The May 25 death of George Floyd, 46, marks one more chapter in a long history for America — and for Minneapolis, which has been the site of protests in the days following Floyd’s death.

After Floyd, who was black, died in police custody, bystander video revealed that a white police officer knelt on his neck at a Minneapolis intersection. The video did not match initial police-department statements about what happened, and resulted in the firing of four police officers involved in the arrest. That the episode happened against the backdrop of a global pandemic has only heightened longstanding racial tensions. Not only is the virus disproportionately affecting African Americans, but the policed enforcement of social distancing in cities nationwide has also disproportionately affected African Americans.

Floyd’s death also “falls within a larger pattern” of clashes between police officers and residents in black communities that “goes way back to the period of Reconstruction, when a lot of police departments were created to surveil black communities and control and corral large black populations,” says Keith A. Mayes, a professor of African American & African Studies at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities.

But while the problem is national, Minneapolis has its own particular history with the issue. Several such encounters there helped fuel the Black Lives Matter movement. In 2019, Minneapolis was ranked the fourth worst metro area in the United States for black Americans, and the city is highly segregated. Accusations of police racism have also been a consistent issue for the city.

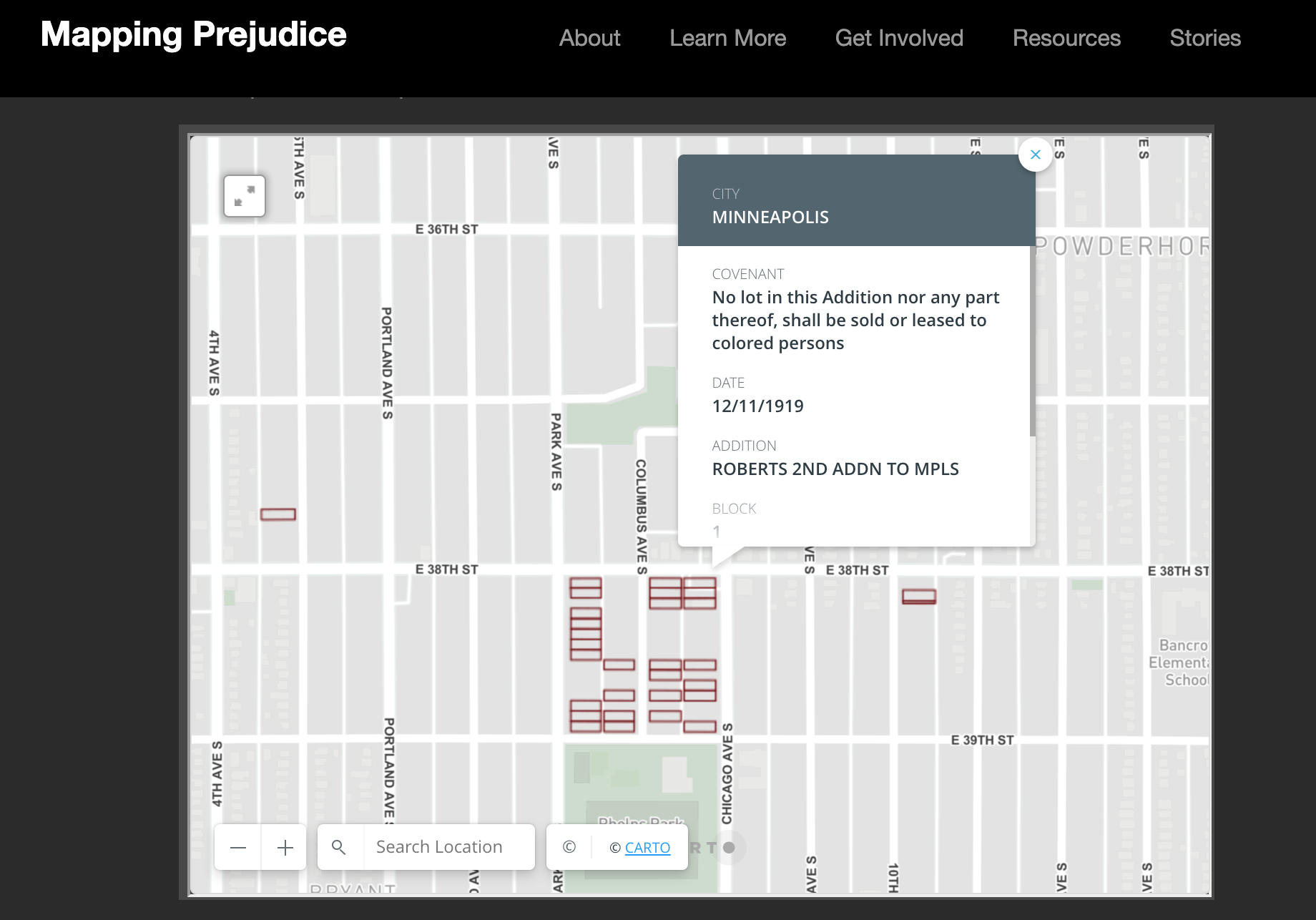

Understanding how things got so tense in Minneapolis requires understanding the history of the city’s racial geography, says Kirsten Delegard, a historian and director of Mapping Prejudice, a University of Minnesota project that has plotted the locations of racial covenants, legal clauses inserted into property deeds that reserved that land for the exclusive use by white people.

“Minneapolis wasn’t particularly segregated when racial covenants were first introduced in 1910; they were preemptively put into place before black people lived in Minneapolis in large numbers,” Delegard says. “You have 2,700 African Americans living in the city in 1910 and [then] 30,000 racial covenants blanketing the city to make sure all this land could never be occupied by people who aren’t white. After they had been in place for 30 years, the city became highly segregated and people who weren’t white were sorted into just a handful of very, very small neighborhoods.”

Those small neighborhoods include one near the intersection of 38th Street and Chicago Avenue in Minneapolis, where the officer knelt on Floyd and where subsequent demonstrations have taken place. The nearby area has historically been known as a hub for black middle-class life and working-class communities. Just west is the neighborhood’s commercial center, the Old South Side. It’s been home to African-American journalists, doctors and lawyers, as well as NAACP presidents, important black churches and some of Prince’s old stomping grounds.

