On the first day of one of the first AP African American Studies classes ever taught, Marlon Williams-Clark rattled off a list of Black luminaries to see how many his students had heard of.

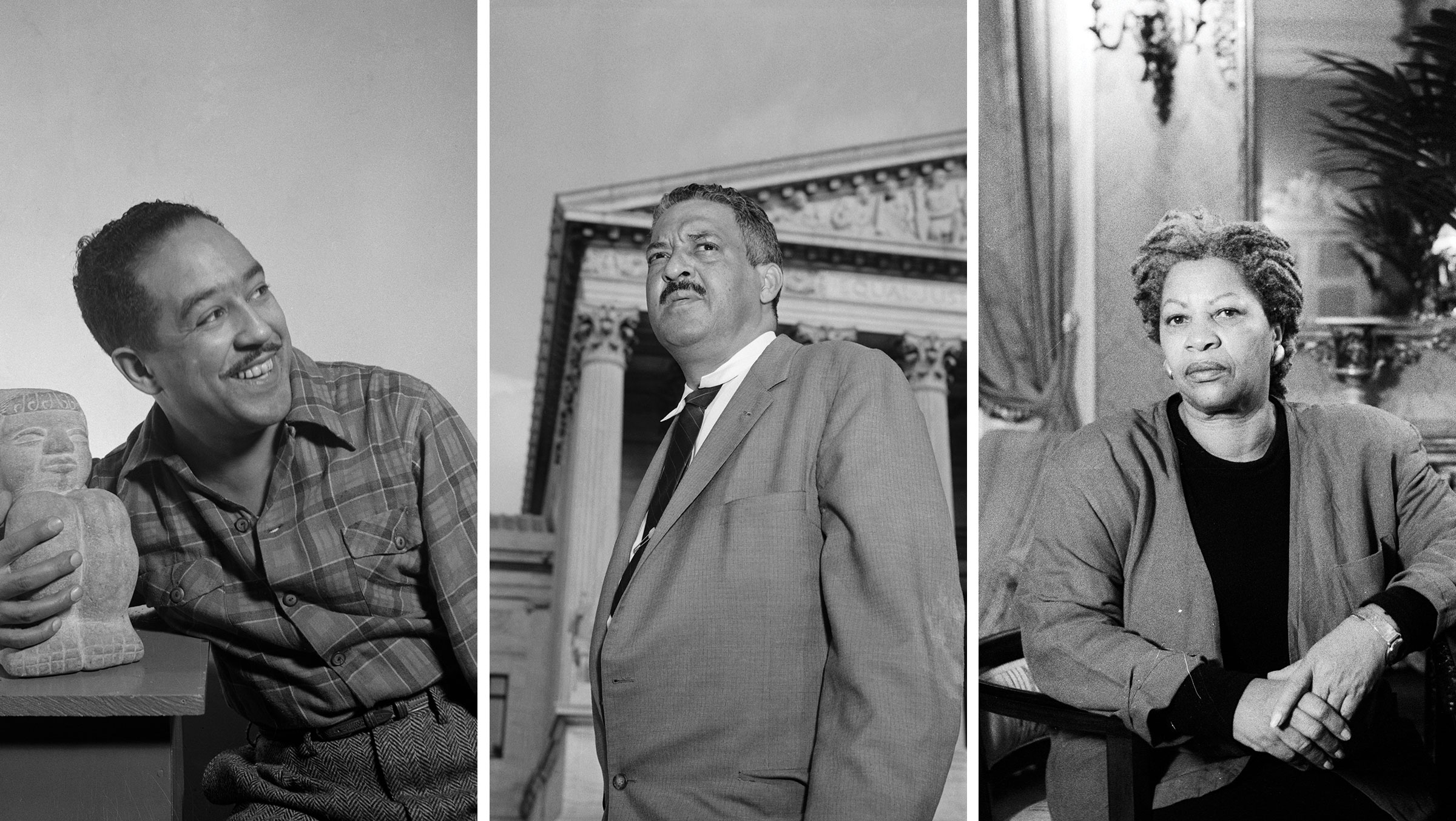

Only one of the high-schoolers in the majority-Black Tallahassee, Fla., class, which kicked off this month, recognized Thurgood Marshall, the first Black U.S. Supreme Court justice. And he got no reaction to Pulitzer Prize winner and Nobel laureate Toni Morrison. Everyone recognized Maya Angelou, but most hadn’t heard of Langston Hughes or Zora Neale Hurston.

Williams-Clark is teaching at one of 60 schools nationwide piloting AP African American Studies this year. The course will be the College Board’s 40th Advanced Placement course, and the first new AP course since 2014. Next year, students will officially be able to take the class to earn college credit at about 35 colleges, from Virginia Tech to Tuskegee University.

Yet the pilot program arrives at a time when lessons on the Black American and African diaspora experience are at the center of a nationwide debate. Teachers are being accused of teaching “critical race theory,” a decades-old academic framework that in fact is rarely taught below the graduate level. Among scholars, CRT is a way to look at how legal systems and other institutions perpetuate racism and exclusion. But in the popular imagination of the past several years, it has become a byword for anything to do with teaching the history of racism in America.

