Katherine Massey had a list. She needed to get meat, fruit, paper towels. The 72-year-old Buffalo native usually went to the grocery store every two weeks, and when she did, she stocked up. On Saturday, May 14, she asked her brother, Warren, to drive her.

The three Massey siblings—Kat, Warren, and Barbara—all lived on the same street in Buffalo’s Fruit Belt neighborhood, a tight-knit, predominantly Black and working-class community on the city’s East Side. Warren, 66, and Barbara, 64, alternate chauffeuring their eldest sister, who no longer drives. This time, it was Warren’s turn.

“Usually, I sit in the parking lot,” he says. “But she told me to go home. She never did that before. She said, ‘Come back in 45 minutes.’”

When Warren came back, around 2:30 p.m., the parking lot of the Tops market on Jefferson Avenue was filled with police and paramedics. Blood stained the pavement. Bodies were on the ground.

The cops would not let Warren inside the store. It was an active crime scene. As he stood outside, Barbara arrived. She had been mowing Kat’s lawn for her when a neighbor ran up, frantic, to say that there had been a shooting at Tops. Barbara felt her heart tighten. She made it to the market within minutes. “There were so many police,” she recalls. “It was, like, Oh my God. Oh my God.”

She approached one officer, then another, then another, and another. “My sister’s in there,” she told them. “Can you just let me know if Katherine Massey is OK? She’s a little thing. She’s probably 110 pounds.’”

She closes her eyes now and takes a deep breath. “I must have made that same speech 20 times to 20 different officers.”

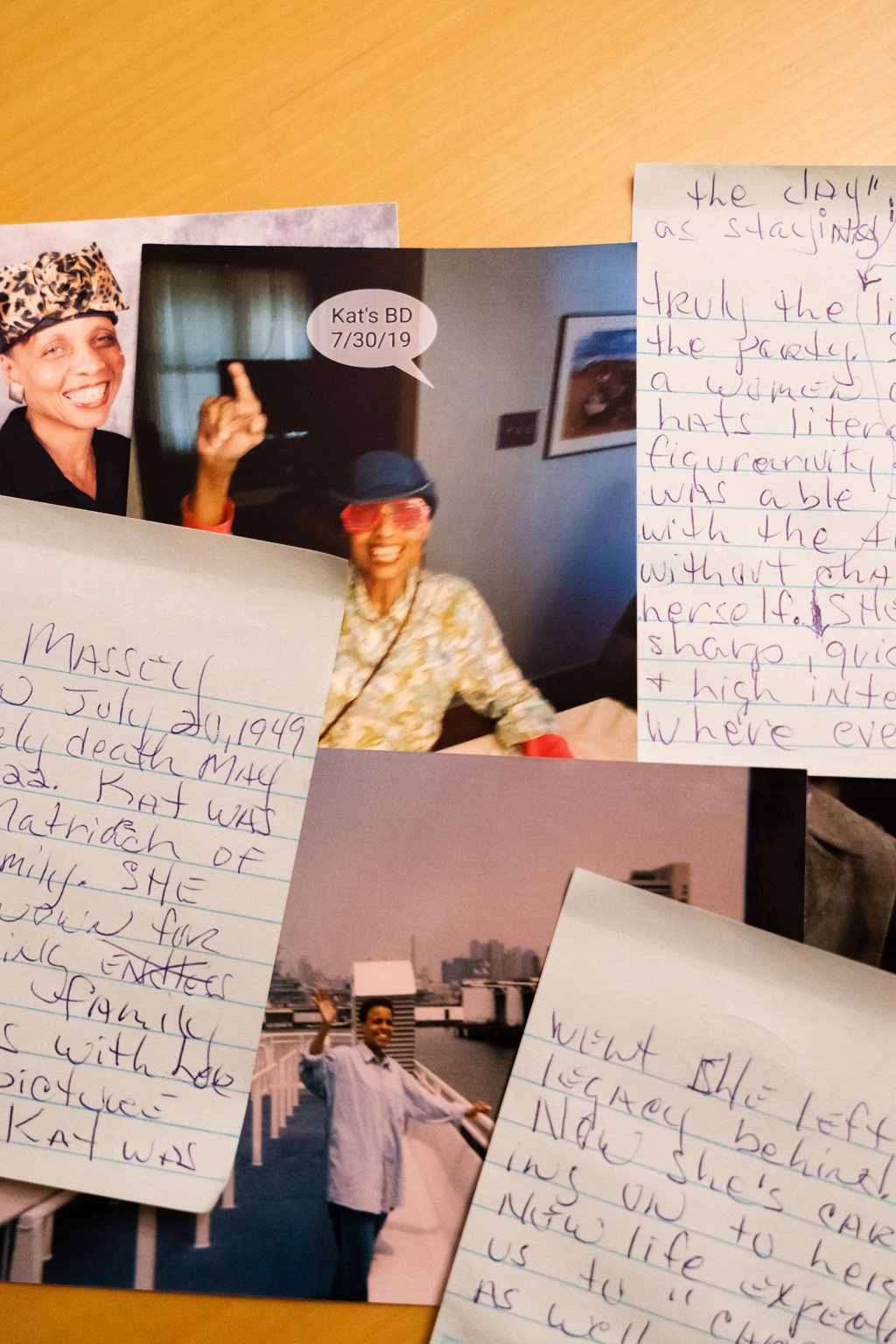

Four days after the shooting, Warren and Barbara told me about Kat, who was one of the 10 people killed by a racist gunman who picked his target because of the surrounding neighborhood’s high concentration of Black residents.

