The 2022 NYC marathon—the world’s largest—will mark 50 years since a demonstration at the race helped make marathon running more accessible to women.

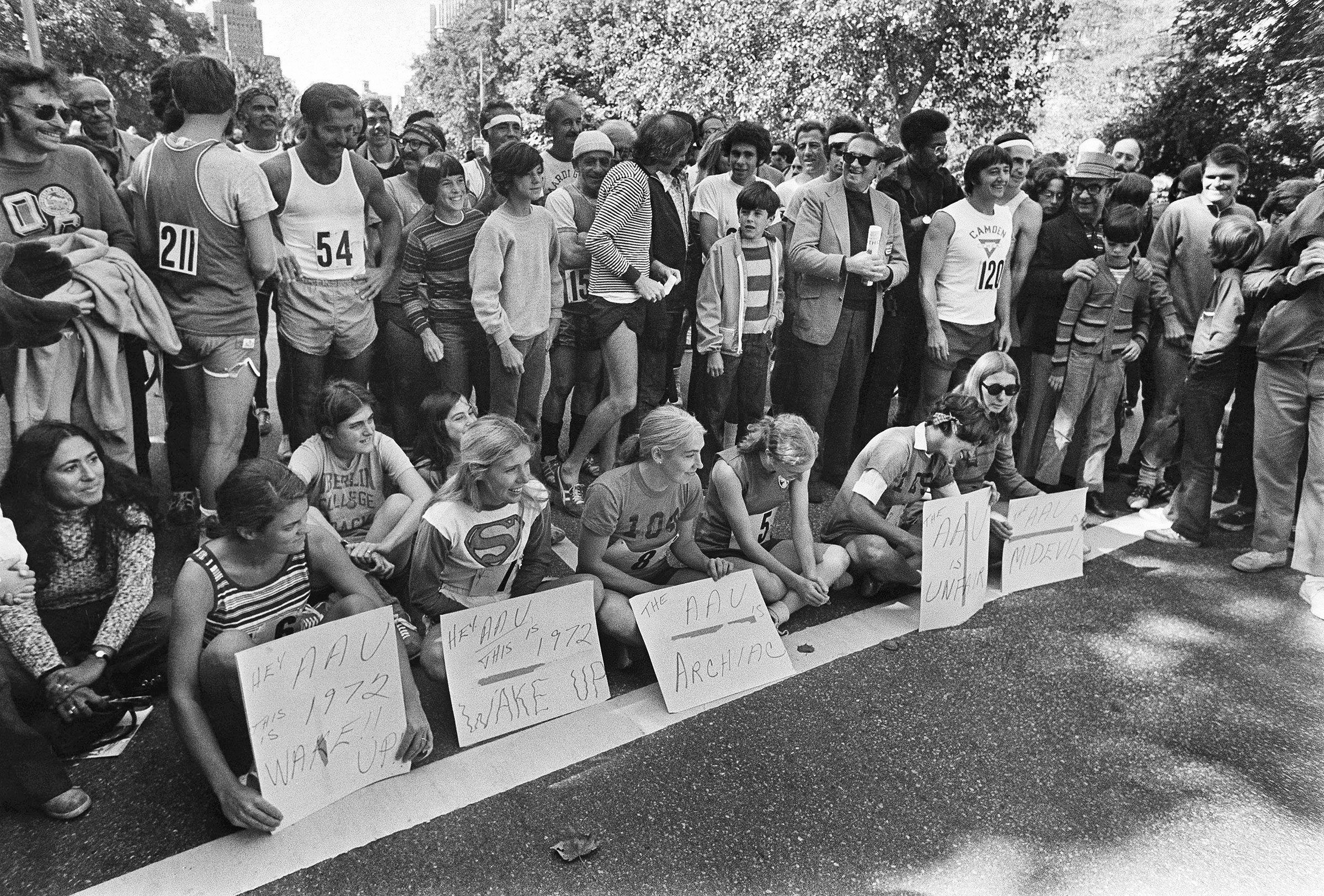

On a clear day—Sunday, Oct. 1—the gun went off to launch the New York City Marathon—but the 500 spectators stared not at the runners, but at six women who plopped down at the starting line.

