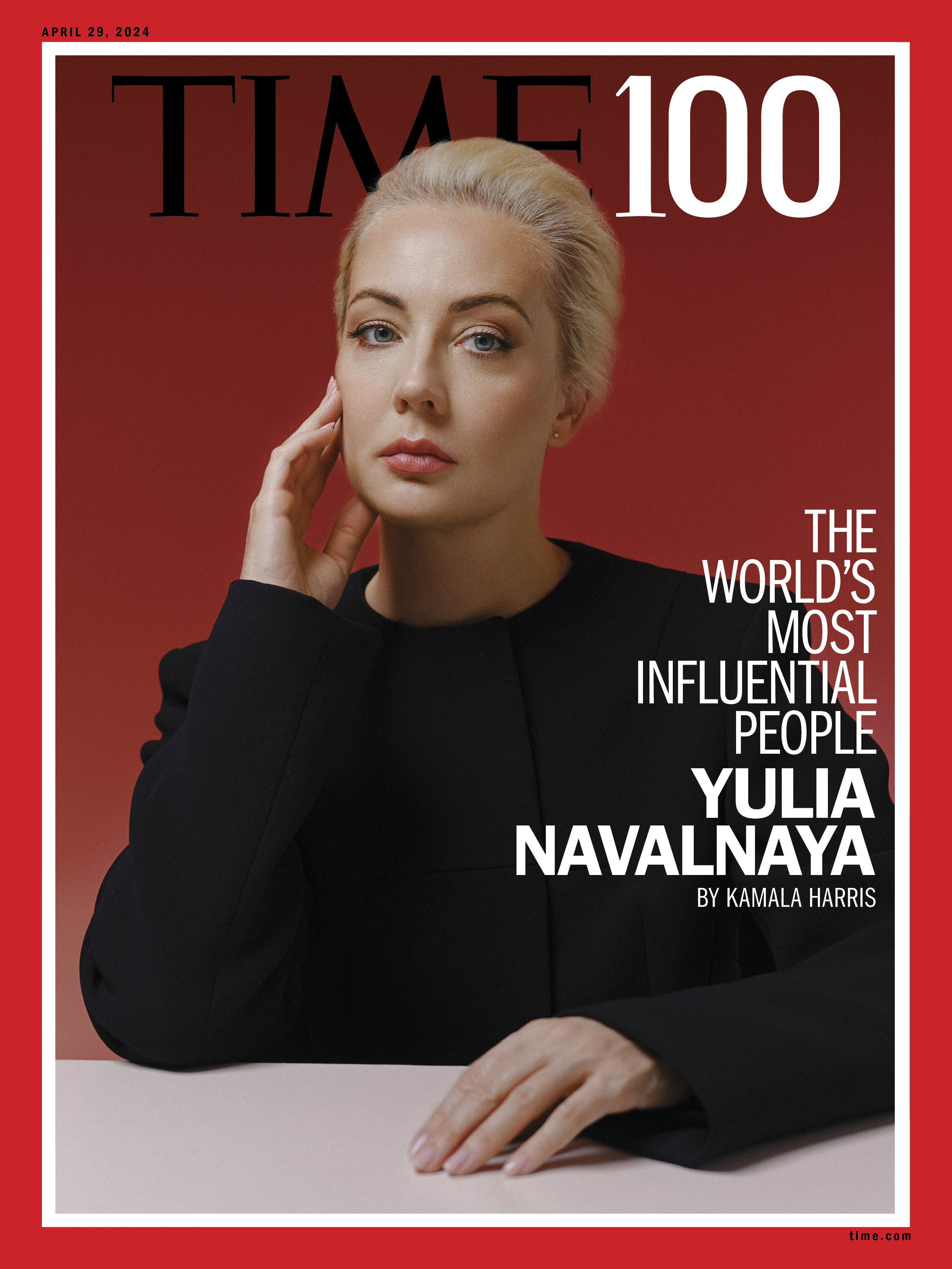

It was in this new role that she agreed in early April to an interview with TIME, a little more than forty days after her husband was killed. The location took some time to figure out. Her family’s exile from Russia has forced her to move around in recent years. But we agreed to meet in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, where her husband’s activist organization has its base of operations. At the appointed time, Navalnaya arrived in the company of a bodyguard, striding through the parking lot in a stark black suit and patent-leather heels.