Read more: Anti-‘Critical Race Theory’ Laws Are Working

At least 19 states have passed laws or rules aimed at regulating how race is talked about in the classroom. State lawmakers have been pushing to ban the teaching of the New York Times’ 1619 Project, a multimedia series that examines U.S. history through the lens of the Black experience, beginning in 1619 when the first enslaved Africans were sent to Virginia. And the American Library Association has been seeing an unprecedented amount of attempts to ban books in school libraries, mostly about topics in Black history by Black and minority authors, like Toni Morrison.

In fact, Williams-Clark, who teaches African American History at the Florida State University Schools, guesses those bans may have something to do with Morrison’s lack of name recognition in his classroom. He and his students, even as they embark on the College Board’s curriculum, find themselves at the crossroads of a culture war. “I live in Florida,” he says, “so I had to let them know that I have to be careful about how I might phrase some things or some of the topics that we may learn about.”

In 2021, the Florida Education Board approved a rule banning the teaching of critical race theory and the 1619 Project in schools. In April, the legislature passed the Stop WOKE Act, which aims to regulate how schools talk about race.

More from TIME

“Nothing is more dramatic than having the College Board launch an AP course in a field—that signifies ultimate acceptance and ultimate academic legitimacy,” says Henry Louis Gates Jr., one of America’s foremost experts on African-American history, who helped develop the AP African American Studies curriculum. “AP African American Studies is not CRT. It’s not the 1619 Project. It is a mainstream, rigorously vetted, academic approach to a vibrant field of study, one half a century old in the American academy, and much older, of course, in historically Black colleges and universities.”

What’s in the AP African American Studies course

The AP African American Studies course is interdisciplinary—not only diving into the history of the African continent, but also covering uplifting topics such as African American music and the significance of the Marvel Black Panther movie. It looks back at more than 400 years of contributions to the U.S. by people of African descent, going as far back as 1513, when Juan Garrido became the first known African in North America while on a Spanish expedition of what’s now Florida.

AP courses are high school classes designed to get students ready for college-level work, and are typically the most rigorous courses offered in many schools. The College Board outlines the material students have to know for the final exams, which are developed and graded by college faculty and AP teachers.

To succeed on the pilot AP African American Studies test, students will have to understand the concept of intersectionality, a way of looking at discrimination through overlapping racial and gender identities, and know that while it was written about by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw—a leading thinker on critical race theory—it was also talked about by 19th century thinkers like Maria Stewart, a teacher who argued that racism and sexism had to be studied together.

While the Reconstruction era after the Civil War is often skimmed over in high school U.S. history classes, AP African American Studies delves into progress made at that time, as well as how the roots of today’s mass incarceration system can be traced back to that era.

There are in-depth lessons on the speeches of Malcolm X and the Black Panther Party’s free breakfast and medical programs, often seen as taboo topics to cover in class because critics historically smeared the group as violent and communist.

In light of the newest federal holiday, Juneteenth, the curriculum features a primer on June 19, 1865, when the enslaved in Galveston, Texas, learned that they were free.

And while students have the option to do research on the history of the reparations movement and Black Lives Matter activism, they won’t be required to know these topics for the AP exam.

Growing interest in African-American history

While many of the issues surrounding how African-American history is taught are at the center of the ongoing culture war, this course is more than a decade in the making. The College Board, a nonprofit that administers college-entrance assessments like the SAT, says high schools had frequently been asking for an AP African American Studies class, but when it asked colleges and universities a decade ago if they would accept college credit for such a class, the answer was no. When College Board leaders posed the question to universities again recently, they got a resounding yes, says Trevor Packer, head of the College Board’s AP Program.

“The events surrounding George Floyd and the increased awareness and attention paid towards issues of inequity and unfairness and brutality directed towards African Americans caused me to wonder, ‘Would colleges be more receptive to an AP course in this discipline than they were 10 years ago?’” says Packer.

The College Board also hopes AP African American Studies will draw students who are usually underrepresented in AP Classes. A 2021 report by the Center for American Progress found that Black students are less likely to enroll in AP classes than their white and Asian peers and are more likely to attend schools without AP classes.

“Many of my students report back to me while they’re in college, and they say it would have been so good to have this particular course,” says Nelva Q. Williamson, who is teaching the course in Houston, and says she plans to include classroom discussion of local examples of redlining.

Part of the reason the AP African American Studies course is a revelation for many teachers is that there is no standardized K-12 curriculum for the subject nationally. As Sharon Courtney, a teacher in Peekskill, N.Y., who is participating in the pilot, put it, “Everyone’s doing their own thing in different parts of the country [and] I’m really happy about the College Board’s ability to standardize the curriculum and put it out there for everyone, at a time when the country needed an organized approach to combat the firestorm of opposition to critical race theory and teaching anything that revolves around African Americans in this country.”

In fact, while it may not be on the exam, that’s one topic that teachers say is sure to come up in class: Students are wise to the controversy and are ready to talk about it.

In Tallahassee this month, Williams-Clark was going over concepts from the course on how Black-studies programs launched in colleges and universities in the mid-20th century. His students started trying to relate that history to the backlash surrounding the teaching of ideas from those programs in 2022. “I was just thinking, man, don’t get me fired!” he jokes.

But he sat back, he says, and let the students talk it out.

“I just feel like we’re in a dangerous moment, but we’ve got to keep going,” he says. “We’ve got to keep pushing. We’ve got to keep fighting. We’ve got to keep teaching.”

Clarification, Sept. 1

The original version of this story stated the course offers in-depth units on Malcolm X and the Black Panther Party. It will offer lessons on these topics, not units.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com