Deepika Padukone never set out to take India to the world. She wanted the world to come to India. As the most popular actress in the world’s most populous country, she’s often asked if she’s going to move to Hollywood. “My mission has always been to make a global impact while still being rooted in my country,” she says on her home turf in Mumbai one humid morning in April, while on a break from shooting India’s first aerial-action film, Fighter.

It’s fitting that Padukone’s photo shoot for this story is happening inside Mehboob Studios, home to some of the most legendary movies made in Hindi-language cinema, from the seminal Oscar-nominated Mother India in 1957 to Padukone’s own Chennai Express in 2013.

The 37-year-old is now a legend in her own right. She has appeared in more than 30 films, won numerous awards, and generated nearly $350 million in global box-office revenues. Today, she is the highest-paid actress in India. Among her legions of fans and nearly 74 million followers on Instagram, Padukone is fondly called the Queen of Bollywood.

Read More: How India’s Record-Breaking Population Will Shape the World

Padukone’s 16-year career is an exception to the rule in Bollywood, the cutthroat Hindi-language film industry, known for prizing youth and continually looking for the next new thing. She suspects this has to do with India’s growing influence in the world. “Indian cinema has transcended borders and Indians are everywhere, so the fame goes wherever you go,” she says.

Buy a print of the Deepika Padukone cover here

Smartphones, streaming services, and social media have helped find new audiences for India’s century-old film industry, which tells about 1,500 stories a year on the screen. At the same time, Netflix and Amazon are also eager to create content that caters to a vast South Asian viewership of nearly 2 billion people around the world.

But they are not necessarily looking only at Bollywood. The recent success of Telugu-language films like Bahubali and RRR has forced the question of whether Bollywood can still dominate the Indian film industry (which comprises many regional languages). All the while, tensions simmer under the surface as a rightward-leaning Indian government monitors the stories India tells about itself on celluloid.

Padukone has been at the crossroads of all these forces, but remains unfazed. After all, she grew up in the enterprising city of Bangalore—known as the Silicon Valley of India, and now called Bengaluru—at a time when India was undergoing economic liberalization. Vijay Subramaniam, Padukone’s agent, says she represents the “typical Bangalore girl”—someone with the world at their fingertips. In Padukone, we see a quiet trailblazer who makes her own rules, all the while embodying the feminine ideal that Bollywood wants to romance. She has emerged from the hopes and dreams of modern Indian women: someone with the utmost freedom to choose how she lives, works, and rests.

Earlier this year, she charmed audiences at the 95th Academy Awards by introducing “Naatu Naatu,” the Oscar winner for Best Original Song from the movie RRR, as a “total banger”; she served on the exclusive jury for the 75th Cannes Film Festival; and she became the first Indian brand ambassador for Louis Vuitton and Cartier. She regularly makes fashion waves during her appearances at global events like the Met Gala and red carpets.

