“I met with three different Jewish therapists. I chose you.” Sam Fortner, an unusually introspective serial killer played by Domhnall Gleeson, says many chilling things to Steve Carell’s character, Alan Strauss, the therapist he has kidnapped, in the premiere of FX’s The Patient (which will stream exclusively on Hulu beginning Aug. 30). Yet that’s the utterance that haunted me for the duration of the miniseries’ 10 episodes—surely in part because I am Jewish, but to an even greater extent because, as scripted, Sam’s comment is so conspicuously free of any explanation or context. You’ve heard of Chekhov’s gun; this is Chekhov’s stereotype.

It fires, so to speak, more than once, in so many directions it could make your head spin. Creators Joel Fields and Joe Weisberg, who collaborated on FX’s modern-classic spy drama The Americans, understand how to subvert expectations while exploring characters’ psychology and building suspense. Judaism becomes a theme; clearly, there are historical precedents for the image of a Jewish man, held captive for reasons related to his religious identity, waiting to be liberated or killed. The metaphor of Alan’s faith reverberates through each episode of this ambitious, flawed, masterfully acted show in ways both ham-fisted and profound.

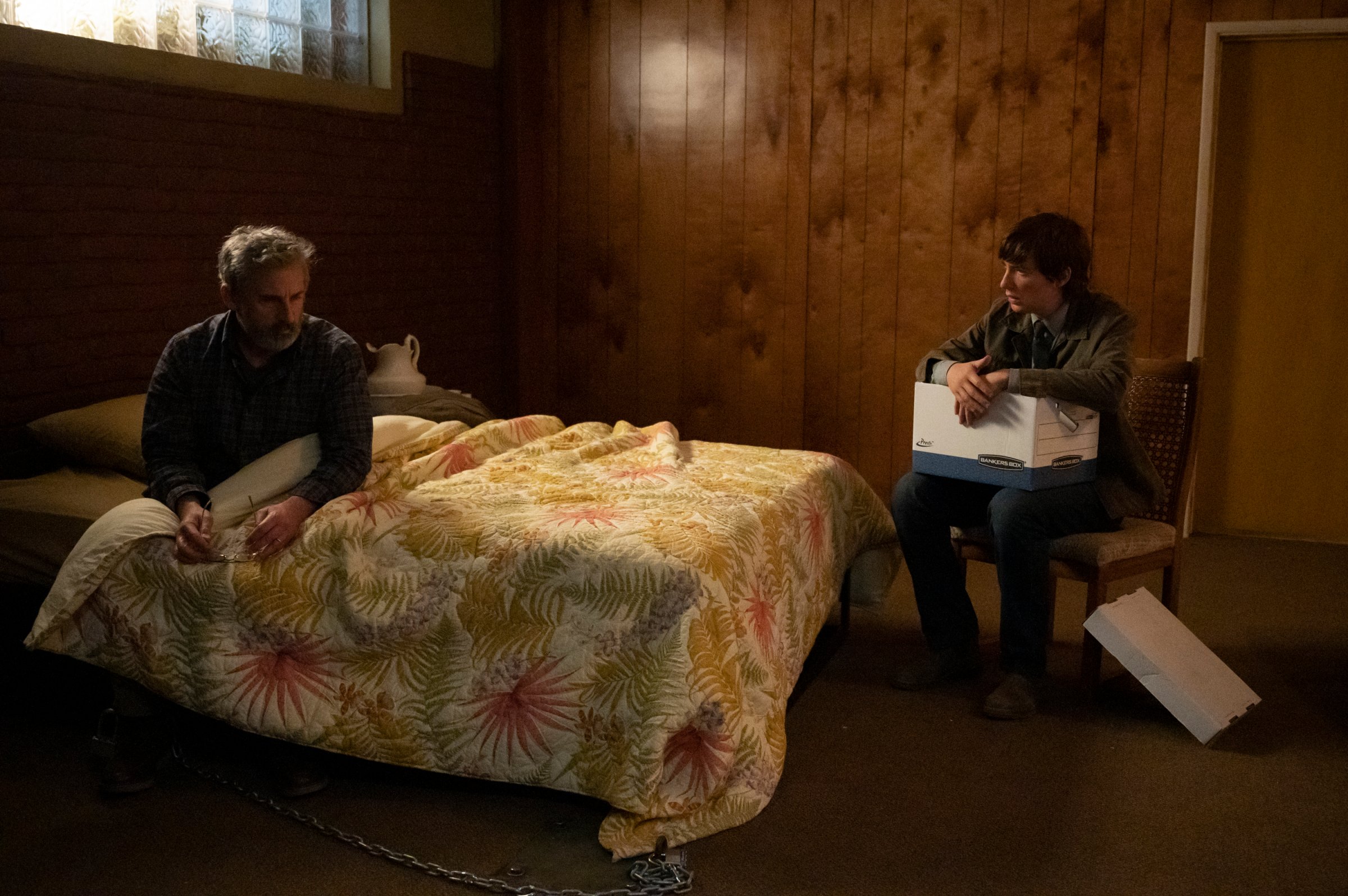

The Patient unfolds, in large part, as a series of therapy sessions that Sam forces Alan to lead while chained by his ankle to the floor of the wood-paneled basement of Sam’s childhood home. Initial appointments in Alan’s office, during which Sam used a fake name and concealed the fact that he’d already committed multiple murders, convinced the so-called patient that he would need to create a safer environment to level with his therapist and seek help to stop killing. This combination of brutality and conscience makes Sam an anomaly among the many affectless, unrepentant psychos who populate crime dramas; Gleeson plays him as a wounded, easily enraged, man-sized child who wants to do the right thing but can’t control his violent impulses.

Alan is, in many ways, Sam’s opposite. Soft and gray-bearded, in contrast to his wiry, younger, clean-shaven captor, he does have one major advantage: his decades of experience as a therapist. Skilled as he is at coaxing reflection and change out of patients, Alan must determine how best to calibrate his behavior in service of escaping this basement alive—preferably while keeping Sam from killing anyone else. But will the techniques he’s refined over years of treating garden-variety neuroses actually work on a person who’s prone to murdering any stranger who slights him? And even if he does succeed in curing Sam’s homicidal tantrums, how can Alan convince Sam to set him free, now that he knows so many damning secrets? Carell, in the best dramatic performance of his career, silently registers the weight of these anxieties, as Alan struggles to maintain his dignity and self-discipline in a predicament that would terrify anyone.