Nicknamed the “Six Who Sat,” Lynn Blackstone, Pat Barrett, Liz Franceschini, Nina Kuscsik, Cathy Miller, and Jane Muhrcke, were protesting the governing body for marathons, the Amateur Athletic Union, to show the ridiculousness of its rule that women could take part in the marathon, but only if they ran a separate race—starting either 10 minutes before or 10 minutes after the men start.

“They sat for 10 minutes in protest against the Amateur Athletic Union, which had called for a separate‐but-equal race for women,” as the New York Times reported back then. “The A.A.U. does not sanction races in which men compete against women. But as soon as the 272 men were ready to go, the women stood and then began running with the men on the 26‐mile, 385‐yard course.”

As the above photo shows, the protesters held signs that said “Hey, AAU This is 1972 WAKE UP”, while other signs called the AAU “unfair” and “archaic” and “midevil.” The New York Times reported that one spectator shouted, “Men and women together!” In fact, it was the male New York Road Runners club president and NYC Marathon co-founder Fred Lebow who tipped off the New York Times that something would be happening at the marathon. Patrick Burns—who took famous photos of spontaneous celebrations in Times Square on V-J Day—snapped the image of the women at the starting line, featured above.

“They were very media savvy,” Kerin Hempel, current CEO of the non-profit New York Road Runners, which organizes the NYC Marathon, says. “Having the sit-in in New York, bringing media there, and also bringing signage, helps to really catapult the women’s running movement forward in a way that women just jumping into races on their own hadn’t moved the needle as much before that.”

Read more: How Title IX First Changed the World of Women’s Sports

The demonstration came at a time when notions of women’s roles in American society were expanding, including in the athletic arena. A few months earlier, President Richard Nixon signed Title IX into law, best known as the law that banned sex discrimination in schools and paved the way for more opportunities for women in school athletics. Running was already heading in that direction; just weeks before Title IX’s passage, New York Road Runners had started a women’s-only race.

The marathon organizers got the message; they dropped the separate start times. Two years later, a woman won the NYC marathon—Kathrine Switzer—seven years after she became the first woman to run the Boston marathon in 1967 when she registered under the male-sounding name K.V. Switzer. Women are now hard to miss in marathons, rising from 12% of the 10,477 finishers in the 1979 NYC marathon to 42% of the 53,640 finishers in 2019. In the 2021 NYC marathon, women made up 45% of the 25,020 finishers.

Read more: How Boston Helped Invent the Modern Marathon

In recent phone conversations, three of the “Six Who Sat” reflected on what was going through their heads when they participated in the demonstration and the meaning behind their bold action.

“In the ‘70s, the women’s movement was very strong and growing and very popular,” says Jane Muhrcke. While she’s never been a runner, usually just cheering on her husband, the then-28-year-old felt so outraged by the different treatment of male and female runners that she joined the sit-in and then ran about half a mile and ducked out.

Pat Barrett was 17 back then, and remembers participating in the sit-in to protest the AAU “using their authority to keep us at a certain level.” The experience was nerve-wracking, however; she just remembers the whole time thinking about how she was going to pace herself for the next 26 miles. But she recalls that the male runners were on the protesters’ side, laughing at the absurdity of different start times.

“They were very supportive,” Barrett recalls. “The men actually wanted women to be able to have that opportunity” to compete at the same level.

Lynn Blackstone, who was 32 when she participated in the sit-in, says, “I was simply in the right place at the right time to become part of history.” Female runners in 1972 encountered a lot of sexist remarks from men running past them, she says, while some men told women falsely that running would make their uteruses fall out . “There would only be comments on your legs, comments on how you look,” Blackstone says.

Participating in the protest kicked off a lifelong love of running for Blackstone, and she went on to complete the NYC Marathon three times. She ran through two pregnancies and still runs today, at the age of 82, with Central Park Track Club members who call themselves “The Medicare Group.”

Whether they’re runners or not, Blackstone says the sit-in’s lesson for women is the same: “Don’t limit women, and women should not limit themselves.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com