Read More: 'Share My Rage.' Read the Transcript of Yulia Navalnaya's First Interview Since Her Husband's Death in Prison

Some of her husband’s friends and allies had warned me that she could come off as distant and aloof. One of them unkindly referred to her as a “snow queen.” But as we sat down to talk over coffee, her memories of Navalny often made her smile as she recalled his sense of humor, the lightness with which he faced the darkest moments in his life. Not once in those two hours did her voice catch in her throat, and only a few times did she allow the pain of the previous weeks to show in her eyes. “There has been so little time to think, to plan, to process,” she admitted. “But we have to keep working, to keep moving forward.”

For her husband’s followers in Russia, the way forward looks far from clear with him gone. It took well over a decade of campaigning and activism for Navalny to earn his place within the opposition movement, as the only dissident to pose a genuine threat to Putin’s rule. Even after his imprisonment in 2021, Navalny continued to run his revolutionary network, to campaign against corruption and to spread his promise that Russia would one day become a normal European democracy. That hope dimmed after Navalny’s death, and for many it was extinguished.

His wife could see that in the messages she received after his death. “I saw how many people feel this loss very, very deeply,” Navalnaya says. “And I really wanted to support these people, to give them some kind of hope.” Her best chance of doing that, she says, was to step into his role and continue his struggle. So that is what she decided to do. In a video address three days after his death, she fought back tears as she told the people of Russia: “Share my rage – the rage, anger and hatred toward those who dared to kill our future.”

Read Vice President Kamala Harris’ TIME100 tribute to Yulia Navalnaya here

Many assumed that this decision had been Navalny’s wish. But his wife says they had never talked about it. There was no succession plan, not even after Navalny was nearly poisoned to death in 2020. “It was not discussed,” she says in our interview. His allies always clung to their faith that, sooner or later, Navalny would outlive the regime and emerge from the prison to replace it.

That vision of Russia’s future died with Navalny, and his team has now set out to imagine a new one. In the weeks that followed his death, TIME interviewed over a dozen of his friends, allies, critics and fellow dissidents, traveling to find them in four of the countries where they have gone to escape Russia’s system of repression. Many of them described feeling paralyzed by grief and despair in Navalny’s absence. Most agreed that his wife stands the best chance of succeeding him and carrying his banner. But some wondered what she could achieve from exile, cut off from her supporters, with little if any space to operate in Russia itself.

The main risk, one of them told me, was that Navalnaya turns into what Russians sometimes call a “parquet politician” — attending summits and ceremonies in Western capitals, accepting prizes for her courage and calling for change, all while the Kremlin continues to dismiss her as a demagogue in exile, detached from the lives of the people she intends to save. In our interview, Navalnaya acknowledged this risk. At times it seemed to worry her more than my questions about the physical danger she faces in challenging Putin so openly.

Her core mission, she says, is to remain in touch with her supporters inside Russia, even though she cannot see or touch them. “Most of all, I want the Kremlin and its officials to understand: if they killed Alexei, then I will step up. If they do something to me, another person will come,” she says. “There are many, many people who are against the ruling authorities in Russia, against the regime, and I don’t doubt that even if they kill a great many of these people, more will appear to take their place.”

Navalnaya last saw her husband almost exactly two years before his death. At the time, he was imprisoned not far from Moscow, in Penal Colony No. 2, in the town of Pokrov, where regulations sometimes allowed the wives of inmates to come and stay with them for a couple of days. Small apartments were set aside for such visits on the prison grounds, each equipped with a kitchen, a bed and a TV set.

For the visit that would turn out to be their last, Navalny’s parents came along, bringing bags full of groceries and food they had prepared. Among his favorites was green borscht, a kind of soup with sorrel that, according to Navalny, has a “cult following” in their family. After lunch, his parents drove back home to Moscow, while his wife stayed with him for two more nights, watching figure skating events from the Beijing Olympics and talking for hours about politics.

It was the middle of February 2022, and the debates on every news network concerned the Russian troops that stood poised to launch an invasion of Ukraine. Navalny believed these armies to be part of an elaborate bluff, a way for Putin to extract concessions from the West. “Time and again the West falls into Putin’s elementary traps,” he wrote in a letter to TIME that January. “It just takes my breath away, watching how Putin pulls this on the American establishment again and again.” He argued instead for sanctions targeting the personal wealth of Putin and his closes allies.