“Like every black neighborhood in the country, it’s also been subject to over-policing and very different kinds of police practices than the predominantly white neighborhood a couple of blocks away,” she says. “When you get to the edges of those neighborhoods, there tends to be more literal policing and more contention over who can be in public space and what people are doing.”

The very intersection where the violent arrest took place is one such edge. At that corner, properties were governed by racial covenants. Delegard’s research shows these covenants were often put in place on the borders of black neighborhoods, in an effort to contain the population.

“Even though 38th and Chicago right now is not seen as overtly white space, what these covenants show is that this intersection has always been a point of contention. ‘Whose space is this? Who gets to be here? Who doesn’t get to be here? And who’s going to enforce that?'” Delegard tells TIME. “Structural racism is really baked into the geography of this city and as a result it really permeates every institution in this city.”

Fifty years after the racial covenants were put in place in Minneapolis in the early 20th century, that kind of racism was the subject of demonstrations nationwide, as the civil rights movement fought for equal access to housing.

Mayes says the protests following George Floyd’s death can be compared to the 1967 uprising in northern Minneapolis during “the long hot summer of 1967.” While there are several theories about how that clash started, the most common involves a conflict between police officers and a neighborhood resident. “I wish I could tell you there were differences between the 1960s and today, when it comes to police incidents, but it’s the same,” says Mayes.

The Fair Housing Act of 1968 made racial covenants illegal, but other ways to maintain the neighborhood demographics emerged. Delegard cites freeway 35W, which was built in the 1960s and runs between downtown and the southern suburbs, as a modern barrier between the Old South Side and whiter, wealthier areas. Then, in 1969, police detective and political newcomer Charles Stenvig was elected mayor on the platform of “take the handcuffs off the police,” becoming one of the first so-called “law and order” mayors in the country. The already powerful police department became even more powerful.

And the effects of now-illegal racial covenants can still be seen today.

“The places on the map where we found these racial restrictions are still the whitest parts of the city today,” says Delegard. “Our research shows that there was this preoccupation with making sure the city would stay all white. The racial composition of the neighborhoods we have today was created, deliberately constructed through time. These rigid racial boundaries were enforced through courts and the police for a century in Minneapolis, and it does lead to violent encounters.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com