The Massey family has been living on Cherry Street in Fruit Belt for more than 60 years. We sat in Barbara’s darkened living room, with its brown leather couches, blue carpet, and plants. One flower had a “Happy Mother’s Day” balloon still attached.

Wearing pink Friends pajamas, Barbara told me about her older sister, a civic activist and outspoken voice in Buffalo for stricter gun-safety laws. Just last May, she wrote a letter to The Buffalo News calling for greater oversight over firearm sales. (The alleged assailant bought his AR-15 gun even after undergoing a psychological evaluation for allegedly threatening violence at his high school.)

According to her friends and family, Kat’s advocacy against gun violence was emblematic of her character. “She was about educating her people,” says Sharon Belton-Cottman, a close friend of the family who serves on Buffalo’s Board of Public Schools. “She was about making a difference in the lives of her community. And she was about action.”

Kat, who was single and worked as an insurer for Blue Cross Blue Shield for 40 years, often put on theatric presentations in the city’s schools to encourage healthy eating. She ran a Block Club to cut grass in Fruit Belt. She co-founded a nonprofit advocacy group for Buffalo’s inner-city residents called We Are Women Warriors. And she successfully lobbied City Hall and the Common Council in 2010 to put in a small public park off Cherry Street, where she had them enter the inscriptions of African proverbs along the sidewalk.

“Each one of these symbols represents who Kat was,” Belton-Cottman pointed out as we walked down Cherry Street. She noted one that said Sankofa. “That’s the spirit of giving back—go and retrieve wisdom, knowledge, and the people’s heritage.”

Barbara’s entreaties to the cops outside Tops went unanswered. So she and Warren stood sentry at different ends of the supermarket’s entrance. As they waited for signs of their sister, more family members showed up—seven in all.

Soon, authorities confirmed that the gunman had killed 10 people and wounded three others in the rampage. But officials could not yet identify the victims.

As Warren finally watched police escort survivors out of the building, he had a feeling in his gut. “I knew she was dead,” he says. “When they marched them all out, I was at the side of the building. She wasn’t there. It was over.”

The family waited on the pavement outside the store until it got dark and an FBI special agent told the assembled crowd that authorities wouldn’t have any updates for many more hours. So Barbara and Warren went home. Barbara took a shower and prayed that she could fall asleep, but she couldn’t.

Some of their children stayed. In the morning, Barbara heard from her nephew, who had watched the police remove body bags from Tops around 4 a.m.

“But nobody called us,” Barbara says. “Nothing. So I’m getting a little pissed.”

She called 9-1-1 and told the operator that she was the sister of Katherine Massey, who was in Tops at the time of the shooting. The operator told her to visit the Buffalo Police Department’s website, to get the number of the coroner.

When Barbara got her on the phone, the coroner asked questions about what Kat looked like.

Barbara ticked off her identifying features: Blue eyes. Blue clothes. Black skin. Brown scarf. “She’s got rheumatoid arthritis,” Barbara added. “Just look at her hands.” The coroner promised to call back in 20 minutes.

“She called me back crying,” Barbara says. “The coroner was crying. A coroner.”

“I’m sorry,” the coroner said. “I’ve got your sister.”

The day after the shooting, Warren and Barbara gathered with their extended family, vacillating between rage, despair, and crippling guilt, obsessing over the little twists of fate that could have been the difference between life and death.

“I just wish it was my turn taking her,” Barbara says, “because we go to the Tops on Elmwood. But she didn’t ask me. She asked Warren.”

“At first, I was blaming myself,” Warren says. “But [my family] made clear it wasn’t me.”

Barbara, a soft-spoken woman, couldn’t stop thinking about the shooter. “I wanted to choke him out. I wanted him to die,” she says. “I know that’s not where I was supposed to be, but that’s where I was at.”

New York State does not have the death penalty, and as the days passed, Barbara began to take comfort in that, feeling that it would be a harder punishment for the shooter to have to sit all by himself in a small cell for the rest of his life.

“We know he’s going to get life,” she says. “Eighteen-year-old piss pot. Still so young he’s got mucus on his breath. I just don’t want him to commit suicide. That’s the coward’s way out. I want him to sit there and hopefully think about the consequences—how many lives he ruined.”

Barbara has had trouble falling asleep since Saturday. She keeps replaying the massacre in her head. At the same time, she’s caught between the competing demands of grieving her sister and making arrangements—for the obituary, the wake, the funeral, the burial. There will also be a ceremony to designate the street where the family lives as “Katherine Massey Way.”

The obituary was the easiest part: Kat had already written it herself in 2012, along with a last will and testament. The letter she wrote to the family about her wishes “was all uplifting,” Barbara says. “She put in there, ‘Barbara, don’t be a wimp. You got this.’”

When I met with Warren and Barbara on Wednesday, it was hours before the coroner was set to release the bodies. Warren felt the need to see his sister’s, even though he was aware it would be grisly.

“He shot her head off,” Warren says. “So until I see her fingers, I’m gonna say that ain’t her. But I know it’s her.” (The coroner was able to identify Kat by her clothing and arthritic fingers.)

The funeral will be Monday at the Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church, a stone’s throw away from Kat’s house. Until then, Warren and Barbara are hoping that Kat’s obituary of her life—and not her death—will define how she’s remembered. They want people to read it and feel like they knew her personally.

“If you met Kat, you couldn’t forget her,” Barbara says. “I’ll tell you that.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com