Read More: The Story Behind TIME’s Interview with Alexei Navalny

Putin had not been bluffing. On his orders, Russian warplanes launched a relentless barrage of missiles across Ukraine on the morning of Feb. 24, 2022, and a ground assault involving thousands of military vehicles soon began its march on Kyiv.

Navalny, during his court hearings and in his prison letters, condemned the invasion once it was underway, calling it a “war built on lies.” But he stuck to his long-held belief that corruption, not imperialism, serves as the foundation of Putin’s regime, and he continued calling for targeted sanctions against the assets of Putin’s inner circle. By seizing their wealth, Navalny argued, the West could cause fissures in the Kremlin elites, thus speeding the collapse of the regime that started the invasion.

Many Russian billionaires did face sanctions in the U.S. and Europe, but they did nothing to change Putin’s behavior. Instead, the war intensified, and Russia’s descent into dictatorship accelerated. What remained of its independent media shut down under the laws of wartime censorship in Russia, which imposed prison terms of up to 15 years for public criticism of the military’s actions. Even lonely picketers in the streets of Moscow faced arrest and prosecution. One man was sentenced to two years in prison after his 12-year-old daughter drew an anti-war picture in school.

Hundreds of thousands of Russians fled the crackdown, including many of the well-heeled urbanites who had always formed Navalny’s base of support. The few who stayed had no luck sparking an anti-war movement. “We did resist,” one of Navalny’s closest friends and allies, Ilya Yashin, wrote to me in a letter from prison about a year after the invasion started. He listed a few isolated cases of dissent that had quickly been repressed. In Yashin’s case, the state sentenced him to more than eight years for posting a video about Russian war crimes in Ukraine.

“Those who remain in Russia,” Yashin wrote, “are living with the rights of hostages. Many of them don’t support the war, but they remain silent, afraid of repressions.”

Navalny’s children were already in exile by the time the invasion started. His son Zakhar was enrolled in a boarding school in Germany. His daughter Daria studied at Stanford. Their mother shuttled between them, staying in touch with her husband’s activist group, the Anti-Corruption Foundation, which set up its headquarters in Lithuania. When I visited their offices in Vilnius at the start of 2022, they had just finished building a small production studio to film their livestreams for viewers in Russia. Millions of them tuned in, and the Foundation’s broadcasts soon became a vital source of news and analysis about the war in Ukraine.

Read More: How Tech Giants Turned Ukraine Into an AI War Lab

But its focus remained on the work that made Navalny famous in Russia: investigating acts of corruption within the elite, exposing the yachts and villas that Putin’s courtiers tried to hide around the world. Their findings, released on YouTube as bingeable videos, routinely attracted millions of viewers. But, to escape arrest, the Foundation’s activists inside the country were forced to go underground in 2021, when the state declared them an “extremist group,” a legal status similar to that of ISIS or Al-Qaeda.

Navalnaya, then living in Moscow to remain close to her husband, had never played a prominent role in the Anti-Corruption Foundation. She did not take part in its day-to-day operations and held no position its management. The group’s leading members saw her as a friend, an inspiration and a sounding board, capable of divining how Navalny would feel about a decision even when he could not be there to help them make it. She was not even deeply involved in their negotiations to win Navalny’s freedom. “I knew about these talks,” Navalnaya told me. “But I didn’t participate in them.”

Those talks had started in early 2022, when Navalny’s allies set out to arrange a prisoner swap, inviting Russia to trade him for someone locked up in the West. The dissident in charge of this effort at the Anti-Corruption Foundation was Maria Pevchikh, a scrappy and relentless activist who led the group’s investigative unit before becoming its chairwoman in 2023. For two years, Pevchikh traveled across the U.S. and Europe to help facilitate the swap, approaching intermediaries who could make offers and pass messages to the Kremlin. The only one whose name she would reveal on-the-record was Henry Kissinger, the former U.S. Secretary of State, who was known to have an open line with Putin and other senior officials in Moscow. “He did not prove very useful,” Pevchikh told me, noting that Kissinger died in November, months before a deal was struck.

The deal’s main impediment, Pevchikh says, was the dearth of high-value Russians in U.S. custody. Eventually, they landed on a candidate in Germany. Vadim Krasikov, a hitman for the Russian intelligence services, was serving a life sentence in Bavaria; he had been convicted of murdering an enemy of the Kremlin in a Berlin park. Putin, who started his career as a KGB spy in Germany, made clear that he wanted to bring the assassin home.

