For those of us who weren’t around to remember what it was like before the Supreme Court upheld Americans’ right to safe, legal abortion, the imagery we associate with the pre-Roe-v.-Wade era is cartoonish. Back alleys. Coat hangers. Maybe that’s easier than registering the real, human misery of places like Cook County Hospital’s septic abortion ward, where doctors prohibited from performing abortions scrambled to save women who experienced life-threatening complications after procuring them illegally. In the excellent documentary The Janes, Dr. Alan Weiland, an OB-GYN who worked at the Chicago hospital as a medical student, recalls that “the septic abortion ward was full every day.”

The Janes, airing on HBO and streaming on HBO Max June 8, is not mostly a catalog of the suffering pregnant people endured before Roe became the law of the land and septic abortion wards became a relic of a barbaric past. It’s a story of everyday heroism. Directors Tia Lessin (Trouble the Water) and Emma Pildes (Jane Fonda in Five Acts) take a sensitive, close-up look at Jane, a collective of women who banded together in late-1960s Chicago to provide safer, discreet, affordable abortions to thousands of desperate patients. The timeliness of the film, which arrives the same month that the Supreme Court is expected to overturn Roe, is crushing. But it’s also crucial—and not just for activists in search of a practical playbook. With many states poised to outlaw abortion as soon as this summer, every American needs to understand what drove the Janes to take action.

Sign up for More to the Story, TIME’s weekly entertainment newsletter, to get the context you need for the pop culture you love.

Because legally protected reproductive rights are generally exercised behind closed doors in spaces subject to HIPAA regulations, personal narratives, sometimes volunteered at great risk to the speaker, have always been crucial to the abortion debate. So it makes sense that they are also the core of The Janes. Free of any manipulative voice-over narration, cutesy animated infographics or celebrity-feminist testimonials, the film centers the experiences, between 1968 and 1973, of people who never became household names. And that’s more than enough.

The stories Lessin and Pildes unearth of the Chicagoland abortion underground are as instructive as they are harrowing. The Janes opens with one woman’s first-person account of an ordeal in which a mobster demanded that she choose between a Chevrolet, a Cadillac, or a Rolls Royce—three different price points for three different illegal-abortion experiences. Young and broke at the time, she opted for the Chevy and endured a procedure performed quickly and sloppily in a seedy motel room, alongside a second patient. “They spoke all of three sentences to me the entire time,” she recalls. “‘Where’s the money?’ ‘Lie back and do as I tell you.’ ‘Get in the bathroom.’ That was it.” When it was over, the two strangers were left alone together, bleeding, without any information on how to care for themselves as they recovered.

Motivated by empathy rather than money—the Chevrolet cost $500 in the ’60s, or the equivalent of $4,000 today—the founders of Jane resolved to do better. They were, with a few notable exceptions, young, college-educated, middle-class white women who’d come up in the male-dominated antiwar and civil rights movements. (Without undermining what their subjects were able to accomplish, the filmmakers incorporate several participants’ apparently sincere expressions of regret over the fact that Jane was much whiter, as an organization, than the communities it served.) Many had their own horrific abortion stories to tell. And they devised smart ways of improving upon those experiences, from periodic check-ins with patients for two weeks after the procedure to two-part appointments that entailed ferrying them by car from a waiting room known as the Front to a makeshift operating room (the Place) in a second location.

When they realized that an abortion provider they’d pressured into treating women who often couldn’t pay much, if anything, wasn’t actually a doctor, he agreed to teach the Janes what he knew. (Lessin and Pildes tracked down this construction worker turned unwitting feminist ally for an interview. “It was a job,” he shrugs. The women remember him as a hustler, but he did the work carefully and, unlike many other guys in his position, treated patients kindly.) Along with saving money, this empowered the Janes to take reproductive healthcare into their own scalpel-wielding hands. From a contemporary perspective, at a time when the pro-choice movement talks a lot about the sanctity of a patient’s relationship with their doctor, it’s intriguing to hear these activists speak of their desire to liberate women not just from draconian laws or predatory underground abortion providers, but also from a patriarchal medical establishment. They might have felt differently if the male doctors they reached out to for help, many of whom were actually referring patients to Jane for abortions, hadn’t routinely told them to get lost.

Of course, 2022 is not 1968. Obstetrics and gynecology is no longer a male-dominated field; in recent years, more than 80% of OB-GYN residents have been women. Meanwhile, the advent of medication abortion, and an existing infrastructure of organizations aimed at getting these pills to patients who don’t have easy access to them or funding out-of-state travel in cases where surgery is still required, means that bloody-hotel-room—let alone back-alley—scenarios will almost certainly be rarer post-Roe than they were in Jane’s day. There are laws, though not infallible ones, to counteract the employment discrimination pregnant women faced at the time. And The Janes doesn’t strain to make the argument that the future will look identical to the past.

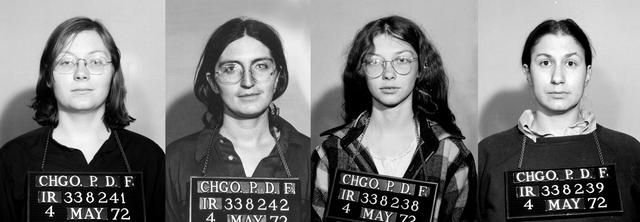

Instead, the film stays focused on the specific story it’s telling, trusting viewers to spot potential parallels and glean relevant lessons. We watch opportunists profit from abortion bans, just as they profited from bootlegging during Prohibition. When New York legalizes abortion, in 1970, we see wealthy, often white women start flying out to have the surgery done there; in Chicago, poor women, who are largely women of color, come to predominate among Jane’s clientele. A homicide squad staffed by men with little to say, either way, about abortion is ultimately brought in to apprehend the Janes.

Beyond the obvious certainty that people will die if Roe is struck down, the film illuminates how that decision is likely to exacerbate all manner of other social ills—racism, over-policing, profiteering by way of black-market medicine. Through individual interviews, a composite image forms of a society touched on every level by half its population’s lack of bodily autonomy. If that’s the country we’re about to live in, then we owe it ourselves to go into it with open eyes.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com