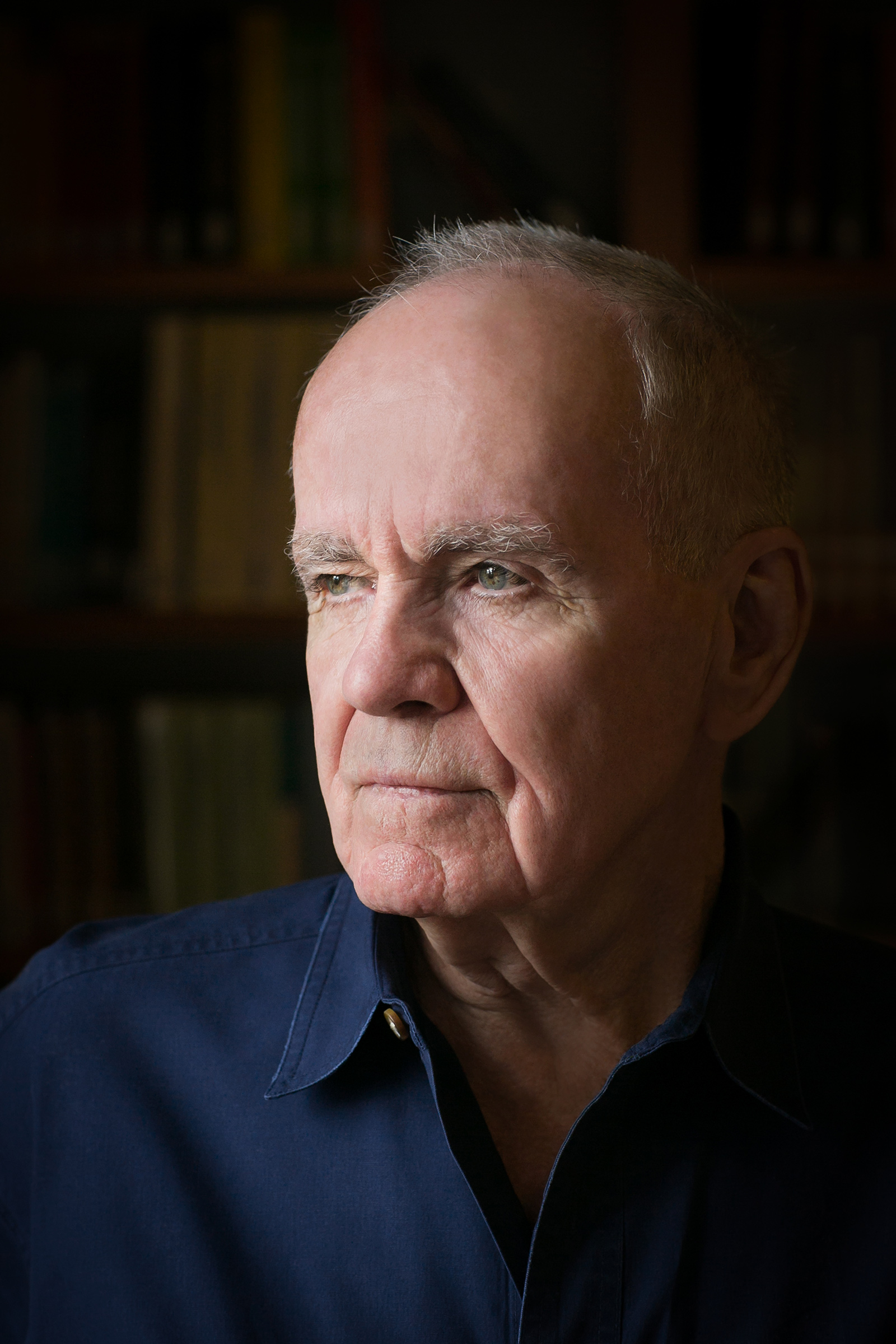

Cormac McCarthy, the now 89-year-old winner of both a National Book Award and a Pulitzer Prize, whose work is compared, not infrequently, to Moby Dick and the Bible, has spent more than two decades as a senior fellow at the Santa Fe Institute think tank. The list of operating principles for the institute (which he wrote), reads in part: “If you know more than anybody else about a subject, we want to talk to you.”

With his two staggering new novels, the companions The Passenger and Stella Maris, it’s clear that McCarthy—best known for delivering stark, gory tales of morality and depravity—has been inspired by his time at the think tank talking to the world’s greatest mathematicians and physicists. His first works of fiction to be published in 16 years begin in familiar territory but push his ambitions to the very boundaries of human understanding, where math and science are still just theory.

In The Passenger, the first of the two books, Bobby Western is a 37-year-old deep-sea salvage diver operating mostly in the Gulf of Mexico—dangerous but lucrative work that’s not unlike exploring a foreign planet. One night Bobby and his dive partner receive a strange assignment: a small passenger jet has crashed in the water off the coast of Pass Christian, Miss., and they must dive 40 ft. under the surface to assess the situation. When the pair finds the wreck, they encounter nine bodies sitting buckled in their seats, “their hair floating. Their mouths open, their eyes devoid of speculation.” In addition to the oddly intact fuselage, other things are out of place. The pilot’s flight bag is gone. The plane’s black box has been neatly removed from the instrumentation panel. And a 10th passenger, listed on the manifest, is missing completely. Bobby’s partner is spooked. “You think there’s already been someone down there, don’t you?” he asks.