In an interview with Tucker Carlson in early February, Putin hinted that Russian and Western spy agencies were working on a swap involving Krasikov, suggesting that he could be traded for Evan Gershkovich, an American journalist held in Russia on baseless charges of espionage. “They’re keeping in touch,” Putin said of the negotiators. “So let them do their work.” He made no mention of Navalny.

Read More: The Fight to free Evan Gershkovich

But within a week of that interview, Navalny’s allies say they understood from contacts in the U.S. and Germany that the terms of the swap had been set. On February 15, Navalnaya arrived in Germany to take part in the Munich Security Conference, an annual summit of political leaders and military brass from around the world. Pevchikh accompanied her, aiming to meet with some of the officials involved in the prisoner-swap negotiations. That night, when they checked into their Munich hotel, she said, the agreements to free Navalny had been finalized: “I thought he would be home in a week.”

The following day, Yulia Navalnaya was alone in her hotel room when the news alert appeared on her phone. It bore the headline she had always dreaded: Alexei Navalny has died. “For about five seconds, I turned away,” she recalls of the moment she saw his name flash up on the screen. Inertia kept her mind on the immediate cares of the day, the need to get dressed and ready for her meetings in Munich. Then the full meaning of that headline reached Navalnaya, and a wave of pain washed over her. “It was a feeling,” she says, “like I cannot describe, and I hope never to feel again.”

She imagined her husband in that frozen prison colony more than 2,000 miles away, north of the Arctic circle, in a facility known as the Polar Wolf. He had been transferred to that camp in December, and its wardens seemed intent on breaking his will. Guards held him in isolation, deprived him of food and curtailed his contact with the outside world. “He was starving,” Navalnaya told me, looking up at the ceiling to stop her tears from flowing over. “They were torturing him with hunger. That is probably the most horrible thing I think about when I imagine his existence in the camps.”

Day and night, the prison used a speaker to transmit Putin’s speeches into Navalny’s cell, the rambling lectures that the dictator used to justify Russia’s war against Ukraine and to blame the West for provoking it. Once in a while, the broadcasts cut to a music station on the radio, and Navalny made a habit of passing notes to his wife about the songs he heard.

They were usually love songs, but the last one he told her about, in a message smuggled out through one of his lawyers, had lyrics that worried Navalnaya. “That song was just so sad,” she told me, declining to name it. The message gave her the sense that her husband was losing heart, and she tried her best to cheer him. “I wrote him back: ‘No, come on, that’s going too far.’ I laughed about it.” It was the closest thing she had to a warning of what was to come.

Prison officials, in their bland pronouncements of his death, gave no explanation of the cause. They only said he had gone for a walk that morning, collapsed and died. To Navalnaya, it seemed at once impossible and inevitable. The regime had tried to kill him before, once poisoning him with a weapons-grade nerve agent that left Navalny comatose for weeks. Then again, on the day before his death, he had appeared in a Russian courtroom via video link, cracking jokes at the judge and looking healthy.

When she considered Putin’s motives — why kill him now? — Navalnaya found only one theory that made any sense. Putin wanted to stop the prisoner swap, she said, to signal to the Americans and the Germans that they would still hand over Krasikov, the Russian assassin, in exchange for someone else. But they would never get Navalny in return. “Once he understood that the trade would need to involve Alexei, he decided right away to kill him,” Navalnaya told me. “Then he merely gave the order when he felt the time was right.”

The Kremlin’s propaganda outlets barely reported the news of Navalny’s death. But it spread within minutes across the vast diaspora of his supporters around the world, especially the community of activists, journalists and other Russian citizens — at least a million of them — who went into exile after the invasion of Ukraine. Their posts on social media went beyond the anguish and commiseration one might have expected. Their apparent consensus was that, without Navalny, the final strand of hope for Russia had disappeared from the horizon.

The cheerful promise of a “beautiful Russia of the future” — a catchphrase Navalny used for much of his career — had nurtured the faith of a generation of Russians, allowing them to believe that the horrors of life under Putin would not last forever. Now they felt that hope disintegrating. The war in Ukraine, the repressions in Russia, the angst and dislocation that came with living in exile — none of it had any clear end in sight for many of Navalny’s followers.

