When 10 Black shoppers were killed at a Buffalo, N.Y., supermarket, allegedly by a white 18-year-old with a history of racist writings, history teacher Mary McIntosh didn’t know how to talk about it with her high schoolers in Memphis, Tenn.

Tennessee is one of 19 states with laws or rules designed to regulate how racism and issues of race are discussed in the classroom. The Buffalo shooting was a stark example of a national news event that McIntosh says she struggled to address with students, even while teaching to a predominantly Black and brown student body.

While she usually teaches civil rights lawyer Bryan Stevenson’s memoir Just Mercy, she shelved it this past school year because she was afraid the parts about the historical legacy of racism in the criminal justice system would run afoul of the “prohibited concepts” outlined in the law. And while in the past she’s used the site Facing History and Ourselves, which offers historian-approved curriculum resources, this year she hesitated to draw from some of its lessons tying contemporary issues to the past.

“The Tennessee law does indeed have a big impact on how I can plan to teach with honesty and integrity,” she says.

The law, passed in May 2021, says it permits “impartial” discussions of the “controversial aspects of history” and “the historical oppression of a particular group of people.” But, teachers may not teach “resentment” of “a class of people” or that “an individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, is inherently privileged, racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or subconsciously.” Students, parents, or employees of a school can file complaints about teachers who violate the law. Schools found to have violated the law stand to lose 2% of their state funds or $1 million, whichever is less, for each violation.

McIntosh believes that her fear and reticence in teaching about racism are the point of the law. “All someone has to do to win is to just chill people,” she says.