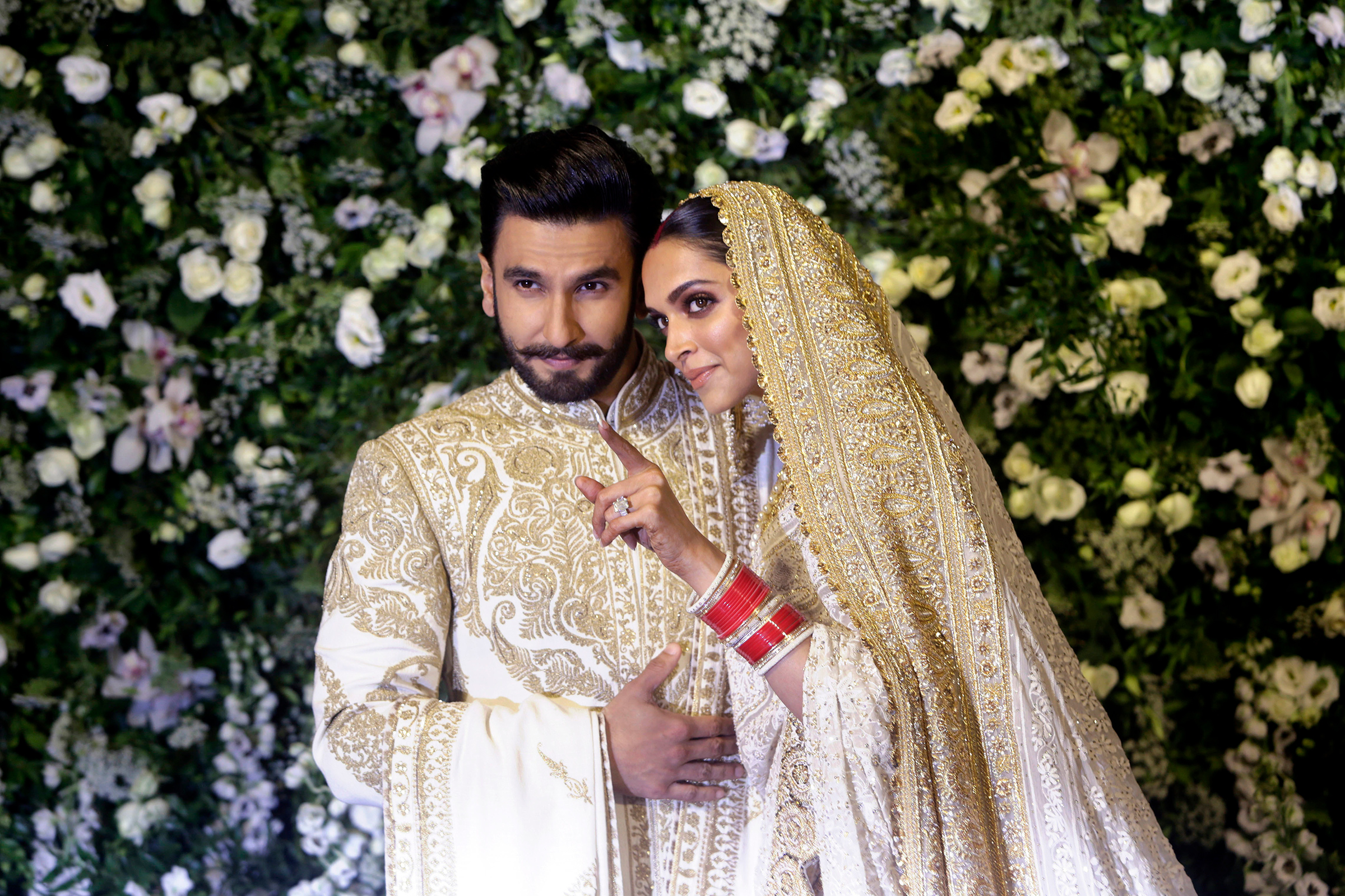

At the shoot, Padukone arrives early, sending the production crew into a frenzy. She’s surrounded by four bodyguards, two agents, two personal photographers, a stylist, makeup and hair artists, and a few more assistants. She poses effortlessly in front of the camera while her personally curated playlist blasts in the background, before her husband—the larger-than-life Bollywood actor Ranveer Singh—stops by the studio to surprise her. He’s interrupting her while she’s at work, but she giggles as the two hold hands for a brief moment.

We head to the Taj Lands End hotel after the shoot, where we enter through a special entrance roped off for Padukone. She wants to gaze at the Arabian Sea while we talk, but the apologetic hotel staff informs her that our private room is on the other side, overlooking a construction site. She’s OK with that, she tells them with a smile, and promptly asks her entourage to leave.

Right now, her life is a lot. Sitting cross-legged on a couch, she contemplates her success. “I didn’t have a game plan for how to get here, but I didn’t see failure on my vision board,” she says.

While she feels fulfilled, she’s also trying to figure out what’s next. “This is India’s moment,” she says. “So how can I marry the best of the East and the West?”

Twenty-one-year-old Padukone parades down a red carpet in slow motion in a wistful romantic sequence. She’s wearing a magenta lehenga-choli, a slick bombshell bun, and full-winged eyeliner drawn to precision with killer dimples to match. It’s her first Hindi film, Om Shanti Om, a campy, madcap spoof of ’70s Bollywood, and Padukone has been cast alongside Shah Rukh Khan, one of the biggest superstars in the world. Nevertheless, she manages to hold her own.

Khan, who co-produced the film, concedes that when he first met Padukone, he wasn’t sure if she could pull off the role. Still, there was a sense that she was on the verge of becoming a star. “Everybody knew it,” he says. Om Shanti Om broke box-office records, and the two have gone on to star in four more films together. In January, they appeared in the spy thriller Pathaan, which quickly became one of the highest-grossing Hindi films of all time, earning $100 million globally. Another collaboration, Jawan, is in the pipeline for release later this year. For Khan, working with Padukone is like “working with family.”