Read More: Column: Alexei Navalny Is With Us Forever Now

On the night of his death, the voice that expressed these feelings most clearly was that of Mikhail Fishman, an anchor on Russia’s only independent news channel, TV Rain, which broadcasts from a studio in Amsterdam to millions of viewers in Russia and abroad. “Right now we’re in shock,” Fishman said live on air as he struggled to hold back his tears.

“The power of Navalny is that, from prison, he supported those of us who are free, and not the other way around. We were the ones who despaired, while he engaged in politics, made jokes, and showed us the strength of his spirit. Now all of us will need to answer his call not to give up. But how? How can we not give up?”

A few nights later, when we met for dinner in Amsterdam, the answer seemed clearer to Fishman. He had assumed after Navalny’s death that no one could ever take his place. Even if the title of opposition leader would pass to another dissident, someone with clout and experience within the revolutionary movement, the void would remain. But then Navalny’s wife stepped into that void, “and this seemed like the most natural and obvious thing,” Fishman told me. “We all exhaled. The sense of emptiness and hopelessness did not disappear. But it eased when we all saw Yulia.”

In some ways, she had long been preparing for the role. She first met Navalny while on holiday in Turkey in 1998, when they were both 22 years old. Spotting her through the window of a tour bus, the young real estate lawyer was struck by her looks and, as they got to know each other, her intellect and knack for politics. “She was the beautiful blonde who knew every cabinet minister by name,” he later said.

Navalnaya had studied at one of Moscow’s most prestigious universities, where she earned a degree in international economics before going to work at a Russian bank. After their marriage in 2000, and the birth of their daughter the following year, Navalnaya set her profession aside and focused on their family. For a while, she helped her husband’s parents sell the wicker furniture they produced at a workshop near Moscow, while he took up with a clique of activists under the tutelage of Yevgenia Albats, the grand dame of Russia’s dissident circles.

In the early 2000s, Albats ran a supper club in Moscow for young politicians, helping to school them in skills like canvassing and grassroots organizing — concepts that were almost entirely foreign to Russian politics at the time. The club, called Ya Svoboden (“I Am Free”), attracted many upstarts from across the political spectrum who would later emerge as leaders of the opposition movement. Among them, Navalny stood apart. “He was a genius of a politician, the kind that comes along once in a hundred years,” Albats told me. “There has never been a political figure in our history who could speak so well with every stratum of society.”

Albats first met Navalny’s wife in 2006 at his 30th birthday party, which he threw in a basement nightclub across the river from the Kremlin with a banquet table full of food pressed up against the dance floor. Yulia, lithe and imposing, glided among the guests like a revelation, and the host seemed indecently proud to have such a woman for a wife. “I watched them dancing,” Albats recalls. “And I thought to myself: So this is what drives him. He had to prove to her that he was worthy of her."

Now, in taking up his cause, Navalnaya may have advantages that her husband lacked. Within the revolutionary movement, she has a chance to unite the forces of the opposition, moving past the internal feuds and rivalries that cost her husband plenty of potential allies. Among workaday Russians, her story could resonate on a more visceral level, connecting with people in ways that Navalny’s appeals to freedom and democracy did not. “Her power is her motive,” Albats says. “She is out to take revenge for a murdered husband, and that gives her a moral authority that people in Russia can understand.”

In her new role within the opposition, Navalnaya has not been shy about using what may be her clearest advantage: the ability to move around the democratic world, lobbying its leaders and shaming the ones who refuse to stand up to the Kremlin.

A few days after Navalny’s death, she flew to San Francisco to see their daughter Daria, who organized a meeting for them with President Biden. He happened to be in town for a series of fundraisers, and he spent more than an hour with them, Navalnaya told me, offering words of support that struck her as deeply felt. “Maybe it had to do with the fact that, in his life, he also suffered huge personal loss,” she says. Biden’s first wife and their 1-year-old daughter were both killed in a car crash in 1972. “He can understand better than most what it means, without warning, to lose someone so close to you.”

Still, at their meeting, Navalnaya did not miss the chance to advance her cause. She wanted the President to impose sanctions against Putin’s inner circle, and she asked him to involve the Anti-Corruption Foundation in a working group on this issue. Their investigators, led by Maria Pevchikh, have a long track record of uncovering Putin’s wealth and the way his bagmen try to hide it. Biden seemed open to the idea, and he gave Navalnaya the contacts of an official in his administration who could help move the process along.