As in most patient-therapist relationships, family becomes a theme. Early on, in a development that flirts with unbelievability, we meet Sam’s mother (Linda Emond, recently excellent in Lodge 49), a textbook enabler who is determined to protect her son at all costs. It seems likely that her dangerous protectiveness is compensating for her failure to save him from an abusive father. “My dad beat the sh-t out of me,” is all Sam will say to Alan about his childhood, at first.

More nuanced is the show’s depiction of Alan’s family, whose quieter troubles he has plenty of time to reflect on while Sam is at his job as a restaurant health inspector. (An obsessive foodie with an adventurous palate, Sam thoughtfully picks up dinners for Alan from his favorite takeout joints.) As she battled the cancer that would eventually kill her, Alan’s wife Beth (Laura Niemi), a cantor at the couple’s Reform synagogue, had also been feuding with their adult son Ezra (Andrew Leeds), who married into an Orthodox sect and used his strict observance of Jewish law to put up walls between his kids and their grandparents. But Alan is so fixated on the faith-based conflict between Beth and Ezra that he can’t see his own role in it. In one of many imagined sessions with his own therapist (an authoritative David Alan Grier) he envisions telling his son: “Ezra, you broke up our family.” On some level, he blames Ezra for Beth’s death.

Read More: Three Minutes: A Lengthening Is a Quietly Moving Portrait of Life Before the Holocaust

Alan’s imagination also conjures up concentration camps. There he is in a bunkhouse cramped with emaciated prisoners; there he is in the gas chamber, as exhaust fumes seep out from the ceiling. The show lingers on Jewish mourning rituals and highlights the tragic yet fruitful relationship between psychotherapy and Jewish suffering, alluding to the work of Auschwitz survivor Viktor Frankl. And it demonstrates how the Holocaust shapes the way Alan thinks about his imprisonment—and how hard he dares to fight back. But it fails to draw a meaningful connection between this symbolism and the role faith plays in the life of Alan’s family. Judaism becomes a pervasive but underdetermined motif, a refrain more than a theme. At one point in a flashback, he frowns over an anti-Zionist flyer that replaces the Star of David on an Israeli flag with a swastika; Fields and Weisberg raise this loaded issue without returning to it.

For all of its engagement with religious identity—and despite the many questionable assumptions it makes about the nature-to-nurture ratio that might yield a serial killer—The Patient is most effective as a simpler sort of psychological thriller. Sam, a son poisoned by his father’s abuse, truly likes and appreciates Alan but can’t see a safe way to let him live. Alan, a father who is only beginning to acknowledge his resentment towards his son, needs to use his intelligence and expertise not primarily to heal Sam but to escape his clutches. It’s a fascinating relationship, expertly developed through short, suspenseful episodes, thoughtful dialogue, and a pair of note-perfect performances. But the rest, as the Strausses might say, is mishegas.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com