Padukone might have been propelled into the limelight after Om Shanti Om, but she did not have a smooth ride. She was a complete outsider in Bollywood, where simmering tensions over nepotism finally exploded during the pandemic, fueling a reckoning with the advantages afforded to children of actors, producers, and directors who make it in the industry with ease.

Meanwhile, Padukone didn’t grow up thinking she would even become an actor. She was born in Denmark to Ujjala Padukone, a travel agent, and Prakash Padukone, a world-champion badminton player widely credited with putting India on the map in the sport. She played badminton herself on a national level, before leaving home at 16 to pursue modeling on the runways of Mumbai. “From my story so far, there’s nothing that indicates that I would have anything to do with the movies,” she says. “The weird thing is that the few times a year my family watched a movie, I felt a connection. Like that’s where I’m going to be one day.”

Where her debut film lent security and protection—precisely because of its star power—what followed next was a period of mistakes. Her choices were questioned after her next few movies struggled at the box office, and critics saw her acting as mediocre at best. Padukone is quick to accept the criticism, but also points out that “in those years is this girl who was touted as the next big thing, but actually, she was only just figuring her way out.”

Anupama Chopra, a renowned Hindi film critic, says she began seeing an evolution in Padukone’s acting with films like Cocktail (2012), Chennai Express (2013), and Goliyon Ki Raasleela Ram Leela (2013). It culminated with Piku (2015), perhaps her most memorable film, an unconventional comedy heavy on bathroom humor. “You sort of took a step back and thought, oh my god, when did this happen?” says Chopra. “She showed the world that it didn’t matter how pretty you were or how many brands you represented, it was all about what you did in front of that camera.”

Read More: Bollywood Wages a Battle for Hearts and Minds

In 2017, she dipped her toes into Hollywood, starring alongside Vin Diesel in xXx: Return of Xander Cage, an experience that allowed her to push different boundaries. “We speak in English all the time, but to act in English for the first time was so weird,” she reflects.

But her bankability as a star has also been met with fierce opposition, after the conservative Hindu-nationalist turn in Indian politics in the past decade. It first spiked in 2016, when she starred in Padmaavat, a maximalist period drama about a Hindu queen who becomes the object of infatuation of the Muslim Sultan of Delhi. Rumors of a love scene between the two characters drove Hindu vigilantes to light the film set on fire, while an official from the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) offered a bounty of $1.5 million for Padukone’s beheading, horrifying spectators. Local police detained the official.

In 2020, Padukone was spotted standing silently at a student protest against an anti-Muslim citizenship law at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University. Bollywood stars don’t traditionally speak up or protest, so what Padukone did was a rare—and risky—example of a public figure calling out the Indian government, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

And in January came the “saffron” bikini attack over Pathaan—when a Hindu-nationalist minister objected to Padukone’s wearing an orange-colored bikini in a musical sequence. (Orange is considered a sacred color in Hinduism and has been adopted as a symbol for Hindu nationalists.) But Padukone is relieved to say she was genuinely missing in action when the controversy exploded days before the film’s release—she was simply busy at work.

Padukone has remained studiously silent about these controversies, which haven’t deterred her from taking up any roles—including the role of a Pakistani spy in Pathaan. A long pause follows when she is asked about the constant political backlash. Padukone then says, carefully, “I don’t know if I’m supposed to feel something about it. But the truth is, I don’t feel anything about it.”

India may be living in a “polarized cultural climate,” says Chopra, but Bollywood’s real crisis is one of storytelling and content. “Bollywood has lost its place,” says the critic. “It’s a crisis of making better Hindi cinema that connects with the rest of the country,” she continues, nodding to the perception that South Indian movies have, of late, better captured the zeitgeist than those being made in Mumbai.

Last year, Padukone served on the eight-member jury of the 75th Cannes Film Festival, tasked with announcing the winner of the coveted Palme d’Or award. Part of her job entailed “educating everyone around me that Indian movies are more than just song and dance,” she says.

But the opportunity equally made Padukone reflect on Bollywood’s place in the world. She spent the two weeks in Cannes wondering why more Indian films weren’t being showcased on a global stage. “I would say that Hindi cinema has evolved, but we still have a long way to go,” she says. “Why haven’t we had a better moment?”

Until last year, no Indian film had won an Oscar, despite the Indian film industry’s entertaining billions of people. Only three Indian films have been nominated for Best International Feature Film. Now, with the recognition of more diverse content, Padukone says India itself is beginning to realize that its movies are not just limited to Hindi films.

“But I don’t think we should be happy with one Oscar for a song and one Oscar for a documentary,” she says. “I hope we can look at this as the beginning of an opportunity.”