But so far, both the U.S. and European sanctions imposed after Navalny’s death have been a painful disappointment to Navalnaya and her team. They failed to hit the specific members of Putin’s entourage that the Anti-Corruption Foundation had long identified as targets. Instead, the U.S. sanctioned a state-run firm that issues debit cards to millions of regular Russian citizens, including many political exiles, journalists and dissidents who will now find it harder to access their money from abroad. Russia’s largest shipping company also wound up on the new U.S. blacklist, but its fleet was immediately granted exemptions, allowing it to continue operating without penalties.

In the hope of drawing a stronger reaction from Europe, Navalnaya addressed the European parliament on Feb. 28, telling its members to treat Putin not as a president, nor even a dictator, but as a mafia boss who has seized control of Russia. “You aren’t dealing with a politician,” she said, “but a bloody mobster.” It took nearly a month after that speech for the E.U. to unveil its response to Navalny’s death — a set of sanctions that would seize the foreign assets of 33 people, mostly low-level prison officials who do not earn enough to holiday in Europe, let alone hold assets there. “I wanted to scream,” says Pevchikh, the lead investigator at the Anti-Corruption Foundation. “What the f---!”

Navalnaya, true to form, did a better job restraining her emotions when we discussed this question. When sanctions have so little impact, she told me, “they are not only an insult to Alexei’s memory. They are an insult to the dignity of those who impose them.”

In the month that followed Navalny’s death, his wife and their allies had no time to come up with a long-term strategy. Putin’s re-election to a fifth presidential term was scheduled for the middle of March, leaving his opponents only a few weeks to game out a plan of action for election day.

They knew the regime tended to be vulnerable around the time of these ballots. In 2011 and 2012, Navalny got his best chance to lead a revolution against Putin after the Kremlin rigged two national elections in a row. At least 100,000 people came out on the streets of Moscow that winter to protest, cheering as Navalny called Putin a “scared little jackal” from a stage on Sakharov Avenue.

Read More: From Beyond the Grave, Russian Dissident Alexei Navalny Challenges Vladimir Putin at the Polls

This time, Putin would not allow such acts of defiance. The authorities had signaled that any political protests would be met with overwhelming force and mass arrests. To show that their movement would survive Navalny’s death, the opposition needed a way to demonstrate dissent without putting their supporters in danger of repression.

Navalny’s funeral, held in Moscow on March 1, gave them some hope that it would be possible. Tens of thousands of his supporters turned out mourn his loss, subsuming his gravesite in an enormous mound of flowers. From exile, Navalnaya watched videos of the funeral procession. They convinced her of the latent power of her husband’s followers. “At any opportunity, they are ready to go out into the streets,” she told me. But harnessing that power on election day proved difficult.

In a series of strategy sessions, Russia’s most influential dissidents in exile came up with a plan called “Noon against Putin.” It called on all of Putin’s opponents in Russia to gather at polling stations at noon on election day and line up to vote against him. To make these people look different from other voters, the organizers wanted them to wear the same colors — blue, or white and blue — when they showed up.

But activists working inside Russia said it would be risky to wear matching colors; it could attract the attention of police. “The response we got from our people in Russia was, Are you crazy? That’s too dangerous,” says Pavel Khodorkovsky, an opposition figure living in exile in New York City. “They said, ‘You people in exile don’t know what it’s like for us here.’” As a compromise, some of the organizers suggested that people wear blue “where it is safe to do so.” Practically none of them did.

In the end, the midday flash mobs against Putin still took place on election day, and many thousands of Russians took part, standing in line at noon as instructed by the organizers. But they were indistinguishable from the people who came to cast their ballots for Putin at the same time. On the Kremlin’s television channels, the crowds lined up at polling stations were, predictably enough, cast as enthusiastic supporters of the regime, not as demonstrators against it. From the footage shown on TV, it was impossible to tell the difference.

Even so, Navalnaya felt the action had an impact. “I see that event as highly successful,” she told me. “It’s very difficult at a time of war, at a time when people can be jailed or sent to prison for holding a sign or liking a post — it’s very hard to find the moment when people are ready to go out and not be afraid. This demonstration gave them that chance, and it was the right thing to do.”