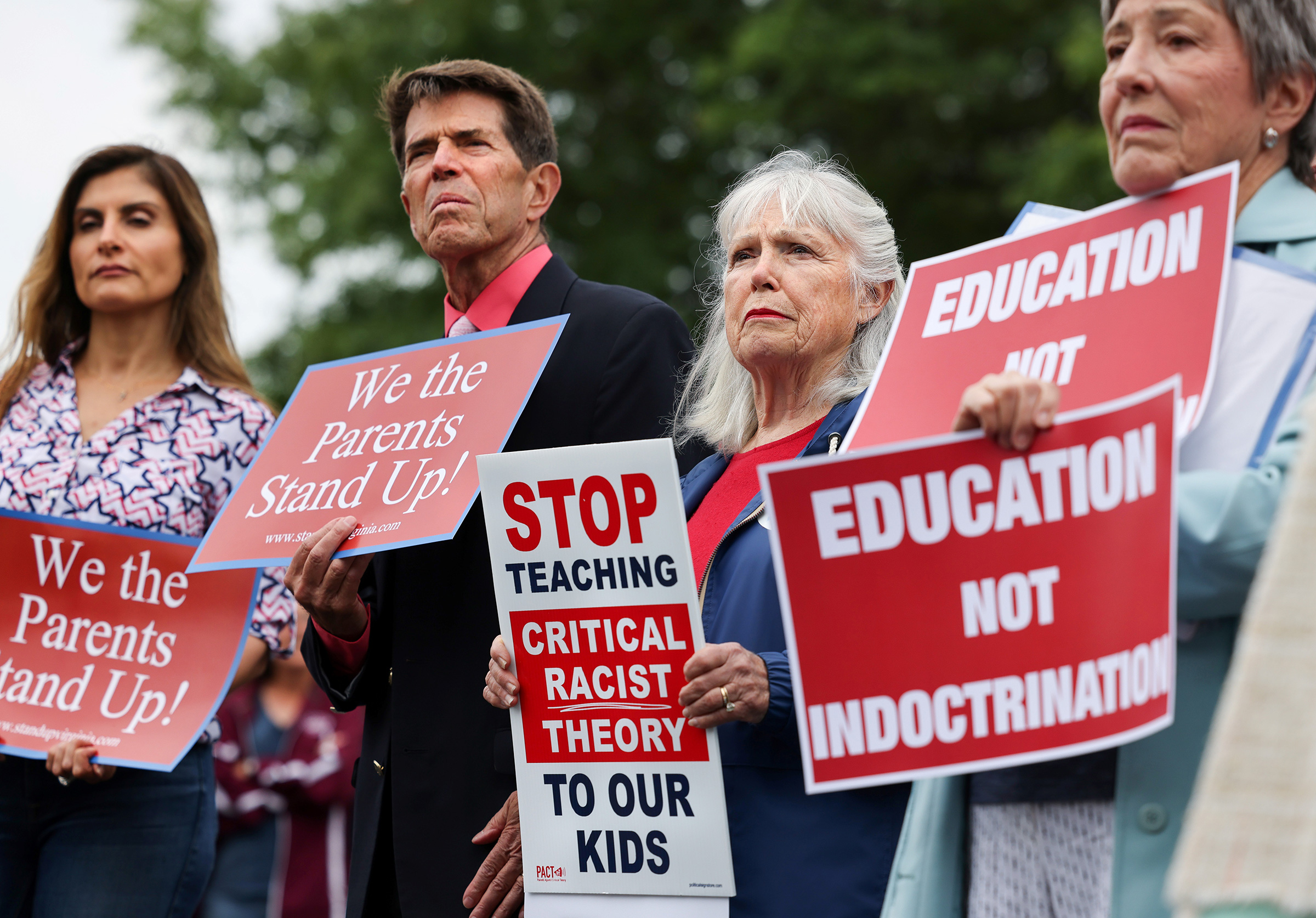

The controversy over how issues of race, racism, and diversity are taught in schools reached a boiling point around the Fourth of July in 2021. Much of the attention from conservative activists focused on critical race theory (CRT), a decades-old academic framework that scholars use to interrogate how legal systems, as well as other elements of society, perpetuate racism and exclusion. And at least 19 states have so-called “anti-critical race theory” laws or regulations—despite the fact that CRT is rarely taught below the graduate university level. Even more school boards enacted policies or changed curricula in an effort to restrict how teachers talk to their students about race and diversity.

At the end of a school year during which teachers in states across the country saw how these laws played out, many educators say that there has been a chilling effect on teaching lessons related to race and racism, and that they are struggling to provide historical context for current events. TIME spoke to more than a dozen teachers for this article; and while some said they would not shy away from teaching hard truths about the enduring legacy of racism in America, others worried that speaking out on controversial issues could cost them their jobs. The effect of these laws was even felt in school districts and in states that don’t have anti-CRT laws; educators say they are acutely conscious of school assignments or discussions that could rile up parents or conservative activists.

The ‘anti-critical race theory’ backlash

For many Republicans, the issue boils down to what they see as teachers overreaching in the classroom and allowing liberal biases to influence how they instruct students. As Tennessee state Rep. John Ragan, a co-sponsor of his state’s bill, says via email, “In Critical Race Theory there is no acknowledgment that all men are created equal or have divinely bestowed individual rights. We aren’t going to teach hate in Tennessee. We aren’t going to teach our children to demonize each other.” (Critical Race Theory scholars don’t see the theory this way; they believe it offers a method for thinking about the impact of hate and moving beyond it.)

Many conservative politicians hope the issue—a variety of parental concerns about education, which often get lumped under the umbrella of Critical Race Theory—will drive people to the polls in the November midterm elections. They got some encouragement last fall when Glenn Youngkin made education a core part of his winning platform to become Virginia’s governor. An April 2022 Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll showed Americans split on how much more involved parents need to be in curriculum decisions. About half of Americans say parents have “too little influence on curriculum.” Twenty percent said they have “too much” and 27% said “it’s about right.”

Read more: The Education of Glenn Youngkin

In states from Colorado to Iowa, some bills required teachers to post their syllabi and all of their class readings online—opening them to challenges from parents, or activists who might agree with their decisions. One Florida bill even proposed installing video cameras in classrooms.

How these anti-CRT laws and rules are enforced is still playing out, but so far it’s been “very haphazard,” says Jeremy Young, who has been tracking these laws at PEN America, a free-speech advocacy group. “What we’re seeing is censorship from school districts, lectures being canceled, classes being scrutinized in ways that they weren’t before, an epidemic of self-censorship among teachers, and teachers not being able to answer students’ questions,” he says. A UCLA study found school districts that are quickly diversifying tend to get more queries from parents about how they’re teaching race and sexuality than school districts that have seen minimal change in the white student population.