Soon Bobby is beset by suited men—agents of an unnamed government entity—flipping their badges at him and asking him questions. Then his friend goes down on a dive and doesn’t come back up.

Read More: The 33 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2022

In many ways, Bobby resembles Llewelyn Moss, the protagonist of McCarthy’s 2005 novel No Country for Old Men: laconic, capable if a bit hapless, and the subject of dangerous intrigues outside of his scope. The difference is that Bobby has book smarts as well. His father was a scientist on the Manhattan Project who rubbed shoulders with Oppenheimer et al. while they perfected, as Bobby’s university friend Long John puts it, “the design and fabrication of enormous bombs for the purpose of incinerating whole cities full of innocent people as they slept in their beds.”

Bobby gave up physics to travel around Europe as a midtier race-car driver before starting his career in diving. Both pursuits appeal because they offer him momentary relief from not only his own intelligence but also his grief. Long John diagnoses the final integral component of Bobby’s character: “He is in love with his sister. But of course it gets worse. He’s in love with his sister and she’s dead.”

McCarthy alternates chapters of The Passenger between the mystery at Bobby’s hands and conversations that his younger sister Alicia—the most brilliant in a family of prodigies, who died by suicide nearly 10 years prior—has with figures of her schizophrenic hallucinations. Their ringleader, whom she has come to call “the Thalidomide Kid,” is a bald, scarred imp about 3 ft. tall, with “flippers” instead of arms. (“He looked like he’d been brought into the world with icetongs.”) The Kid taunts Alicia in strange idioms in between discursions on time, language, and perception. From one of his linguistically withering rants: “Well mysteries just abound don’t they? Before we mire up too deep in the accusatory voice it might be well to remind ourselves that you can’t misrepresent what has yet to occur.” Fans of McCarthy’s work will agree that this novel’s villain is a far sight more loquacious than No Country for Old Men’s Anton Chigurh. (“Call it.”)

Narratively speaking, the book is more interested in expanding the scope of its own mystery than in solving it. The Bobby sections depict him avoiding the plot entirely—he mostly has lunch with friends and converses with them about his past, physics, or philosophy. Don’t come here for a thriller about a plane crash, but the pages do turn with remarkable ease. From the initial mystery of a missing person, the novel explodes outward like an atomic chain reaction to the very face of God, at the intersection of mathematics and faith.

Is this sounding like a lot? It is. The Passenger also happens to be something of a masterpiece, an unsolvable equation left up on the blackboard for the bold to puzzle over. Readers have been waiting years for this novel, which McCarthy has teased from time to time, dating back to before The Road, which he published in 2006. It is his most ambitious work, or perhaps a better word would be weirdest. But it’s held together with wit and chuckle-out-loud humor, which can be sparse in his other novels (see the apocalyptic violence of Blood Meridian). And it’s genuinely fun to read throughout—although readers who come to this book because they enjoyed an airport paper-back edition of The Road while on a short flight might be left wide-eyed and blinking.

Stella Maris, the slimmer companion, to be published in December, is just over 200 pages’ worth of Passenger’s late sister Alicia’s dialogues with her psychiatrist after she has institutionalized herself toward the end of her life, suffering under the power of her own intellect. It offers a few more clues, but mostly deepens the various mysteries on offer in the first novel. “Mathematics,” she tells her doctor, who struggles to keep up, “is ultimately a faith-based initiative.”

In all of his books, McCarthy is a gearhead, a man obsessed with hardware and the nuts and bolts of things. There are no planes and cars in The Passenger, only “JetStars” and “1968 Dodge Chargers with 426 Hemi engines.” A person doesn’t glance at their watch; they glance at their white gold Patek Philippe Calatrava. There are whole sections that could read almost as instructional home repair or auto maintenance: “The teeth had begun to strip off of the cluster gear until the box seized up and then the rear U-joint came uncoupled and the drive shaft went clanking off across the concourse … ” It’s been said that when McCarthy visited the set of the movie adaptation of All the Pretty Horses, he spent most of his time with the props master talking about guns.

So it makes sense that at this stage in his career, the author would push in his chips and attempt to understand the mechanical clockwork of reality itself. Like Bach’s concertos, these triumphant novels depart the realm of art and encroach upon science, aimed at some Platonic point beyond our reckoning where all spheres converge.

It’s a rare thing to see a writer employ the tools of fiction in order to make a genuine contribution to what we know, and what we can know, about material existence. Put differently, the ideal audience for these books are Fields Medal recipients, but they’re still a privilege and a hoot for the rest of us to read. And if we can’t understand everything McCarthy is writing about, one suspects that he just might.

Mancusi is the author of the novel A Philosophy of Ruin.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com