On Election Day, Navalnaya was in Berlin, and she lined up to vote at midday outside the Russian embassy in the German capital, standing alongside hundreds of other Russian exiles and supporters of her husband. Some of them worried that she would be taken into custody as soon as she entered the embassy grounds, which legally count as Russian territory. “They told me they would fight to pull me out if that happened,” she recalls. “We laughed about it.”

But, once inside, the Russian poll workers treated her as just another voter. They checked her passport and handed her a ballot. Across the front of it, Navalnaya wrote her dead husband’s name. Then she slipped it into the ballot box and walked back into the safety of the Berlin afternoon.

A couple of weeks later, I arrived at the headquarters of Anti-Corruption Foundation, which stands on a busy street in Vilnius, its door equipped with a facial-recognition system that scans the face of every visitor. My arrival caused a red sign to flash up on the system’s screen. “Stranger,” it said.

Navalny’s press secretary, Kira Yarmysh, soon came down to let me inside. During my previous visit at the start of 2022, their headquarters had looked like a shoestring operation, with beanbags on the floor where activists sat and worked on battered laptops. Now the space looked more impressive, with three fully operational studios and a high-tech control room full of gleaming dials and monitors.

To make room for its staff of around 60 activists, the organization now rents out another floor of the building to house its investigative unit. Millions of people inside Russia watch their broadcasts, which seek to counter the barrage of propaganda that issues from Russian television. In March 2024, their YouTube channels had 19 million unique views, about 75% of them from people inside Russia.

On the day of my visit, the heads of the organization had gathered to plot out the future of their movement, a light rain pattering at the windows of their conference room. Forty-seven days had passed since Navalny’s death, and this was the first strategy session at which his wife occupied the leader's seat, her hair pulled back, her thin frame wrapped in a bulky sweater.

In preparation for the meeting, the Anti-Corruption Foundation had sent out a private call to its activists, asking them to offer ideas for specific actions, demonstrations and other tactics for weakening the regime. Their prospects looked dire that afternoon. Putin had secured another six-year term in office during the March presidential elections; the official tally gave him 88% of the vote.

Improbable as it seems, the result was roughly in line with independent surveys conducted by the Levada Center, a respected pollster that the Kremlin has banned as a “foreign agent.” In a nationwide poll conducted in February — two years into the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and around the time of Navalny’s killing — the agency found that 86% of respondents supported Putin, while only 11% disapproved of his rule.

In our interview, Navalnaya insisted that tens of millions of Russians oppose the regime. “Of course I’m sure of this,” she said when I challenged her on this figure. “Almost everyone opposes the war, they just do so in different ways,” she continued. “Some of them are resisting, and that number is of course not in the tens of millions. But many people are against all of this. It’s just that, well, not everyone is ready to be a hero. So they go on living their normal lives.”

Order your copy of the 2024 TIME100 issue here

In Russia today, even the mildest expression of public dissent requires a degree of heroism and a willingness to sacrifice that few of Russia’s citizens can muster. The goal of the opposition movement in such circumstances, says Navalnaya, will be to offer people ways to resist without facing the wrath of the Russian police state. Participating in a flash mob, signing a petition, writing a letter to an imprisoned dissident — anything that gives people the sense that they are not alone in their desire for political change.

“We have to survive and be ready for any opportunity that may arise,” Pevchikh told me after the strategy session with Navalnaya. She compared it to training for the Olympic Games without knowing when they would take place, or what sport their team would be forced to compete in. Past revolutions have shown that minor flare-ups of public dissent can spread quickly into a conflagration. It is impossible to know where the first spark will come from, she told me — a natural disaster, an act of brutality by the police, a dissident murdered in prison. “But we have to be ready,” Pevchikh says. “Training every muscle, keeping our network alive.”

Navalnaya says she is ready to wait, and to fight, for as long as it takes. Giving up now, she says, would mean that her husband’s efforts, his sacrifices and his death would all have been in vain. At one point in our interview, I asked what Navalny might have made of her decision to take up his struggle. She paused for a moment and looked at her hands. “Honestly, I don’t want to make guesses about this,” she said finally. “Otherwise, in difficult moments, I may start to wonder: What if this wasn’t his wish? What if he wanted the opposite?’” Such thoughts could force Navalnaya to doubt herself, and she cannot afford to do that now. Nor can the movement she seeks to lead.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com