In Texas, which has an anti-CRT law, educators report being confused about what is and isn’t off-limit, says Morgan Craven, an education policy advocate at IDRA, a group that’s been advocating against classroom censorship bills. “I’ve heard of teachers saying things like ‘Well I guess this means we can’t celebrate Black History Month anymore,’” Craven says.

Read more: How Black Lives Matter Is Changing What Students Learn During Black History Month

Since Florida passed the Stop WOKE Act, which aims to regulate how schools talk about race, in April, Matthew Bunch, who teaches advanced placement U.S. government in Miami Dade County, says he’s “dreading” teaching Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” next year because it addresses citizens’ right to challenge the government if they feel like their rights are being violated. “I don’t know how, without trampling on one of those landmines, we can actually talk about the document and what it means and what it influences.”

Even in states that don’t have laws regulating the teaching of the history of racism, school districts are on the lookout for anything that could be seen as controversial and that parents might complain about. Akron, Ohio, teacher Hannah Couch says that during Black History Month, fellow staffers thought hallway posters that she helped students design of Black gay and trans couples and the Black Lives Matter flag were “too political.”

Teachers in states with solidly Democratic legislatures are not immune from the pressures from “anti-critical race theory” parents and school board members. In Elmhurst, Ill., parents formed the website Elmhurst Parents for Integrity in Curriculum, singling out local history teacher Lindsey DiTomasso for conducting a role play from the Zinn Education Project (the educational arm of Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States and a site with lessons on history topics) that re-imagines the Constitutional Convention with groups excluded from the original meeting, like women and enslaved Black Americans. The site claimed that she “encouraged students to gang up on and bully property owners and bankers,” and the hyperlocal news outlet Patch ran articles quoting residents who accused her of bias.

Read more: Schools are failing to teach Reconstruction

DiTomasso says she had never received criticism for the lesson before in 13 years of teaching it. “We’ve been doing this activity for years and years, but this year, it was considered questionable,” says DiTomasso. The pushback has made her think twice at times while lesson planning, but ultimately, she hasn’t made major changes to her curriculum. “I would be lying if I told you every day I leave school, I don’t walk out to my car and wonder if someone’s going to be out there,” she says.

The controversy has, inevitably, begun to touch students in the classroom, as well. In Memphis, McIntosh has had to field questions about Tennessee’s anti-critical race theory law from her students. “There was a discussion [about it] in one of my classes, and people kind of rolled their eyes, and one young man said, ‘Oh, people just don’t want to feel bad, talking about white people.”

Pushing back against the backlash

There have been some wins in the movement against anti-CRT efforts. In Indiana, a coalition of organizations mobilized to defeat two anti-critical race theory bills after a Republican state senator urged teachers to be impartial on “isms,” and a history teacher went viral for saying he refuses to be impartial when teaching Nazism. In New Hampshire, a group called Granite State Progress boasted wins in all 34 of the school board races where it supported candidates who pledged to resist pressure to restrict the teaching of the history of racism.

Yet the anti-CRT proponents have still been louder than the resistance movement. Justin Hansford, a law professor at Howard University overseeing a hotline counseling teachers who want to know their legal rights in curriculum challenges over the last year, says: “I was looking for something similar to what happened after George Floyd was killed. But it has not been at that level. There definitely have been attempts to [protest], but it hasn’t been as widespread as I hoped.” Instead of waiting for teachers to call, the hotline has started reaching out to teachers directly because “a lot of them are very scared,” he says. “We have learned the fear is so great, many teachers are self censoring without putting up a fight, are afraid to speak out, or will only do so anonymously.”

In spite of this climate of fear, some teachers have managed to find teachable moments in the CRT controversy.

Another high school history teacher in the Memphis area, Daniel Warner, says the law has made educators second-guess themselves. “A lot of the trainings for U.S. history teachers in my district devolved into fears about, ‘Will I lose my job if I teach Jim Crow? Will I lose my job if I teach some of the basics of American history?’”

But Warner has gotten creative: He used Tennessee’s anti-CRT law to teach his students about the limits of freedom of expression during the Red Scare, the efforts to round up communists during the Cold War in the aftermath of World War II. He pointed out that a line prohibiting teachers from promoting the violent overthrow of the U.S. government is also in the Smith Act of 1940, which was used to put communists on trial. Teaching such a lesson, he says, is “definitely flipping the purpose of the law. But they didn’t say you couldn’t teach the law.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com