With global superstardom at her doorstep, Padukone is aware of the importance of not losing sight of herself along the way. She is eager to be as authentic as possible—which has also meant being honest with herself, and the world, about her personal challenges.

In 2015, she became one of the few Bollywood actors to come out publicly about her struggle with depression. It surprised everyone around her, especially since she was at the peak of her career, having delivered three hits in a single year. In a country where the stigma around mental health hangs heavy and resources for treatment remain scarce, the admission had every potential to end her career. “But when I spoke about it, it just felt extremely liberating,” she says.

Padukone founded the Live Love Laugh foundation, now headed by her sister, which works with local communities to create awareness and access to mental-health resources. This year, she also launched her own cosmetics brand, 82°E, with the goal to talk about self-care more broadly.

Her actions have opened up conversations about mental health across India, where an estimated 56 million people suffer from depression. “A lot of other celebrities have spoken about [mental health] since then, but more importantly, a lot of noncelebrities have also spoken about it,” says Anisha, her sister. “This is an illness that doesn’t discriminate.”

Read More: Netflix’s The Romantics Aims to Give Bollywood the Homage It Deserves

Padukone is grateful for the support she has received over the years while laying bare her anxieties—especially from her fans. “The beautiful part is that millions of them will probably never meet me, but they’re still on the journey of life with me,” she says. “They understand my body language, my expressions, my silences.”

At the same time, her drive for authenticity has made her conscious of not changing in the eyes of those closest to her. “I will also give myself a little bit of credit that for whatever reason, I’ve been able to keep myself grounded,” she says.

And then there’s her husband Singh, who ripples through Bollywood wearing quirky outfits in public, playing pranks on his co-stars, occasionally posing nude for a shoot—and always making Padukone laugh. The two have just returned from a holiday in Bhutan, where they spent their days doing what Padukone enjoys most: going on walks, sightseeing, and eating. With him, she is her “most vulnerable self,” she says.

Not long ago, Bollywood actresses came with a shelf life that expired as soon as they got married or had children. But that’s changed, Padukone insists. “I’ve never had that experience because [Singh] has always put me, my dreams, and my ambitions first.”

Padukone married Singh in a private celebration in Lake Como, Italy, in 2018. The couple held two intricate Hindu ceremonies—a Konkani ceremony nodding to Padukone’s South Indian roots, and a Sikh ceremony that honored Singh’s North Indian traditions.

The wedding may have been small, but its glamour quotient was high. Padukone tapped India’s most famous designer, Sabyasachi Mukherjee, to dress the couple. Being a Sabyasachi bride was a savvy move for a fashion icon like Padukone—even today, the power couple’s nuptials remain one of the most double-tapped posts on Instagram, inspiring the wedding aesthetics of Indian couples who form a $50 billion-strong wedding market.

The payoff for dominating Instagram, as Padukone has time and again, is enormous, both for her and the companies that hire her. BoF reported the Bollywood star accounted for seven of Louis Vuitton’s top 10 Instagram posts, generating more than 25% of the brand’s $20.2 million in media impact value during the Cannes Film Festival, according to data analytics and marketing agency Launchmetrics. A single Instagram post of Padukone in a floor-sweeping red Louis Vuitton gown garnered more than 2 million likes and generated more than a million dollars in media impact value.

The endorsements go on and on—Levi’s, Adidas, L’Oreal, and Tissot—brands that see Padukone as their gateway to a growing Indian market that was previously thwarted by bureaucracy. In April, Dior hosted its first official show in the country, near the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel. But beyond weddings and luxury clothing brands, India—the world’s most populous nation with 1.4 billion people—will soon become the world’s third largest apparel and footwear market, predicted to be worth more than $83 billion by 2025, according to data from Euromonitor.

If brands want to capitalize on a “new India,” which Padukone calls simply “an emotion,” she knows that stardom has placed her at its fulcrum. “There’s the India with our roots, our heritage, our history, but there’s also a new and young India that’s emerging.”

It’s almost time to go. In a few minutes, she will slip out the special exit with her bodyguards. “It’s these two Indias coming together,” she says, “that I find really fascinating at this moment.”

Correction, May 11

The original version of this article misstated Vijay Subramaniam’s role. He is Padukone’s agent, not her manager.

Styling by Shaleena Nathani; Hair by Yianni Tsapatori; Makeup by Anil Chinnappa; Production by Keyur Lakhani at Imran Khatri Productions

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Astha Rajvanshi / Mumbai at astha.rajvanshi@time.com